Abstract

Purpose of Review

Endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) exposure during pregnancy is linked to adverse maternal and child health outcomes that are racially/ethnically disparate. Personal care products (PCP) are one source of EDCs where differences in racial/ethnic patterns of use exist. We assessed the literature for racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy and prenatal PCP chemical exposures.

Recent Findings

Only 3 studies explicitly examined racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy and prenatal exposure to PCP-associated EDCs. Fifty-three articles from 12 cohorts presented EDC concentrations stratified by race/ethnicity or among homogenous US minority populations. Studies reported on phthalates and phenols. Higher phthalate metabolites and paraben concentrations were observed for pregnant non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women. Higher concentrations of benzophenone-3 were observed in non-Hispanic White women; results were inconsistent for triclosan.

Summary

This review highlights need for future research examining pregnancy and prenatal PCP-associated EDCs disparities to understand and reduce racial/ethnic disparities in maternal and child health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Racial/ethnic disparities in early-life health outcomes have been well-documented, with notable disparities including preterm birth [1,2,3], low birth weight [1,2,3], early onset of puberty [4, 5], and childhood asthma [6, 7]. Many of these conditions affect non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations to a greater extent compared to non-Hispanic Whites [1, 8, 9]. While a variety of social and lifestyle factors are at play, recent work suggests that endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) during pregnancy and the prenatal period may also play a role in these disparities [10]. Specifically, non-Hispanic Black women have higher concentrations of many EDCs that are linked to these adverse health outcomes [11,12,13,14,15].

While there are numerous sources of EDCs, including food, clothing, and other consumer products, many of the classes of EDCs that are racially/ethnically disparate are found in personal care products (PCPs), where culturally driven patterns of product use exist [16]. Personal care product use during pregnancy is an important and understudied source of prenatal exposure to EDCs, with implications for later-life maternal and child health [17, 18]. Although research documents exposure to EDC-associated personal care products during pregnancy and the prenatal period [16, 19, 20], as well as associations of EDC concentrations with adverse maternal and child health outcomes, few studies have examined the racial/ethnic patterns of use that may contribute to these higher EDC exposures and their associations with disparate maternal and child health outcomes [10]. Of interest, PCPs may be a possible modifiable factor that could provide opportunities for intervention to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in EDC exposure.

Pregnancy and Prenatal EDC Exposures as Contributors to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Maternal and Child Health Outcomes

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease theory hypothesizes that early life environmental exposures, particularly those occurring during the prenatal period, can have lasting effects on later life health. Thus, when considering EDC exposure, the prenatal period can be a critical window of exposure [21, 22]. Indeed, studies show that higher exposure to EDCs during the prenatal period, including those commonly found in personal care products, has been linked to a number of adverse child health outcomes including low birth weight [23] and preterm birth [13]. For example, data from the racially/ethnically diverse LIFE Study showed that moderately high concentrations of the metabolite monoethyl phthalate (MEP) were associated with over a 200-g decrease in birth weight (β = −200.2; 95% CI: −386.9, −13.4) [23]. Interestingly, non-Hispanic Black women, as well as women from certain Asian subgroups, are 2-times more likely to have a low birth weight infant, suggesting the need to determine whether differences in phthalate exposure could contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in birth weight [1,2,3].

Studies also show associations with decreased gestational age and higher exposure to certain phthalates. For example, in a study of the Puerto Rico Testsite for Exploring Contamination Threats (PROTECT) cohort evaluating 1090 Puerto Rican women, each interquartile range increase in average pregnancy monobutyl phthalate (MBP) concentrations was associated with a 42% increased odds of preterm birth (odds ratio=1.42 95%CI 1.07, 1.88) [24]. With non-Hispanic Black women having a 50% higher risk of preterm birth, this association may suggest the need to evaluate whether EDCs contribute to the striking disparity that leads to adverse infant and child health outcomes. Other adverse health outcomes linked to higher exposure to EDCs exists, such as neurobehavioral, asthma, and allergic disease outcomes [20, 25, 26], conditions that are more prevalent in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic populations. While these disparities are known, and studies show associations between EDCs and these health outcomes, few studies have evaluated whether EDCs could be a modifiable risk factor for these racially/ethnically disparate maternal and child health outcomes.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in EDCs Commonly Found in Personal Care Products

