Abstract

Research Question

Did gang members and gangs named by police in four separate court-ordered 24-month injunctions, issued at different times, reduce the frequency and harm of crimes they committed, and suffer fewer crimes against themselves as well?

Data

The study examined criminal histories of 36 members of four gangs for a 36-month period before and a 36-month period after their respective injunctions. Data also included records of crimes committed against the gang members in the same time periods. Criminal activity was measured by arrests, station interviews, fixed penalty notices and summonses. Days offenders spent in custody, which rose during the gang injunction periods, were removed from denominators calculating rates, so that the estimates of changes in offender behaviour and victimisations are all based on their days at liberty and out of prison or jail.

Methods

The study compared the magnitude of change in both individual-level and gang-level measures of crime and victimisation from before to after the issuance of the injunction as ‘natural quasi-experiments’, with comparisons made to other gangs in Liverpool which had not been subjects of injunctions.

Findings

Across all 36 gang members, their individual offending counts dropped by 70% in the 3 years after their gang injunctions, while the Cambridge Crime Harm Index weight of the seriousness of their total crimes dropped by 61%. Fewer criminal events were attributed to 92% of the individuals in the second 3-year period than in the first, while only 8% increased their detected activity. Taking the four gangs as the unit of analysis, their offences dropped by 74% in the 3 years after the injunctions, while their Crime Harm Index weight dropped by 70%. Victimisation of the gang members in their 3-year post-injunction period dropped by 60% compared to the pre-injunction period. Comparisons between gangs with injunctions and gangs without showed downward crime trends in the injunction gangs that were not observed in the comparisons during the same time periods, but regression to the mean could not be ruled out as an explanation for the findings.

Conclusions

The evidence for the effectiveness of gang injunctions in reducing crime harm is stronger than the evidence for most police practices. There is no evidence in this study of these injunctions causing crime to increase. Police agencies may be encouraged to use such powers when available, as long as they track the trends with sufficient care to detect any potential backfire effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Young men in gangs challenge police forces around the world. While the range of legal powers to meet that challenge varies widely, few of those powers have ever been evaluated for their effectiveness. In 2009, the government of England and Wales introduced a tool aimed at preventing gang violence: the gang injunction. The aim of this study is to assess the impact of this tool on four organised crime groups in Merseyside, to the extent possible using observational data. Examining injunctions against four gangs as ‘natural quasi-experiments’ involving 36 individuals affiliated to 4 Organised Crime Groups in Merseyside between 2009 and 2016, the study shows a consistent reduction in criminal events, the total severity of harm (as measured by the Cambridge Crime Harm Index or CHI) and victimisation of the gang members named in the injunctions.

The Gang Injunction As A Sanction Threat

Gang injunctions are designed to work by creating a ‘Sword of Damocles’ threat of punishment (Sherman 2011) to hang over the heads of named gang members, upon the basis of a court order. The Policing and Crime Act 2009 authorises law enforcement agencies to apply to a County Court for an injunction if they can demonstrate evidence showing a balance of probability that

-

an individual is involved in or has encouraged gang-related violence or drug dealing activity, and

-

a gang injunction is necessary to prevent such activity or protect the individual from harm.

In the event these conditions are met, the court may grant an injunction for a period of 2 years that would restrict movement, association with co-offenders, and other ordinarily legal activities for the named gang members. The stated purpose of these restrictions is to reduce opportunities for the persons named in the injunction to cause harm, or to be exposed to harm. Any breach, such as contact with other gang members, carries a maximum sentence of 2 years of imprisonment (HM Government 2015a, b)—a Sword of Damocles of the kind that Dunford (1990) demonstrated experimentally had reduced injuries to domestic abuse victims by simply issuing warrants for the arrest of their unapprehended offenders.

