Abstract

The high climate sensitivity of hydrologic systems, the importance of those systems to society, and the imprecise nature of future climate projections all motivate interest in characterizing uncertainty in the hydrologic impacts of climate change. We discuss recent research that exposes important sources of uncertainty that are commonly neglected by the water management community, especially, uncertainties associated with internal climate system variability, and hydrologic modeling. We also discuss research exposing several issues with widely used climate downscaling methods. We propose that progress can be made following parallel paths: first, by explicitly characterizing the uncertainties throughout the modeling process (rather than using an ad hoc “ensemble of opportunity”) and second, by reducing uncertainties through developing criteria for excluding poor methods/models, as well as with targeted research to improve modeling capabilities. We argue that such research to reveal, reduce, and represent uncertainties is essential to establish a defensible range of quantitative hydrologic storylines of climate change impacts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many planning and management decisions require an understanding of the vulnerability of hydrologic systems to a wide range of different stresses. A key challenge is to identify defensible options for the design and operation of systems under an uncertain and changing climate [61]. In the water resources sector, this requires defining a range of different climate change scenarios in order to evaluate the vulnerability of infrastructure systems and the effectiveness of different adaptation strategies in managing climate-related stresses [10, 98]. For many users, the range of climate scenarios is most compatible with decision-making processes when it is distilled into a set of discrete quantitative hydrologic “storylines” of climate change impacts, each representing key features from the full range of possible climate scenarios. While much of this paper will focus on the implications for the water resource sector, the lessons here extend across all of hydrology and, more generally, to any other field that is grappling with projecting the impacts of climate change.

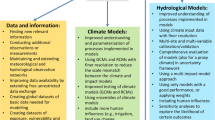

Developing quantitative hydrologic storylines of future change for the water sector is an interdisciplinary endeavor—it entails representing current knowledge of global change in the context of substantial uncertainty in the trajectory of future climate and the associated impacts on hydrologic processes. Recent research has shown the importance of assessing uncertainty from a large number of sources (Fig. 1; see also the section “Embracing uncertainty: Research to reveal and reduce modeling uncertainty”), including, global model structure [45, 56], internal climate variability [23, 24], climate downscaling methods [35, 55], and hydrologic models [1, 57, 62, 92]. Increasing computational resources permit more sources to be combined, such that model ensemble sizes have grown from a handful of experiments a few decades ago to hundreds of projections now. This plethora of available projections and methodological options is outpacing the ability of the applications community to handle large ensembles and thereby comprehensively characterize uncertainty [14]. Furthermore, it is critical to keep the application community engaged and informed to ensure that this plethora of science information can be translated into actionable water resources planning and operational decisions.

This paper provides a critical review of capabilities to characterize and understand uncertainty in the hydrologic impacts of climate change (excluding changes in water management). We conduct our review in the context of a paradigm shift in water resources planning, namely a move toward a structured decision-making (SDM) framework that tests the performance of different options that are highlighted within an envelope of broad uncertainty [10, 50, 104]. Specifically, we ask why research is needed to characterize uncertainty in climate change impacts on hydrology (“Societal and Scientific Motivations to Characterize and Understand Uncertainty” section). We consider societal motivations for appraising the potential impacts of climate change in water resources planning and management, as well as scientific motivations to understand and reduce uncertainty. We also ask how the science and applications communities are presently characterizing uncertainty (“Embracing Uncertainty: Research to Reveal and Reduce Modeling Uncertainty” section) and how the myriad uncertainties can be distilled into a discrete set of quantitative hydrologic storylines (“Embracing Uncertainty: Developing Scenarios of Hydrologic Change for Applications” section). Our broader goal is to critique the current research path and provide suggestions on ways to move the community forward in fruitful directions (summarized in the “Concluding Remarks” section). Our focus is on resolving uncertainties that are tractable through improved models and experimental design, as distinct from the uncertainties that hinge on unknowable human decision processes.

Societal and Scientific Motivations to Characterize and Understand Uncertainty

Societal Motivations

The high sensitivity of water resource systems to climate variability creates strong societal motivations to characterize and understand the uncertainty in the weather, climate, and hydrologic impacts of global warming. The United Nations Hyogo Framework for Action Footnote 1 and the World Meteorological Organisation Global Framework for Climate Services (GFCS)Footnote 2 recognize the central role played by climate information in water resources planning and management, as well as in reducing the risk of disasters associated with floods and droughts. The GFCS calls for research into fundamental climate processes and into climate impacts on people and sectors over seasonal to multidecadal timescales. Improving the effective use and communication of uncertain projections are seen as central to enhanced decision-making and more urgent action in the face of climate risks [63, 70, 71]. The effective use of uncertain climate information requires a close working relationship between the providers and recipients of climate services, as well as managing user expectations about scientific capabilities through more explicit statements about uncertainty in climate service products (Climate Services Partnership [21]).

Uncertainty about future projections is motivating a revamping of the decision rules and evaluation principles used for water infrastructure projects [10, 86, 104]. New approaches to water resources planning and management can involve moving away from the traditional search for “optimal” schemes, toward defining solutions that are better suited to “satisficing” across a range of plausible yet uncertain quantitative hydrologic storylines. The SDM framework (e.g., [32]) encompasses a very broad set of methods rather than prescribing a rigid approach for problem solving. The SDM objective therefore is to arrive at a solution that is robust and meets a given problem’s objectives by explicitly considering both uncertainty and institutional setting. Within the construct of the SDM framework, a group of methods have been developed to address uncertainty, and two widely used techniques for robustness analysis are robust decision-making and information gap analysis [5, 37, 49]. The underlying premise of these so-called robustness analysis techniques under uncertainty is not solely about predicting-then-acting but rather more generally to emphasize the evaluation of the performance of different options within the context of declared uncertainties and the minimization of potential regrets [50].

