Abstract

Purpose

Post-finasteride syndrome (PFS) has been reported in a subset of patients treated with finasteride (an inhibitor of the enzyme 5alpha-reductase) for androgenetic alopecia. These patients showed, despite the suspension of the treatment, a variety of persistent symptoms, like sexual dysfunction and cognitive and psychological disorders, including depression. A growing body of literature highlights the relevance of the gut microbiota-brain axis in human health and disease. For instance, alterations in gut microbiota composition have been reported in patients with major depressive disorder. Therefore, we have here analyzed the gut microbiota composition in PFS patients in comparison with a healthy cohort.

Methods

Fecal microbiota of 23 PFS patients was analyzed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and compared with that reported in ten healthy male subjects.

Results

Sexual dysfunction, psychological and cognitive complaints, muscular problems, and physical alterations symptoms were reported in more than half of the PFS patients at the moment of sample collection. The quality sequence check revealed a low library depth for two fecal samples. Therefore, the gut microbiota analyses were conducted on 21 patients. The α-diversity was significantly lower in PFS group, showing a reduction of richness and diversity of gut microbiota structure. Moreover, when visualizing β-diversity, a clustering effect was found in the gut microbiota of a subset of PFS subjects, which was also characterized by a reduction in Faecalibacterium spp. and Ruminococcaceae UCG-005, while Alloprevotella and Odoribacter spp were increased compared to healthy control.

Conclusion

Gut microbiota population is altered in PFS patients, suggesting that it might represent a diagnostic marker and a possible therapeutic target for this syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The post-finasteride syndrome (PFS) is an emerging clinical problem observed in a subset of patients treated with finasteride for androgenetic alopecia. These patients, despite the suspension of treatment, reported a variety of persistent symptoms, including sexual dysfunction, psychological complaints, muscular problems, physical alterations, and cognitive complaints [1, 2]. Examples of them are feeling a lack of connection between the brain and penis, loss of libido and sexual drive, difficulty in achieving erection, genital numbness or paresthesia, depression, reduction in self-confidence, decreased initiative and difficulty in concentration, forgetfulness or loss of short-term memory, irritability, suicidal thoughts, anxiety, panic attacks, sleep problems, muscular stiffness and cramps, tremors, chronic fatigue, joint pain, and muscular ache [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

Finasteride is an inhibitor of the 5alpha-reductase (5α-R). This enzyme represents a key step in the conversion of neuroactive steroids, such as progesterone (PROG) and testosterone (T) into their reduced metabolites, such as dihydroprogesterone (DHP), tetrahydroprogesterone (THP), and isopregnanolone in case of PROG and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), 5α-androstane-3α,17β-diol (3α-diol) and 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol (3β-diol) in case of T. These neuroactive metabolites exert an important physiological control of the nervous functions by activating classical and non-classical steroid receptors [23, 24]. In agreement, alterations of their levels have been reported in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [25,26,27] as well as in PFS patients [14, 21, 22]. We have recently studied the PFS in a pre-clinical rat model, describing alterations of neuroactive steroid levels in brain areas [28] as well as depressive-like behavior coupled with cellular and molecular markers, such as a decrease in the neurogenesis and increased neuroinflammation and reactive gliosis, one month after drug treatment interruption [29]. Interestingly, the composition of the microbiota was altered in this experimental setup, with a decrease in Ruminococcaceae family and Oscillospira and Lachnospira genus [29]. There is a growing body of literature showing the relevance of the gut microbiota-brain axis both in human health and disease [30,31,32]. In particular, alterations in gut microbiota composition have been reported in patients with major depressive disorder [33,34,35] as well as in animal models of depression [36].

In this study, we analyze the composition of the fecal microbiota in PFS patients in comparison with a healthy cohort.

Materials and methods

Study design and sample preparation

PFS patients were recruited through the Italian finasteride side effects network. Twenty-three healthy men, aged 25–51 years who reported persistent sexual and mental health side effects after the use of 1–1.25 mg daily of finasteride (i.e., Propecia, Proscar, or generic finasteride) for androgenetic alopecia, were considered in the case group. Only subjects who had suspended finasteride treatment at least 3 months earlier, had not used drugs known to potentially interfere with microbiome analysis, and were not affected by psychiatric disorders or sexual dysfunction before finasteride use, were included. The study procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Milano-Bicocca Monza-Italy, (protocol number 434/2018) and the participating subjects provided their written informed consent before enrollment. A questionnaire was used to evaluate both the absence of PFS signs and symptoms before the finasteride treatment and the presence of this accompanying signs and symptoms after the drug treatment. Although not validated, it represents the only available tool to systematically collect information on patient conditions and to assess the features of PFS. The same questionnaire was used in our previous observations on PFS patients [1, 2, 14, 21, 22]. The questionnaire was filled by the patient himself only after the description of the study design to the patient, in order to limit selection and recall bias. The patients answered to the following questions (Q) with never/sometimes/often/always: (Q1) Decreased self-confidence; (Q2) Decline of emotional verve, initiative, and desire to do; (Q3) Difficulty concentrating and focusing (brain fog); (Q4) Mental confusion; (Q5) Forgetfulness or loss of short-term memory; (Q6) Losing train of thought or reasoning; (Q7) Slurred speech or stumbling over words; (Q8) Irritability or easily flying into a rage; (Q9) Nervousness, agitation, and inner restlessness; (Q10) Depression, hopelessness, and feelings of worthlessness; (Q11) Suicidal thoughts; (Q12) Anxiety; (Q13) Panic attacks; (Q14) Sleep problems; (Q15) Loss of libido and sexual desire; Q16) Difficulty in achieving an erection; (Q17) Feeling of a lack of connection between the brain and the penis; (Q18) Genital numbness or paresthesia; (Q19) Feeling tinglings or pinpricks; (Q20) Tics and muscle spasms; (Q21) Tremors; (Q22) Involuntary muscle tension and contraction; (Q23) Dizziness; (Q24) Headache and migraine; (Q25) Chronic fatigue, weakness; (Q26) Joint pain and muscular ache; (Q27) Decreased body temperature; and (Q28) Photophobia and other visual problems.