The use of gang injunctions also conforms to the concept of ‘Pulling Levers’, a process described by Braga and Weisburd (2012) as a framework of focussed deterrence strategies directed towards a particular crime problem, generally in the form of a multi-agency response, which uses a standing threat of a variety of sanctions (Pulling Levers) to press offenders to change their behaviour. A key element of this concept is direct and repeated communication with offenders to ensure they understand why they are receiving special attention. This process starts with telling the gang members that they have been named by a gang injunction, presenting the message that ‘We know who you are, where you live and what you do. If you keep doing it, we will arrest you for it’ (Decker 2003: 290).

Gang injunctions are also conceptually related to police crackdowns (Sherman 1990) as they involve a sudden increase in officer presence, sanctions and threats of apprehension for either specific offences or for all offences within a defined geographical area. Enforcement of gang injunctions, however, should in principle result in little or no inconvenience to the wider community since these gang crackdowns are directed towards specific individuals to identify any breach at the earliest opportunity.

Previous Research on Gang Injunctions

While gang injunctions are a new concept to the UK, they appear to have been used in the USA as early as 1980 (Decker 2003). Nonetheless, there is little research into the effectiveness of gang injunctions. Decker (2003) cites three studies into the impact of gang injunctions, with widely differing results:

-

An examination of crime data for Inglewood, Los Angeles, demonstrated negligible reductions in crime post issuance of the injunction (Maxson and Allen 1997).

-

Grogger (2002) examination of 14 Los Angeles County injunctions between 1993 and 1998 demonstrated modest reductions in crime after issuance of the injunctions.

-

Research conducted by the ACLU Foundation for Southern California (1997) into the effectiveness of the Blythe Street gang injunction found that there were significant increases in violent crime and drug trafficking after issuance of the injunction.

Gang Injunctions in Merseyside

The 2009 legislation dictates that, in order to obtain a Gang Injunction, law enforcement agencies must not only demonstrate that an individual has been concerned in drug dealing activity or violence. Police must also show that the persons named committed actions that were ‘gang related’. The legal requirements for how law enforcement agencies must demonstrate the ‘gang related’ character of actions is to show that

-

named persons have acted as part of a group of three or more and

-

have shown ‘one or more’ characteristic that allows its members to be identified as a group.

While this is a difficult concept to prove, the principles of Organised Crime Group Mapping (OCGM) offer a clear method for the identification of criminal groups and how they impact on communities. OCGM uses intelligence, arrest or offending histories and records of criminal convictions to ‘map’ or ‘index’ OCGs with regards to their level of intent and capability to cause harm. According to the manual on OCGM (2010), the ‘map’ or ‘index’ creates a consolidated picture in terms of where organised crime occurs, which groups are involved, where they operate and where they live.

Merseyside has an estimated population of 1.379 million, housing 190 Organised Crime Groups (OCGs) with 2883 members, all of whom have all been assessed in accordance with the principles of OCGM. The OCGs represent less than 0.01% of the population, and could be described as part of a ‘Power Few’ of most serious violent offenders (Sherman 2007).

Three Research Questions

This research is intended to answer three research questions about the changes associated with the issuance of injunctions against four gangs in Merseyside, a policing area that includes the City of Liverpool. Each question focuses on the gang members named in four separate injunctions, issued at different times, in relation to criminal events in which they were named in police investigations during the 24-month period of the injunction:

-

1.

Did violent crime by gang members decline?

-

2.

Did the total Cambridge Crime Harm Index value of the crime by gang members decline?

-

3.

Did criminal victimisation of the gang members decline?

Data

Data for this article includes the offending histories of 36 individuals between 2009 and 2016, all of whom were affiliated to four Organised Crime Groups (OCGs) in Merseyside and named in a court order called a gang injunction. These data contain data on specific offence types that can be coded by the Cambridge Crime Harm Index (Sherman et al. 2016), a tool to measure severity of harm from criminal events based on Sentencing Guidelines for each offence type in England and Wales. The CHI is a weighted index that assigns more weight or significance to more serious crimes than to less serious crimes.

