Abstract

Group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for adolescent depression, but outcomes vary. Our goal was to examine interpersonal factors that predict response to group CBT for adolescent depression using a broad range of outcomes, including depressive symptoms, session attendance, treatment completion, engagement, and improvement. Seventy adolescents (age 14–18) with depression completed self-report measures of social support and parental conflict and were offered an established 16-session group CBT program. Correlation and regression analyses were conducted for interpersonal predictors and CBT outcomes. Accounting for pre-treatment depressive symptoms, fewer social supports predicted lower likelihood of finishing treatment and less clinician-rated improvement. Greater pre-treatment parental conflict predicted fewer sessions attended, lower clinician-rated engagement, and less clinician-rated improvement. Results highlight the need to consider interpersonal difficulties in CBT, as they may present a barrier to treatment attendance, engagement, and improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a prevalent disorder and a leading cause of disability worldwide (Ferrari et al., 2013; Mathers et al., 2008). Beginning around 14 years old, rates of depression increase dramatically (Hankin et al., 1998), with an estimated 25% of youth experience a depressive episode by young adulthood (Kessler et al., 2001). Adolescence is also characterized by socioemotional changes, including increases in intensity of parental conflicts and in the salience of relationships with peers (De Goede et al., 2009; Lam et al., 2014). Given that adolescence is marked by increasing rates of depression and changes in relationships, it is important to consider the role of interpersonal factors in adolescent depression and treatment.

Low social support is thought to play a key role in youth depression (Auerbach et al., 2011; Rueger et al., 2010). Specifically, lack of parental support is a predictor of higher depressive symptoms in adolescents, whereas higher support can be protective against depression (Brouillard et al., 2018; Stice et al., 2004). Greater peer and teacher support are also negatively associated with depressive symptoms (Luo et al., 2017), and there is evidence that family and teacher support prospectively predict lower depressive symptoms one year later (Pössel et al., 2018). Moreover, interpersonal characteristics associated with depression are known to impact social support. For example, Ren et al. (2018) found that depression was associated with less perceived peer support, and there is evidence that changes in depression mediate the effect of treatment on social support (Stice et al., 2011). These findings suggest a reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and low social support that may vary depending on type of support.

Other interpersonal factors, such as parental conflict, are also known to have effects on depression. Consistent with this, a relationship between greater family conflict and more severe depressive symptoms in adolescents has been observed (Brown et al., 2018; Sagrestano et al., 2003). Further, there is evidence that greater maternal conflict prospectively predicts symptoms of depression across time (Smith et al., 2019). There is also evidence that changes in depression predict changes in conflict. For example, one study found that family conflict partially predicted changes in depressed mood, with conflict and depressive symptoms showing reciprocal effects on each other over time (Kelly et al., 2016). Additionally, Howard et al. (2019) found that parental conflict did not change pre- to post-treatment, but reductions in depressive symptoms post-treatment predicted future decreases in parental conflict. Given evidence that these interpersonal factors both contribute to and are influenced by the development and trajectory of depression, it is important to consider how social support and parental conflict may affect treatment outcomes.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an effective, evidence-based treatment for adolescent depression (Compton et al., 2004; David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008; Weersing et al., 2017). Meta-analytic research indicates a moderate effect size of CBT on adolescent depressive symptoms (d = 0.53) (Klein et al., 2007). At the same time, there is considerable variability in outcomes across individuals (Weisz et al., 2006). For example, among adolescents who received individual CBT, 65% showed improvement at week 12 and 81% showed improvement at week 18 (Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study [TADS] Team, 2007). Meta-analyses have explored participant demographic and intervention-focused moderators of CBT response for adolescents (Keles & Idsoe, 2018; Klein et al., 2007); however, more research is needed to identify interpersonal predictors and moderators to be able to mitigate factors that may interfere with treatment outcomes.

Although many studies have examined the relations between conflict, social support, and depressive symptoms in adolescents, fewer have examined the impact of individual differences in interpersonal factors on treatment outcomes. There is some evidence that social support is associated with greater likelihood of acute remission with pharmacotherapy for depression in youth (Kim et al., 2021), and studies of adults with depression further indicate a link between higher social support and better response to intervention (Joseph et al., 2011; Nasser & Overholser, 2005). On the other hand, Brière et al. (2014) did not find parental or peer support to be significant moderators of the effect of group CBT on depressive symptoms in adolescents. A relatively larger literature has examined parental conflict and individual treatment outcomes in adolescents. Among adolescents receiving CBT, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), combination treatment, or a pill placebo, adolescents of mothers who reported less parent–child conflict showed more improvement in depressive symptoms, although patterns of results varied across conflict measures (Curry et al., 2006; Feeny et al., 2009). Further, Feeny et al. (2009) found that when other adolescent-reported measures of family functioning moderated the effects of CBT or CBT/medication combination treatments, adolescents who reported poorer family environments benefited less from treatment. In a sample of SSRI-resistant adolescents who received either CBT, SSRI, or a combination of CBT and SSRI treatment, less adolescent-reported family conflict at baseline predicted better clinician-rated improvement and greater symptom reduction (Asarnow et al., 2009), and clinically significant levels of parent-reported parent–child conflict predicted less likelihood of remission (Rengasamy et al., 2013). Similarly, Birmaher et al. (2000) found that in a sample of adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD), adolescent-reported parent–child conflict predicted lack of recovery, longer duration, and greater risk of recurrence of MDD. Further, another study found that high levels of school dysfunction and family dysfunction predicted worse outcomes across treatments (Gunlicks-Stoessel et al., 2010). Similarly, in a sample of depressed adolescents with comorbid substance use disorders, low family cohesion was the strongest predictor of nonresponse to group CBT with functional family therapy (Rohde et al., 2018). Overall, there is evidence to support the idea that high conflict and low social support may negatively impact treatment for depression in adolescents.