Identifying sources of EDC exposure known to be racially/ethnically disparate may provide critical information for risk reduction in vulnerable populations. Personal care products are an important source of many EDCs that are racially/ethnically disparate; these products have been hypothesized to be key for environmental health disparities [16, 27,28,29]. That said, only a handful of studies have evaluated EDCs commonly used in PCPs as it relates to race/ethnicity. These studies found differences in the pattern of use for hair and skin care products, cosmetics, nail polish, perfumes, and vaginal douches in non-pregnant populations [19, 30,31,32,33,34].

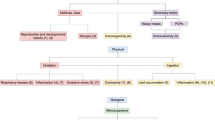

Figure 1 conceptualizes the potential impact of heterogeneous levels of cumulative exposure across racial/ethnic groups throughout early life, showing the possible adverse health implications of the growing disparity. There is a need to investigate chemical concentrations and their sources within the same framework in health disparity research to identify the potential contribution of modifiable risk factors in persistent health disparities. As such, we conducted a scoping review to understand the current state of the literature on racial/ethnic differences in chemical exposures occurring during pregnancy and the prenatal period that are linked to potentially modifiable risk factors. For this, we summarized the literature that examines pregnancy and prenatal exposure to 8 chemicals or classes of chemicals previously identified as chemicals of concern found in PCPs (phthalates, parabens, benzophenone-3, triclosan, cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes, formaldehyde-releasing preservatives, 1,4-dioxane, and diethanolamine) [35,36,37] among women of different racial/ethnic backgrounds in the contiguous US and Puerto Rico. We also reviewed articles that report stratified data on pregnancy and prenatal exposure to the 8 chemicals or classes of concern, but do not examine the racial/ethnic disparities in exposure. Finally, we provide recommendations for research needed to fill the gap in the literature on EDC-associated personal care product use as an important contributor to racial/ethnic maternal and child environmental health disparities.

Examples of high and low cumulative EDC exposure and racial/ethnic disparities at each relevant pregnancy/prenatal period and childhood, showing the possible adverse health implications of the growing exposure disparity. *GDM: gestational diabetes; HDOP: hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Methods

Based on previous literature [35,36,37], we identified a total of 8 EDCs or chemicals of health concern found in personal care products. These included phthalates, benzophenone-3, parabens, triclosan, cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes, formaldehyde-releasing preservatives (formaldehyde, quaternium-15, DMDM hydantoin, imidazolidinyl urea, diazolidinyl urea, polyoxymethylene urea, sodium hydroxymethylglycinate, 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol (bromopol) and glyoxal), 1,4-dioxane, and diethanolamine. We excluded compounds such as asbestos and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are not predominately identified as personal care product chemicals.

To conduct this scoping review on racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy and prenatal exposure, studies were identified by searching PubMed/Medline (National Library of Medicine), EMBASE (Elsevier), Web of Science Core Collection, including the Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index- Science (Thomson Reuters), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL - cochranelibrary.com) from database inception through March 2020. Controlled vocabulary terms (i.e., MeSH, EMTREE) were included when available and appropriate. The search strategies were designed and executed by a librarian with expertise in scoping and systematic reviews (CM). Articles were included if the populations of interest were US-based and reported concentrations during pregnancy and the prenatal period of any of the 8 chemicals or classes of chemicals of interest by maternal race/ethnicity. No language limits or year restrictions were applied. See Supplemental Material 1 for details of the terms used for the search.