Methods

Since April 2012, Merseyside Police have named a total of 75 individuals in gang injunctions against 9 different OCGs situated in different areas across the Merseyside area. In each case, hierarchical structures have been determined, intelligence assessments made and applications in respect of gang members have been granted by the Liverpool County Court. Most of injunctions are relatively recent and do not provide sufficient longevity to allow feasible assessment against the research questions, and others did not translate into ‘full’ injunctions because some individuals had been sentenced to substantial periods of imprisonment post issuance of an ‘interim’ injunction. The study is therefore limited to injunctions against the four gangs that offered follow-up periods of 36 months.

At the time this study was undertaken as a master’s thesis in the Cambridge Police Executive programme, there were 36 individuals affiliated to 4 OCGs who had been subject to gang injunctions for significant periods. They presented an opportunity to assess whether the injunction had made a difference in terms of offending volume, associated harm and victimisation. Having been subject to four separate gang injunctions (in April, July and October 2012 and March 2013 respectively), they presented an opportunity to examine their longitudinal offending history for 36 months ‘before and after’ the injunction. It is those 36 subjects of four gangs subjected to injunction who comprise the core of the ‘natural quasi-experiments’ in this study (see Table 1).

It is important to note that gang injunctions are personalised to the individual and while ‘interim’ injunctions may be granted in one hearing, applications with regards to ‘full’ injunctions can be heard and granted at different times. As a consequence, duration of injunctions may vary across individuals in the data set. This research established that injunctions subject of this study were granted for periods ranging between 25 and 36 months. To analyse the cumulative effect of gang injunctions, the first author calculated the average duration of each injunction in the study as 31 months, thereby allowing greater consistency with regards to a cumulative analytical assessment across all four gang injunctions.

Measuring Offending

This study measures offending by these 36 offenders on the basis of arrests, rather than charges or convictions. While this measure is not perfect, it is more inclusive than the alternatives. The Serious and Organised Crime and Police Act of 2005 requires that the lawful arrest of an individual be supported by two elements of evidence: (1) a person’s involvement, suspected involvement or attempted involvement in the commission of a criminal offence; and (2) reasonable grounds for believing that the person’s arrest is necessary in that regard. These fundamentals were deemed insufficient, however, in 2012 by a revision of Code G of the Codes of Practice; this was revised to reflect the requirement to place greater emphasis on the use of a process known as ‘Voluntary Attendance for Interview’ as a viable alternative to arrest. This revision falls within the period of this research and therefore ‘Voluntary Attendance’ is considered an equally strong indicator of offending behaviour as arrest. Finally, English law counts as sanctions police actions called ‘fixed penalty notices’ and ‘reporting of the facts for summons’. These may be less intrusive options for offender management but are also equal to arrest as indicators of offending behaviour.

In summary, offending behaviour by the 36 subjects of this study is measured consistently from before to after the gang injunction by (1) arrests, (2) voluntary attendance for interviews, (3) fixed penalty notices and (4) summonses. These measures are derived from enforcement activity, so there is a possibility that there is a bias based on extra police attention to persons named in the gang injunctions. That bias, however, would only tend to under-estimate any crime reduction effects, since it would detect more crime among those named by injunctions than among those in the comparison groups.

Data Sources

In order to gather the necessary information with regards to ‘first-stage’ offending behaviour, this study examined records held on a Merseyside Police information technology system known as Niche RMS (Records Management System), which is a single unified operational policing system that captures the complete ‘Merseyside Specific’ history of people, places, vehicles, property and evidence. While this system provided the majority of data for this study, additional data contained within the Police National Computer (PNC) and the Police National Database (PND) was examined in order to ensure that the complete national offending picture is considered for each of the 36 subjects as well.

Niche

This system is commonly used across law enforcement agencies in England and Wales, and while there are a number of functions, this research will focus on data held in respect of offender management, such as custody records, crime classifications and modus operandi. Every incident or event relating to crime and offending is recorded on Niche RMS as an ‘Occurrence’, each of which are identified through a unique ten-digit reference number to which all aggrieved, offenders, suspects, witnesses, vehicles and places are linked. It is important to note that Niche relies heavily on human input and as a consequence is susceptible to human error and in some cases duplication of records. While over time the potential for duplication has been reduced, fixed and free text fields containing personal information as well as official crime and offending data were examined with rigour in order to ensure accuracy and avoidance of ‘double counting’.