A renewed interest for research on uncertainty has stimulated the development of new tools to support the “stress-testing” of options, taking into account plausible ranges of climate variability and change [69, 87, 101]. However, there remains a need for practical guidance on defining the ranges of uncertainty used to bound stress-test experiments, especially characterizing uncertainties that have hitherto been neglected, and on the opportunities to reduce uncertainties through better methods and models (see the “Embracing Uncertainty: Research to Reveal and Reduce Modeling Uncertainty” section). Further research is also needed to assist decision makers in the timing of options within dynamic adaptation pathways approaches and in reconciling trade-offs between competing water uses when these all operate under uncertainty [72].

Scientific Motivations

A key scientific motivation for research on uncertainty is the quest to understand earth system change. In part, this involves characterizing the uncertainties in model simulations in order to focus research efforts that seek to improve process understanding and predictive models. For example, large uncertainties linked to simplified representations of clouds and precipitation have stimulated new capabilities for “cloud resolving” simulations of regional climate, which in turn have deepened our understanding of how large-scale changes in climate can affect orographic precipitation [77] and the intensity of summer convective storms [42]. In this context, uncertainty characterization is necessary to separate climate “signal” from “noise”, i.e., to identify changes where we have some confidence, such as declining snowpack [64]. Additional research to characterize climate and hydrologic modeling uncertainty will strengthen the scientific foundation for specifying national and international policy actions aimed at mitigating climate change.

Embracing Uncertainty: Research to Reveal and Reduce Modeling Uncertainty

The process of defining quantitative hydrologic storylines of climate change impacts for the water sector has been an active area of research for nearly two decades [8, 12, 22, 38, 99, 104]. Recent research is beginning to reveal how different methodological choices can impact portrayals of climate risk [1, 4, 35, 39, 58, 59, 73, 92, 95]. Quantitative hydrologic storylines of climate change impacts for the water sector must encompass, as much as possible, the full suite of uncertainties associated with (1) global climate modeling, including both model uncertainty and unforced climate variability, (2) regional climate downscaling, and (3) hydrologic modeling. Although not discussed here, such storylines should also reflect indirect consequences of climate variability and change (including hydrologic responses mediated by changes, e.g., in land use or atmospheric chemistry such as dust and aerosols) as well as pertinent non-geophysical factors (such as the operational regimes of water infrastructure).

The approach we advocate here is illustrated schematically in Fig. 1, following three main steps. First, it is important to adequately characterize uncertainty in all elements of the climate impacts modeling chain, including uncertainty in emissions scenarios, uncertainty in selection and configuration of climate models, uncertainties in internal climate system variability (characterized by small perturbations in climate model initial conditions), uncertainty in climate downscaling, uncertainty associated with the selection and configuration of hydrologic models, and uncertainty in hydrologic model calibration. Many of these uncertainty sources are neglected in climate impact studies. Second, it is important to reduce uncertainties, though selection of likely emission scenarios, informed sampling of climate models (e.g., model culling), sampling of internal climate system variability, restriction to more reliable climate downscaling methods, selection of hydrologic models with adequate process representation, and estimating parameters in hydrologic models using multivariate/multiobjective methods that ensure high model process fidelity, not just high Nash-Sutcliffe efficiencies. Third, from a practical perspective, it is important to construct a small set of example quantitative hydrologic “storylines” of climate change impacts to provide end-users of climate information with a manageable set of scenarios they can use in their planning studies. The storylines proposed here are more specific than the general climate change narratives proposed by Yates et al. [104], as the focus is on explicitly characterizing all sources of uncertainty in the modeling process. The following sections will describe the construction of quantitative hydrologic storylines in more detail, focusing on the research that is needed to characterize and reduce uncertainties at various points in the climate impacts modeling chain.

Global Climate Modeling

Advances in global climate modeling are yielding more detailed representations of earth system processes and feedbacks. The specific decisions made when building climate models (often equally plausible and equally defensible modeling strategies), along with the chaotic evolution of climate system states, mean that increases in model complexity are often accompanied by increases in the diversity of simulations of future climate [45]. Such diversity in climate model simulations is a positive attribute, as output from multiple models provides the starting point to define alternative climate change storylines that have value for evaluating water sector options [8, 9, 74].

It is difficult to characterize uncertainties in climate model simulations from the available multiple global climate model ensemble. This is because uncertainties in climate modeling are not explicitly encapsulated in the differences among the climate models that are available for impact assessments [46, 66, 85]. As such, the available ensembles do not span the range of possible physical representations, and they conflate modeling error with natural, chaotic, variability. Consequently, climate models offer at best a biased and incomplete sample of the range of possible climate futures [7]. Moreover, global climate models may not properly represent natural, unforced climate variability, which can introduce substantial uncertainty in assessments of climate changes on decadal to multidecadal time scales [23, 24]. One solution is to improve the estimation of each model’s forced climate signal by using sufficiently large ensembles from single-physics climate model implementations that differ only in their initial conditions [41], a practice that may prove computationally impractical for many modeling groups. Another solution is to generate perturbed physics ensembles [66], though this is also costly as well as logistically difficult to apply across multiple models in a consistent and coordinated way.

