Abstract

During the last few years, assessment and evaluation of power quality index due to large-scale penetration of electric vehicles in the system have gained significant attention. Voltage unbalance in the low voltage distribution network is amongst the main power quality issues caused by electric vehicles and therefore it has been quantified and analyzed in this paper. A CIGRE benchmark model of low voltage distribution network is taken as test network and simulations are performed on a sample urban power distribution network. An electric vehicle grid integration and its charging model is implemented in Simulink. Results for two charging strategies including uncontrolled charging and tariff based electric vehicle charging under different electric vehicle penetration levels and uneven charging scenarios have been obtained. The presented results show that an uneven EV charging scenario can cause significant voltage unbalance that goes beyond its allowed limit of 2 %.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A typical electric vehicle (EV) is equipped with a battery bank which stores energy of some tens of kWh [1, 2]. Furnishing EVs with required amount of power may start from 1.6 kW single phase on-board charging at home to tens of kW for fast charging [3]. In case of charging an EV at home indicates most probable addition of heavy single phase loads in the residential low voltage (LV) distribution network. Nonetheless, a large-scale penetration of EVs may negatively affects distribution network multifariously because of their high demand of electrical energy and it may lead to unwanted peaks in the power consumption and consequent power quality issues including increased power flow in power cables, transformer overloading, voltage drop, voltage unbalance (VU), harmonic contamination and etc [4, 5].

Recently, some considerations have been made to discuss limitations of power system for EVs charging [6–13] and it can be considered in terms of technical as well as economic concerns where, deterioration of the power system components represent economic issues. There are different power quality parameters to be quantified including, voltage unbalances, harmonic contamination, frequency variations, voltage drop/dip [14] and their indexes are restricted by a number of relevant standards.

Nature of voltage unbalance can be conceptualized as unequal magnitudes or phase angles of voltages in a three phase system (under-voltages or over-voltages) and it can occur in both; an urban residential distribution network, where heavy single phase loads are imposed, and in rural distribution system with fairly long power distribution lines [15, 16]. Presence of negative sequence voltage components leads to large amount of current unbalance of the order of 6–10 times of voltage unbalance percent due to low negative sequence impedance in a power circuit [17]. Consequently, an excessive flow of phase currents may cause circuits of overload-protection to trip and it may also deteriorate cable insulation which results in latter’s reduced lifespan [18]. Some of its common effects include increased losses, extra heating effects, vulnerability of the system to faults because an unbalanced system might not be capable of feeding loads properly [19]. Therefore, it becomes quite important to identify and determine the presence of VU in a circuit in order to deal with it timely for trouble free operation of the power system and the connected loads.

This paper aims at summarizing and determining a power quality index, voltage unbalance in a three phase distribution system, associated with uneven EV charging. Focus of this paper is on an urban residential LV distribution network. The distribution system is based on the CIGRE LV European benchmark configuration. The distribution network is analyzed and tested under uncontrolled charging scheme and tariff based charging strategy with different penetration levels of EVs under two different Scenarios A and B. In the tariff based EV charging strategy an EV is assumed to be recharged during off-peak hours and uncontrolled EV charging is carried out on “whenever and wherever needed” basis. Additionally, a substantial increase in the load on distribution network may certainly cause a need of network reinforcements to bear the EV charging load with minimum power quality problem and thus a suggestion for network reinforcement is also given in the paper. In view of complex charging and discharging characteristics of battery, it is important to design the battery model accurately which could ensure reliable operation of the battery. This paper presents EV charging model implemented in Simulink. The EV charging is controlled via a DC/DC converter employed with constant voltage strategy.

The paper is organized as follows; types of EV charging schemes including uncontrolled EV charging scheme and tariff based charging strategy are described in “Uncontrolled EV Charging” and “Tariff Based EV Charging” section respectively. Suggested network reinforcement for connection of EVs while possibly containing voltage violation is given in “Network Reinforcement for Connecting EVs” section. Explanation of the system under study, urban residential low-voltage distribution network, is given in “System Description” section. EV charging model and corresponding control strategy are explained in “EV Battery Charging Model and its Control”. “Voltage Unbalance and Relevant Standards” contains description of voltage unbalance, its relevant standards and EV penetration scenarios. Simulation results are given in “Simulations” and the paper is concluded with discussion in “Discussion and Conclusion” section.