Police National Computer

The Police National Computer (PNC) is a national database of offence, conviction, bail and confinement records and has been described as the ‘backbone’ of studies that seek to establish whether an individual has been arrested or convicted in the UK (Sutherland 2013). With the allocation of a unique identification number known as the PNCID, which is linked to other unique verifiable reference numbers and undergoes constant accuracy scanning and cleaning at the local and national levels, there can be a fairly high degree of certainty placed on the reliability of data derived from the PNC.

PNC records of the 36 individuals associated with this study have been physically examined in order to establish a complete list of all four of the ‘first-stage’ offending indications of offending. Dates of arrest, or in cases of summary convictions and fixed penalties the date of offence, have been extracted in accordance with the time parameters of this study.

Time at Liberty

The individual subjects of this study are considered high-frequency, high-harm offenders, and as such, it is not unusual they spend periods of time in custody. Records contained within the Police National Computer demonstrate that this cohort spent on average 6% of their time in custody before the gang injunction and on average 14% of their time in custody afterwards. This study therefore adjusts offending rates to allow for time ‘at liberty’ as failure to adjust for time spent in custody may lead to an under-estimation of reoffending and a corresponding over-estimation in terms of rate of desistence, by virtue of having over-estimated exposure time to offending (Ferante et al. 2009). The PNC holds the relevant remand, bail and custody information, which allows for a month-by-month assessment of remand and custody and a high degree of certainty with regards to the identification of time at liberty.

Data Compilation

Initial acquisition of all material relevant to this study was undertaken by a Merseyside Police Analyst, who was experienced in extracting data of this type. All formatting, examination and analysis of this data was completed by the first author. Further details on data extraction, categorisation and limitations are available at Carr (2016).

Measurement of Harm

The instrument used for measuring severity of harm in the analysis of these questions is the Cambridge Crime Harm Index (CHI). To achieve consistency of measurement, the author manually indexed appropriate CHI values to each of the 636 offending and victimisation records. Harm values have been determined in accordance with the work of Sherman et al. (2016), which creates a consistent and robust measurement of crime harm. There are however a number of factors within this study which make it necessary to introduce an element of subjectivity to the concept of harm. First, a number of offences contained within the data, such as cruelty to animals and breach of the peace, do not carry an associated harm score and therefore the author has introduced a CHI value of 1 to ensure offence records of this nature are included in the overall mean harm values. Second, offences described in accordance with Home Office Counting Codes 149/00/01 and 149/00/03 as criminal damage to a dwelling or vehicle with a value under £5000, which carry a CHI value of 2, do not adequately reflect the seriousness of the offence when the damage had been caused through the discharge of a firearm. Therefore, a more reflective CHI value of 1825, associated with the possession of a firearm with intent to cause fear of violence (Home Office Code 008/23), has been applied in these circumstances.

Analytic Procedure

This study seeks to address the research question at both the individual and gang levels:

-

1.

Whether there is a difference in offending rates, levels of harm and victimisation associated with individual gang members immediately following the issuance of a gang injunction

-

2.

Whether there is a difference in offending rates, levels of harm and victimisation associated with the gang as a whole immediately following the issuance of a gang injunction

Individual and gang averages in terms of offending and associated harm were calculated in accordance with time ‘at liberty’.

Findings

Individual Offending Volume

The cleaned dataset contained 485 offending episodes, distributed over 36 individuals. These events were divided into before and after the date of each subject’s injunction. Because there was an increase of days spent in custody in the after periods, all findings are adjusted for subject days ‘at liberty’ and out of custody as the denominator for rates calculated.

