Abstract

This paper examines the impact of COVID-19 pandemic-induced lockdown on labour market in India. By using the data of centre for monitoring Indian economy (CMIE)’s consumer pyramids household survey (CPHS), the paper analyses the magnitude and nature of job losses and consequent unprecedented rise in unemployment across gender, social group, occupations during April–June 2020. It finds widespread job losses in labour market with some sections of the society, including small traders, self-employed, migrant workers, daily wage labourers, youth and women being worst affected, who mostly work in the informal sector of the Indian economy. Agriculture sector acted as a sponge by absorbing surplus labour during the times of COVID-19, which was being gradually vacated earlier over the years due to several well-known reasons. The rate of recovery in labour market has been comparatively much slower in case of salaried jobs, youth employment, particularly in rural areas and with elementary education. The economic consequences such disruptions on employment front were even much more serious as a very low percentage of households reporting improvement in their incomes. The most worrying aspect is that though the return to normalcy may take some time, there has been general recessionary trends in employment in India, which have been visible much before the COVID-19 crisis. The policy measures need to be extraordinary in such difficult times, focusing on securing employment and welfare of affected workers through sound and effective social protection programmes along with a major drive for promoting labour-intensive economic activities such as micro- and small enterprises, extension of employment security to poor urban households and skilling/reskilling of labour force to work in post-COVID-changed situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Inflicted with rapid spread of COVID-19 pandemic, the world is witnessing an unprecedented impact on public health coupled with deep shocks on economic activities and labour markets (World Bank 2020; UNO 2020). It is being termed as the worst global crisis since the Second World War (ILO 2020). India is also affected by this crisis. The gross domestic product (GDP) of the country nosedived by 23.9 per cent during the first quarter (April–June) of the fiscal year 2020–2021. Such decline in GDP is highest as compared to world’s major economies such as USA, UK, France, Germany and China. As a policy response to fight the pandemic, the Indian government has made world’s largest and stringent lockdown from the mid-night of 24 March 2020, initially for a period of three weeks, lasting till 31 May 2020 where after Government started gradual unlocking. The lockdown paused most economic activities and delivered a large aggregate supply and demand shock to the economy. The consequences have been unprecedented in scale and intensity, resulting in drastic devastation of livelihoods. According to CMIE estimates, a staggering 123.8 million persons or 30.5 per cent workers lost their employment in April 2020 over the base month of February 2020. Similarly, the number of unemployed persons spiked to 52.6 million in April 2020. The unemployment rate increased by over threefold to over 23 per cent in the months of April and May 2020 from about 7 per cent in previous months. Micro-, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) suffered hugely during this pandemic with an estimated loss of employment of 25–30 million workers by the end of June 2020 (Kumar 2020 July 22). Even with the partial lifting of lockdown since its phase 3.0, there has been gradual improvement in labour market in terms of job recoveries, and as seen in the labour market statistics for the month of June 2020, it is unlikely to see quick return to normalcy as the COVID-19 pandemic is spreading to new areas with a rise in the number of infected persons, touching to 54 lakh cases and 86,752 deaths as on 21 September 2020.

The economic fall-out of lockdown, although is widespread, few sections of the society, including small traders, self-employed, migrant workers, daily wage labourers, youth and women, are worst affected, who are mostly in the informal sector of the Indian economy (ILO 2020; Kapoor, 2020; Vyas 2020). According to latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2018–2019, nearly three-fourths of the Indian workforce is working as self-employed and casual wage labour. They are thus outside the ambit of employer–employee relationship and vulnerable to income fluctuations and outside the ambit of social security such as tenurial and income security (Kapoor 2020). Those working as regular salaried workers about 60 per cent among them do not have any job tenurial security and basic minimum social security (Kapoor 2020; Mamgain and Tiwari 2018). More so, over half of the workforce in regular salaried employment work in informal enterprises, at abysmally low wages and poor working conditions (Mamgain and Tiwari 2018).