Another challenge is to reduce uncertainties in global climate model simulations. As noted above, collective increases in model complexity can actually increase model diversity because different modeling groups make various model development decisions that ultimately impact model simulations. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to accept that all models are not created equal (i.e., some are better than others [44] for a given objective), engendering an opportunity for methods to cull or down-weight models. At present, attempts to do so typically employ criteria based on historical model performance which ostensibly reflect the adequacy of model representations of earth system processes [97]. For instance, the ability to balance evaporation with precipitation at global scales might be regarded as a fundamental test of a climate model’s fitness for hydrological applications [51]. Clearly, however, such test metrics must be multifaceted, which leads inevitably to the further challenge of defining and agreeing upon criteria for model assessment—a problem likely to be viewed variously from different societal and scientific perspectives. For example, the ability to represent important features of the climate system such as the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), or the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) might be viewed as key metrics for the evaluation of any climate model regardless of the proposed application. A vexing gap in the model weighting effort, however, has been the dearth of accepted criteria to rate a model’s representation of earth system sensitivities to emission forcing—that is, the model’s ability to provide an accurate answer to central questions about future earth system impacts given climate change. Nonetheless, reducing uncertainty through the selection/rejection of climate models is an active area of research, and many groups are experimenting with alternative methods to combine output from multiple climate models [6, 13, 29, 46, 65]. As the community moves to higher resolution models, it will be interesting to see how explicitly resolving processes (e.g., convection, flow over mountain ranges) changes the profile of inter-model differences.

Climate Downscaling

Advances in regional climate downscaling have been somewhat mixed. The key advances in statistical downscaling were made over two decades ago, with recent work focused primarily on refining traditional methods (see the reviews of Fowler et al. [31]; Wilby and Fowler [100]). Non-stationarity in statistical downscaling model parameters is widely recognized as a key problem, but has yet to be seriously characterized or resolved by the community, creating considerable uncertainty in how climate change is portrayed. One approach is to use very high-resolution regional climate models as “virtual worlds” to explore the stationarity of predictor-predict and relationships (following the seminal work of Charles et al. [11]). In contrast to statistical downscaling, dynamical downscaling capabilities have evolved considerably. Such advances are spurred in part by advances in computing, and in part by advances in physics parameterizations [77], though characterizing uncertainty in dynamical downscaling remains challenging [27, 55]. The age-old quest to characterize and reduce uncertainties is accentuated by the gap between science and applications, prompting Fowler and Wilby [30] to call for more thinking about the transposition of insights about downscaling uncertainties into adaptation practice.

Recent research on regional climate downscaling has revealed a number of uncertainties that have hitherto been largely neglected by the water management community. Considering parsimonious statistical models, Gutmann et al. [35] conducted a comprehensive assessment of the climate model re-scaling methods commonly used by the water management community in the USA, revealing substantial biases, inadequate representation of extremes, and inadequate representation of the spatial scaling characteristics that are important for hydrology. The work suggests that techniques that statistically re-scale the global model change signals are undermined by methodological artifacts that compromise their utility for planning studies. Considering complex dynamical models, Mearns et al. [55] evaluate the results from the coarse-resolution North American Regional Climate Change Assessment Program (NARCCAP) and reveal that many regional climate model simulations have very different climate change signals to the parent global model. The NARCCAP findings call into question the notion that the use of high-resolution physical parameterizations guarantees that a dynamical downscaling will provide a more precise and accurate regional change projection. Because the choices of parameters and physics parameterizations in regional dynamical downscaling models also give rise to significant uncertainty in projected change signals, a computationally tractable method for exploring and understanding these uncertainties is a critical need. The perturbed physics approach is a key effort to characterize climate dynamical downscaling uncertainties [67, 103] and is now being applied using high-resolution intermediate complexity atmospheric models [36].

The scope for reducing uncertainty in climate downscaling parallels that in global climate modeling, i.e., avoiding, to the extent possible, the use of physically inadequate models and methods. Put simply, it is important to select among a range of downscaling methods based on their historical performance [90], including their ability to adequately represent extremes, temporal sequencing (e.g., wet spell length), and the spatial scaling characteristics that are important for hydrology [35]. As noted previously, dynamical downscaling methods have shown substantial improvements when moving to higher resolutions. In particular, when dynamical models reach sufficient resolution that the convective parameterization can be turned off and mountain ranges are properly resolved (e.g., [3, 42, 77]), then there may be more agreement between models. A critical remaining challenge for the community, as noted earlier, is to assess the ability of downscaling methods to represent change in local-to-regional scale climate and hydrology [76]. As with global climate modeling, therefore, the selection of downscaling methods must proceed with caution, to avoid unintended consequences of over-correcting the noise in climate model simulations (e.g., interpreting internal variability as a model bias) and to avoid being overly confident in the change signal from the global models [28, 35].

Hydrologic Modeling

The last decade brought a greater appreciation for how decisions in hydrologic modeling can affect the portrayal of climate change impacts. Wilby [96] demonstrated that uncertainties associated with the non-uniqueness of model parameters had a large impact on the portrayal of climate change impacts. More recently, others have emphasized the large impacts associated with the choice of hydrologic models [59, 92], with traditional calibration approaches having limited impact in reducing inter-model differences in the portrayal of climate change signals, even for physically motivated models [58]. The challenges of characterizing and reducing uncertainties are therefore very acute in the hydrologic modeling community.