Interpersonal predictors of CBT outcomes may be particularly important to inform selections of treatments to fit the needs of individual youth (Hankin et al., 2018). Given the roles of social support and parental conflict in depression, dysfunctional relationships with parents and peers are likely to be key targets of treatment (Jacobson et al., 2018). In contrast to CBT, Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) is more directly focused on relationship difficulties that contribute to the development and maintenance of depression (David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008). Gunlicks-Stoessel et al. (2010) found that adolescents who reported high levels of maternal conflict and high levels of social dysfunction showed greater and more rapid improvements in depressive symptoms with IPT compared to treatment as usual. Emerging research also supports the efficacy of matching youth to CBT or IPT preventive interventions based on pre-existing characteristics, such that those who were matched showed lower depressive symptoms post-treatment compared to those who were mismatched (Young et al., 2021). By elucidating interpersonal predictors of CBT outcomes, we may ultimately be able to better match individuals to treatments more likely to be effective.

Compared to interventions delivered individually, group CBT may have more direct effects on interpersonal factors through interactions with peers. The efficacy of group CBT for adolescent depression is well established (David-Ferdon & Kaslow, 2008; Keles & Idsoe, 2018; Weersing et al., 2017), and group CBT is thought to be effective in part due to the involvement of peers who can provide feedback and skills training practice (Nardi et al., 2017). The Coping with Depression Course for Adolescents (CWD-A; Clarke et al., 1990) is a validated, structured psychoeducation-focused CBT program administered in a group format (Rohde et al., 2005). In addition to behavioral activation and cognitive restructuring, CWD-A includes interpersonal skills, such as social skills, effective communication, and interpersonal problem-solving. CWD-A demonstrates significant reductions in depressive symptoms and diagnoses in adolescents post-treatment, with further improvements at the 6-month follow-up (Lewinsohn et al., 1990). In depressed adolescents, the CWD-A group showed significantly higher clinician ratings of global functioning and significantly lower depressive symptoms pre- to post-intervention compared to a control group, with moderate effect sizes (ds = 0.55-0.59) (Clarke et al., 1999) and higher recovery rates (66.7%) than the waitlist (48.1%) (Clarke et al., 2002). In adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms, a CWD adaptation, Coping with Stress, has been shown to lead to greater reductions in depressive symptoms and greater improvements in social adjustment compared to supportive-expressive, bibliotherapy, and a control condition post-intervention (Stice et al., 2008), as well as greater reduction in symptoms after one year compared to brochure and bibliotherapy controls (Stice et al., 2010). In addition to potential social benefits, group CBT is more cost effective in treating depression in youth compared to individual CBT (Tucker & Oei, 2007) and allows for more efficiency in administering interventions to multiple patients at once. At the same time, group CBT offers less flexibility with scheduling than individual CBT and requires interactions with larger groups of people, which can be challenging for youth with social difficulties. The unique strengths and challenges of group CBT raise questions about how individual differences in interpersonal factors may impact group CBT outcomes.

Much of the research on adolescent depression treatment focuses on reduction in symptoms as an indicator of treatment response; however, interpersonal difficulties may also impact treatment outcomes by increasing barriers to attendance and participation in treatment. Although reductions in depressive symptoms and remission are the ultimate goals of depression treatment, there are many challenges with engaging participants in treatment to begin with. High rates of dropout have been observed across adolescent depression treatment trials (17–31%; May et al., 2007) and in youth outpatient mental health care (28–75%; de Haan et al., 2013). As such, there is a need to examine how interpersonal factors, such as social support and parental conflict, may relate to multiple indicators of treatment outcomes, including treatment attendance, completion, engagement, and improvement.

The goal of the current study was to examine individual differences in social support and parental conflict as predictors of multiple outcomes (i.e., change in depressive symptoms, session attendance, likelihood of completing treatment, clinician-rated engagement, clinician-rated improvement) following group CWD-A (Clarke et al., 1990) for adolescent depression. Given that we were predominantly interested in factors that make some youth more likely than others to respond to CBT, we used a single group design where all adolescents were assigned to CWD-A. We were particularly interested in treatment outcome indicators that were not confounded with adolescent perceptions, given that experiences of depression may bias reports of both social processes and treatment outcomes. As such, in addition to self-reported depressive symptoms, we examined objective measures of session attendance and treatment completion and clinician-rated measures of engagement and improvement. We also tested the extent to which interpersonal predictors of outcomes remained significant when accounting for baseline depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that social support and conflict would predict a variety of treatment outcomes, such that higher parental conflict and lower social support pre-treatment would be associated with higher self-reported depressive symptoms with treatment, fewer sessions attended, lower likelihood of finishing treatment, lower clinician-rated engagement, and less clinician-rated improvement.