The informal sector, which employs over 421 million of workers, is worst effected by lockdown and consequent job losses (ILO 2020). Even in the formal sector, about 53 per cent of its workforce or 49 million persons are informal workers (Mehrotra and Parida 2019), who mostly suffered layoffs due to pandemic. A majority of informal workers are self-employed mainly consisting of own account workers and family labourers (microenterprises). ILO (2020) estimates 400 million informal workers at the risk of falling under poverty due to closure of their sources of livelihoods. According to one estimate there are about 28 million migrant workers alone in urban informal sector, who work mostly at abysmally low levels of earnings and are most vulnerable to any shocks (Srivastava 2020). They wanted to return to their villages after the lockdown. Some of them could succeed, but a majority of them had to stay back in the city and reports of their struggle for food and other basic needs are no less than scary. The sectors which were severely affected by job losses are hospitality services, trade, manufacturing, real estate and repair services (ILO 2020). Agriculture sector proved to be a sector with silver lining, which not only acted as ‘employer of last resort’, but also witnessed a reasonable growth in production. However, this sector also suffered with significant losses in the sale of fruits, vegetables, flowers and poor procurement of cereals and pulses forcing many farmers to sell below minimum support prices (Narayan, 2020; Chishti 2020). The dependence on agriculture is still very high as it still engages about 60 per cent of the rural workforce, but contributes to only about one-fourth of rural household income (NABARD 2018), indicating abysmally low income for those dependent on agriculture.

The general recessionary trends in employment in India have been visible much before the COVID-19 crisis. There has been an absolute decline of nearly 6.6 million persons in workforce in 2017–2018 over the year 2011–2012 (Kannan and Raveendran 2019). About 95 per cent of job losses were in sectors such as agriculture & allied activities and mining & quarrying, manufacturing and construction. Most of the job losses were experienced by women and those with up to middle school education and residing in rural India. The reverse migration to rural areas has again crowded the rural labour markets with the onset of COVID-19 crisis. The gender dimensions of COVID-19 have been sever for women, as they not only experienced the job losses in larger proposition but also became overburdened with the unpaid care work and further restricting their entry to labour market and impacting their physical and mental health (ILO 2020).

The policy response of central as well as state governments to fight the economic crisis arising with most stringent lockdown to fight against COVID-19 health crisis has been mixed one, as has been in case of most of the countries across the globe. The Prime Minister’s Garib Kalyan Package of Rs. 1.70 lakh crore immediately after the lockdown 1.0 aimed at providing immediate relief to vulnerable population groups. The later package of Rs. 20.7 lakh crore under the rubric of Aatmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan (Self-reliance India Movement) aimed at providing relief and revival of vast range economic activities including MSMEs, farm sector and public wage works under MGNREGA. For boosting up employment opportunities in rural areas under public works programme, the Central government launched Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Rozgar Abhiyan, a public works programme on 20 June 2020 in 116 districts of six states, which witnessed reversed migration the most. With Rs. 50,000 crore additional funds the scheme aims to provide 125 days of employment by creating durable infrastructure in a mission mode (PIB 2020, 20 June). These measures are criticised for their inadequacies as a major part of such measures are repackaging of existing schemes and bank guarantees with limited injection of liquidity in the hands of workers adversely affected since the lockdown (Sen 2020; Rupavath 2020). Due to lack of any employment guarantee, like MGNREGA in rural areas, the situation of poor and vulnerable households worsened off amidst job losses. This also justifies the demand for extending employment guarantee to urban households (Dreze 2020).

It is, in this context, this paper examines in detail the labour market disruptions due to sudden nation-wide stringent lockdown imposed on 24 March 2020, lasting until May 3 and thereafter being gradually starting the unlocking process in different phases. In Section II, we analyse the magnitude and nature of job losses across gender, social group and occupations and regions. The consequent impact on unemployment is explained in Section III. Labour market disruptions during the lockdown period have also adverse impact on incomes of households, which are discussed in Section IV. The last section summarises the findings of the study.

The data

This paper is based on centre for monitoring Indian economy (CMIE)’s consumer pyramids household survey (CPHS) data, which collects longitudinal data set covering 174,405 households (roughly 10,900 households per week and 43,600 per month). Each wave is executed over a period of four months, and there are three waves in a year, and each sample household is followed three times per year. Due to its sample size larger than NSSO employment surveys, the CPHS is claimed to be all-India representative. However, its sample size for rural India is comparatively smaller which varies between 37 and 33 per cent in its recent waves. On the other hand, the share of rural sample size in PLFS is fairly high at 55 per cent. The response rate of the CPHS also got affected by pandemic as its size is reduced from around 85 per cent during 16–18 waves to lower than 65 per cent during subsequent 19 (January–April 2020) and 20 (May–July 2020) wave. The economic activity status of sample population is based on the reference day of the survey for persons in the age group of 15 years and above. In case of unemployed the data are collected as those willing to work and actively looking for a job and those willing to work and not actively looking for a job. The CPHS database, however, does not collect detailed data like the PLFS of National Statistical Office on employment and unemployment characteristics. Despite its limitations of predominantly urban sample size and lack of comprehensiveness, this became very popular source of data to understand impact of lockdown in labour market. This paper uses month-wise estimates of employed and unemployed persons for the months of April 2019, December 2019 and January 2020 onwards till June 2020. We use February 2020 as a reference normal period as lockdown became effective since 24 March 2020 and disruptions in labour market became visible from that very date.