Uncontrolled EV Charging

In the uncontrolled charging strategy, EV charging can be freely done without any incentives and penalty for charging and restrictions respectively. In this charging plan, EVs can be connected and charged on the basis of “whenever and whenever needed”. In this charging mode EVs owner assumes electricity tariff to be constant for all day/night. Because, they are not given advantage of economic tariff during valley hours even when the grid operating conditions are flexible for bearing increase in the economic energy consumption. In case of large scale penetration of EVs, an uncontrolled charging strategy is likely to arouse voltage unbalance and other aforementioned power quality issues.

In this charging strategy, it is supposed that EV charging is done immediately after a journey is performed, depending on the state of charge (SOC) of the battery of vehicle. Where, SOC can be defined as an amount of stored energy (in %) in the battery. It majorly depends on the distance traveled by an EV and consumed energy. Mathematically, it can be written as in Eq. (1) [20]:

where, d is the distance covered by an EV during a day and AER represents all ranges of EV.

As it is assumed that EV charging can be done at any point any time during 24 h so an EV may be charged at home, work place/offices and public places. Maximum number of EVs that can be charged simultaneously at all the available charging points in the power distribution system can be formulated as:

EVs number being charged at hour h can be found as given in Eq. (2):

where \(EV_{Nr(max)}\) is the maximum number of EVs to be recharged at hour h, \(EV_{C_{t(h)}}^{HS}\) is the EV charging at home at hour h, \(EV_{C_{t(h)}}^{WP}\) is the EV charging at work place/commercial center at hour h, \(EV_{C_{t(h)}}^{PP}\) is the EV charging at public place at hour h, and \(EV_{PL}\) is the EV penetration level.

Sum of the power drawn from an LV distribution network for recharging all ranges of EVs can be expressed as in Eq. (3) and power required to charge \(EV_{Nr(max)}\) can be calculated using Eq. (4):

where, \(P_{C(h)_{EV}}\) represents power for recharging an EV, putting, \(EV_{Nr(max)}\) and \(EV_{C_{t(h)}}^{WP}=0\), Eq. (3) becomes:

where \(P_{EV_{Nr(max)}}\) is the active power required to charge \(EV_{Nr(max)}\).

Tariff Based EV Charging

In this EV charging strategy an EV is assumed to be recharged when grid operating conditions are some favourable, on contrary of uncontrolled charging in which EVs were free to be recharged anywhere, any time. As price of electricity is not fixed all the time, so EV owners can be informed about the instant tariff so that they are attracted to recharge their vehicles during valley hours. However, optimality of this charging strategy depends on EVs driver’s willingness that whether they are attracted by low tariff policy or not and in this way a part of the load of EV charging may be shifted towards optimal operating conditions. An objective of the optimal charging strategy is to minimize likelihood of strain on the power grid by urging the EV drivers to recharge their vehicles during valley hours. In this charging strategy amount of power drawn at hour h could be preferably either less than the required total charging power (as compared with uncontrolled EV charging) or equal to that. In this charging strategy high price tariff is considered during peak hours between 13:00 and 20:00 h of a day and low tariff is observed for the rest of time of 24 h [21].

Depending on the willingness of the EV driver to avail low tariff at hour h, amount of power required to recharge all ranges of EVs at a residential unit and public points is given in Eqs. (5, 6) and total power drawn from an LV distribution network for charging \(EV_{Nr(max)}\) can be expressed as given in Eq. (7).

It should be noted that in case of large-scale penetration of EVs, given that economic signal is provided to consumers, if large number of EVs are connected for recharging at the same time then it could also cause the utility grid to reach its beyond normal loading condition.