Methods

Participants

Participants were adolescents 14 to 18 years of age (M = 15.81, SD = 1.46) with a current diagnosis of MDD and/or persistent depressive disorder (PDD) with at least moderate severity on the Clinical Global Impression Scale at intake (CGI; Guy, 1976). Participants were recruited through community advertisements and mental health clinics across two sites (7.1% from Pennsylvania State College of Medicine and 92.9% from Vanderbilt University due to a relocation of the research lab) for a study of individual differences that predict CBT outcomes for adolescent depression. Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of mania, psychosis, intellectual or developmental disability, and/or a substance use disorder severe enough to require treatment. Participants currently using antipsychotic medications and mood stabilizers were also excluded. Participants receiving other forms of treatment were included, but recent changes in pharmacotherapy (41.4% were taking antidepressant medications) or psychotherapy (45.7% were in other types of therapy) resulted in a delay in enrollment until the treatment regimen was stable for at least 30 days to avoid confounds with the onset of CBT for the study. Seventy eligible participants completed intake, 56 started group CBT, and 37 completed CBT through session 16. Participants were 65.7% female, 4.3% Hispanic/Latinx, 87.1% White/Caucasian, 4.3% Asian, 7.1% Black/African American, and 1.4% multiracial.

Procedure

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both sites. Interested participants were contacted to complete an initial screening interview with a caregiver (for minors) or participant (for those 18 years old). Prior to the start of study procedures, informed consent was obtained from participants who were 18 years old. For minors, informed consent was obtained from caregivers and assent was obtained from participants. Diagnostic clinical interviews to determine eligibility and pre-treatment self-report measures were completed during an initial intake assessment. After baseline measures, eligible participants were assigned to a CBT group to begin the intervention. Financial compensation was provided for participation in the intake interview and completion of questionnaire measures during treatment.

Participants were assigned to groups in the order in which they enrolled, with new groups beginning when at least 5 participants had completed intake assessments and were ready to begin. In cases where multiple groups were offered simultaneously, participants could choose which schedule worked best for them. Treatment was administered in a group format using the 16-session (1.5 to 2 hour sessions twice weekly for 8 weeks) CWD-A (Clarke et al., 1990). CWD-A is a structured group CBT course that includes psychoeducation, behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, social skills, relaxation techniques, and problem-solving and communication skills. All groups were led by a masters- or doctoral-level clinician with the support of a bachelors- or masters-level co-leader under the supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist (AK). Sessions were held in person in the psychology building at Vanderbilt University prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but 8 sessions for the last group (n = 5) were conducted via Zoom due to the start of the pandemic. Group leaders participated in training in CWD-A with Dr. Paul Rohde, one of the developers of the intervention, and participated in weekly group supervision to ensure adherence to the protocol and to address challenges with group dynamics. Participants who missed more than 4 sessions (25% of treatment; n = 9) due to scheduling challenges or need for higher level of care (e.g., partial hospital or inpatient program) were withdrawn from the study.

Measures

Diagnostic Interview

Current and lifetime diagnoses were determined at the initial assessment using the DSM-5 version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children 6–18 years (K-SADS-PL DSM-5; Kaufman et al., 2016) administered to adolescents by clinical psychology doctoral students or masters-level clinicians (for minors, parents were also interviewed to offer additional information on diagnoses; for n = 11 18-year-olds, only adolescent-report was obtained). All diagnoses were verified by a licensed clinical psychologist (AK). At intake, 28.60% met criteria for both current MDD and PDD (i.e., chronic MDD lasting for at least 1 year), 24.30% met for MDD only, 32.90% met for PDD with intermittent major depressive episodes (MDE) including current MDE, 8.60% met for PDD with intermittent MDE without current MDE, and 5.70% met for PDD without a history of MDE. The average age of onset for current depressive episodes was 12.88 years (SD = 2.29) with a mean episode duration of 110.71 weeks (SD = 117.23; range = 3.00–676.00, Median = 78.00). There was one statistical outlier (age 17 years) who reported chronic depression since early childhood without a two month break in symptoms. Current comorbid diagnoses included 55.70% with at least one anxiety disorder (including social anxiety, generalized anxiety, panic, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder), 17.10% with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 4.30% with oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. To evaluate inter-rater reliability, a subset of 8 audiotaped interviews were reviewed and coded by an independent interviewer. Inter-rater reliability was excellent (kappa = 1.0 for MDD diagnoses; kappa = 1.0 for PDD diagnoses).

Social Support

Adolescents completed the Social Support Questionnaire 6 (SSQ6) at intake. The SSQ6 is a brief self-report measure of perceived social support (Sarason et al., 1987). The SSQ6 has two subscales: satisfaction and number of social supports. Satisfaction for each item is rated on a scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied). A maximum of 9 social supports can be listed for each item. The internal consistency of the number of social supports was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.874). The internal consistency of the satisfaction with social supports was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.922). The average rating for social support satisfaction was 4.88 (SD = 1.08; range = 1.83–6.00). The average number of social supports reported was 1.48 (SD = 0.88; range = 0.00–6.00).

Parental Conflict

Adolescents completed the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Robin & Foster, 1989) at intake. The CBQ is a 20-item true/false self-report measure of conflict with maternal and paternal versions. Participants completed both the CBQ for mother and for father, when applicable. Out of the full sample of N = 70, 67 participants completed the CBQ for mother and 60 participants completed the CBQ for father, and participants completed the CBQ for at least one parent. Participants who reported not having regular contact with a mother-figure or father-figure did not complete the CBQ for the respective parent. The maternal CBQ had excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.917). The paternal CBQ also had excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.907). Parental conflict score was created by selecting the highest score between the report on mother and the report on father to capture the maximum amount of conflict experienced. The average maximum score of parental conflict was 7.00 (SD = 5.60; range = 0.00–19.00).