Results

The search yielded 2491 references, resulting in 1539 unique records for screening. With the knowledge that there would be only a few studies that align with our aim of examining racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy and prenatal exposure, we also included studies that reported urinary concentrations by racial/ethnic group. Specifically, we included studies that examined personal care product chemical concentrations during pregnancy and the prenatal period in racially/ethnically diverse cohorts or in racially/ethnically homogenous US minority populations (as a proxy for stratified data). We identified 3 studies that explicitly examined the racial/ethnic disparities in exposure to EDCs commonly used in personal care products during pregnancy and the prenatal period (tier 1) and 53 articles that presented racially/ethnically stratified exposure data in the contiguous US and Puerto Rico. For these 53 articles, given that identifying and evaluating differences in exposure by race/ethnicity was not the primary aim of the study, we classified these studies as tier 2.

Of the 56 articles identified as containing data on racial/ethnic differences in personal care product-associated EDC concentrations, all papers covered one or two chemical classes: phthalates (43 articles) or phenols (17 articles). Six papers reported on both chemical classes. Among the articles on phenols, most focused on triclosan and a few on benzophenone-3. No studies evaluating racial/ethnic differences in other chemicals, such as cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes and formaldehyde-releasing preservatives were found. Also, the vast majority of studies evaluated racially homogenous cohorts, specifically non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic populations.

Phthalates

Phthalic acid esters are a class of industrial and multi-use chemicals that can be found in a variety of consumer products [37]. Phthalates are ubiquitous in our environment and can be detected in food, consumer, and personal care products, indoor air, indoor dust, and inside vehicles [38]. Due to their short half-life (from 5 h to less than 24 h), concentrations are representative of recent exposure compared to chronic or cumulative exposure [37, 39]. Unlike the parent compounds, it is thought that phthalate metabolites are bioactive, with the ability to bind to nuclear receptors, altering normal hormone functioning and the regulation of hormonal pathways [40,41,42]. With that, phthalate metabolites are typically measured to assess concentrations and potential exposures in populations.

Given their presence in personal care products, we focused on studies reporting information on low molecular weight phthalates, such as diethyl phthalate (DEP), di-iso-butyl phthalate (DiBP), and di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) used in solvents, medications, and personal care products [38, 43]. Among those studies that assessed phthalates used in personal care products during pregnancy and the prenatal period, three US studies met the tier 1 criteria (Table 1) [44••, 45••, 46••]. Two studies that examined a population recruited from the Medical University of South Carolina found that non-Hispanic Black women had significantly higher urinary concentrations of MBP, mono-isobutyl phthalate (MiBP), monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP), and MEP compared to non-Hispanic White women (p<0.005) [44••, 45••]. Similarly, James-Todd et al. evaluated urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations in a diverse cohort and found higher concentrations of MBP, MiBP, MBzP, and MEP among non-Hispanic Black women, Hispanic women, and women who selected “Other” race/ethnicity compared to non-Hispanic White women. Specifically, non-Hispanic Black women had a baseline specific gravity adjusted geometric mean (GM) MEP of 286.0μg/L compared to 98.7μg/L for non-Hispanic White women. Interestingly, MEP decreased throughout pregnancy for Hispanic women and increased in late pregnancy for non-Hispanic Black women [46••]. Changes in metabolites may be attributed to different product use or changing perceptions of risk during pregnancy [47]. Importantly, these findings reflect higher exposure to personal care product phthalates, such as DBP and DEP during pregnancy, which may illustrate differences in modifiable product use by race/ethnicity.

Evidence that product use may drive differences in low molecular weight phthalate exposure comes from a small set of studies. In a study of 186 pregnant non-Hispanic Black and Dominican women, perfume users had 2.3 times higher urinary MEP concentrations compared to non-perfume users [48]. These estimates were based on multivariable logistic regression parameters that were exponentiated to report the multiplicative fold change between users and non-users of perfume in the last 48 h. Another study in New York City found that non-Hispanic Black women were more likely to use all types of hair products, specifically products containing placenta or EDCs on the product labels—such as fragrance and parabens—compared to non-Hispanic White women [16].