Network Reinforcement for Connecting EVs

In order to reinforce a distribution network for connection of EV charging load, multidimensional measures can be taken to enhance resilience of the distribution system such as using main fuses of bigger size, enlarging power cables, up-gradation of power circuits and or implanting additional distribution transformers to split a circuit to avoid technical violations [22, 23]. A traditionally used method for network reinforcement is about extension of the network while building secondary substation closer to load center or using enlarged power cables and such reinforcements may incur heavy costs and ecological problems due to installation of new and heavy power cables. Generally, network reinforcement costs are driven by scale of violations in terms of voltage due to demand growth. In order to ensure voltage levels within allowed limits, new transformers may be used in a circuit and the pertaining cost can be found using Eq. (8) [24].

where, \(NC_{net.}\) represents assets (circuits with addition of new transformers), \(C_{unit}\) stands for cost of a unit, and \(P_{t}\) is a proportion of network. A network reinforcement with addition of new transformer could provide an opportunity to raise voltage level in a part of the circuit and then it may be stepped down near load point. Raising a voltage level to around 1 kV and then lowering it to 0.4 kV with a suitable transformer may be a cost effective reinforcement method. The raised voltage level may be used for weaker portion of the network and suitable transformers be placed near point of consumption for lowering voltage to an appropriate level. However, insertion of new transformers must comply with standard regulations of the utility. It should also be taken into account that the transformer could equalize load among three phases of the system as it is always important for with respect to position of a consumer. In fact, the strategy could be more useful in rural zone distribution networks where a few consumers are connected to fairly long power cables. Cost of the reinforcement of an LV network depends on various factors including distance between medium voltage (MV) network and point of consumption, network location i.e., urban, rural or industrial and present condition of the existing network. This paper considers two types of network reinforcement including reinforcing power cables and inserting new transformers with raised voltage level from 0.4 kV. Directives of European Electricity Distribution Investments state information about investments for reinforced cables of the network and extracting the same information about suitable transformers from [25] helps estimates the reinforcements costs for the second case. Cost for the reinforcement based on raised voltage level at a certain segments of the line with appropriate transformers is found to be 34 % less than that of reinforced cables.

System Description

The sample system under consideration for measuring the content of unbalanced voltage in the LV distribution network is based on low-voltage European distribution systems devised by CIGRE Task Force C6.04.02 [21]. Two scenarios are taken into account with unequal distribution of EVs load on each phase of the 3-phase power system. As per low-voltage European distribution systems, sample systems include an urban residential distribution system. The benchmark LV distribution network represents a real world LV distribution system which is more user friendly and flexible for testing and analysis of distributed energy resources integration. The benchmark system consists of three distinct feeders including residential, commercial and industrial, however, this paper deals with only LV residential feeder.

Urban Residential Distribution System

In the urban feeder it is assumed that the load on all three phases of the feeder is equal before additional load of EV. Capacitance of the cables are ignored due to the cables of short lengths. The segment of connection cable, that connects load buses to the main LV feeder, has standard length of 30 m. The distribution topology is shown in Fig. 1. The transformer rating is 300 kVA with 20 kV and 400 V on its primary and secondary sides respectively. Information about number of consumers (households) at each node of the distribution system, relevant peak demand of each consumer group and the contribution of each consumer to the maximum demand of the feeder are specified in Table 1. The peak demand of N number of consumers is calculated using Eq. (9).

where \(X_{a}\) represents power demand of an individual consumer and CF stands for coincidence factor. The coincidence factor is computed using Eq. (10).

Parameters and specifications of the underground cables in the distribution network are as follows; an average mutual impedance measured in \(\varOmega \big /Km\) between nodes R1 and R2, nodes R3 and R11 and nodes R9 and R17 are 0.1855+j0.1445, 0.3343+j0.3898 and 0.1905+j0.7557 respectively and the respective lengths of the line segments are 30, 35 and 30 m.