Depressive Symptoms

The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) is a 33-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms (Costello & Angold, 1987). The MFQ was administered at intake and every two weeks throughout treatment. For those who did not complete treatment, the last available MFQ was used in analyses. At intake and the final session, the MFQ had excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.938-0.944). At intake, the average score was 34.53 (SD = 14.85; range = 4.00–61.00). At the last session attended, the average score was 23.84 (SD = 13.79; range = 0.00–59.00).

Clinician-Rated Engagement

Group leaders rated participant engagement every 2 weeks throughout treatment on 3 items, including participation in sessions, completion of homework assignments, and how much they interacted with other group members in the last 2 weeks (4 sessions). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (e.g., 0 [did not attend sessions], 1 [attended but did not participate], 2 [minimally participated], 3 [sometimes participated], 4 [mostly participated]). Internal consistency for engagement was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.849). Treatment engagement was averaged across sessions for all participants who had a minimum of 3 engagement scores. Average engagement across sessions ranged from 1.00 to 4.00 (M = 3.07, SD = 0.63).

Clinician-Rated Improvement

Group leaders also rated participant improvement every 2 weeks throughout treatment using the CGI. We focused on the CGI improvement scale (CGI-I), which measures change in participants’ psychopathology since admission on a scale from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse). Improvement ratings ranged from 1.00–5.00 (M = 3.02, SD = 0.90) for the last completed treatment session.

Data Analysis

Number of social supports included two outliers. Instead of removing the values, they were modified using winsorization. Since the lower end of the data contained no extreme values, only the top 2% of data was winsorized. The two extreme values (6.00 and 4.00) were replaced with 3.75. Next, a bivariate correlation matrix was calculated with all the study variables to examine the associations between interpersonal factors, depressive symptoms, and treatment outcomes. Next, significant associations between interpersonal factors and treatment outcomes were further explored while covarying for baseline depressive symptoms using regression analyses to determine the extent to which these associations persisted accounting for symptom severity prior to treatment. Analyses were conducted in the R package lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML), which accounts for missing data by estimating the population parameter value which maximizes the likelihood function based on the sample data. To determine the extent to which clustering within CBT groups may impact results, we also repeated analyses with clustered robust standard errors (CRSE). Analyses were conducted in R with package lmtest (Zeileis & Hothorn, 2002) for regression models, package lm.beta (Behrendt, 2022) to produce standardized coefficients, and package sandwich (Zeileis, 2004) to estimate CRSE. Finally, exploratory analyses were conducted to consider predictors of depressive symptoms and age and gender as moderators. Specifically, we explored whether number of social supports, social support satisfaction, or parental conflict predicted depressive symptoms at the last session when controlling for baseline depressive symptoms. We tested age and gender as predictors and moderators of intervention outcomes.

Results

Attendance Outcomes

Fourteen participants completed baseline assessments, but chose not to start treatment (i.e., attended 0 sessions). These participants were included in the correlation and regression analyses when data were available. Of those who began treatment, the average number of completed sessions was 10.91 (SD = 4.21, range = 1.00–16.00). Including the 14 participants who did not attend any sessions, the average number of completed sessions was 8.73 (SD = 5.79, range = 0.00–16.00). Participants who did not attend any sessions did not differ from participants who attended one or more sessions on age (d = -0.08, p = 0.78), depressive symptoms at intake (d = 0.27, p = 0.37), gender (X2 = 0.25, p = 0.62), or ethnicity (X2 = 0.35, p = 0.56). There was a significant difference in race between those who did not start treatment and those who did start treatment (X2 = 10.38, p = 0.02), such that participants who identified as African American or Asian were less likely to start treatment. We also examined treatment completion as an outcome variable (i.e., attended through session 16); 66.07% of participants who started treatment, completed treatment through session 16.

Primary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between study variables are presented in Table 1. Number of social supports showed a moderate negative correlation with clinician-rated improvement (r = -0.33, p = 0.01), indicating greater improvement with more social supports. Number of social supports also showed a moderate positive correlation with likelihood of finishing treatment (r = 0.34, p = 0.01). Parental conflict was negatively correlated with clinician-rated engagement (r = -0.33, p = 0.03) and number of treatment sessions attended (r = -0.27, p = 0.02). Parental conflict was also positively correlated with clinician-rated improvement (r = 0.40, p = 0.003), indicating less improvement with more conflict. None of the interpersonal factors were significantly related to depressive symptoms post-intervention (ps > 0.35).

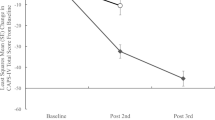

Following evidence of significant bivariate correlations between interpersonal factors and treatment outcome variables, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to determine whether the associations remained significant when accounting for baseline depressive symptoms. When covarying for baseline depressive symptoms, greater number of social supports continued to predict greater clinician-rated improvement (i.e., lower scores on the CGI-I) (b = -0.29, SE = 0.13, z = -2.24, p = 0.03) (Fig. 1). Logistic regression analyses revealed that of those who began treatment, greater number of social supports significantly predicted greater likelihood of finishing treatment (b = 1.09, SE = 0.44, z = 2.48, p = 0.01). Greater parental conflict continued to predict fewer sessions attended (b = -0.27, SE = 0.12, z = -2.24, p = 0.03) (Fig. 2), but lost significance when excluding those who did not start treatment (b = -0.18, SE = 0.10, z = -1.76, p = 0.08). Parental conflict also predicted lower clinician-rated engagement (b = -0.04, SE = 0.02, z = -2.47, p = 0.01) (Fig. 3) and less clinician-rated improvement (i.e., higher scores on the CGI-I) (b = 0.07, SE = 0.02, z = 3.23, p = 0.001) (Fig. 4).