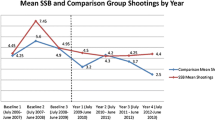

Figure 1 below displays a longitudinal analysis of ‘at liberty’ offending behaviour of OCGs 1–4 across 36 months before and after the injunction. It demonstrates how in the period before the injunction, this cohort were each associated with an adjusted average of 0.317 offences per month (OPM) spent at liberty, while in contrast in the period after the injunctions, the same offenders were involved in an average of 0.095 OPM at liberty, representing a difference of -70%. Further analysis of individual offending data illustrates how although 8% of individuals increased their offending rate during the period beyond the injunction, the remaining 92% demonstrated reduced levels of offending, with some falling to zero across the examination period.

Individual ‘At Liberty’ Crime Harm Values

Average harm values were calculated with regards to the longitudinal study, and similarly ‘adjusted’ averages were calculated in respect of the reduced examination period.

Figure 2 below illustrates the difference in harm associated with ‘at liberty’ offending for OCGs 1–4 across the longitudinal study. Analysis shows that during the period before the injunction, this cohort each caused an average of 112.75 units of CHI harm per month, whereas in the period beyond, they caused an average of 44.14 CHI per month, a difference of -61%.

Group Offending Analysis

Analysis of data thus far has concentrated on overall and individual offending, associated crime harm and victimisation ‘before and after’ the gang injunction. While these results tell part of the story, they do not specifically address the question in terms of whether or not these differences are induced as a consequence of a gang injunction. In order to add a stronger basis for inferring causation, the analysis also makes a series of comparisons to other gangs in time periods when they had not been subjected to injunctions.

‘At Liberty’ Offending and Harm Associated with OCGs 1–4 Across 36 months ‘Before and After’ the Gang Injunction

Figure 3 below displays the monthly volume of total offences per at-liberty gang member in OCG1, showing a pattern similar to the other three OCGs (for full display of figures for each OCG, see Carr 2016). The pattern is similar to that in Fig. 4, which displays Crime Harm per member at liberty for OCG1. All trends are shown in Fig. 7.

Both Figs. 3 and 4 show a similar pattern as the data displayed in Table 2.

Table 2 displays baseline differences, but proportional similarities in post-injunction changes in offending and associated harm attributed to OCGs 1–4. In four out of four cases, there are similar reductions in both crime volume and crime harm, with greater proportional reductions in OCGs 2 and 4 which had the highest baseline offending volume.

When the four natural quasi-experiments are combined in a pooled analysis standardised by the date of their respective injunctions, they show the same clear pattern of decline in volume of offending, with a slight rise after the expiry of the injunctions (Fig. 5). Figure 6 shows a similar pattern with the pooled analysis of Crime Harm Index values per members at liberty.

Using Staggered Dates of Injunctions to Create Comparison Groups

In Fig. 7, the offending frequency trends for all four groups are presented in real time to provide a series of comparisons between OCGs with and without injunctions. The analysis of OCG1 as the first treatment group, for example, illustrates that after the injunction there is an obvious decline to the point of expiry, when there is evidence of decay in deterrence as offending begins to rise. At the same time, OCG2 served as the first comparison group to the OCG1 trend until OCG2 received its own injunction. In this contrast, while group 1 was declining after the injunction, group 2 demonstrated an escalating trend until the issuance of its injunction. This shows that when group 1 started its decline, there was no general (or what methodologists call ‘secular’) decline in gang crime, at least among these four gangs in Merseyside. Similarly, analysis of OCG3 as the second comparison group illustrates a marginally static offending pattern while OCG1 was declining, until the introduction of group 3’s injunction at which point offending declines in a similar way.

The most pronounced effect is observed with OCG4 as the final comparison group, in relation to all three groups that received injunctions before OCG4’s. While all other OCGs are subject to treatment with their offending in decline, offending with regards to OCG4 continues to escalate until the injunction when treatment takes effect and offending declines in a sharp downward trajectory.