EV Battery Charging Model and its Control

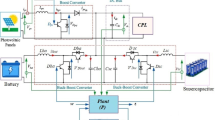

In view of complex charging and discharging characteristics of battery, the most popular and commonly used battery Li-Ion is considered here. Presently, state of the art models are combination of run time based models and Thevenin models [26]. A block diagram of EV integration with the grid is given in Fig. 2 and a model of battery charger is shown in Fig. 3. It is composed of a bi-directional DC/DC power converter, that enables two-way power transfer capability, with two switches (IGBT) controlled by a complimentary controller [27, 28]. In discharging mode of the battery with V2G concept, switch \(S_{bs}\) operates, the converter acts in boost mode, it increases the voltage \(V_{b}\) and current \(I_{b}\) in the inductor \(L_{b}\) and it flows towards capacitor \(C_{dc}\). On the other hand, in case of battery charging process, the converter acts as a buck converter when switch \(S_{bc}\) is ON and \(I_{b}\) rather flows in opposite direction from capacitor to the inductor for recharging EV battery.

For the control of the converter and of the battery charger two control circuits are needed; one is for AC/DC converter that deals with power exchange between the grid and battery charger and the other is for battery charging control. The control scheme of double loop structure is represented in Fig. 4 that contains an inner current loop and outer loop for voltage. An elaborated description of the control method can be found in [29, 30].

Voltage Unbalance and Relevant Standards

As there are numerous definitions of voltage unbalance in a power circuit, so this section describes the definition of voltage unbalance, which is under study in this paper and the relevant standards for its restriction. According to [36], it is the ratio of the negative sequence voltage component to the positive sequence voltage component present in a three phase power circuit”. Mathematically it is given in Eq. (11).

where,

where, \(V_{1}\) and \(V_{2}\) represent positive and negative sequence voltage components respectively. As EVs charging load is not evenly distributed on the three phases power system so it may contribute to widen the difference of loads among each phase of the system. This can result in different voltage drops between different phases of the system and causes unbalance voltages amongst the load buses.

In this paper, voltage unbalance factor (VUF), caused by uneven single phase EV charging, is studied and computed while considering two different EV penetration Scenarios A and B of unequal single-phase EV charging.

Scenario A: In this Scenario, load of EV charging on each phase is as follows; 50 % load is on phase “a”, phase “b” bears 30 % load and phase “c” is subjected to 20 % EV charging load.

Scenario B: In Scenario, distribution of load of EV charging on each phase is as follows; 80 % load is on phase “a”, phase “b” bears 20 % load and phase “c” has no EV charging load.

It may be noted that in the considered scenarios, it is about to demonstrate possible voltage unbalance problem that may appear due to any highly uneven distribution of EVs load on different phases in the LV distribution networks. Division of EVs charging load, on the load buses in the system, is taken in proportion to the number of households (consumer group) connected on the corresponding node.

The European Norm EN 50160 defines the limit in terms of negative to positive sequence voltage components only, as these components are truly relevant if there is turbulence on the load connected to the distribution system. According to this standard, for a period of week, the 10 min mean rms values of the voltage unbalance should not be more than 2 % under normal operating conditions. In case of unbalanced supply voltage another standard EN 61000 defined by EMC, for LV characteristics, sets the limit to 2 % only [37]. ANSI C84.1 suggests maximum voltage unbalance to 3.0 % under no-load conditions. However, as per European norms, EN 50160 and IEC 61000 are considered the most relevant standards for EV requirements and these are used as reference [38, 39].

Daily load curve of the LV distribution network (according to [21])

Simulations

The system model is simulated in SimPowerSystems and PSCAD™/EMTDC™. The battery block is taken from the toolbox Library of Matlab. In the urban residential distribution system, presence of load on each load bus is assumed to be in accordance with previously specified loads in Table 1 before addition of EVs load. Effect on the load buses is investigated with addition of EVs load with penetration levels of 40, 50 and 60 % (connecting 24, 30 and 36 EVs respectively), in an uneven manner as per Scenario A.