All participants were Caucasian ethnicity adhering to Mediterranean diet and did not show any co-morbidities before and after finasteride treatment. No drug treatment was reported after finasteride treatment, including prebiotics, probiotics, and antibiotics. In addition, neither constipation nor Irritable Bowel Syndrome was registered.

The fecal gut microbiota composition in PFS patients was compared to healthy cohort. Stool samples were home collected and stored at − 80 °C until use. The raw sequences of the healthy cohort (ten male subjects) are available in Borgo and collaborators [37] under BioProject PRJNA401981. PFS patients and Healthy subjects were ethnicity, sex, diet, and BMI matched.

Bacterial DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

Total bacterial DNA was extracted from 200 mg of stool samples using Dneasy Powersoil Pro Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instruction. 16S rRNA gene amplicon libraries were performed with a two-step barcoding approach according to Diviccaro et al. [34].

Briefly, the 16S rRNA gene was initially amplified by interest-specific primers targeting V3 (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and V4 (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) regions coupled with overhang adapters. The reaction was carried out in 25 µl volumes containing 6 ng/µl microbial DNA, 1 µM of each primer, and 2 × KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche).

The following PCR program was used: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 25 cycles consisting of denaturation (95 °C for 30 s), annealing (55 °C for 30 s), and extension (72 °C for 30 s), and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis for quantity and quality. Expected size of the products after Amplicon PCR step is about 550 bp.

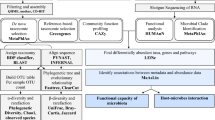

DNA samples resulting from PCR step were amplified with dual-index primers using Nextera Xt Index Kit V2 Set A (Illumina). Library concentration and exact product size were measured using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer System (Agilent). A 20 nM pooled library and a PhiX control v3 (20 nM) (Illumina) were mixed with 0.2 N fresh NaOH to produce the final concentration at 10 pM each and injected on a Miseq Reagent Nano Kit V2 500 Cycles for obtaining a paired-end 2 × 150 bp sequencing. Sequencing was performed at the IEO Genomic Unit. Fastq files were checked for quality using FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and data analysis was performed using QIIME2 suite. Denoising was performed using the deblur denoise-16S workflow, setting the trim length to 245 bp. Sequences from the PFS patients (n = 23) were analyzed together with a healthy dataset (n = 10) matched by sex (male) and BMI (normal), by merging the output feature table and representative sequences from deblur denoising step. Phylogenetic tree reconstruction was performed on the merged table and sequences by fragment insertion using SEPP, with the SILVA 128 database used as reference. Core diversity analysis was performed with the core-metrics-phylogenetic pipeline, using the output feature table from deblur and tree from SEPP, with the rarefaction depth set to 1336 reads. Taxonomic classification of sub-OTU sequences identified by deblur was performed using the sample-classifier pipeline, by training a Naive Bayes classifier on V3–V4-trimmed 16S sequences from the SILVA 132 database.

Statistical analysis

Sample biodiversity (i.e., α-diversity) was evaluated according to different microbial diversity metrics including Chao1, Shannon index, Evenness, Observed OTUs, and Faith’s phylogenetic distance. Inter-sample diversity (i.e., β-diversity) was calculated by using both weighted and unweighted UniFrac and Bray–Curtis distance metrics. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was performed using build-in functions in QIIME2. Groups significance, according to experimental design, was calculated by Kruskal–Wallis test for alpha metrics vectors, whereas PERMANOVA test for beta-metrics distance matrices. Statistical significance was calculated using a Mann–Whitney test for comparison within two groups or Kruskal -Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison correction within more than two groups. P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), and P < 0.001 (***) are regarded as statistically significant.

Results

General data of the PFS patients at the clinical evaluation

Twenty-three PFS men vs healthy cohort (ten male subjects) were evaluated. Table 1 reports anthropometric data (weight, height, and body mass index) and age at the time of enrollment. For PFS patients, the mean of treatment duration was 1176 days. The interval between finasteride withdrawal and clinical evaluation was very wide (range 433–7111 days, median 2465).

No statistical significant differences vs controls were found for height (p = 0.25), weight (p = 0.34), and BMI (p = 0.91) with the exception of age (p = 0.002). However, as well reported in literature, the gut microbiota composition is only affected during infancy and at old ages, while it is stable during the adult age [38]. Therefore, we have considered these patients for the present study.