Magnitude and nature of job losses

According to CMIE estimates, there were over 440 million persons in labour force in February 2020, consisting of both employed and unemployed persons. This number declined by nearly 71 million persons in April 2020 and thereafter tended to increase with the gradual easing of lockdown since May 2020. But still about 20 million persons were missing from labour force till the end of June 2020 (Table 1). This decline in the number of persons in labour force suggests a complete withdrawal by a sizeable number of population from participating in the labour market, particularly not reporting themselves as unemployed in the event of job losses during lockdown. The earlier period between April 2019 and February 2020 witnessed about 9 million additions in the labour force, which is a logical trend with the rise in population. Such situation of forced withdrawal from labour market arise when people do not see any alternative in a gloomy situation like lockdown and simply wait till the normalcy returns.

Before discussing about job losses in India during the lockdown period, we briefly discuss below the salient characteristics of employment as on the reference month of February 2020.

Among about 406 million workers in the age group 15 years and above in the month of February 2020, about one-tenth were women and nearly 30 per cent, SCs & STs. About one-fifth of the workforce was youth. Rural areas employed over 68 per cent of Indian workforce (Table 1). As regards occupational categories, about 28 per cent were farmers (Table 1). Over one-fifth of workforce was employed in salaried jobs. These broad features of employment were almost similar almost a year ago in the month of April 2019 except the sizeable decline in the share of workers dependent on trade and wage labour. The number of persons in workforce increased marginally by about 11 million during April 2019 and January 2020 and thereafter declined by about 4 million in the month of February 2020. These seasonal fluctuations are common characteristics of labour market. However, employment tended to decline in recent years as evidenced from NSSO and PLFS data for the period this broad of 2011–2012 and 2017–2018 (Kannan and Ravindran, 2019; Mehrotra, 2019). This has been mainly declining participation of females in rural labour markets and deceleration in employment opportunities in labour-intensive sectors such as manufacturing and construction.

Job losses associated with the lockdown can be seen in Table 1. A highest 123.4 million persons (or about 31 per cent) lost employment in the month of April 2020 over the base month of February 2020. As a result, the number of unemployed persons shoot up by 1.53 times from 34.2 to 86.8 million during the period. The labour market tended to ease after gradual unlocking process since May–June 2020, and nearly 70 million persons returned to their work by June 2020. The number of unemployed thus almost declined to half to 46.2 million persons in June 2020 as compared in the month of May 2020. However, such recovery in employment and unemployment situation in labour market was significantly lower as about 32.1 million persons were yet to find work in the month of June 2020 to reach the level of February 2020. There remained an access stock of about 12 million unemployed youth in June 2020 over the base month of February 2020 (Fig. 1).

Gender dimensions of job losses

Women constitute about one-tenth of workforce. This low share of women is due to the predominantly urban sample of the CPHS database. About 108.1 million men and 15.6 million women workers lost their jobs between February and April 2020 (Fig. 2). However, the relative impact of job losses has been comparatively higher for females as compared to their male counterparts—over 37 per cent of women workers lost their jobs as compared to about 30 per cent males workers between February and April 2020 (Table 2). The labour market started improving since May 2020 with the gradual unlocking of the economic activities—about 8 million men and 4 million women workers resumed their jobs. By June 2020 situation further improved. However, about 30 million men and 2 million women remained out of work (Fig. 2). The recovery rate has been relatively faster in case of women work force, mainly due to resumption of works under MGNREGA along with farm and non-farm activities in rural areas (Table 2).

Rural–Urban dimensions of job losses

Nearly 68 per cent of workers reside in rural India. Employment in rural areas increased by over 5 million persons between April and December 2019 and almost remained same in February 2020 with a temporary gain in January 2020. Urban employment hovered around 128 million persons since April 2019 to February 2020. Such slow growth in employment opportunities in the country is also revealed by the latest PLFS data for the year 2018–2019.