We then conducted an exploratory analysis to determine if these relationships were better explained by either parent. Neither maternal conflict (b = -0.23, SE = 0.14, z = -1.66, p = 0.10), nor paternal conflict significantly predicted number of treatment sessions attended on their own (b = -0.23, SE = 0.14, z = -1.57, p = 0.12). Greater maternal conflict (b = -0.05, SE = 0.02, z = -2.72, p = 0.01), but not paternal conflict (b = -0.03, SE = 0.02, z = -1.48, p = 0.14) significantly predicted lower clinician-rated engagement. Greater maternal conflict (b = 0.06, SE = 0.03, z = 2.34, p = 0.02) and greater paternal conflict (b = 0.08, SE = 0.02, z = 3.32, p = 0.001) both significantly predicted less clinician-rated improvement (i.e., higher scores on the CGI-I).

Accounting for CBT Group

CRSE correlation analyses adjusting for clustering within CBT groups were generally consistent with Table 1 results, with the exception that the association between number of social supports and number of sessions attended reached significance (r = 0.28, p < 0.001) and the association between parental conflict and clinician-rated engagement lost significance (r = -0.33, p = 0.12). CRSE regression analyses were generally consistent with multiple regression results, with the exception that number of social supports significantly predicted number of sessions attended (b = 1.38, SE = 0.38, t = 3.59, p < 0.001) and parental conflict no longer predicted clinician-rated engagement (b = -0.04, SE = 0.03, t = -1.66, p = 0.11). Of note, only participants who began treatment were included in CRSE analyses as group assignment was missing for those who did not start CBT.

Exploratory Analyses

We explored the associations of social support satisfaction, number of social supports, and parental conflict with depressive symptoms at the last session when accounting for baseline depressive symptoms in regression analyses. Social support satisfaction (b = 2.65, SE = 1.44, z = 1.84, p = 0.07), number of social supports (b = 0.73, SE = 1.68, z = 0.44, p = 0.66), and parental conflict (b = 0.11, SE = 0.28, z = 0.37, p = 0.71) were not significant predictors of depressive symptoms at the last session.

Exploratory moderation analyses were conducted to test age and gender in the significant regression models. There was a significant effect of age on engagement in the model for parental conflict (b = 0.17, SE = 0.06, z = 2.80 p = 0.01). There were no other main effects of age nor gender (ps > 0.07) and neither age nor gender significantly moderated the associations between any of the interpersonal factors and treatment outcomes (ps > 0.09). Results for number of sessions attended did not change when excluding participants who did not begin treatment.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine individual differences in parental conflict and social support as predictors of group CBT outcomes for adolescents with depression, including change in depressive symptoms, number of sessions attended, likelihood of finishing treatment, clinician-rated engagement, and clinician-rated improvement. Lower number of social supports was associated with lower likelihood of finishing treatment and less clinician-rated improvement. Greater parental conflict was associated with fewer sessions attended, lower clinician-rated engagement, and less clinician-rated improvement. When accounting for baseline symptoms, these effects persisted, suggesting that more severe symptoms pre-treatment does not fully account for the negative effects of greater interpersonal problems on treatment outcomes. When accounting for clustering within CBT groups, parental conflict no longer predicted session engagement, potentially indicating that group dynamics may impact participant engagement and participation. Additionally, greater social supports predicted greater sessions attendance among those who were assigned to and started a CBT group. Importantly, social support and parental conflict were not significant predictors of change in depressive symptoms with treatment. These findings suggest that rather than group CBT being ineffective for adolescents with interpersonal problems, more difficulty attending and engaging in treatment may hinder improvement.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine interpersonal predictors of group CBT attendance in depressed adolescents. In previous studies of group CBT for adolescent depression, dropout rates did not vary by age, gender, or depressive symptoms; however, baseline interpersonal factors were not explored (Garvik et al., 2014; Idsoe et al., 2019). While it is typical to examine attrition rates to determine if the participants who did not finish treatment differ from those who did, attrition or dropout is less commonly explored as a treatment outcome. Our inclusion of likelihood of finishing treatment extends these analyses by identifying interpersonal predictors of dropout. Additionally, it is important to consider number of sessions attended as a treatment outcome because those who continued the study but attended a fewer number of sessions are not captured in attrition analyses. These groups may differ, as supported by our finding that likelihood of finishing treatment and number of sessions attended were predicted by distinct interpersonal factors.

Consistent with Brière et al. (2014) and Gau et al. (2012), we did not find that social support predicted depressive symptoms across treatment. However, social support was a significant predictor of clinician-rated improvement. These findings highlight the utility of exploring outcomes other than symptom reduction and including clinician-ratings in addition to self-report measures. Additionally, similar to prior work (Curry et al., 2006; Feeny et al., 2009; Kolko et al., 2000), we did not find that adolescent-reported parental conflict predicted depressive symptom change with CBT. However, parental conflict did predict other indicators of outcome, like clinician-rated engagement and improvement, which is generally consistent with other work linking family dynamics to CBT outcomes (Asarnow et al., 2009; Feeny et al., 2009; Rohde et al., 2018). Together, these findings indicate that high parental conflict may interfere with engagement and improvement with treatment in general, rather than the effectiveness of CBT in changing depressive symptoms.

