Abstract

Purpose

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common endocrine disorders among women of reproductive age. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin-like motifs (ADAMTS) are involved in inflammation and fertility. The aim of this investigation was to evaluate the serum levels of ADAMTS1, ADAMTS5, ADAMTS9, IL-17, IL-23, IL-33 and to find out the relationship between these inflammatory cytokines and ADAMTSs in PCOS patients.

Methods

A case-control study was performed in a training and research hospital. Eighty patients with PCOS and seventy-eight healthy female volunteers were recruited in the present study. Serum ADAMTS and IL levels were determined by a human enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) in all subjects.

Results

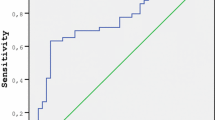

The IL-17A, IL-23 and IL-33 levels were significantly higher in the PCOS patients compared to the controls (p < 0.05). We could not find significant difference between the groups in terms of ADAMTS1, ADAMTS5 and ADAMTS9 levels. IL-17A had positive correlations with LDL cholesterol and IL-33 and negative correlations with ADAMTS1, ADAMTS5, and ADAMTS9. IL-33 had positive correlation with LDL cholesterol and IL-17A. In ROC curve analysis, PCOS can be predicted by the use of IL-17A, IL-23 and IL-33 which at a cut-off value of 8.37 pg/mL (44 % sensitivity, 83 % specificity), 26.75 pg/mL (36 % sensitivity, 64 % specificity) and 14.28 pg/mL (83 % sensitivity, 39 % specificity), respectively.

Conclusions

The results of the study might suggest that ADAMTS and IL molecules have a role in the pathogenesis of the PCOS. Further efforts are needed to establish causality for ADAMTS-IL axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Norman RJ, Dewailly D, Legro RS et al (2007) Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet 370:685–697

Amato MC, Vesco R, Vigneri E et al (2015) Hyperinsulinism and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): role of insulin clearance. J Endocrinol Invest 38(12):1319–1326

Ademoglu EN, Gorar S, Carlıoglu A et al (2014) Plasma nesfatin-1 levels are increased in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 37(8):715–719

Ehrmann DA, Barnes RB, Rosenfield RL et al (1999) Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Care 22:141–146

Coviello AD, Legro RS, Dunaif A (2006) Adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome have an increased risk of the metabolic syndrome associated with increasing and rogen levels independent of obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:492–497

Hardiman P, Pillay OS, Atiomo W (2003) Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometrial carcinoma. Lancet 361:1810–1812

Legro RS (2003) Polycystic ovary syndrome and cardiovascular disease: a premature association. Endocr Rev 2003(24):302–312

Krentz AJ, von Muhlen D, Barrett-Connor E (2007) Searching for poly-cystic ovary syndrome in postmenopausal women: evidence of a dose-effect association with prevalent cardiovascular disease. Menopause 14:284–292

Boulman N, Levy Y, Leiba R et al (2004) Increased C-reactive protein levels in the polycystic ovary syndrome: a marker of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2160–2165

Gonzalez F, Thusu K, Abdel-Rahman E et al (1999) Elevated serum levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha in normal-weight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Metabolism 48:437–441

Escobar-Morreale HF, Botella-Carretero JI, Villuendas G et al (2004) Serum interleukin-18 concentrations are increased in the polycystic ovary syndrome: relationship to insulin resistance and to obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:806–811

Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Spina G, Kouli C et al (2001) Increased endothelin-1 levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and the beneficial effect of metformin therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:4666–4673

Yilmaz H, Celik HT, Ozdemir O et al (2014) Serum galectin-3 levels in women with PCOS. J Endocrinol Invest 37(2):181–187

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group (2004) Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 19:41–47

Kuno K, Kanada N, Nakashima E et al (1997) Molecular cloning of a gene encoding a new type of metalloproteinase-disintegrin family protein with thrombospondin motifs as an inflammation associated gene. J Biol Chem 272:556–562

Apte SS (2009) A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin-type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif (ADAMTS) superfamily: functions and mechanisms. J Biol Chem 284:31493–31497

Shindo T, Kurihara H, Kuno K et al (2000) ADAMTS-1: a metalloproteinase-disintegrin essential for normal growth, fertility, and organ morphology and function. J Clin Invest 105:1345–1352

Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R et al (2008) Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 40:638–645

Rosewell KL, Al-Alem L, Zakerkish F et al (2015) Induction of proteinases in the human preovulatory follicle of the menstrual cycle by human chorionic gonadotropin. Fertil Steril 103(3):826–833

Kilic T, Ural E, Oner G, Sahin T et al (2009) Which cut-off value of high sensitivity C-reactive protein is more valuable for determining long- term prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome? Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 9:280–289