Urban areas suffered with disproportionately high number of job losses—about 43.5 million workers losing their work as compared to 80.2 million in rural areas between February and April 2020. In other words, the rate of jobs losses has been much higher at nearly 34 per cent in urban areas as compared to rural areas between February and April 2020 (Table 2). The subsequent pace of recovery after April has been relatively better in rural areas. By June 2020, rural areas and urban are short of about 20 million and 12.2 million jobs, respectively, over the figures of February 2020 (Fig. 3). It merits mention here that due to unlocking of agriculture sector in the month of April 2020, rural areas witnessed comparatively lesser pace of job losses. MGNREGA has also smoothened the rural labour market after May 2020 onwards. However, due to a significant share of non-farm activities in total rural employment (about 39 per cent), which almost remained closed during the lockdown period, the overall impact on rural labour markets has also been sizeable. Urban areas still struggle with the impact of lockdown as many of economic activities were yet to resume.

Impact on youth

Youth who constitute about one-fifth of Indian workforce suffered comparatively more job losses than others. About 29.5 million youths lost their employment between February and April 2020. This situation almost persisted till May 2020. There has been revival of 14.3 million jobs during the month of June 2020, but it was still lower by 13.9 million to the level of 83.8 million employed youth in the month of February 2020. Comparatively rural youth suffered more due to job losses than their counterparts in urban areas as is seen in the rate of decline in their employment over a reference month of February 2020 (Table 3). Unlike the general perception, most of the youth in rural areas work in non-farm enterprises such as manufacturing, construction, trade, transport and education (NSO 2019), which were severely affected by lockdown. Reverse migration to rural areas also added to the numbers of job losers and unemployed, many among them being youth.

As a result of high rate of job losses and slower recovery rates among youth as compared to those in higher age cohorts, their share in total job losses increased rapidly since April 2020 onwards—reaching as high as 54.3 per cent in rural areas and over one-fourth in urban areas (Table 4). The evidence elsewhere also shows how labour market disruptions have relatively higher adverse impact on youth, women and low skilled workers (ILO, 2020).

Impact on workers by their social groups

Among all workers in February 2020, 6.6 per cent were STs, 23 per cent SC, 40 per cent OBCs and 30.4 per cent others. The share of STs and SCs in employment tended to decrease during April 2019–February 2020, with a corresponding increase in the share of others, who mainly belong to forward castes in social hierarchies. SCs are hit hard by job losses as a highest 35 per cent of them lost their jobs immediately after the lockdown. The next highest incidence of job losses was experienced by workers belonging to others and least among STs. This pattern in job losses among workers belonging to various social groups during the period February–April 2020 significantly varied across rural and urban areas. In rural areas, SCs suffered with highest incidence (35.5 per cent) of job losses, followed by OBCs, others and least among STs. In urban areas others relatively suffered most as 38 per cent among them losing their jobs (Table 5). During the month of May 2020, the incidence of job losses tended to decline among all social groups except STs, particularly in urban areas. About two-thirds of ST workers remained without work between February and May 2020, as they were predominantly dependent on casual wage works, which were severely affected during lockout. The pace of recovery of jobs has been much better in case of OBCs but lowest among SCs during the month of June 2020. This pattern has been significantly divergent in rural and urban areas. The rate of job recovery was highest for SC workers in urban areas as it reached to almost nearer to the normalcy figures of February 2020. It has been much better for ST and OBC workers also, but not for others in urban areas. The opposite is the case in rural areas, where rate of recovery has been lowest for SCs and STs. The possible reasons for such slow recovery, particularly in case of SCs in rural areas, are largely due to lack of productive assets such as land and their overdependence on non-farm casual wage works in construction and manufacturing activities, which were very slow to recover. A faster recovery of job losses among STs and SCs in urban areas is due to resumption of self-employed and casual wage works in the month of June 2020. The slow recovery among others in urban areas is largely due to decline in white collar salaried jobs since May 2020 onwards, which were disproportionately occupied by them.