Forty papers from nine cohorts met the tier 2 criteria of presenting racial/ethnic stratified phthalate exposure data, without an explicit focus on disparities (Table 2) [24, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. From those, 31 papers in three racially/ethnically homogenous US minority cohorts (Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas-CHAMACOS, Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health-CCCEH, and PROTECT) presented urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites among pregnant Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women. As some cohorts published multiple studies stratified by race/ethnicity, we present the most complete data in Table 2 from cohorts with multiple studies, in addition to those cohorts publishing single papers.

When evaluating studies from relatively homogenous cohorts, we compared findings to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). For example, in the CHAMACOS study, a longitudinal birth cohort in Salinas Valley, California consisting of Mexican American women, pregnant women generally had phthalate metabolite concentrations that were consistent with trends in comparable US women from NHANES [50].

The CCCEH cohort comprised of non-Hispanic Black and Dominican pregnant women living in New York City reported higher GM concentrations of MnBP, MiBP, and MEP (approximately 33–34 weeks of gestation) compared to NHANES participants of similar ages [48, 60, 65, 67, 86]. Among Puerto Rican women participating in the PROTECT study aiming to evaluate the potential relationship between environmental chemicals and preterm birth in the Northern Karst Region, urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations that were collected three times during pregnancy (approximately 16–20 weeks, 20–24 weeks, and 24–28 weeks of gestation) had higher reported MEP and MBP concentrations compared to NHANES participants [24]. Additional studies with diverse participants reported similar or lower concentrations of phthalate metabolites compared to NHANES participants [51,52,53,54,55,56, 58, 79, 85].

Given that exposure during pregnancy and the prenatal period to phthalate metabolites has been associated with adverse maternal and child outcomes [13, 14, 57, 87, 88], it is imperative to consider the health effects of these higher exposures in racial/ethnic minorities. Future research is needed to understand whether these observed differences in exposure to phthalates associated with personal care products could contribute to some of the disparities seen in the phthalate-associated adverse health outcomes.

Phenols

Triclosan

Triclosan (TCS) is an antibacterial agent that has been found in an array of personal care products, including hand soaps, hand sanitizers, toothpaste, and shampoos [89, 90]. With a short half-life of 21 h, exposure represents recent product use [91]. Differences in triclosan concentrations between countries and within the US have been attributed mainly to differential exposure sources and product use behaviors [92]. Triclosan has been shown to disrupt thyroid hormone homeostasis through activating the human pregnane X receptor (PXR) and the inhibition of diiodothyronine sulfotransferases [93, 94]. Animal studies have also demonstrated that triclosan may inhibit the circulation of hormones, resulting in altered gene expression in the placenta and impaired fetal development [95].

Fifteen tier 2 papers from eight different cohorts reported the concentrations of triclosan by race/ethnicity among pregnant women (Table 3) [28, 53, 57, 72, 96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106]. One study of Puerto Rican pregnant women reported higher concentrations of triclosan compared to a representative subset of women participating in NHANES [99]. Comparatively, several studies with predominantly non-Hispanic White participants from the Healthy Start study and the National Children’s Study (NCS) were found to have lower [53, 98] or similar triclosan concentrations compared to 2005–2010 NHANES [96, 97, 103].

When evaluating triclosan concentrations within a study by race/ethnicity, results were inconsistent. For example, data from the Healthy Start and the Health Outcomes and Measures of the Environment (HOME) study reported higher concentrations of triclosan among pregnant non-Hispanic White women compared to other racial/ethnic groups (participants were primarily non-Hispanic White) [53, 96]. On the other hand, two studies found that women with the race classified as “Other” had higher reported concentrations of triclosan [97, 100]. Larger multi-racial/ethnic studies are needed to further evaluate whether triclosan contributes to environmental health disparities, given these inconsistent findings.