The impact of EV charging load in terms of voltage drop on node 15 for both Scenarios A and B are shown in Figs. 5, 6 and 7. A daily load curve taken from [21] shows the fraction/percentage of maximum power demand as an apparent power demand of the system as shown in Fig. 5 according to that EV charging could be done when the load is around 50 % of the peak load demand during midnight to 13:00 h, the load curve is observed for whole week without discrimination of working days or weekends . It could be noticed that amount of voltage drop mostly occurs during peak load hours. The voltage drop on the grid goes beyond allowed limit of 0.93 pu at various moments of the day and consequently it causes voltage unbalance among three phases of the system. Amount of voltage drop of different load buses during off-peak hours of the load curve are observed to be normal to an extent with a condition that all EVs are not plugged in at once during night time.

The number of households in the urban network is 112. As per assumed EV penetration level, according to which there would be 27 EVs in the urban area. Addition of EV charging load on each node is kept proportional to the previously connected load (before connection of EVs) and additional load. In fact, when the voltage decreases it causes load current to go higher and an then more voltage falls down further. Thus, it may result in excessive voltage drop and may limit the functionality of other sensitive loads. Additionally, rise in power consumption for a period of 24 h is illustrated in Fig. 8 for 50 and 60 % EV penetration level. It is observed that with 60 % EVs in the system, there is nearly 109 % increase in power consumption, as it changes from 23 to 49 kW. In view of obtained results, it could be noted that the network experiences a significant raise in peak load and it most likely to lead to excessive voltage drop and then voltage unbalance in the system.

The voltage unbalance factor in percent [VUF (%)] obtained at different nodes of the residential feeder under Scenario B is mentioned in Table 2 and the relevant result is shown in Fig. 9. The simulations are carried out again for different penetration levels of 15, 25 and 30 % under Scenario B. The corresponding obtained results are mentioned in Table 3 and the simulation result, shown in Fig. 10, reveal that the unbalanced load of EV charging causes the voltage unbalance to exceed allowable limit, only due to EVs load when EV penetration level is around or above 50 %. In case of, Scenario B, which is a worst unbalanced scenario, an uneven EV load of only 25 % may cause arise voltage unbalance in the distribution system. It is noteworthy, that the demonstrated results of quantified voltage unbalance factor are solely projected due to EVs integration in the system. As no EV load is connected to node load R4 and R7, so amount of voltage unbalance on them is within normal range, below 0.98 % which does not pose any issue for the power system or and the equipment as given in Tables 2 and 3.

It can always be observed that an uncontrolled EV charging is more likely to pose serious negative impact on the load buses rather a tariff based charging strategy could be of low detriment for the system. With the tariff based charging strategy, strain on the distribution system could be avoided to a limited extent, provided that off-peak hours are observed preferably in day-time or and within daily load diagram and EV drivers are attracted (by low tariff) and willing to recharge their EVs during valley hours. However, it should also be noted that an instantaneous increase in the number of EVs charging during the valley hours might also cause the system to overload, leading to provocation of technical issues in the distribution network.

The presented results shown in Figs. 11 and 12 show that employing tariff based charging helps contain the voltage unbalance factor within the standard allowed limits as the VUF is reduced to 2 % at the load nodes (NL) R16 and R17 under Scenario A and at R11, R15 and R17 in case of Scenario B.

Discussion and Conclusion

A massive adoption of electro-mobility will significantly alter the existing power system operations and practices. In view of expected large-scale penetration of EVs in the near future demands assessment and evaluation of the impact of heavy single phase EV load on the power system parameters and the relevant suggestion for possible up-gradation of the power distribution system. In this paper, a power quality index is evaluated while identifying related technical issue under various EV penetration levels and uneven charging scenarios. The presented research approach helps identify the penetration level of EVs that can be fed with power supply safely i.e., percentage of EVs that does not pose any negative impact on the system and or for which distribution system remains stable within the power quality standards.