Occupation-wise job losses

The CPHS-CMIE database, as available in public domain, broadly categorizes workers into four occupational categories, i.e. businesses, salaried employees, petty traders & wage labourers and farmers. Such broad categorization does not match with the NSSO/Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) categorization of occupations. However, the precarious nature of occupations is described best by the nature of employment under three broad categories, i.e. self-employed, salaried work and casual wage labour in NSSO/PLFS data. Casual wage labour is the most precarious form of work due to its intermittent nature, whereas self-employment is a mixed bag of sub-categories predominated by own account workers and unpaid family workers with abysmally low levels of income. As is well known, the incidence of poverty is highest among casual wage labour. Regular salaried employment is relatively more stable form of employment with lowest incidence of working poor. Over half of the regular salaried jobs are in informal sector and largely bereft of any social security (Mamgain and Tiwari, 2018). This categorization throws up some revealing gaps in the available nature of employment to workforce across its gender and social group. Thus, before explaining the job losses based on CPHS-CMIE database, it will be worth to explain gender and social dimensions of quality of employment available in the country. Self-employment is a predominant form of employment employing over 54 per cent of male and nearly half of female workforce in 2017–2018. Another 27 per cent of females and 22 per cent of male workers are casual labour. Nearly 23 per cent of men and women workers are in salaried jobs. However, the prevalence of casual wage labour is almost three times higher among SC men and women workers as compared to forward caste workers. The percentage of salaried workers is lowest among STs, closely followed by SCs and OBCs, both among male and female workers. The share of salaried workers is more than double among forward caste workers as compared to STs. Also, a large proportion of self-employed forward caste workers own relatively enterprises with higher productivity. In brief, ST/SC and women are generally employed in poor quality of employment with high incidence of poverty. It is feared that these groups suffered comparatively more in their job and income loses due to lockdowns.

According to the CPHS-CMIE database, a highest 30.8 per cent of workers were working as trade and wage labour-related occupations, followed by 27.9 per cent as farmers, 21.3 per cent as salaried workers and 19.9 per cent as business persons during the month of February 2020. This occupational pattern was broadly same prior to the lockdown period except a marginal decline in the share of those in trade and wage labour-related occupations since the beginning of 2020 (Table 6). With an estimated highest number of 125 million workers in petty traders & wage labourers occupation in February 2020 in the country, they suffered with a highest 88 million or 71 per cent job losses between February and April 2020. The number of job losses in business was about 20 million workers and that in salaried employees, 18.1 million persons during this period. Agriculture has been the lone sector which witnessed an increase of 3.1 million workers as farmers during the period remained open. It acted as cushion by providing additional employment to 16.9 million workers between February and June 2020. Due to this, the share of farmers in total employment significantly increased by about 10 percentage points to 49.1 per cent in June 2020 (Fig. 4).

The fastest recovery of job losses by the month of June 2020 is seen in case of occupation group ‘business’. Recovery of jobs in occupations such as small traders and wage labour has been significant, particularly after unlock 1.0 phase since June 2020 as these occupations witnessed a nose-dive in job losses during April and May 2020. Still the employment gap in this occupational group remained highest (23.5 per cent) to reach the pre-lockdown level. A perplexing case is of salaried jobs which recorded slowest recovery with a deficit of about 17 per cent at the end of June 2020 (Table 7).

A distinct pattern of job losses and recovery is seen in rural–urban areas for the occupational groups of business and salaried jobs (Table 8). Business as occupation in rural areas suffered with comparatively lesser intensity of job losses as compared to their counterparts in urban areas due to lesser stringent lockdown. On the other hand, the fall in the number of salaried jobs was comparatively very high in rural areas, with a very slow recovery rate, which were mainly available through daily commuting in micro- and small enterprises. The share of salaried jobs in rural employment stood at 13.3 per cent and that in urban areas at 38.6 per cent in February 2020. The pace of recovery in occupational group, small traders & wage labour, accounting for 23.1 per cent of urban employment, was phenomenal after unlock 1.0 phase (Table 7). These trends also indicate that non-farm economic activities in rural areas comparatively suffered more severely with a slow pace of recovery. It is only agriculture sector which provided cushion to rural labour force by providing additional employment to 16.9 million persons between February and June 2020. This also offset the pressure of job losses in aggregate in rural labour markets.

By juxtaposing Table 5 with Table 7, it appears that the impact of job losses was much sever among SCs and STs, who work disproportionately more as wage labourers in precarious informal sector.

Education-specific impact of job losses

About 54 per cent of workforce was below secondary-level education in February 2020. They suffered with a highest incidence of job losses during April–May 2020, who were mostly working in elementary and vulnerable occupations (Table 9). The impact of job losses was relatively much less among those with secondary and senior secondary education, who constituted about one-third of workforce in February 2020. Their recovery rate has been phenomenal both in rural and urban areas, but more so in rural areas. Those with graduate degrees experienced almost no recovery as many among them lost their salaried jobs which are rather difficult to be regained in immediate future.