Specific limitations of existing hydrologic modeling approaches relate to both (1) missing processes and (2) inadequate model parameters. In terms of resolving dominant processes, many modeling groups follow a mechanistic modeling approach in order to provide increased confidence that results will hold under different climate regimes [18]. However, many climate impact studies are still conducted using simplistic models that are not robust to non-stationarity [94]. For example, models that parameterize potential evapotranspiration as a function of air temperature can exaggerate the hydrologic sensitivity to climate change [60, 78, 84]. Similar issues arise from neglecting processes such as vegetation change, carbon fertilization, and surface water-groundwater interactions [54, 75]. Even when models are relatively “complete” in terms of their representation of dominant processes, different model formulations lead to very different simulations of hydrologic processes and land-atmosphere feedbacks [15, 17, 25, 48]. In terms of improving model parameters, for catchment-scale studies, there is too often a reliance on a curve-fitting approach to parameter estimation, leading to compensatory model errors and poor representation of dominant hydrologic processes [43]; similarly, for regional- and continental-scale studies, there is too often a reliance on a priori model parameters that also provide a poor representation of dominant processes [2]. There is an interesting interplay here between processes and parameters—while we advocate mechanistic modeling, physically motivated models have hundreds of parameters that are at best ill defined. We do not even know the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the soil to within an order of magnitude, much less the vertical rooting profiles, soil thickness, interception capacity, and so forth. While we can estimate these parameters globally, they are very crude estimates, and the uncertainty in those parameters translates into large uncertainties in the climate change signal. A key research effort is therefore to better characterize hydrologic modeling uncertainties, using modeling frameworks designed to accommodate multiple spatial configurations, multiple process parameterizations, and multiple model parameter values and explicitly represent the myriad uncertainties in physically motivated models [16, 19, 20].

Opportunities to reduce uncertainty in hydrologic modeling arise from the judicious selection, configuration, and calibration of hydrologic models, guided by physical insights about the studied hydrologic system. Concerning selection, research effort is focused on developing models that appropriately represent the dominant hydrologic processes [18] because neglecting processes (e.g., groundwater-surface water interactions) or over-simplifying process representations (e.g., temperature index snow models) leads to unreliable portrayals of climate change impacts [52, 60]. Concerning model parameters, research effort is focused on implementing diagnostic and multiple objective approaches to parameter estimation to avoid problems associated with compensatory parameter interactions and parameter non-uniqueness [33] and hence reduce model uncertainty by selecting parameter sets that faithfully represent observed hydrologic processes. As just mentioned, estimates of model parameters are especially uncertain for continental-domain hydrologic model applications [62], and dedicated research effort on such large-domain applications can substantially reduce model uncertainty [81].

Embracing Uncertainty: Developing Scenarios of Hydrologic Change for Applications

Quantitative hydrologic storylines of climate change impacts for the water sector must, to the extent possible, encompass the full suite of uncertainties associated with global climate modeling, climate downscaling, hydrologic modeling, and natural climate variability [1, 22, 26, 58, 83, 92, 99]. Recent research has revealed that the water management community has hitherto neglected or underestimated many of the uncertainties in climate change scenarios, in particular, uncertainties associated with internal climate system variability [23, 24, 39] and hydrologic modeling [58, 92]. Other work has revealed several issues with commonly used climate downscaling methods, which can hinder portrayals of the hydrologic impact of climate change [34, 35, 62].

The selection problem represents an important research challenge because of the need to sample from the very large ensemble in an objective fashion. While some progress has been made on this topic [14, 46, 47, 53, 88, 102], existing techniques typically focus primarily on one aspect of the problem, be it model fidelity Footnote 3 [80, 89], sensitivity Footnote 4 [79, 91], or diversity Footnote 5 [6, 47], with little work on the interplay among these factors [82, 93]. Importantly, there is limited understanding on how considerations of fidelity, sensitivity, and diversity informs sampling from the hierarchy of models used to evaluate impacts of climate change in the water resources sector, including global climate models, climate downscaling, and hydrologic models.

Moving forward, it is important to create quantitative hydrologic storylines that reflect these myriad uncertainties. Figure 1 illustrates such an approach, emphasizing the research needed to characterize uncertainties, to reduce uncertainties, and to develop hydrologic storylines for specific end-user applications. A key component of this research (not shown here) is also to reflect uncertainties in the management models and other non-climate stresses that play a strong role in defining possible futures and the effectiveness of different water management options.

In this context, it is also important to move beyond the direct consequences of changed air temperature (ΔT) and precipitation (ΔP) regimes on water supply and consider a wide range of indirect hydrological impacts and dynamics implied by ΔT and ΔP that are not captured in traditional climate change assessments. For example, increased aridity may suggest enhanced dust supply and deposition on snow/ice pack leading to earlier or more rapid melt; changed patterns of biomass accumulation and desiccation could alter wildfire then subsequent flood and landslide hazards; variations in soil moisture and temperatures could favor disease/pest outbreaks and dieback of forest cover; drier/hotter conditions could drive greater demand for outdoor water use in urban areas. Yates et al. [104] assert that these types of narratives should be used to stress-test water supply systems and adaptation options in more convincing, holistic ways. More generally, the storyline approach opens the way for including non-climatic pressures, which may be of more immediate concern.

Concluding Remarks

Quantitative storylines of future hydrologic change must encompass the full suite of uncertainties associated with global climate modeling, climate downscaling, hydrologic modeling, and natural climate variability [1, 22, 58, 83, 92, 99], and ultimately, this information must be put in a context such that the water resources planning and management community can incorporate uncertain climate information along with expectations of other changes in order to make informed decisions. This paper reviews how uncertainty is encapsulated in simulations of future change throughout the modeling process. We discuss research that reveals uncertainties that have hitherto been neglected (e.g., due to poor models and methods and internal climate variability). We also point to research that can reduce uncertainties throughout the set of models and methods that are used to understand the climate sensitivity of water resources (reducing uncertainty through model selection/rejection, and focusing science attention on critical and unmet model development needs). Our review is conducted within the context of a paradigm shift in water resources planning, where the focus has moved to a SDM framework that tests the performance of different options within the context of uncertainties [10, 50, 104].

Our broader goal is to critique the current research path and provide suggestions on ways to move the community forward in fruitful directions. Key research priorities include:

-

Improved characterization of uncertainty in global climate models, by enhancing development and use of perturbed physics and initial condition ensembles, and additional research on the selection/rejection of climate models.