Parabens

Parabens are another ubiquitous class of synthetic chemicals [107]. These chemicals are used as antimicrobial agents and preservatives for personal care products, pharmaceuticals, and food products to increase their shelf life. Methyl paraben, propyl paraben, and butyl paraben are the most commonly used parabens in personal care products [18, 108, 109]. This class of chemicals also has a short half-life (for example, butyl paraben was found to be excreted in 2.6±0.1 mg/24 h) [110], and biomarkers reflect more recent exposures [111]. Parabens are found to be weak estrogens that can bind to estrogen receptors α and β [112, 113]. Although less studied than phthalates or triclosan, US studies using NHANES have reported that Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women across the US have higher concentrations of parabens compared to non-Hispanic White women [11, 114].

Thirteen tier 2 studies among 7 different cohorts reported racial/ethnic stratified concentrations of parabens among pregnant women (Table 3) [28, 52, 53, 57, 71, 97,98,99,100, 104,105,106, 115]. Compared to NHANES, one study of 1003 Puerto Rican women that collected urine at 16–20 and 24–28 weeks gestation found 2-fold higher median concentrations of butyl paraben [99]. Interestingly, like the PROTECT study, CHAMACOS also reported high concentrations of parabens compared to NHANES participants [71]. In a multi-ethnic study that explicitly reported concentrations of parabens for non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic/Caribbean immigrants in the US, relative to a representative sample of women participating in NHANES the median concentrations of methyl paraben and propyl paraben were 4.4-fold and 8.7-fold higher, respectively [115]. These findings suggest further investigation as to whether higher paraben concentrations could contribute to related health disparities.

Benzophenone-3

Benzophenone-3 (BP3) is a UV-filter found in sunscreens and other personal care products [105, 116]. BP3 is ubiquitous among individuals living in the US indicating widespread exposure [117]. Benzophenones are found to cause androgenic effects and disrupt nuclear and estrogen receptors [118]. Specifically, BP3 is found to activate estrogen receptors α and β in animal studies [119]. Temporal trends from the US NHANES population indicate that non-Hispanic Blacks have lower and stable mean concentrations of BP3, while non-Hispanic Whites have higher concentrations [120]. This finding may be explained by the evidence that non-Hispanic Blacks are seven times less likely to use sunscreen compared to non-Hispanic Whites who report severe sunburns [121].

Nine studies in five different cohorts met the tier 2 criteria and reported racial/ethnic stratified concentrations of BP3 metabolites among pregnant women (Table 3) [28, 49, 65, 75, 99,100,101,102,103]. Data from the PROTECT study reported higher concentrations of BP3 compared to women of reproductive age from NHANES [99]. Another study using the Healthy Start cohort—with a diverse, but predominantly non-Hispanic White study population—reported higher BP3 concentrations compared to a sample of pregnant NHANES participants [53]. On the other hand, the CHAMACOS cohort participants had similar BP3 concentrations to women participating in NHANES [71]. Within the LIFECODES pregnancy cohort, non-Hispanic White women had higher concentrations of BP3 compared to non-Hispanic Black women and women identified as “Other” [97]. Future studies should assess the impact of these differences on associated health outcomes to determine whether this exposure contributes to protective or adverse health effects.

Cyclic Volatile Methylsiloxanes, Formaldehyde-Releasing Preservatives, 1,4-Dioxane, and Diethanolamine

To our knowledge, no US-based studies have examined the racial/ethnic differences in pregnancy and prenatal exposure to cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes, formaldehyde-releasing preservatives, 1,4-dioxane, or diethanolamine. There is limited epidemiologic research, in general, examining exposure to the aforementioned chemicals as they relate to exposure differences by race/ethnicity, as well as health outcomes, leaving a gap in the knowledge regarding personal care product chemicals of concern.