Trends in unemployment

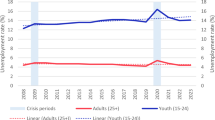

The unemployment rate hovered around 7 per cent since April 2019 till February 2020. The immediate economic consequences of lockdown have been job losses and surge in the number of unemployed persons. The number of unemployed persons jumped by 2.5 times to 52.6 million in April 2020 and further to 93.1 million in May 2020. The unemployment rate thus jumped from about 7.8 per cent in February 2020 to 23.5 per cent in April and May 2020. It eased significantly since the unlock 1.0 phase in the month of June 2020, lowering down to11 per cent (Table 10). Gender-wise, females faced high incidence of unemployment which nearly touched to a highest peak of 30 per cent between April–May 2020. Unemployment rate among women significantly declined in June 2020, reaching to lower rate than that in February 2020. This is due to their improved participation in rural labour markets and household enterprises. The situation among men was far away from the pre-lockdown rate of unemployment. Unemployment rate is generally higher in urban areas. However, the surge in the number of unemployed persons and related rate of unemployment has been equally experienced both in rural and urban areas (Table 10).

It appears that many of those losing their jobs did not report themselves as unemployed. This is seen in the decline of 71.1 million persons in labour force between February and April 2020 and 43.6 million persons between February and May 2020. This is due to the fact that many people who lost their jobs temporarily do not report themselves unemployed as they do not find any scope for work in the labour market and thus tend to withdraw from participating in it. Such discouragement effect tends to be more among females, whose LFPRs in recent years have declined significantly in recent years (Kannan and Ravindran, 2019; Mehrotra and Parida, 2019).

Though the unemployment rate is generally high among youth (over 25 per cent), it largely surged in the months of April–May 2020 due to the job losses of workers in the age group 30 years and above (Fig. 5). The share of adults among total unemployed spiked from 7 per cent in February 2020 to 57 per cent during April–May 2020 and then came down to nearly 40 per cent by June 2020. Nevertheless, youth suffered relatively more during lockdown as unemployment rate among them touched to over 40 per cent during April–May 2020 and then almost returned to the level of pre-lockdown period. Though their number declined by nearly 4 million by June 2020 over February 2020, this has been largely due to their withdrawal from labour market amidst less hopes of getting jobs. Youth thus are facing chronically a very high incidence of unemployment both in rural and urban areas but comparatively more in urban areas. As mentioned, earlier, the pace of job recovery is slow for youth as compared to others, showing their disadvantaged position in labour market, as many of them might have recently entered into employment and lost their jobs.

The most hit by lockdown are SCs. They reported a highest rate of unemployment as well as highest percentage of job losses during the months of April and June 2020 as compared to OBCs, STs and others. OBCs are next to SCs who experienced a highest incidence of unemployment. It has been lowest among others—hovering around 15 per cent in April and May 2020. With the easing of lockdown in the month of June 2020, while unemployment rate fell significantly among labour force belonging to different social groups, it remained highest at about 15 per cent among SCs. For Others, unemployment rate has reverted to the February 2020 levels (Table 11). The highest unemployment rate among SCs is primarily due to their overdependence on casual wage labour in informal enterprises which is yet to resume on a normal scale. Those who have relatively better ownership of productive assets such as land, recovered faster. This is particularly true for OBCs and STs.

Role of MGNREGA in smoothening labour market

MGNREGA has played important role in providing wage employment in rural India during the lockdown period as is seen in the data for the months of April to July during the financial years of 2019–20 and 2020–21 (Table 12). It appears that due to complete lockdown in its 1.0 phase, the demand as well as supply of MGNREGA wage employment was severely affected in rural India. It dipped to 12.9 million households demanding MGNREGA works in the month of April 2020 as compared to over 21 million households in April 2019. After the easing of lockdown restrictions on MGNREGA works since the first week of May 2020 and influx of reverse migrants to villages, a huge surge in the demand for wage employment by rural households is seen since May 2020 onwards as compared to previous year. This means that due to weakening income opportunities a large number of rural households demanded wage employment which also included reverse migrants. This is seen in the relative difference in the percentage increase in the number of households and persons demanding wage employment over the months of May–July in 2019 and 2020. With the onset of kharif cropping season in July, the demand for wage employment generally falls. This is also evidenced in Table 12. The number of households demanding wage employment declined to about 32 millions in July 2020 from about 44 million in June 2020. Thus, the kharif season though reduced the demand for MGNREGA wage labour, it is still very high—almost 75 per cent as compared to last year demand in July.