-

Improved characterization of uncertainty in regional climate downscaling, by (a) enhancing development of perturbed physics approaches (including more extensive use of dynamical models of intermediate complexity), (b) further development of statistical downscaling methods that can represent metrics important for hydrology (spatial scaling characteristics; extremes), and (c) abandoning downscaling methods that have limited merit for hydrologic impact studies.

-

Improved characterization of uncertainty in hydrologic modeling, using frameworks designed to accommodate multiple spatial configurations, multiple process parameterizations, and multiple model parameter values; reducing hydrologic model uncertainty through advances in hydrologic process representation (explicitly simulate dominant processes and improving estimates of model parameters, especially for continental-domain applications).

-

Use comprehensive characterizations of uncertainty in global climate modeling, climate downscaling, land-atmosphere feedback processes, and hydrologic modeling to develop quantitative hydrologic “storylines” describing trajectories of hydrologic change that reflect these myriad uncertainties.

Under the backdrop of uncertainty, it is also important to emphasize areas where we have gained new knowledge and understanding in order to provide meaningful guidance for water resources planning and management. In particular, it is important to identify changes in climate and hydrologic processes where we have some confidence, such as declining snowpack, using quantitative concepts such as the emergence of statistically significant signals, or where a number of changes occur in ways that improve signal to noise. With this understanding in hand, it is also important to improve the use and communication of uncertain projections by enhancing the working relationship between the providers and recipients of climate services, as well as managing user expectations about scientific capabilities through more explicit statements about uncertainty in climate service products and where the results are most robust.

We argue here that twenty-first century water resource planning creates a strong need for more holistic depictions of uncertainty. It is time to move beyond the common ad hoc approach of defining a limited set of climate change scenarios based on a small collection of models and methods with known problems. Instead, we advocate a more deliberate approach to assessing hydrologic uncertainty under climate change, that is, at the same time, counterbalanced by the need for more value-added explicit modeling [40, 76]. This creates a need for new tools and techniques for generating local-to-regional climate and hydrology scenarios for vulnerability assessment and adaptation options appraisal [68, 101]. Such research into revealing, reducing, and representing uncertainties is essential for defining plausible ranges of quantitative hydrologic storylines of climate change impacts to support water resources planning and management.

Notes

Fidelity is the extent to which a model faithfully represents observed processes, as measured by comparing historical model simulations to observations. The suite of metrics used to evaluate model fidelity is very important.

Sensitivity is the extent to which the model is sensitive to changes in the parameters of the simulation, e.g., the sensitivity of a model to change in boundary forcing.

References

Addor N, Rössler O, Köplin N, Huss M, Weingartner R, Seibert J. Robust changes and sources of uncertainty in the projected hydrological regimes of Swiss catchments. Water Resour Res. 2014;50:7541–62.

Archfield SA, Clark MP, Arheimer B, Hay LE, McMillan H, Kiang JE, et al. Accelerating advances in continental domain hydrologic modeling. Water Resour Res. 2016. doi:10.1002/2015WR017498.

Ban N, Schmidli J, Schär C. Heavy precipitation in a changing climate: does short-term summer precipitation increase faster? Geophys Res Lett. 2015;42:1165–72.

Bastola S, Murphy C, Sweeney J. The role of hydrological modelling uncertainties in climate change impact assessments of Irish river catchments. Adv Water Resour. 2011;34:562–76.

Ben-Haim Y. Info-gap decision theory: decisions under severe uncertainty. Academic Press; 2006.

Bishop CH, Abramowitz G. Climate model dependence and the replicate Earth paradigm. Clim Dyn. 2013;41:885–900.

Boberg F, Christensen JH. Overestimation of Mediterranean summer temperature projections due to model deficiencies. Nat Clim Chang. 2012;2:433–6.

Brekke LD, Maurer EP, Anderson JD, Dettinger MD, Townsley ES, Harrison A, et al. Assessing reservoir operations risk under climate change. Water Resour Res. 2009;45

Brown C, Wilby RL. An alternate approach to assessing climate risks. Eos, Trans Am Geophys Union. 2012;93:401–2.

Brown C, Ghile Y, Laverty M, Li K. Decision scaling: linking bottom-up vulnerability analysis with climate projections in the water sector. Water Resour Res. 2012;48

Charles SP, Bates BC, Whetton PH, Hughes JP. Validation of downscaling models for changed climate conditions: case study of southwestern Australia. Clim Res. 1999;12:1–14. doi:10.3354/cr012001.

Christensen NS, Wood AW, Voisin N, Lettenmaier DP, Palmer RN. The effects of climate change on the hydrology and water resources of the Colorado River basin. Clim Chang. 2004;62:337–63.

Christensen J, Kjellström E, Giorgi F, Lenderink G, Rummukainen M. Weight assignment in regional climate models. Clim Res. 2010;44:179–94.

Christierson B, Vidal J-P, Wade SD. Using UKCP09 probabilistic climate information for UK water resource planning. J Hydrol. 2012;424:48–67.

Clark MP, Slater AG, Rupp DE, Woods RA, Vrugt JA, Gupta HV, et al. Framework for Understanding Structural Errors (FUSE): a modular framework to diagnose differences between hydrological models. Water Resour Res. 2008;44. doi:10.1029/2007WR006735

Clark MP, Kavetski D, Fenicia F. Pursuing the method of multiple working hypotheses for hydrological modeling. Water Resour Res. 2011;47, doi:10.1029/2010WR009827.

Clark MP, Nijssen B, Lundquist JD, Kavetski D, Rupp DE, Woods RA, et al. A unified approach for process-based hydrologic modeling: 1. Modeling concept. Water Resour Res. 2015;51:2498–514.