In the same way Fig. 7 illustrates the difference between treatment and comparison groups for offending volume, Fig. 8 illustrates a similar picture with regards to harm. Again, analysis of OCG1 as the first treatment group shows associated harm declining beyond the point of injunction until expiry when decay begins to take effect. When compared against OCGs2 and 3 as the first control groups, while it is difficult to detect any discernible short-term difference, beyond the injunction these groups follow a similar pattern as displayed by OCG 1. Again, the most pronounced difference occurs with OCG4, which while OCGs 1, 2 and 3 are receiving treatment and demonstrating a downward trajectory with regards to harm, OCG4 as the final control group, while receiving no treatment, harm continues to escalate sharply until the point of treatment when it declines almost to the point of zero.

Other Trends

Carr (2016) presents further details regarding enforcement of breaches of gang injunctions, victimisation of the gang members and comparisons across two other OCGS that received injunctions very recently (and lacked a full 36 months of follow-up observations). The main points of these further analyses are as follows:

-

1.

Most breaches of the gang injunctions occur in the first year, with few if any breaches in year 2.

-

2.

Victimisation of gang members (as victims of crime) declined by 60% after the injunctions, with no victim of serious violence before the injunction sustained a new serious incident after the injunctions.

Conclusions

The answers to the three research questions, for both gang members and gangs as groups, are all ‘yes’. Relative to the 36 months before the injunctions were imposed on each of the four OCGs, violent crime by gang members declined, the Crime Harm Index value of the crime they committed declined and criminal victimisation of the gang members declined. Since these patterns are remarkably consistent, they raise the most important question about the policy implications of these findings: did the gang injunctions cause these changes from before to after? In other words, were the reductions in offending and victimisation the impact of the injunctions, did they all occur by chance or were they all caused by some other factor?

The answer to the question of causation is always elusive. By using each OCG as the comparison group for all of the others, we can eliminate the rival hypothesis that the cause of the reductions was a general decline in gang violence, or crime in general. The data clearly show that while one OCG shows a drop in crime after its injunction, other OCGs at exactly the same time are continuing or increasing their crime rates and harms. That means we have controlled for what impact evaluation methodologists like Donald T. Campbell call ‘history’ (Cook and Campbell 1979).

What this analysis cannot control for is ‘regression to the mean’, or the natural tendency in any statistical series for what goes up to come back down. That kind of ‘noise’ is normal fluctuation in any series of events, such as football teams winning or losing many games in a season. The large rise and fall of crime by OCG4 before it rose again until a gang injunction was imposed may be just such a pattern of internal growth and decline in crime. While it seems unlikely that all four separate OCGs would have a ‘change’ regression to the mean at almost exactly the moment that an injunction is issued, and in very similar magnitudes, it is impossible to rule that out with just four cases.

What may be more important, however, is the lack of any backfiring effect. Unlike the case cited in the USA (ACLU), none of the Merseyside cases showed any increases in crime volume or harm, let alone victimisation of the gang members. On this point, the data are consistent for all four groups with the 36 offenders in the overall data set. While a small percentage of the offenders named in the injunctions (8%) increased their offending after the injunction, the vast majority (92%) reduced their offending. On that basis, the worst that can be said about these findings is that there is a small possibility that they may reflect no true benefit; there is no evidence of a possible causation of harm.

These findings therefore serve to offer law enforcement agencies across England and Wales the opportunity to use Gang Injunctions to tackle gang-related criminality in an alternative way from traditional crime-by-crime enforcement.

Policy Implications

Successive government policy has witnessed an escalation of civil orders and injunctions designed to protect communities from harm. The introduction of gang injunctions, however, saw a shift in emphasis within a legislative framework that not only sought to protect communities but also to protect the enjoined individuals themselves from harm. Some groups challenged their introduction as having a disproportionate impact on already disadvantaged communities (Liberty 2010). The present research goes beyond prior studies by isolating changes in offending behaviour to the temporal point of intervention and using treatment versus multiple control analysis to eliminate some of the other possible explanatory factors for change. More important, when results were examined with regards to victimisation of the gang members, similar findings were observed. The key component of this policy designed to protect the individuals from harm may have been successfully delivered, and certainly no increase in harm to gang members was observed.