Similar surge in wage employment generation under MGNREGA is observed—reaching to a peak of 640.5 million persondays in the month of June 2020. In all, 1656 million persondays of employment was generated during April-July 2020 (Table 13). This is indeed a great achievement of committed efforts of the government, which allocated an additional Rs 40,000 crore under the MGNREGS for the current fiscal, over and above the initial budget outlay of Rs. 61,500 crore for 2020–2021. This also indicates widespread reach of government wage programme to rural households during the times of pandemic.

With this surge in employment generation under MGNREGA, the average persondays of employment per household however almost remained unchanged—ranging between 15 and 17 persondays in the months of May and June and about 13 days in the month of July during current as well as previous year (Fig. 6). In all, the average days of employment under MGNREGS per household stood at about 31.1 days during April–July 2020 period. However, the depth of the availability of employment under MGNREGA almost remained unchanged during the reference months of 2019 and 2020. In other words, though the overall amount of disposal income under MGNREGS to rural areas witnessed a huge jump, but the mean availability to each household remained unchanged. If one compares an average income of Rs. 7000/- per month per migrant worker who lost their jobs and income and returned to their villages, the compensation though MGNREGS is a meagre amount (about Rs. 2000 per month!!) It is to be seen in coming period how household incomes were impacted upon by job losses and contribution of MGNREGS to support household income in rural areas of the country.

The demand for wage employment generally remains very high during four months of April–July. During last year about 46.4 per cent of total employment was generated during these four months. Whether government was able to meet the entire wage employment demand under MGNREGA is yet another way of looking at the performance of the programme. The deficit in supply of wage employment is generally not very high, remaining much less than 20 per cent in most of the months under reference. Notably, it considerably reduced during the months of May–June 2020 as compared to last year–the deficit becoming lowest at less than 9 per cent in the month of June 2020. This is a credible achievement. However, by July 2020, the deficit level increased to about 24 per cent as compared to 17.3 per cent that in July 2019. As policy measure government can reduce this gap in the demand and supply of MGNREGA wage employment in coming months and aim at infusing more liquidity in the hands of rural households.

Impact of job losses on household income

As is well known, job losses directly reduce earnings. Such crisis has prolonged impact on loss in production and productivity, de-skilling of person associated with prolonged unemployment spells and missed opportunities to build human capital on the job that may persist for several years (Fashi et al., 2020). A steep decline of 23.9 per cent in GDP during April–June 2020 quarter shows the depth of economic crisis due to lockout. CMIE data on the perception of households about the year-to-year improvement in their incomes for the period of April–June 2019 and April–June 2020 reveal interesting patterns. First, let us look at April–June 2019 figures. The percentage of households reporting increase in their income varied from a lowest 12.2 per cent for those in the lowest income groups to over 70 per cent for those in upper most income groups. A majority of households in middle and upper income groups reported increase in their household incomes. This also shows the level of inequality in income generation. Second, the lockdown disrupted year-to-year improvement in household incomes during the reference period. The percentage of households reporting increase in their income during April–June 2020 dropped significantly across all income groups as can be seen in Fig. 7. Such impact is more visible across all income categories of households but more so to those in lowest and upper-middle income groups as none among them experienced any improvements in their incomes during April–June 2020. Contrary to this, about half of households in the highest income category experienced rise in their incomes. In middle-income group range (Rs. 0.3–1.2 million) around 10–17 per cent households reported increase in their incomes in April–June 2020. It appears that these were the households with protected salaried job workers and businessmen.