In the first step, the distribution network is analyzed and tested under uncontrolled charging scheme with different penetration levels of EVs. It is detected that voltage unbalance content does not violate its limits till 50 % penetration level of EVs in the urban distribution system as per Scenario A. Then, the percentage of EV integration is increased by 10 % until the problem was detected. An assumption about critical mass of EVs is expected to increase until the distribution system continues to support it without exhibiting any technical violation. To prove it, another unbalanced scenario with higher number of EVs has been investigated. According to Scenario B, a technical violation is sought (voltage unbalance factor) beyond the limits when percentage of EVs of the total transportation system is only 25 %. It is noteworthy, that as no EV load in connected to load buses R4 and R7 so amount of voltage unbalance on them is within quite normal range, below 0.98 %. Considering two different charging strategies demonstrate that the tariff based charging strategy could be of low detriment for the system. The presented results show that, employing tariff based charging helps contain the voltage unbalance factor within the standard allowed limits. Additionally, it is found that the suggested technique for reinforcement of network for connection of EVs that is based on raised voltage level at certain segments of lines with insertion of appropriate transformers can help contain voltage violation to an extent and that is cost effective too as compared to traditional reinforcement strategies. It is important to consider that there may be a condition when the power distribution network is no longer able to support further EV charging load because of system parameters’ violation in the operation of network.

References

Wu, D., Aliprantis, D.C., Gkritza, K.: Electric energy and power consumption by light-duty plug-in electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 26(2), 738–746 (2011)

Li, G., Zhang, X.-P.: Modeling of plug-in hybrid electric vehicle charging demand in probabilistic power flow calculations. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 3(1), 492–499 (2012)

Clement, K., Van Reusel, K., Driesen, J.: The consumption of electrical energy of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in Belgium. In: Proceedings of 2nd Eur. Ele-Drive Transportation Conf., Brussels (2007)

Shi, R.: The dynamic impacts of electric vehicle integration on the electricity distribution grid. M.Phil thesis, Sch. of Electron. Elect. and Comp. Engg, The Univ. of Birmingham, UK (2012)

Fernández, L.P., Román, T.G.S., Cossent, R., Domingo, C.M., Frías, P.: Assessment of the impact of plug-in electric vehicles on distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 26(1), 206–213 (2011)

Zhao, L., Prousch, S., Hubner, M., Moser, A.: Impact assessment of varying penetrations of electric vehicles on low voltage distribution systems. In: Proc. of IEEE PES Transmission and Dist. Conf. and Expo., pp. 1–6 (2010)

Tikka, V., Lassila, J., Haakana, J., Partanen, J.: Case study of the effects of electric vehicle charging on grid loads in an urban area. In: Proc. of IEEE PES Int. Conf. and Exhibition on Innovative Smart Grid Techno., pp. 1–7 (2011)

Darabi, Z., Ferdowsi, M.: Aggregated impact of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on electricity demand profile. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2(4), 501–508 (2011)

Egan, M., Sullivan, D., Hayes, J., Willers, M., Henze, C.: Power-factor-corrected single-stage inductive charger for electric vehicle batteries. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 54(2), 1217–1226 (2007)

Sortomme, E., Hindi, M.M., MacPherson, S.D.J., Venkata, S.S.: Coordinated charging of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles to minimize distribution system losses. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2(1), 198–205 (2011)

Kuperman, A., Levy, U., Goren, J., Zafransky, A., Savernin, A.: Battery charger for electric vehicle traction battery switch station. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 60(12), 5391–5399 (2013)

Ul-Haq, A., Buccella, C., Cecati, C., Khalid, H.A.: Smart charging infrastructure for electric vehicles. In: Int. Conf. Clean Elect. Power, pp. 163–169 (2013)

Clement-Nyns, K., Haesen, E., Driesen, J.: The impact of charging plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on a residential distribution grid. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 25(1), 371–380 (2010)

Dugan, R.C., McGranaghan, M.C., Beaty, H.W.: Electrical Power Systems Quality. McGraw-Hill, New York (1996)

Von Jouanne, A., Banerjee, B.: Assessment of voltage unbalance. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 16(4), 782–790 (2001)

Song, H.-S., Joo, I.-W.: Source voltage sensorless estimation scheme for PWM rectifiers under unbalanced conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 50(6), 1238–1245 (2003)

Mendes, A., Cardoso, M.S.: Fault-tolerant operating strategies applied to three-phase induction-motor drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 53(6), 1807–1817 (2006)