Clark MP, Fan Y, Lawrence DL, Adam JC, Bolster D, Gochis D, et al. Improving the representation of hydrologic processes in Earth System Models. Water Resour Res. 2015. doi:10.1002/2015WR017096.

Clark MP, Nijssen B, Lundquist J, Kavetski D, Rupp D, Woods R, et al. A unified approach to process-based hydrologic modeling. Part 1: modeling concept. Water Resour Res. 2015c;51. doi:10.1002/2015WR017198.

Clark MP, Nijssen B, Lundquist J, Kavetski D, Rupp D, Woods R, et al. A unified approach for process-based hydrologic modeling: part 2. Model implementation and example applications. Water Resour Res. 2015d;51. doi:10.1002/2015WR017200.

Climate-Services-Partnership. Toward and ethical framework for climate services, White Paper prepared by the Climate Services Partnership Work Group on Climate Service Ethics. 2014. p 12.

Davie J, Falloon P, Kahana R, Dankers R, Betts R, Portmann F, et al. Comparing projections of future changes in runoff from hydrological and biome models in ISI-MIP. Earth Syst Dyn. 2013;4:359–74.

Deser C, Phillips A, Bourdette V, Teng H. Uncertainty in climate change projections: the role of internal variability. Clim Dyn. 2012;38:527–46.

Deser C, Knutti R, Solomon S, Phillips AS. Communication of the role of natural variability in future North American climate. Nat Clim Chang. 2012;2:775–9.

Dirmeyer PA, Gao X, Zhao M, Guo Z, Oki T, Hanasaki N. GSWP-2: multimodel analysis and implications for our perception of the land surface. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2006;87:1381–97.

Dobler C, Hagemann S, Wilby R, Stötter J. Quantifying different sources of uncertainty in hydrological projections in an Alpine watershed. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2012;16:4343–60.

Done JM, Bruyere CL, Ge M, Jaye A. Internal variability of North Atlantic tropical cyclones. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2014;119. doi:10.1002/2014JD021542.

Ehret U, Zehe E, Wulfmeyer V, Warrach-Sagi K, Liebert J. HESS Opinions “Should we apply bias correction to global and regional climate model data?”. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2012;16:3391–404.

Evans JP, Ji F, Abramowitz G, Ekström M. Optimally choosing small ensemble members to produce robust climate simulations. Environ Res Lett. 2013;8:044050.

Fowler HJ, Wilby RL. Beyond the downscaling comparison study. Int J Climatol. 2007;27:1543–5. doi:10.1002/joc.1616.

Fowler H, Blenkinsop S, Tebaldi C. Linking climate change modelling to impacts studies: recent advances in downscaling techniques for hydrological modelling. Int J Climatol. 2007;27:1547–78.

Gregory R, Failing L, Harstone M, Long G, McDaniels T, Ohlson D. Structured decision making: a practical guide to environmental management choices. Wiley; 2012.

Gupta HV, Wagener T, Liu YQ. Reconciling theory with observations: elements of a diagnostic approach to model evaluation. Hydrol Process. 2008;22:3802–13. doi:10.1002/hyp.6989.

Gutmann ED, Rasmussen RM, Liu C, Ikeda K, Gochis DJ, Clark MP, et al. A comparison of statistical and dynamical downscaling of winter precipitation over complex terrain. J Clim. 2012;25:262–81. doi:10.1175/2011JCLI4109.1.

Gutmann E, Pruitt T, Clark MP, Brekke L, Arnold J, Raff D, et al. An intercomparison of statistical downscaling methods used for water resource assessments in the United States. Water Resour Res. 2014. doi:10.1002/2014WR015559.

Gutmann E, Barstad I, Clark MP, Arnold JR, Rasmussen RM. The intermediate complexity atmospheric research model. J Hydrometeorol. 2016;17:957–73. doi:10.1175/JHM-D-15-0155.1.

Hall JW, Lempert RJ, Keller K, Hackbarth A, Mijere C, McInerney DJ. Robust climate policies under uncertainty: a comparison of robust decision making and info‐gap methods. Risk Anal. 2012;32:1657–72.

Hamlet AF, Lettenmaier DP. Effects of climate change on hydrology and water resources in the Columbia River Basin1. JAWRA J Am Water Resour Assoc. 1999;35:1597–623.

Harding B, Wood A, Prairie J. The implications of climate change scenario selection for future streamflow projection in the Upper Colorado River Basin. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2012;16:3989–4007.

Kanamitsu M, DeHaan L. The added value index: a new metric to quantify the added value of regional models. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2011;116, doi:10.1029/2011jd015597.

Kay J, Deser C, Phillips A, Mai A, Hannay C, Strand G, et al. The Community Earth System Model (CESM) large ensemble project: a community resource for studying climate change in the presence of internal climate variability. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2014.

Kendon EJ, Roberts NM, Fowler HJ, Roberts MJ, Chan SC, Senior CA. Heavier summer downpours with climate change revealed by weather forecast resolution model. Nat Clim Chang. 2014;4:570–6. doi:10.1038/nclimate2258.

Kirchner J. Getting the right answers for the wrong reasons. Water Resour Res. 2006;42. doi:10.1029/2005wr004362

Knutti R. The end of model democracy? Clim Chang. 2010;102:395–404.

Knutti R, Sedláček J. Robustness and uncertainties in the new CMIP5 climate model projections. Nat Clim Chang. 2013;3:369–73.

Knutti R, Furrer R, Tebaldi C, Cermak J, Meehl GA. Challenges in combining projections from multiple climate models. J Clim. 2010;23:2739–58.