While epidemiological studies are limited for these chemicals, research has begun to explore the potential mechanisms of action, particularly for cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes and diethanolamine as potential EDCs. Specifically, research has examined chemicals in products used and marketed to non-Hispanic Black women. For example, Helm et al. tested 18 products used by non-Hispanic Black women and found that a hair relaxer and multiple anti-frizz products had concentrations of octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane (D4), decamethylcyclopentaasiloxane (D5), and dodecamethylcyclo-hexasiloxane (D6) above 1000 μg/g [36]. Additionally, diethanolamine was found in a leave-in conditioner and multiple hair relaxers at concentrations between 100–1000 μg/g. Expanding research aims to include other emerging EDCs of concern that may have racial/ethnic differences in exposure, particularly given the racial/ethnic differences in product use [16, 19], is needed to help further explain the disparities in maternal and child health outcomes.

Call to Action for Further Research

In this review, we presented evidence on exposure disparities to EDCs associated with personal care products—phthalates and several phenolic compounds (triclosan, parabens, and benzophenone-3)—during pregnancy and the prenatal period. We aimed to provide a summary of the evidence on racial/ethnic differences in exposure to support the argument that disparities in exposure to these EDCs during the pregnancy and prenatal period could contribute to the disparities in maternal and child health outcomes that disproportionately burden certain racial/ethnic groups. Since product use is modifiable, fully examining pregnancy and prenatal exposures to EDCs commonly used in personal care products could provide an important opportunity for future intervention and public health recommendations.

While 43 studies reported phthalate metabolite concentrations by race/ethnicity, few studies reported stratified concentrations of other personal care product chemicals and even less aimed to examine disparities in exposure, particularly as it related to health outcomes. In total, only three articles’ primary objective was to examine the racial/ethnic disparities in exposure during pregnancy and the prenatal period. Instead, the majority of studies simply presented stratified exposure data by race/ethnicity as a descriptor of their exposure of interest. Several potentially important chemicals remained missing, and importantly, little information was available on Asian or ‘Other’ racial/ethnic groups. An important example is that emerging evidence suggests that triclocarban may be an important chemical to evaluate [99, 101, 104,105,106]. While not originally covered in this review, Puerto Rican women were found to have 37-times higher levels of triclocarbon than women of reproductive age participating in NHANES [104]. Reasons for these differences are unclear and few studies have evaluated sources of exposure differences, including sociocultural drivers of usage patterns that could contribute to these disparities.

As a result, we suggest utilizing both the information gained from studies describing racial/ethnic differences and those describing associations between EDCs and adverse health outcomes to fill the gaps in the research examining environmental racial/ethnic disparities, particularly as it relates to pregnancy and prenatal exposure to EDC-associated personal care products. To leverage this information and reduce health disparities in this area, we suggest:

-

Increased research examining endocrine disrupting chemicals as a potential risk factor for racial/ethnic disparities in maternal and child health outcomes among large, diverse populations either as single studies or in pooled studies.

-

Examination of personal care product chemical exposure in racially/ethnically diverse populations/cohorts, including detailed reporting of race/ethnicity to examine potential disparities in exposure among women and children in other racial/ethnic groups, including Asian, and mixed or multiracial participants.

-

Assessment of personal care products and other sources of EDCs in the same studies to understand associations and develop interventions for these potentially modifiable risk factors of racial/ethnic disparities in EDC exposures and related health disparities [122].

-

Joint examination of sociocultural and socioeconomic determinants of disparities in exposure and race/ethnicity, as they relate to EDC and health associations

-

Inclusion of results stratified by race/ethnicity when reporting endocrine disrupting chemical concentrations

-

Examination of pregnancy and prenatal exposure to personal care product chemicals that have not been studied, but may be particularly important to vulnerable populations based on patterns of personal care product use [36] (ex: cyclic volatile methylsiloxanes, formaldehyde releasing preservatives, 1,4-dioxane, diethanolamine)