Frequency of the symptoms pre-finasteride and post-finasteride was self-reported by the patients filling a questionnaire at the moment of the gut microbiota evaluations. More of the 50% of PFS patients considered in our study never reported symptoms related with sexual dysfunction, psychological complaints, muscular problems, physical alterations, and cognitive complaints before finasteride treatment. The only exceptions were represented by irritability/easily flying into a rage (Q8) or anxiety (Q12), which were sometimes/often (69.6% and 65.2%, respectively) reported also before treatment. Most of the symptoms were sometimes/often/always reported by more of the 50% of PFS patients at the moment of the gut microbiota evaluations. Panic attacks (Q13), feeling tinglings/pinpricks (Q19), tremors (Q21), dizziness (Q23), or headache (Q24) were never reported by the majority of the PFS patients, instead (Q13 and 24: 52.2%; Q19 and 21: 56.5%; Q23: 69.6%).

Gut microbiota structure in PFS patients

The microbiota community structure of PFS subjects was examined in comparison to healthy cohort by α-diversity (within-sample diversity) metrics. Two PFS patients (i.e., the number 9 and 18 in Table 1) were characterized by a very low NGS library depth; therefore, we decided to remove them from gut microbiota evaluation. Significant differences among community richness were observed, as estimated by Chao1 (p = 0.047) index, showing a different gut microbiota structure in PFS subjects (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic diversity (Faith’s PD), which takes into consideration the phylogeny of microbes to estimate diversity across a tree, indicates a different richness and evenness (p = 0.047) (Fig. 1). No significant differences in diversity were observed between PFS and healthy subjects (Observed-OTUs, p = 0.40; Shannon, p = 0.75; Simpson, p = 0.89) (Fig. 1).

For gaining a more comprehensive view of diversity, we applied three different ß-diversity (between sample diversity comparisons) metrics visualized by Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) (Fig. 2). PCoA is plotted for representing the microbial community compositional differences between PFS and healthy cohorts. The bacterial composition of these gut microbiota communities clustered according to the grouping. Unweighted UniFrac distance showed a significant clustering based on differences in low-abundance features (p = 0.001). The same clustering is partially confirmed by the weighted UniFrac distance (p = 0.05), underlining the significant differences in terms of microbial composition. In addition, we calculated the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity within PFS and healthy to quantify community similarity of the same sample type (p = 0.001). Community dissimilarity between samples within each group was smaller than dissimilarity between samples from different groups.

Beta-diversity analysis revealed two different sub-clusters in 21 PFS subjects. Unweighted UniFrac distance (a) showed significant separation for PFS-A and healthy subjects (p = 0.001), between PFS-B and healthy cohorts (p = 0.001), and within PFS subjects (PFS-A vs PFS-B; p = 0.001). Weighted UniFrac distance (b) showed a significant separation for PFS-A and healthy subjects (p = 0.001), and for PFS-A and PFS-B (p = 0.001), but no significant separation between PFS-B (p = 0.37) and healthy cohorts was detected. Bray–Curtis dissimilarity (c) showed a significant clustering (p = 0.001) for healthy and PFS sub-clusters

Interestingly, the analysis of the ß-diversity distinguishes two different sub-clusters within PFS patients (Fig. 2). In particular, the discrimination between PFS patients and healthy groups is driven by the sub-cluster A (Unweighted UniFrac, p = 0.001; Weighted UniFrac, p = 0.001; Bray–Curtis, p = 0.001), rather than the sub-cluster B (Unweighted UniFrac, p = 0.001; Weighted UniFrac, p = 0.37, Bray–Curtis metrics, p = 0.001) (Fig. 2). A strong separation was found for PFS-A and PFS-B in all tested ß-diversity metrics used (Unweighted UniFrac, p = 0.001; Weighted UniFrac, p = 0.001; Bray–Curtis, p = 0.001).

Overall, across the α- and ß-diversity metrics used, PFS group showed a significant reduction of richness, diversity, and composition (low-abundance features), indicating a different gut microbiota structure. Furthermore, the analysis of ß-diversity highlighted two distinct microbial clusters in PFS subjects, with PFS-A more distant to healthy cluster. To gain insight into the microbial differences in PFS patients, we applied multivariate analysis in order to find possible associations between gut microbiota composition, cohort characteristics, and clinical evaluation. No significant association was detected, except the days from suspension of finasteride treatment that seems to be more associated with PFS-A microbiota, even if not statistically significant (p = 0.06, data not shown).