Understanding barriers that prevent adolescents from benefitting from group CBT is necessary to deliver effective treatment. These findings carry clinical implications for improving depression treatment for adolescents. The results highlight the need address interpersonal factors that may hinder treatment attendance and engagement in group CBT. Among adolescents with low social support and high family conflict, it may be beneficial to first address these issues, perhaps with IPT, before beginning group CBT.

One limitation of this study is that the sample was relatively small, and we may have been underpowered to detect smaller effects and interaction effects. In addition, there was a high rate of participant dropout, likely due in part to severity and chronicity of participant symptoms, as well as scheduling difficulties with group sessions. Another limitation of this study is that the measures of social support and conflict were adolescent self-reports, and therefore may be subject to bias. However, given that this intervention was group CBT, adolescent perception of interpersonal factors may be more important to consider than observed measures or parent-reports. Additionally, the SSQ6 is a general measure of social support and does not differentiate source of support. Previous literature suggests that different types of social supports may have different relationships with depressive symptoms. Future research should examine if different types of support, such as parental or peer support differentially predict treatment outcomes. It should also be considered whether participants who reported low social support and high parental conflict would have the same rates of session attendance, likelihood of finishing treatment in an individual CBT program. Perhaps adolescents with more interpersonal problems are less comfortable in group settings and would show higher attendance and engagement in individual CBT. As the primary goal of this small treatment study was to test individual differences that predict response to an established intervention like group CBT, this study did not have an individual CBT condition or a control condition, and therefore, cannot conclude whether these findings are specific to group CBT or treatment in general. For this reason, future research should examine the moderating effects of these interpersonal factors on attendance and engagement in group CBT compared to other forms of treatment like individual CBT or IPT.

The current results indicate that interpersonal problems in adolescents with depression have negative effects on group CBT outcomes. Importantly, however, rather than not benefitting from group CBT, adolescents with greater interpersonal problems seem to have more difficulty engaging in treatment, as indicated by fewer sessions attended, lower likelihood of completing treatment, and lower clinician-rated engagement and improvement. Our findings highlight the need to address interpersonal issues before beginning group CBT to promote greater attendance, engagement, and improvement.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings from this study are available by request to the corresponding author.

References

Asarnow, J. R., Emslie, G., Clarke, G., Wagner, K. D., Spirito, A., Vitiello, B., Iyengar, S., Shamseddeen, W., Ritz, L., Birmaher, B., Ryan, N., Kennard, B., Mayes, T., DeBar, L., McCracken, J., Strober, M., Suddath, R., Leonard, H., Porta, G., … Brent, D. (2009). Treatment of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant depression in adolescents: Predictors and moderators of treatment response. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(3), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181977476.

Auerbach, R. P., Bigda-Peyton, J. S., Eberhart, N. K., Webb, C. A., & Ho, M. H. R. (2011). Conceptualizing the prospective relationship between social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(4), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9479-x

Behrendt. (2022). lm.beta: Add standardized regression coefficients to lm-objects. R package version 1.6–2. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lm.beta/lm.beta.

Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Kolko, D., Baugher, M., Bridge, J., Holder, D., Iyengar, S., & Ulloa, R. E. (2000). Clinical outcome after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.29

Brière, F. N., Rohde, P., Shaw, H., & Stice, E. (2014). Moderators of two indicated cognitive-behavioral depression prevention approaches for adolescents in a school-based effectiveness trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 53(1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.12.005

Brouillard, C., Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., Dionne, G., & Boivin, M. (2018). Links between the mother–adolescent and father–adolescent relationships and adolescent depression: A genetically informed study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47, S397–S408. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1350964

Brown, C. H., Brincks, A., Huang, S., Perrino, T., Cruden, G., Pantin, H., Howe, G., Young, J. F., Beardslee, W., Montag, S., & Sandler, I. (2018). Two-year impact of prevention programs on adolescent depression: An integrative data analysis approach. Prevention Science, 19, 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0737-1

Clarke, G. N., Hornbrook, M., Lynch, F., Polen, M., Gale, J., O'Connor, E., Seeley, J. R., & Debar, L. (2002). Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for depressed adolescent offspring of depressed parents in a health maintenance organization. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(3), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200203000-00010

Clarke G.N., Lewinsohn P.M., Hops H. (1990). Adolescent Coping With Depression Course. Castalia Press.

Clarke, G. N., Rohde, P., Lewinsohn, P. M., Hops, H., & Seeley, J. R. (1999). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of adolescent depression: Efficacy of acute group treatment and booster sessions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(3), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199903000-00014

Compton, S. N., March, J. S., Brent, D., Albano, A. M., Weersing, V. R., & Curry, J. (2004). Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: An evidence-based medicine review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(8), 930–959. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000127589.57468.bf

Costello, E. J., and Angold, A. (1987). Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: Checklists, screens, and nets. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(6), 726–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874C.