EPRI Power Electronics Applications Center: Input performance of ASDs during supply voltage unbalance. Power quality testing network no. 28 (1996)

Anwari, M., Hiendro, A.: New unbalance factor for estimating performance of a three-phase induction motor with under- and overvoltage unbalance. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 25, 619–625 (2010)

Shafiee, S., Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M., Rastegar, M.: Impacts of controlled and uncontrolled PHEV charging on distribution systems. In: Proc. of 9th IET Internat. Conf. on Advances in Pow. Sys. Cont., Operation and Management, pp. 1–6 (2012)

Strunz, K., Hatziargyriou, N., Andrieu, C.: Benchmark systems for network integration of renewable and distributed energy resources. CIGRE Task Force C6.04.02 (2013)

Lukic, S.M., Jian, C., Bansal, R.C., Rodriguez, F., Emadi, A.: Energy storage systems for automotive applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 55(6), 2258–2267 (2008)

Lakervi, E., Holmes, E.J.: Electricity Distribution Network Design. The Institution of Engineering and Technology, London (2007)

Yan, Z., Furong, L., Zechun, H., Shaddick, G.: Quantification of low voltage network reinforcement costs: a statistical approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 28(2), 810–818 (2013)

Gustafsson, M., Schönborg, M.: Distribution system voltage of 1 kV—technical issues, regulatory requirements and system layouts, Grad. Dissertation, Dept. of Engineering, University of West Sweden (2010)

Affanni, A., Bellini, A., Franceschini, G., Guglielmi, P., Tassoni, C.: Battery choice and management for new-generation electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 52(5), 1343–1349 (2005)

Buccella, C., Cecati, C., Latafat, H.: Digital control of power converters—a survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 8(3), 437–447 (2012)

Mohamed, Y.R.: Mitigation of dynamic, unbalanced, and harmonic voltage disturbances using grid-connected inverters with LCL filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 58(9), 3914–3924 (2011)

Buccella, C., Cecati, C., Khalid, H.A., Ul-Haq, A.: On flatness-based control for series-connected VSC for voltage dip mitigation. IEEE Int. Symp. Ind. Electron. 2014, 2637–2642 (2014)

Zhou, K., Wang, D., Zhang, B., Wang, Y.: Plug-in dual-mode-structure repetitive controller for CVCF PWM inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 56(3), 784–791 (2009)

Escobar, G., Valdez, A., Leyva-Ramos, J., Mattavelli, P.: Repetitive-based controller for a UPS inverter to compensate unbalance and harmonic distortion. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 54(1), 504–510 (2007)

Mattavelli, P., Pinhabel, F., Marafao, P.: Repetitive-based control for selective harmonic compensation in active power filters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 51(5), 1018–1024 (2004)

Zhou, K., Wang, D.: Digital repetitive learning controller for three-phase CVCF PWM inverter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 48, 820–830 (2001)

Zhou, K., Low, K.S., Wang, Y., Fang-L., L., Zhang, B.: Zero-phase odd-harmonic repetitive controller for a single-phase PWM inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 21(1), 193–201 (2006)

Zhou, K., Wang, D., Zhang, B., Wang, Y.: Plug-in dual-mode-structure repetitive controller for CVCF PWM inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 56(3), 784–791 (2009)

Pillay, P., Manyage, M.: Definitions of voltage unbalance. IEEE Power Eng. Rev. 5, 50–51 (2001)

EPRI Power Electronics Applications Center, Input performance of ASDs during supply voltage unbalance, Power quality testing network PQTN Brief no. 28 (1996)

International Standard IEC 61000-4-30, Electromagnetic compatibility (EMC)—Part 4–30: Testing and measurement techniques—power quality measurement methods (2003)

EN 50160: Voltage characteristics of electricity supplied by public distribution systems (2007)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ul-Haq, A., Cecati, C., Strunz, K. et al. Impact of Electric Vehicle Charging on Voltage Unbalance in an Urban Distribution Network. Intell Ind Syst 1, 51–60 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40903-015-0005-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40903-015-0005-x