Gut microbiota composition in PFS patients

In addition to the microbiota structure analysis, we also investigated the microbiota composition. As expected, the most relatively abundant phyla in healthy and PFS subjects were Firmicutes (mean ± SD; Healthy: 45.4 ± 7.0; PFS: 57.6 ± 17.3; p = 0.09) and Bacteroidetes (Healthy: 40.4 ± 15.0; PFS: 34.8 ± 17.3; p = 0.40) (Fig. 3a). PFS group was significantly depleted in Proteobacteria (Healthy: 10.2 ± 15.6; PFS: 4.5 ± 11.3; p = 0.009) and Actinobacteria (Healthy: 22.6 ± 2.5; PFS: 4.5 ± 3.5; p = 0.0003) (Fig. 3a). Among the most relatively abundant families, we found Acidaminococcaceae (Healthy: 5.5 ± 10.0; PFS: 4.5 ± 4.8; p = 0.04), Enterobacteriaceae (Healthy: 7.3 ± 13; PFS: 2.9 ± 11.0; p = 0.005), Bifidobacteriaceae (Healthy: 15.2 ± 2.2; PFS: 12.3 ± 3.4; p = 0.005), Barnesiellaceae (Healthy: 1.5 ± 2.8; PFS: 0.3 ± 0.9; p = 0.001), Christensenellaceae (Healthy: 2.2 ± 2.6; PFS: 0.04 ± 0.1; p < 0.001), and Desulfovibrionaceae (Healthy: 1.8 ± 1.8; PFS: 0.02 ± 0.01; p < 0.001) to be significantly reduced in PFS patients (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, two families closely related to gut microbiota dysbiosis were found different, although not significantly present in PFS subjects in comparison to healthy: Prevotellaceae family (Healthy: 3.6 ± 6.0; PFS: 6.9 ± 10.2; p = 0.35) and Akkermansiaceae (Healthy: 1.1 ± 2.6; PFS: 0.5 ± 1.0; p = 0.11) (Fig. 4b). At genus level, the microbiota composition of PFS subjects was characterized by a significant reduction in Subdoligranulum (Healthy: 3.8 ± 2.7; PFS: 0.9 ± 1.7; p = 0.009), Phascolarctobacterium (Healthy: 4.3 ± 4.9; PFS: 2.6 ± 6.7; p = 0.009), Ruminococcaceae UCG-002 (Healthy: 4.2 ± 3.2; PFS: 0.12 ± 0.27; p < 0.0001), and Escherichia–Shigella (Healthy: 7.3 ± 13.2; PFS: 2.8 ± 10.8; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, Turicibacter (Healthy: 0.02 ± 0.04; PFS: 0.3 ± 0.5; p = 0.16) and Blautia (Healthy: 0.2 ± 0.1; PFS: 2.7 ± 4.2; p = 0.44), two genera described as related to depressive symptomology, were increased in PFS patients.

To determine whether the two sub-clusters of PFS patients identified have different gut microbiota composition, we analyzed their relative abundances at phylum, family, and genus levels. Sub-cluster A was significantly enriched in Firmicutes in comparison to B (p = 0.03) and healthy (p = 0.002), while Actinobacteria was more abundant in healthy than in sub-cluster A (p = 0.04) (Fig. 4a). The composition of Veillonellaceae family was different between healthy and sub-cluster A (p = 0.02), whereas Peptostreptococcaceae abundance was higher in sub-cluster A than in B (p = 0.03) (Fig. 4b). Subdoligranulum spp. (p = 0.007, p = 0.003), Lachnoclostridium spp. (p = 0.01, p = 0.0006), Bilophila spp. (p = 0.002, p = 0.0002) genera, and Christensenellaceae R7 group (p = 0.05, p = 0.0008) showed a higher abundance in healthy in comparison, respectively, to PFS-A and PFS-B. On the contrary, in comparison to healthy subjects, Faecalibacterium spp. (p = 0.02) and Ruminococcaceae UCG-005 (p = 0.02) were decreased only in sub-cluster A, while Alloprevotella (p = 0.03) and Odoribacter spp. (p = 0.02) were increased (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

Data here reported indicate for the first time that gut microbiota composition was altered in PFS patients. In particular, at the phylum level, we here reported a significant increase in Firmicutes and a decrease in Proteobacteria. Moreover, Acidaminococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Bifidobacteriaceae, Barnesiellaceae, Christensenellaceae, and Desulfovibrionaceae families were significantly decreased. Furthermore, at genus levels Subdoligranulum, Phascolarctobacterium, Ruminococcaceae UCG-002, and Escherichia–Shigella were reported to be significantly decreased in PFS patients. Thus, gut microbiota composition is altered in a court of patients who, despite finasteride suspension, report a persistent symptomatology, such as depression, sleep disturbance, and sexual dysfunction [1, 2]. As often observed, depression and insomnia are frequently associated [39, 40]. Indeed, as recently observed, alterations of gut microbiome have been reported in depressive disorders [41,42,43,44,45] as well as in circadian and sleep disturbance [46,47,48]. In addition, as mentioned above, PFS reported persistent sexual impairment, including feeling a lack of connection between the brain and penis, loss of libido and sex drive, difficulty in achieving an erection, genital numbness, or paresthesia [1, 2]. Indeed, as demonstrated in two different studies, PFS patients showed erectile dysfunction [13, 14]. In agreement with the present results, gut microbiota population is also altered in an experimental model of diabetic erectile dysfunction [49].

Interestingly, under β-diversity analysis, we reported two different sub-clusters of PFS patients significantly different from the healthy group used as control. No statistical differences between the two sub-clusters were observed in terms of age (p = 0.5262), BMI (p = 0.1927), finasteride treatment period (p = 0.817), suspension period (p = 0.126), and symptoms reported after finasteride suspension in the questionnaire (data not shown).