Gokcel A, Ozsahin AK, Sezgin N et al (2003) High prevalence of diabetes in Adana, a southern province of Turkey. Diabetes Care 26:3031–3034

Matzuk MM, Burns KH, Viveiros MM, Eppig JJ (2002) Intracellular communication in the mammalian ovary: oocytes carry the conversation. Science 296:2178–2180

Dong J, Albertini DF, Nishimori N et al (1996) Growth differentiation factor-9 is required during early ovarian folliculogenesis. Nature 383:531–535

Dierich A, Sairam MR, Monaco L et al (1998) Impairing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) signaling in vivo: targeted disruption of the FSH receptor leads to aberrant gametogenesis and hormonal imbalance. PNAS 95:13612–13617

Richards JS (2005) Ovulation: new factors that prepare the oocyte for fertilization. Mol Cell Endocrinol 234:75–79

Brown HM, Dunning KR, Robker RL et al (2006) Requirement for ADAMTS-1′in extracellular matrix remodeling during ovarian folliculogenesis and lympangiogenesis. Dev Biol 300:699–709

Russell DL, Doyle KMH, Ochsner SA et al (2003) Processing and localization of ADAMTS-1 and proteolytic cleavage of versican during cumulus matrix expan-sion and ovulation. J Biol Chem 278:42330–42339

Demircan K, Cömertoğlu İ, Akyol S et al (2014) A new biological marker candidate in female reproductive system diseases: matrix metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS). J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 15:250–255

Shozu M, Minami N, Yokoyama H et al (2005) ADAMTS-1 is involved in normal follicular development, ovulatory process and organization of the medullary vascular network in the ovary. J Mol Endocrinol 35:343–355

Xiao S, Li Y, Li T et al (2014) Evidence for decreased expression of ADAMTS-1 associated with impaired oocyte quality in PCOS patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:1015–1021

Richards JS, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I et al (2005) Regulated expression of ADAMTS family members in follicles and cumulus oocyte complexes: evidence for specific and redundant patterns during ovulation. Biol Reprod 72:1241–1255

Peluffo MC, Murphy MJ, Baughman ST et al (2011) Systematic analysis of protease gene expression in the rhesus macaque ovulatory follicle: metalloproteinase involvement in follicle rupture. Endocrinology 152:3963–7394

Boesgaard TW, Gjesing AP, Grarup N et al (2009) EUGENE2 Consortium. Variant near ADAMTS9 known to associate with type 2 diabetes is related to insulin resistance in offspring of type 2 diabetes patients–EUGENE2 study. PLoS One 4:7236

Glintborg D, Mumm H, Altinok ML et al (2014) Adiponectin, interleukin-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and regional fat mass during 12-month randomized treatment with metformin and/or oral contraceptives in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 37(8):757–764

Orio F Jr, Palomba S, Cascella T et al (2005) The increase of leukocytes as a new putative marker of low-grade chronic inflammation and early cardiovascular risk in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:2–5

Alexander RW (1994) Inflammation and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 331:468–469

Pai JK, Pischon T, Ma J et al (2004) Inflammatory markers and the risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. N Engl J Med 351:2599–2610

Sherlock JP, Taylor PC, Buckley CD (2015) The biology of IL-23 and IL-17 and their therapeutic targeting in rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol 27:71–75

Duvallet E, Semerano L, Assier E et al (2011) Interleukin-23: a key cytokine in inflammatory diseases. Ann Med 43:503–511

Özçaka Ö, Buduneli N, Ceyhan BO et al (2013) Is interleukin-17 involved in the interaction between polycystic ovary syndrome and gingival inflammation? J Periodontol 84:1827–1837

Knebel B, Janssen OE, Hahn S et al (2008) Increased low grade inflammatory serum markers in patients with Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and their relationship to PPARgamma gene variants. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 116:481–486

Cătană CS, Cristea V, Miron N (2011) Is interleukin-17 a proatherogenic biomarker? Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol 70:124–128

Khojasteh-Fard M, Abolhalaj M, Amiri P et al (2012) IL-23 gene expression in PBMCs of patients with coronary artery disease. Dis Markers 33:289–293

Demyanets S, Tentzeris I, Jarai R et al (2014) An increase of interleukin-33 serum levels after coronary stent implantation is associated with coronary in-stent restenosis. Cytokine 67:65–70

Acknowledgments

We thank to TUBITAK for fostering young scientists.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethical Commission of Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK, Grant Number:114S039).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karakose, M., Demircan, K., Tutal, E. et al. Clinical significance of ADAMTS1, ADAMTS5, ADAMTS9 aggrecanases and IL-17A, IL-23, IL-33 cytokines in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 39, 1269–1275 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-016-0472-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-016-0472-2