Concluding observations

The economic fall-out of world’s most stringent lockdown towards fighting COVID-19 pandemic in India has been enormous in disrupting employment and income. The recovery would certainly take longer time. The highest number of 123.8 million persons lost their employment during the first month of April 2020, affecting over 30 per cent of total workforce. The labour market thereafter tended to improve with a gradual recovery after gradual unlocking process since May–June 2020. The worst affected sections of workers included small traders, daily wage labourers, self-employed, migrant workers, youth, women and less educated, who work mostly in the informal sector. The recent data show decline in the number of white collar salaried jobs, mainly in private corporate sector due to persistence of disruptions in effective demand. The most worrying aspect is that though the return to normalcy may take some time, there has been general recessionary trends in employment in India, which have been visible much before the COVID-19 crisis. Rural India has been struggling with the declining female employment much before the pandemic crisis. The downtrend in economic growth coupled with languishing MSMEs and reduced income levels is likely to affect the effective demand for goods and services in the economy in coming months, thereby limiting the chances of growth in employment. The agriculture sector, which acted as a great cushion during the job crisis, has its own limitations to absorb additions to labour force. Just prior to crisis, agriculture was shedding out large number of workforce, who were seeking livelihoods through migration to urban areas. The past trends show that majority of employment opportunities continue to suffer with high vulnerability to seasonal fluctuations, low earnings and poor working conditions. The inequalities in labour market are likely to increase further, adversely affecting the chances of youth, women, less educated and those in elementary occupations to raise their incomes. The policy measures, therefore, should specifically focus on securing employment and welfare of these population groups through sound and effective social protection programmes. This would necessitate promoting labour-intensive economic activities such as micro and small enterprises, extension of employment security to poor urban households and skilling/reskilling of labour force to work in post-COVID-changed situations.

References

Chishti S (2020) New research: How lockdown has impacted Indian farmers, their yields. The Indian Express 22 May https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/how-coronavirus-lockdown-has-impacted-indian-farmers-their-yields-6421569/

Dreze J (2020) DUET: a proposal for an urban work programme, India Growth Centre, IDEAS for India. poverty & inequality 9 September

Fashi T, Patrinos HA, and Shafiq MN (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on labor market outcomes: lessons from past economic crises. May 20 https://blogs.worldbank.org/search?f%5b0%5d=series:881&f%5b1%5d=language:en

International Labour Organisation (2020) ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work, Second edn. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/--dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_740877.pdf

Kannan KP, Raveendran G (2019) From jobless to job-loss growth: India’s employment performance during 2012–18. Econ Polit Weekly India 54(44):38–44

Kapoor R (2020) COVID-19 and the state of India’s labour market, ICRIER policy series. 18 June

Kumar N (2020) MSMEs stare at huge job losses, soaring NPAs, cash shortage threatens survival. Economic iimes 22 July

Mamgain RP, Tiwari S (2018) Regular salaried employment opportunities in India: nature, access and inclusiveness. Indian J Labour Econ 60:415–436

Mehrotra S, Parida JK (2019) India’s employment crisis: rising education, levels and falling non-agricultural job growth, Centre for Sustainable Employment Working Paper, Azim Premji University. https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Mehrotra_Parida_India_Employment_Crisis.pdf

NABARD (2018) NABARD all India financial inclusion survey 2016–17. National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, Mumbai

Narayan S (2020) How India’s Agri-food supply chains fared during COVID-19 lockdown from farm to fork, IFPRI Blog: guest Post. International Food Policy Research Institute, 20 July

NSO (2019) Periodic labour force survey, 2017–2018 National Statistical Office. Government of India, New Delhi

PIB (2020) Pradhanmantri Garib Kalyan Rojgar Yojana. Press Information Bureau, Delhi

Rupavath P (2020) Financial package inadequate to meet pandemic impact on business in the past three months of non-operation, News Click 02 June https://www.newsclick.in/35-per-MSME-begun-shutting-shop-due-COVID-19-situation-survey

Sen P (2020) The Covid-19 shock: learnings from the past, addressing the present—II. India Growth Centre-IDEAS for India, 5 June https://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/macroeconomics/the-covid-19-shock-learnings-from-the-past-addressing-the-present-i.html

Srivastava R (2020) Understanding Circular Migration in India: its Nature and Dimensions, the Crisis under Lockdown and the Response of the State, WP 04/2020, Centre for Employment Studies Working Paper Series, Institute for Human Development, Delhi

The World Bank (2020) The global economic outlook during the COVID-19 pandemic: a changed world. Retrieved 15 June 2020 from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlookduring-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world

UNO (2020) The world of work and COVID-19. Policy Brief, United Nations Organisation

Vyas M (2020) Job losses in white and blue collar workers, Economic outlook. Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd. Mumbai, 14 September

Acknowledgements

Professor, S.R. Sankaran Chair (Rural Labour). The author is grateful to Dr. Dinesh Nayak for his valuable help. He expresses his gratitude to anonymous referees for their valuable comments. Views expressed are personal. The other usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mamgain, R.P. Understanding labour market disruptions and job losses amidst COVID-19. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 23 (Suppl 2), 301–319 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00125-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00125-x