Knutti R, Masson D, Gettelman A. Climate model genealogy: generation CMIP5 and how we got there. Geophys Res Lett. 2013;40:1194–9.

Koster RD et al. The second phase of the global land-atmosphere coupling experiment: soil moisture contributions to subseasonal forecast skill. J Hydrometeorol. 2011;12:805–22. doi:10.1175/2011jhm1365.1.

Lempert RJ. Shaping the next one hundred years: new methods for quantitative, long-term policy analysis. 2003;0833034855.

Lempert R, Nakicenovic N, Sarewitz D, Schlesinger M. Characterizing climate-change uncertainties for decision-makers—an editorial essay. Clim Chang. 2004;65:1–9. doi:10.1023/B:CLIM.0000037561.75281.b3.

Liepert BG, Previdi M. Inter-model variability and biases of the global water cycle in CMIP3 coupled climate models. Environ Res Lett. 2012;7. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/1/014006.

Lofgren BM, Gronewold AD, Acciaioli A, Cherry J, Steiner A, Watkins D. Methodological approaches to projecting the hydrologic impacts of climate change. Earth Interact. 2013;17:19. doi:10.1175/2013ei000532.1.

Masson D, Knutti R. Climate model genealogy. Geophys Res Lett. 2011;38.

Maxwell RM, Kollet SJ. Interdependence of groundwater dynamics and land-energy feedbacks under climate change. Nat Geosci. 2008;1:665–9. doi:10.1038/ngeo315.

Mearns L, Sain S, Leung L, Bukovsky M, McGinnis S, Biner S, et al. Climate change projections of the North American regional climate change assessment program (NARCCAP). Clim Chang. 2013;120:965–75.

Meehl GA, Covey C, McAvaney B, Latif M, Stouffer RJ. Overview of the coupled model intercomparison project. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2005;86:89–93.

Mendoza P, Clark MP, Mizukami N, Newman AJ, Barlage M, Gutmann E, et al. Effects of hydrologic model choice and calibration on the portrayal of climate change impacts. J Hydrometeorol. 2014 (under review)

Mendoza PA, Clark MP, Mizukami N, Newman AJ, Barlage M, Gutmann ED, et al. Effects of hydrologic model choice and calibration on the portrayal of climate change impacts. J Hydrometeorol. 2015;16:762–80.

Miller WP, Butler RA, Piechota T, Prairie J, Grantz K, DeRosa G. Water management decisions using multiple hydrologic models within the San Juan River basin under changing climate conditions. J Water Resour Plan Manag. 2012;138:412–20.

Milly P, Dunne KA. On the hydrologic adjustment of climate-model projections: the potential pitfall of potential evapotranspiration. Earth Interact. 2011;15:1–14.

Milly P, Betancourt J, Falkenmark M, Hirsch RM, Kundzewicz ZW, Lettenmaier DP, et al. Stationarity is dead: whither water management? Science. 2008;319:573–4.

Mizukami N, Clark MP, Gutmann E, Mendoza PA, Newman AJ, Nijssen B, et al. Implications of the methodological choices for hydrologic portrayals of climate change over the contiguous United States: statistically downscaled forcing data and hydrologic models. J Hydrometeorol. 2015. doi:10.1175/JHM-D-14-0187.1.

Moser SC, Dilling L. Making climate hot—communicating the urgency and challenge of global climate change. Environment. 2004;46:32–46.

Mote PW, Hamlet AF, Clark MP, Lettenmaier DP. Declining mountain snowpack in western North America*. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2005;86:39–49.

Mote P, Brekke L, Duffy PB, Maurer E. Guidelines for constructing climate scenarios. Eos, Trans Am Geophys Union. 2011;92:257–8.

Murphy JM, Sexton DM, Barnett DN, Jones GS, Webb MJ, Collins M, et al. Quantification of modelling uncertainties in a large ensemble of climate change simulations. Nature. 2004;430:768–72.

Murphy JM, Booth BB, Collins M, Harris GR, Sexton DM, Webb MJ. A methodology for probabilistic predictions of regional climate change from perturbed physics ensembles. Philos Trans R Soc London A: Math Phys Eng Sci. 2007;365:1993–2028.

Nazemi AA, Wheater HS. Assessing the vulnerability of water supply to changing streamflow conditions. Eos, Trans Am Geophys Union. 2014;95:288.

Nazemi A, Wheater HS, Chun KP, Elshorbagy A. A stochastic reconstruction framework for analysis of water resource system vulnerability to climate-induced changes in river flow regime. Water Resour Res. 2013;49:291–305. doi:10.1029/2012wr012755.

Pathak CS, Teegavarapu RS, Olson C, Singh A, Lal AW, Polatel C, et al. Uncertainty analyses in hydrologic/hydraulic modeling: challenges and proposed resolutions. J Hydrol Eng. 2015. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0001231.

Pidgeon N, Fischhoff B. The role of social and decision sciences in communicating uncertain climate risks. Nat Clim Chang. 2011;1:35–41. doi:10.1038/nclimate1080.

Poff NL, Brown CM, Grantham TE, Matthews JH, Palmer MA, Spence CM, et al. 2015 Operationalizing sustainable water management under future hydrologic uncertainty: eco-engineering decision scaling. Nat Clim Chang, in press.

Poulin A, Brissette F, Leconte R, Arsenault R, Malo J-S. Uncertainty of hydrological modelling in climate change impact studies in a Canadian, snow-dominated river basin. J Hydrol. 2011;409:626–36.

Prudhomme C, Wilby RL, Crooks S, Kay AL, Reynard NS. Scenario-neutral approach to climate change impact studies: application to flood risk. J Hydrol. 2010;390:198–209. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.06.043.