Curry, J., Rohde, P., Simons, A., Silva, S., Vitiello, B., Kratochvil, C., Reinecke, M., Feeny, N., Wells, K., Pathak, S., Weller, E., Rosenberg, D., Kennard, B., Robins, M., Ginsburg, G., & March, J. (2006). Predictors and moderators of acute outcome in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(12), 1427–1439. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000240838.78984.e2

David-Ferdon, C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 62–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410701817865

De Goede, I. H. A., Branje, S. J. T., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2009). Developmental changes in adolescents’ perceptions of relationships with their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9286-7

de Haan, A. M., Boon, A. E., de Jong, J. T. V. M., Hoeve, M., & Vermeiren, R. R. J. M. (2013). A meta-analytic review on treatment dropout in child and adolescent outpatient mental health care. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(5), 698–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.04.005

Feeny, N. C., Silva, S. G., Reinecke, M. A., McNulty, S., Findling, R. L., Rohde, P., Curry, J. F., Ginsburg, G. S., Kratochvil, C. J., Pathak, S. M., May, D. E., Kennard, B. D., Simons, A. D., Wells, K. C., Robins, M., Rosenberg, D., & March, J. S. (2009). An exploratory analysis of the impact of family functioning on treatment for depression in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38(6), 814–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410903297148

Ferrari, A. J., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Patten, S. B., Freedman, G., Murray, C. J. L., Vos, T., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLOS Medicine, 10(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547.

Garvik, M., Idsoe, T., & Bru, E. (2014). Effectiveness study of a CBT-based adolescent coping with depression course. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 19(2), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2013.840959

Gau, J. M., Stice, E., Rohde, P., & Seeley, J. (2012). Negative life events and substance use moderate cognitive behavioral adolescent depression prevention intervention. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 41(3), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2011.649781

Gunlicks-Stoessel, M., Mufson, L., Jekal, A., & Turner, J. B. (2010). The impact of perceived interpersonal functioning on treatment for adolescent depression: IPT-A versus treatment as usual in school-based health clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018935

Guy, W. (1976). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Moffitt, T. E., Silva, P. A., McGee, R., & Angell, K. E. (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107(1), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128

Hankin, B. L., Young, J. F., Gallop, R., & Garber, J. (2018). Cognitive and interpersonal vulnerabilities to adolescent depression: Classification of risk profiles for a personalized prevention approach. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(7), 1521–1533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0401-2

Howard, K. R., Reinecke, M. A., Lavigne, J. V., Gouze, K. R., & Jordan, N. (2019). Marital and parent-child relationships during treatment for adolescent depression: Child-driven and bidirectional effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(11), 1841–1850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00566-x

Idsoe, T., Keles, S., Olseth, A. R., & Ogden, T. (2019). Cognitive behavioral treatment for depressed adolescents: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial of a group course. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2134-3.

Jacobson, C. M., Mufson, L. H., & Young, J. F. (2018). Treating adolescent depression using interpersonal psychotherapy. In J. R. Weisz & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 66–82). The Guilford Press.

Joseph, N. T., Myers, H. F., Schettino, J. R., Olmos, N. T., Bingham-Mira, C., Lesser, I. M., & Poland, R. E. (2011). Support and undermining in interpersonal relationships are associated with treatment response to a trial of antidepressant medication. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 74(3), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2011.74.3.240.

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Axelson, D., Perepletchikova, F., Brent, D., & Ryan, N. (2016). The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia--present and lifetime version for DSM-5. https://www.pediatricbipolar.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/KSADS_DSM_5_SCREEN_Final.pdf

Keles, S., & Idsoe, T. (2018). A meta-analysis of group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) interventions for adolescents with depression. Journal of Adolescence, 67, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.05.011

Kelly, A. B., Mason, W. A., Chmelka, M. B., Herrenkohl, T. I., Kim, M. J., Patton, G. C., Hemphill, S. A., Toumbourou, J. W., & Catalano, R. F. (2016). Depressed mood during early to middle adolescence: A bi-national longitudinal study of the unique impact of family conflict. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(8), 1604–1613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0433-2

Kessler, R. C., Avenevoli, S., & Merikangas, K. R. (2001). Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 49(12), 1002–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5

Kim, H. Y., Lee, H. J., Jhon, M., Kim, J. W., Kang, H. J., Lee, J. Y., Kim, S. W., Shin, I. S., & Kim, J. M. (2021). Predictors of remission in acute and continuation treatment of depressive disorders. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 19(3), 490–497. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2021.19.3.490

Klein, J. B., Jacobs, R. H., Reinecke, M. A., & Klein, J. (2007). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: A meta-analytic investigation of changes in effect-size estimates. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(11), 1403–1413. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e3180592aaa

Kolko, D. J., Brent, D. A., Baugher, M., Bridge, J., & Birmaher, B. (2000). Cognitive and family therapies for adolescent depression: Treatment specificity, mediation, and moderation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 603–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.603

Lam, C. B., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (2014). Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 85(4), 1677–1693. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12235.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Clarke, G. N., Hops, H., & Andrews, J. (1990). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depressed adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 21(4), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80353-3

Luo, Y., Xiang, Z., Zhang, H., & Wang, Z. (2017). Protective factors for depressive symptoms in adolescents: Interpersonal relationships and perceived social support. Psychology in the Schools, 54(8), 808–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22033

Mathers, C., Fat, D.M. and Boerma, J.T. (2008). The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. World Health Organization.

May, D. E., Kratochvil, C. J., Puumala, S. E., Silva, S. G., Rezac, A. J., Hallin, M. J., Reinecke, M. J., Vitiello, B., Weller, E. B., Pathak, S., Simons, A. D., & March, J. S. (2007). A manual-based intervention to address clinical crises and retain patients in the treatment of adolescents with depression study (TADS). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(5), 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e3180323342

Nardi, B., Massei, M., Arimatea, E., & Moltedo-Perfetti, A. (2017). Effectiveness of group CBT in treating adolescents with depression symptoms: A critical review. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 29(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-0080.