At the phylum, family, and genus levels, some gut microbiota populations were modified in the sub-cluster named A but not in B. For instance, at the genus level, Ruminococcaceae UCG-005 were significantly decreased in the sub-cluster A of the PFS patients analyzed. It is interesting to note that a similar decrease has been reported by us also in an experimental model of PFS. Indeed, male rats chronically treated with finasteride for 20 days revealed after one month of suspension a decrease of Ruminococcaceae [29]. In this context, it is important to highlight, that in agreement with the observation that depressed patients showed a decrease in Ruminococcaceae population [33] and Blautia spp.[50], PFS patients [13, 14] as well as experimental model of PFS [29] showed depressive symptomatology. Similarly, in agreement with the decrease observed in depressed patients [33, 42, 51], in the sub-cluster A of PFS patients, we also report a decrease in Veillonellaceae as well as Faecalibacterium spp. population.

The reduction of Faecalibacterium spp. has been suggested to be associated with gut dysbiosis and depressive disorders [52]. In addition, this genus is also an important producer of butyrate [53], a short-chain fatty acid which exerts an important role in the communication of gut microbiota and brain [54] and that recently has been proposed to exert a role in sleep modulation [55]. Thus, Faecalibacterium spp. might represent a possible target for a therapy aimed to restore gut microbiota alterations in PFS patients and possibly, on the basis of the existence of the gut microbiota-brain axis, also other symptoms observed in these patients. A relationship between gut microbiota population and steroid environment has been also proposed [45, 56, 57]. Indeed, gonadectomy and hormone replacement have a clear effect on gut bacteria in rodents [58,59,60,61,62,63], for instance, the changes observed in Ruminococcaceae after orchidectomy in mice [58]. Alteration in Ruminococcaceae also occurred in prostate cancer patients treated with oral androgen receptor axis-targeted therapies [64]. On this basis, it is possible to hypothesize that gut microbiota changes observed in PFS patients may be ascribed to the alteration of steroid environment. Indeed, alterations in the levels of 5α-reduced metabolites of PROG and T have been reported in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of PFS patients [14, 21, 22]. In addition, since as demonstrated in an experimental model of PFS, alteration of steroid environment also occurs in brain regions [28], the existence of a gut microbiota-brain axis [30,31,32] may also suggest a role by brain steroids. Finally, a possible contribution by intestinal steroid environment may be also hypothesized. Up to now, steroidogenic capacity in this compartment has not fully clarified. However, microbial species, such as Clostridium scindens, have the potentiality to convert glucocorticoids into androgens [65] and therefore may be potential target for the effect of finasteride. In addition, it has been recently demonstrated that type 1 5α-R is expressed in mouse cecum and colon with significant T and DHT levels in these rodent structures as well as in feces of healthy young adult men [66]. Moreover, both in PFS patients as well as in its experimental model [14, 21, 22, 28], finasteride affects the levels of THP, thus a steroid able to interact with GABA-A receptor [24]. In this context, it is important to remember that some members of human microbiota (i.e., Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp.) encode for genes involved in GABA production, suggesting a microbial participation in the production of this neurotransmitter within the gut [67, 68]. Indeed, GABA-A receptors have been recently identified in the mouse colon [69, 70]. Interestingly, we recently observed that rat colon expresses steroidogenic capability and, in particular, an high production of a T metabolite, such as the 3α-diol [71]. It is important to note that this androgen metabolite, like THP, is able to interact with GABA-A receptors [72] and its levels are affected in PFS patients as well as in its experimental model [14, 21, 22, 28]. This may further support the hypothesis of a role of steroids interacting with GABA-A receptors in the pathogenesis of PFS.

In conclusion, data here reported indicate for the first time that gut microbiota population is altered in PFS patients. With all the limitations represented by the small cohort here considered for this emerging and rare syndrome, these results suggest that gut microbiota composition might represent a diagnostic marker and a possible target for a therapeutic strategy aimed to counteract the important symptomatology occurring in these patients.

Data availability

Datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Diviccaro S, Melcangi RC, Giatti S (2020) Post-finasteride syndrome: an emerging clinical problem. Neurobiol Stress 100209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100209

Giatti S, Diviccaro S, Panzica G, Melcangi RC (2018) Post-finasteride syndrome and post-SSRI sexual dysfunction: two sides of the same coin? Endocrine 2(61):180–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-018-1593-5

Gur S, Kadowitz PJ, Hellstrom WJ (2013) Effects of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors on erectile function, sexual desire and ejaculation. Expert Opin Drug Saf 12(1):81–90. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2013.742885

Corona G, Rastrelli G, Maseroli E, Balercia G, Sforza A, Forti G, Mannucci E, Maggi M (2012) Inhibitors of 5alpha-reductase-related side effects in patients seeking medical care for sexual dysfunction. J Endocrinol Invest 35(10):915–920. https://doi.org/10.3275/8510

Traish AM, Melcangi RC, Bortolato M, Garcia-Segura LM, Zitzmann M (2015) Adverse effects of 5alpha-reductase inhibitors: what do we know, don't know, and need to know? Rev Endocr Metab Disord 16:177–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-015-9319-y

Traish AM, Hassani J, Guay AT, Zitzmann M, Hansen ML (2011) Adverse side effects of 5alpha-reductase inhibitors therapy: persistent diminished libido and erectile dysfunction and depression in a subset of patients. J Sex Med 8(3):872–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02157.x

Irwig MS, Kolukula S (2011) Persistent sexual side effects of finasteride for male pattern hair loss. J Sex Med 8(6):1747–1753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02255.x