Prudhomme C, Giuntoli I, Robinson EL, Clark DB, Arnell NW, Dankers R, et al. Hydrological droughts in the 21st century, hotspots and uncertainties from a global multimodel ensemble experiment. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:3262–7.

Racherla PN, Shindell DT, Faluvegi GS. The added value to global model projections of climate change by dynamical downscaling: a case study over the continental US using the GISS-ModelE2 and WRF models. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2012;117. doi:10.1029/2012jd018091.

Rasmussen R, Ikeda K, Liu CH, Gochis D, Clark MP, Dai A, et al. Climate change impacts on the water balance of the Colorado headwaters: high-resolution regional climate model simulations. J Hydrometeorol. 2014. doi:10.1175/JHM-D-13-0118.1.

Roderick ML, Sun F, Lim WH, Farquhar GD. A general framework for understanding the response of the water cycle to global warming over land and ocean. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2014;18:1575–89.

Rogelj J, Meinshausen M, Knutti R. Global warming under old and new scenarios using IPCC climate sensitivity range estimates. Nat Clim Chang. 2012;2:248–53.

Rupp DE, Abatzoglou JT, Hegewisch KC, Mote PW. Evaluation of CMIP5 20th century climate simulations for the Pacific Northwest USA. J Geophys Res: Atmos. 2013;118:10,884–810,906.

Samaniego L, Kumar R, Attinger S. Multiscale parameter regionalization of a grid-based hydrologic model at the mesoscale. Water Resour Res. 2010;46.

Sanderson BM, Knutti R, Caldwell P. Addressing interdependency in a multi-model ensemble by interpolation of model properties. J Clim. 2015.

Schewe J et al. Multimodel assessment of water scarcity under climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:3245–50. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222460110.

Sheffield J, Wood EF, Roderick ML. Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature. 2012;491:435–8.

Stainforth DA, Aina T, Christensen C, Collins M, Faull N, Frame DJ, et al. Uncertainty in predictions of the climate response to rising levels of greenhouse gases. Nature. 2005;433:403–6.

Stakhiv EZ. Pragmatic approaches for water management under climate change uncertainty. J Am Water Resour Assoc. 2011;47:1183–96. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2011.00589.x.

Steinschneider S, Brown C. A semiparametric multivariate, multisite weather generator with low-frequency variability for use in climate risk assessments. Water Resour Res. 2013;49:7205–20. doi:10.1002/wrcr.20528.

Tebaldi C, Knutti R. The use of the multi-model ensemble in probabilistic climate projections. Philos Trans R Soc London A: Math Phys Eng Sci. 2007;365:2053–75.

Tebaldi C, Smith RL, Nychka D, Mearns LO. Quantifying uncertainty in projections of regional climate change: a Bayesian approach to the analysis of multimodel ensembles. J Clim. 2005;18:1524–40.

Teutschbein C, Seibert J. Bias correction of regional climate model simulations for hydrological climate-change impact studies: review and evaluation of different methods. J Hydrol. 2012;456:12–29.

Vano JA, Lettenmaier DP. A sensitivity-based approach to evaluating future changes in Colorado River discharge. Clim Chang. 2014;122:621–34.

Vano JA, Udall B, Cayan DR, Overpeck JT, Brekke LD, Das T, et al. Understanding uncertainties in future Colorado River streamflow. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2014;95:59–78.

Vano JA, Kim JB, Rupp DE, Mote PW. Selecting climate change scenarios using impact-relevant sensitivities. Geophys Res Lett. 2015;42:5516–25.

Vaze J, Post D, Chiew F, Perraud J-M, Viney N, Teng J. Climate non-stationarity—validity of calibrated rainfall–runoff models for use in climate change studies. J Hydrol. 2010;394:447–57.

Velázquez J, Schmid J, Ricard S, Muerth M, Gauvin St-Denis B, Minville M, et al. An ensemble approach to assess hydrological models’ contribution to uncertainties in the analysis of climate change impact on water resources. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci. 2013;17:565–78.

Wilby RL. Uncertainty in water resource model parameters used for climate change impact assessment. Hydrol Process. 2005;19:3201–19.

Wilby R. Evaluating climate model outputs for hydrological applications. Hydrol Sci J–J des Sci Hydrol. 2010;55:1090–3.

Wilby RL, Dessai S. Robust adaptation to climate change. Weather. 2010;65:180–5.

Wilby RL, Harris I. A framework for assessing uncertainties in climate change impacts: low‐flow scenarios for the River Thames, UK. Water Resour Res. 2006;42.

Wilby RL, Fowler HJ. Regional climate downscaling. In: Fung CF, Lopez A, New M editors. Modelling the Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing; 2010. p 34.

Wilby RL, Dawson CW, Murphy C, O’Connor P, Hawkins E. The Statistical DownScaling Model-Decision Centric (SDSM-DC): conceptual basis and applications. Clim Res. 2014;61:259–76. doi:10.3354/cr01254.

Wilcke A, Barring L. Selecting regional climate scenarios for impact modelling studies. Environ Model Softw. 2016;78:191–201.

Yang Z, Arritt RW. Tests of a perturbed physics ensemble approach for regional climate modeling. J Clim. 2002;15:2881–96.

Yates D, Miller K, Wilby RJL, Kaatz L. A decision-centric approach to climate adaptation options appraisal. Clim Risk Manag. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.crm.2015.06.001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Hydrologic Impact (Society and Water Cycles)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, M.P., Wilby, R.L., Gutmann, E.D. et al. Characterizing Uncertainty of the Hydrologic Impacts of Climate Change. Curr Clim Change Rep 2, 55–64 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-016-0034-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-016-0034-x