Nasser, E. H., & Overholser, J. C. (2005). Recovery from major depression: The role of support from family, friends, and spiritual beliefs. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00423.x

Pössel, P., Burton, S. M., Cauley, B., Sawyer, M. G., Spence, S. H., & Sheffield, J. (2018). Associations between social support from family, friends, and teachers and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(2), 398–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0712-6

Ren, P., Qin, X., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, R. (2018). Is social support a cause or consequence of depression? A longitudinal study of adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 (8). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01634.

Rengasamy, M., Mansoor, B. M., Hilton, R., Porta, G., He, J., Emslie, G. J., Mayes, T., Clarke, G. N., Wagner, K. D., Keller, M. B., Ryan, N. D., Birmaher, B., Shamseddeen, W., Asarnow, J. R., & Brent, D. A. (2013). The bi-directional relationship between parent-child conflict and treatment outcome in treatment-resistant adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(4), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.012

Robin, A., & Foster, S. L. (1989). Negotiating parent adolescent conflict: A behavioral-family systems approach. Guilford Press.

Rohde, P., Lewinsohn, P. M., Clarke, G. N., Hops, H., & Seeley, J. R. (2005). The Adolescent Coping With Depression Course: A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach to the Treatment of Adolescent Depression. In E. D. Hibbs & P. S. Jensen (Eds.), Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: Empirically based strategies for clinical practice (pp. 219–237). American Psychological Association.

Rohde, P., Turner, C. W., Waldron, H. B., Brody, J. L., & Jorgensen, J. (2018). Depression change profiles in adolescents treated for comorbid depression/substance abuse and profile membership predictors. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(4), 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1118695

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6

Sagrestano, L. M., Paikoff, R. L., Holmbeck, G. N., & Fendrich, M. (2003). A longitudinal examination of familial risk factors for depression among inner-city African American adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.108

Sarason, I. G., Sarason, B. R., Shearin, E. N., & Pierce, G. R. (1987). A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 4(4), 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407587044007

Smith, O. A., Nelson, J. A., & Adelson, M. J. (2019). Interparental and parent–child conflict predicting adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(7), 1965–1976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01424-6

Stice, E., Ragan, J., & Randall, P. (2004). Prospective relations between social support and depression: Differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155

Stice, E., Rohde, P., Gau, J., & Ochner, C. (2011). Relation of depression to perceived social support: Results from a randomized adolescent depression prevention trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(5), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.02.009

Stice, E., Rohde, P., Gau, J. M., & Wade, E. (2010). Efficacy trial of a brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents: Effects at 1- and 2-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(6), 856–867. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020544

Stice, E., Rohde, P., Seeley, J. R., & Gau, J. M. (2008). Brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents outperforms two alternative interventions: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 595–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012645

Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Team. (2007). The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS): Long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(10), 1132–1144. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132

Tucker, M., & Oei, T. P. S. (2007). Is group more cost effective than individual cognitive behaviour therapy? The evidence is not solid yet. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 35(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465806003134

Weersing, V. R., Jeffreys, M., Do, M. T., Schwartz, K. T., & Bolano, C. (2017). Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(1), 11–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1220310

Weisz, J. R., McCarty, C. A., & Valeri, S. M. (2006). Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132

Young, J. F., Jones, J. D., Gallop, R., Benas, J. S., Schueler, C. M., Garber, J., & Hankin, B. L. (2021). Personalized depression prevention: A randomized controlled trial to optimize effects through risk-informed personalization. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(9), 1116–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.11.004

Zeileis A (2004). Econometric Computing with HC and HAC Covariance Matrix Estimators. Journal of Statistical Software, 11(10), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v011.i10.

Zeileis A, Hothorn T (2002). Diagnostic Checking in Regression Relationships. R News, 2(3), 7–10. https://CRAN.R-project.org/doc/Rnews/.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sierra Brown, Ashley Carroll, Lauren Henry, Bridget Nestor, Elizabeth Nick, Kemar Prussien, Rachel Siciliano, Emilia Cárdenas, Haley Green, and Allison Vreeland for leading and co-leading CBT groups.

Funding

This work was supported by a Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation Fellowship and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Katherine Deschner Family Young Investigator Grant awarded to A.K. Research was also supported in part by UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH. S.P. and K.H. were supported by NIH/NIMH T32-MH18921 and S.P. was also supported by NIH/NIMH 1F31-MH127817-01 during completion of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Autumn Kujawa, Lisa Venanzi, Alexandra Argiros, and Nicole Herman contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Anh Dao, Lindsay Dickey, Nicole Herman, Samantha Pegg, and Jennifer Stewart and analysis performed by Alexandra Argiros, Lisa Venanzi, and Kaylin Hill. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Alexandra Argiros and all authors contributed feedback and improved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Research Resource Identifier

Study Procedures were registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03154008.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendment or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Pennsylvania State College of Medicine and Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Boards.

Consent to Participate

For minors, written informed consent was obtained from the parents and assent was obtained from the participants. For participants 18 years old, written informed consent was obtained.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Argiros, A., Venanzi, L., Dao, A. et al. Social Support and Parental Conflict as Predictors of Outcomes of Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adolescent Depression. J Cogn Ther 16, 202–221 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41811-023-00159-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41811-023-00159-z