Irwig MS (2012) Persistent sexual side effects of finasteride: could they be permanent? J Sex Med 9(11):2927–2932. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02846.x

Guo M, Heran B, Flannigan R, Kezouh A, Etminan M (2016) Persistent sexual dysfunction with finasteride 1 mg taken for hair loss. Pharmacotherapy 36(11):1180–1184. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1837

Kiguradze T, Temps WH, Yarnold PR, Cashy J, Brannigan RE, Nardone B, Micali G, West DP, Belknap SM (2017) Persistent erectile dysfunction in men exposed to the 5alpha-reductase inhibitors, finasteride, or dutasteride. PeerJ 5:e3020. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3020

Chiriaco G, Cauci S, Mazzon G, Trombetta C (2016) An observational retrospective evaluation of 79 young men with long-term adverse effects after use of finasteride against androgenetic alopecia. Andrology 4(2):245–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12147

Ganzer CA, Jacobs AR, Iqbal F (2015) Persistent sexual, emotional, and cognitive impairment post-finasteride: a survey of men reporting symptoms. Am J Mens Health 9(3):222–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988314538445

Basaria S, Jasuja R, Huang G, Wharton W, Pan H, Pencina K, Li Z, Travison TG, Bhawan J, Gonthier R, Labrie F, Dury AY, Serra C, Papazian A, O'Leary M, Amr S, Storer TW, Stern E, Bhasin S (2016) Characteristics of men who report persistent sexual symptoms after finasteride use for hair loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101(12):4669–4680. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-2726

Melcangi RC, Santi D, Spezzano R, Grimoldi M, Tabacchi T, Fusco ML, Diviccaro S, Giatti S, Carra G, Caruso D, Simoni M, Cavaletti G (2017) Neuroactive steroid levels and psychiatric and andrological features in post-finasteride patients. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 171:229–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.04.003

Ali AK, Heran BS, Etminan M (2015) Persistent sexual dysfunction and suicidal ideation in young men treated with low-dose finasteride: a pharmacovigilance study. Pharmacotherapy 35(7):687–695. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1612

Fertig R, Shapiro J, Bergfeld W, Tosti A (2017) Investigation of the plausibility of 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor syndrome. Skin Appendage Disord 2(3–4):120–129. https://doi.org/10.1159/000450617

Irwig MS (2012) Depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts among former users of finasteride with persistent sexual side effects. J Clin Psychiatry 73(9):1220–1223. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12m07887

Rahimi-Ardabili B, Pourandarjani R, Habibollahi P, Mualeki A (2006) Finasteride induced depression: a prospective study. BMC Clin Pharmacol 6:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6904-6-7

Altomare G, Capella GL (2002) Depression circumstantially related to the administration of finasteride for androgenetic alopecia. J Dermatol 29(10):665–669

Hogan C, Le Noury J, Healy D, Mangin D (2014) One hundred and twenty cases of enduring sexual dysfunction following treatment. Int J Risk Saf Med 26(2):109–116. https://doi.org/10.3233/jrs-140617

Melcangi RC, Caruso D, Abbiati F, Giatti S, Calabrese D, Piazza F, Cavaletti G (2013) Neuroactive steroid levels are modified in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of post-finasteride patients showing persistent sexual side effects and anxious/depressive symptomatology. J Sex Med 10(10):2598–2603. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12269

Caruso D, Abbiati F, Giatti S, Romano S, Fusco L, Cavaletti G, Melcangi RC (2015) Patients treated for male pattern hair with finasteride show, after discontinuation of the drug, altered levels of neuroactive steroids in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 146:74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.03.012

Giatti S, Garcia-Segura LM, Barreto GE, Melcangi RC (2019) Neuroactive steroids, neurosteroidogenesis and sex. Prog Neurobiol 176:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.06.007

Melcangi RC, Garcia-Segura LM, Mensah-Nyagan AG (2008) Neuroactive steroids: state of the art and new perspectives. Cell Mol Life Sci 65(5):777–797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-007-7403-5

Melcangi RC, Giatti S, Calabrese D, Pesaresi M, Cermenati G, Mitro N, Viviani B, Garcia-Segura LM, Caruso D (2014) Levels and actions of progesterone and its metabolites in the nervous system during physiological and pathological conditions. Prog Neurobiol 113:56–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.07.006

Melcangi RC, Giatti S, Garcia-Segura LM (2016) Levels and actions of neuroactive steroids in the nervous system under physiological and pathological conditions: sex-specific features. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 67:25–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.023

Giatti S, Diviccaro S, Serafini MM, Caruso D, Garcia-Segura LM, Viviani B, Melcangi RC (2019) Sex differences in steroid levels and steroidogenesis in the nervous system: Physiopathological role. Front Neuroendocrinol 100804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100804

Giatti S, Foglio B, Romano S, Pesaresi M, Panzica G, Garcia-Segura LM, Caruso D, Melcangi RC (2016) Effects of subchronic finasteride treatment and withdrawal on neuroactive steroid levels and their receptors in the male rat brain. Neuroendocrinology 103(6):746–757. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442982

Diviccaro S, Giatti S, Borgo F, Barcella M, Borghi E, Trejo JL, Garcia-Segura LM, Melcangi RC (2019) Treatment of male rats with finasteride, an inhibitor of 5alpha-reductase enzyme, induces long-lasting effects on depressive-like behavior, hippocampal neurogenesis, neuroinflammation and gut microbiota composition. Psychoneuroendocrinology 99:206–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.09.021