Finally, while the scope of research did not include ‘cost-benefit’ analysis, Merseyside Police estimate the cost of injunctions for each OCG to be in the region of £15,000.00. When compared against investigative costs for serious and complex crimes, they demonstrate excellent value for money.

In summary, this study provides four tests of the hypothesis that gang injunctions work. Three of these tests had a comparison group. All four showed a change in the desired direction on six measures, for 24 out of 24 tests. Compared to the complete absence of evidence for most innovations in policing, the evidence supporting gang injunctions would appear to be strong indeed.

References

Braga, A., & Weisburd, D. (2012). The effects of'pulling levers' focused deterrence strategies on crime. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2012:6.

Carr, R. (2016). Gang injunctions and violent crime in Merseyside: an exploratory analysis. Thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the Master’s Degree in Applied Criminology and Police Management, Cambridge Police Executive Programme, Institute of Criminology, University of Cambridge.

Cook, T. D, & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi experimentation design and analysis for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally

Decker, C. H. (2003). For the sake of the neighbourhood: civil gang injunctions as a gang intervention tool in South California. In C. L. Maxson, K. Hennigan, & D. C. Sloane (Eds.), Policing gangs and youth justice (pp. 239–261). England: Thompson Wordsworth.

Dunford, F. W. (1990). System-initiated warrants for suspects of misdemeanor domestic assault: a pilot study. Justice Q, 7(4), 631–653.

Ferante, A., et al. (2009). Assessing the impact of time spent in custody and mortality on the estimation of recidivism. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 21(2), 273–287.

Grogger, J. (2002). The effects of civil gang injunctions on reported violent crime: Evidence from Los Angeles County. The Journal of Law and Economics, 45(1), 69–90.

Her Majesty’s Government (2015a). Injunctions to prevent gang-related violence and gang-related drug dealing: a practitioners guide’. Retrieved 12th April 2016 from https://www.gov.uk.

Her Majesty’s Government (2015b) Serious crime act 2015, fact sheet: ‘gang injunctions’. Available from https://www.gov.uk. Accessed 13 Apr 2016.

Liberty (2010). ASBOs and civil orders. Retrieved 3rd September 2016 from https://www.liberty-human-rights.org.uk/human-rights/justice-and-fair-trials/asbos-and-civil-orders.

Maxson, C. L., & Allen, T. L. (1997). An evaluation of the city of Inglewood’s youth firearms violence initiative. Los Angeles: Social Science Research Institute, University of Southern California.

Organised Crime Partnership Board. (2010). Organised crime group mapping manual. London: National Coordinators Office (NCO).

Sherman, L. W. (1990). Police crackdown: initial and residual deterrence. Crime and Justice, 12, 1–49 Electronic.

Sherman, L. W. (2007). The power few: experimental criminology and the reduction of harm. J Exp Criminol, 3(4), 299–321.

Sherman, L. W. (2011). Al Capone, the sword of Damocles and the police-corrections budget ratio. Criminology & Public Policy, 10(1), 195–206.

Sherman, L., Neyroud, P. W., & Neyroud, E. (2016). The Cambridge Crime Harm Index: measuring total harm from crime based on sentencing guidelines. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 10(3), 171–183.

Sutherland, A. (2013). A methodology for reconviction studies using Police National Computer (PNC) data. Unpublished.

Wellford, C. F., & Wiatrowksi, M. (1975). On the measurement of delinquency. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 66(2), 175–188.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the College of Policing and its Police Knowledge Fund for supporting this research with half of the cost of a partnership project between Merseyside Police and the University of Cambridge Police Executive Programme. The authors also thank the Merseyside Police for supporting the first author in pursuing his master’s degree in applied criminology and police management at the University of Cambridge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Carr, R., Slothower, M. & Parkinson, J. Do Gang Injunctions Reduce Violent Crime? Four Tests in Merseyside, UK. Camb J Evid Based Polic 1, 195–210 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-017-0015-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-017-0015-x