Sharon G, Sampson TR, Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK (2016) The central nervous system and the gut microbiome. Cell 167(4):915–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.027

Lerner A, Neidhofer S, Matthias T (2017) The gut microbiome feelings of the brain: a perspective for non-microbiologists. Microorganisms 5(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms5040066

Mayer EA (2011) Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Neurosci 12(8):453–466. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3071

Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, Mao H, Ma Z, Yin Y, Wang W, Tang W, Tan Z, Shi J, Li L, Ruan B (2015) Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun 48:186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016

Naseribafrouei A, Hestad K, Avershina E, Sekelja M, Linlokken A, Wilson R, Rudi K (2014) Correlation between the human fecal microbiota and depression. Neurogastroenterol Motil 26(8):1155–1162. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12378

Lin P, Ding B, Feng C, Yin S, Zhang T, Qi X, Lv H, Guo X, Dong K, Zhu Y, Li Q (2017) Prevotella and Klebsiella proportions in fecal microbial communities are potential characteristic parameters for patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 207:300–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.051

Yu M, Jia H, Zhou C, Yang Y, Zhao Y, Yang M, Zou Z (2017) Variations in gut microbiota and fecal metabolic phenotype associated with depression by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and LC/MS-based metabolomics. J Pharm Biomed Anal 138:231–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2017.02.008

Borgo F, Garbossa S, Riva A, Severgnini M, Luigiano C, Benetti A, Pontiroli AE, Morace G, Borghi E (2018) Body mass index and sex affect diverse microbial niches within the gut. Front Microbiol 9:213. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00213

Mehta RS, Abu-Ali GS, Drew DA, Lloyd-Price J, Subramanian A, Lochhead P, Joshi AD, Ivey KL, Khalili H, Brown GT, DuLong C, Song M, Nguyen LH, Mallick H, Rimm EB, Izard J, Huttenhower C, Chan AT (2018) Stability of the human faecal microbiome in a cohort of adult men. Nat Microbiol 3(3):347–355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-017-0096-0

Seow LS, Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Chong SA (2016) Sleep disturbance among people with major depressive disorders (MDD) in Singapore. J Ment Health 25(6):492–499. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1124390

Staner L (2010) Comorbidity of insomnia and depression. Sleep Med Rev 14(1):35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2009.09.003

Horne R, Foster JA (2018) Metabolic and microbiota measures as peripheral biomarkers in major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry 9:513. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00513

Liu Y, Zhang L, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhang J, Jiang R, Wang X, Wang K, Liu Z, Xia Z, Xu Z, Nie Y, Lv X, Wu X, Zhu H, Duan L (2016) Similar fecal microbiota signatures in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and patients with depression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 14(11):1602–1611 e1605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.033

Liang S, Wu X, Hu X, Wang T, Jin F (2018) Recognizing depression from the microbiota(-)gut(-)brain axis. Int J Mol Sci 19(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19061592

Winter G, Hart RA, Charlesworth RPG, Sharpley CF (2018) Gut microbiome and depression: what we know and what we need to know. Rev Neurosci 29(6):629–643. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2017-0072

Jaggar M, Rea K, Spichak S, Dinan TG, Cryan JF (2020) You've got male: sex and the microbiota-gut-brain axis across the lifespan. Front Neuroendocrinol 56:100815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100815

Li Y, Hao Y, Fan F, Zhang B (2018) The role of microbiome in insomnia, circadian disturbance and depression. Front Psychiatry 9:669. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00669

Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Green SJ, Mutlu E, Engen P, Vitaterna MH, Turek FW, Keshavarzian A (2014) Circadian disorganization alters intestinal microbiota. PLoS ONE 9(5):e97500. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097500

Thompson RS, Vargas F, Dorrestein PC, Chichlowski M, Berg BM, Fleshner M (2020) Dietary prebiotics alter novel microbial dependent fecal metabolites that improve sleep. Sci Rep 10(1):3848. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60679-y

Li H, Qi T, Huang ZS, Ying Y, Zhang Y, Wang B, Ye L, Zhang B, Chen DL, Chen J (2017) Relationship between gut microbiota and type 2 diabetic erectile dysfunction in Sprague-Dawley rats. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci 37(4):523–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-017-1767-z

Cheung SG, Goldenthal AR, Uhlemann AC, Mann JJ, Miller JM, Sublette ME (2019) Systematic review of gut microbiota and major depression. Front Psychiatry 10:34. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00034

Zheng P, Zeng B, Zhou C, Liu M, Fang Z, Xu X, Zeng L, Chen J, Fan S, Du X, Zhang X, Yang D, Yang Y, Meng H, Li W, Melgiri ND, Licinio J, Wei H, Xie P (2016) Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host's metabolism. Mol Psychiatry 21(6):786–796. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.44

Huang TT, Lai JB, Du YL, Xu Y, Ruan LM, Hu SH (2019) Current Understanding of gut microbiota in mood disorders: an update of human studies. Front Genet 10:98. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00098

Ferreira-Halder CV, Faria AVS, Andrade SS (2017) Action and function of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in health and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 31(6):643–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2017.09.011

Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL (2020) The role of short-chain fatty acids from gut microbiota in gut-brain communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 11:25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00025

Szentirmai E, Millican NS, Massie AR, Kapas L (2019) Butyrate, a metabolite of intestinal bacteria, enhances sleep. Sci Rep 9(1):7035. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43502-1

Cussotto S, Sandhu KV, Dinan TG, Cryan JF (2018) The neuroendocrinology of the microbiota-gut-brain axis: a behavioural perspective. Front Neuroendocrinol 51:80–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.04.002

Tetel MJ, de Vries GJ, Melcangi RC, Panzica G, O'Mahony SM (2018) Steroids, stress and the gut microbiome-brain axis. J Neuroendocrinol 30(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.12548

Org E, Mehrabian M, Parks BW, Shipkova P, Liu X, Drake TA, Lusis AJ (2016) Sex differences and hormonal effects on gut microbiota composition in mice. Gut Microbes 7(4):313–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1203502

Jasarevic E, Morrison KE, Bale TL (2016) Sex differences in the gut microbiome-brain axis across the lifespan. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371(1688):20150122. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0122

Fields CT, Chassaing B, Paul MJ, Gewirtz AT, de Vries GJ (2017) Vasopressin deletion is associated with sex-specific shifts in the gut microbiome. Gut Microbes 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2017.1356557

Yurkovetskiy L, Burrows M, Khan AA, Graham L, Volchkov P, Becker L, Antonopoulos D, Umesaki Y, Chervonsky AV (2013) Gender bias in autoimmunity is influenced by microbiota. Immunity 39(2):400–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.013

Moreno-Indias I, Sanchez-Alcoholado L, Sanchez-Garrido MA, Martin-Nunez GM, Perez-Jimenez F, Tena-Sempere M, Tinahones FJ, Queipo-Ortuno MI (2016) Neonatal androgen exposure causes persistent gut microbiota dysbiosis related to metabolic disease in adult female rats. Endocrinology 157(12):4888–4898. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2016-1317

Harada N, Hanaoka R, Hanada K, Izawa T, Inui H, Yamaji R (2016) Hypogonadism alters cecal and fecal microbiota in male mice. Gut Microbes 7(6):533–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1239680

Sfanos KS, Markowski MC, Peiffer LB, Ernst SE, White JR, Pienta KJ, Antonarakis ES, Ross AE (2018) Compositional differences in gastrointestinal microbiota in prostate cancer patients treated with androgen axis-targeted therapies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 21(4):539–548. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-018-0061-x

Ridlon JM, Ikegawa S, Alves JM, Zhou B, Kobayashi A, Iida T, Mitamura K, Tanabe G, Serrano M, De Guzman A, Cooper P, Buck GA, Hylemon PB (2013) Clostridium scindens: a human gut microbe with a high potential to convert glucocorticoids into androgens. J Lipid Res 54(9):2437–2449. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M038869

Collden H, Landin A, Wallenius V, Elebring E, Fandriks L, Nilsson ME, Ryberg H, Poutanen M, Sjogren K, Vandenput L, Ohlsson C (2019) The gut microbiota is a major regulator of androgen metabolism in intestinal contents. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 317(6):E1182–E1192. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00338.2019

Barrett E, Ross RP, O'Toole PW, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C (2012) gamma-Aminobutyric acid production by culturable bacteria from the human intestine. J Appl Microbiol 113(2):411–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05344.x

Neuman H, Debelius JW, Knight R, Koren O (2015) Microbial endocrinology: the interplay between the microbiota and the endocrine system. FEMS Microbiol Rev 39(4):509–521. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuu010

Seifi M, Rodaway S, Rudolph U, Swinny JD (2018) GABAA receptor subtypes regulate stress-induced colon inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology 155(3):852–864 e853. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.033

Seifi M, Swinny JD (2019) Developmental and age-dependent plasticity of GABAA receptors in the mouse colon: implications in colonic motility and inflammation. Auton Neurosci 221:102579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2019.102579

Diviccaro S, Giatti S, Borgo F, Falvo E, Caruso D, Garcia-Segura LM, Melcangi RC (2020) Steroidogenic machinery in the adult rat colon. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 105732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105732

Giatti S, Diviccaro S, Falvo E, Garcia-Segura LM, Melcangi RC (2020) Physiopathological role of the enzymatic complex 5alpha-reductase and 3alpha/beta-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase in the generation of progesterone and testosterone neuroactive metabolites. Front Neuroendocrinol 57:100836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2020.100836

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was supported from MIUR “Progetto Eccellenza”; Post-Finasteride Foundation to RCM.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed by FB, GC, and RCM. FB, SD, SG, and EF contributed to data acquisition and interpretation, and conducted the experiments. ADM was the biostatistician who performed and supervised the statistical analysis and helped FB and EF in the preparation of the figures. The manuscript was written by FB, SG, GC, and RCM. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Milano-Bicocca Monza-Italy, (protocol number 434/2018).

Informed consent

The participating subjects provided their written informed consent before enrollment.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borgo, F., Macandog, A.D., Diviccaro, S. et al. Alterations of gut microbiota composition in post-finasteride patients: a pilot study. J Endocrinol Invest 44, 1263–1273 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-020-01424-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-020-01424-0