Conclusion

Based on the current literature, the overall pattern of exposure to environmental EDCs commonly found in personal care products differs by race/ethnicity during pregnancy and the prenatal period. As this is a critical time period of development for a variety of health outcomes ranging from pregnancy complications to asthma and neurobehavioral outcomes in children, understanding all contributors to disparities linked to these conditions is imperative. While the vast majority of studies simply adjusted for race/ethnicity, a number of studies—mainly those focused on phthalates and phenols—provided data on chemical concentrations stratified by race/ethnicity or within racial/ethnic US minority-only populations, revealing that non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics were high-exposure groups for many of these EDCs. Given that these same groups are also at higher risk of many of the associated health outcomes linked to these EDCs, it is critical to better understand whether patterns of personal care product use can explain these disparities. This review calls for future work to better elucidate the contribution that personal care product EDCs may have to existing racial/ethnic disparities in both exposure and health outcomes. Studies are needed to understand the sociocultural drivers of these exposure disparities, and future work must consider possible interventions to reduce exposure and persistent racial/ethnic health disparities related to these chemical exposures.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Manuck TA. Racial and ethnic differences in preterm birth: A complex, multifactorial problem. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(8):511–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2017.08.010.

Kistka ZAF, Palomar L, Lee KA, et al. Racial disparity in the frequency of recurrence of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(2):131.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.093.

Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: Final Data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(12):1–64.

Ramnitz MS, Lodish MB. Racial disparities in pubertal development. Semin Reprod Med. 2013;31(5):333–9. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1348891.

Butts SF, Seifer DB. Racial and ethnic differences in reproductive potential across the life cycle. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(3):681–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.047.

Bhan N, Kawachi I, Glymour MM, Subramanian SV. Time Trends in Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Asthma Prevalence in the United States From the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Study (1999-2011). Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1269–75. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302172.

Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Simon AE, et al. Trends in racial disparities for asthma outcomes among children 0 to 17 years, 2001-2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(3):547–53.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.037.

National Center for Health S. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Prevalence of Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Learning Disabilities Among US Children Aged 3-17 Years, 2020.

Salsberry PJ, Reagan PB, Pajer K. Growth Differences by Age of Menarche in African American and White Girls. Nurs Res. 2009;58(6):382–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181b4b921.

James-Todd TM, Chiu Y-H, Zota AR. Racial/ethnic disparities in environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals and women's reproductive health outcomes: epidemiological examples across the life course. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2016;3(2):161–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-016-0073-9.

Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong L-Y, Bishop AM, Needham LL. Urinary Concentrations of Four Parabens in the U.S. Population: NHANES 2005–2006. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(5):679–85. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0901560.

Silva MJ, Barr DB, Reidy JA, Malek NA, Hodge CC, Caudill SP, et al. Urinary levels of seven phthalate metabolites in the U.S. population from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2000. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(3):331–8.

Ferguson KK, McElrath TF, Meeker JD. Environmental phthalate exposure and preterm birth. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):61–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3699.

Ferguson KK, McElrath TF, Ko Y-A, et al. Variability in urinary phthalate metabolite levels across pregnancy and sensitive windows of exposure for the risk of preterm birth. Environ Int. 2014;70:118–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2014.05.016.

DeWitt JC, Patisaul HB. Endocrine disruptors and the developing immune system. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2018;10:31–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cotox.2017.12.005.

James-Todd T, Senie R, Terry MB. Racial/ethnic differences in hormonally-active hair product use: a plausible risk factor for health disparities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(3):506–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-011-9482-5.

Bellavia A, Mínguez-Alarcón L, Ford JB, Keller M, Petrozza J, Williams PL, et al. Association of self-reported personal care product use with blood glucose levels measured during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. Sci Total Environ. 2019;695:133855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133855.

Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, et al. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24(5):459–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2013.69 [published Online First: 2013/10/24].

James-Todd T, Terry MB, Rich-Edwards J, Deierlein A, Senie R. Childhood Hair Product Use and Earlier Age at Menarche in a Racially Diverse Study Population: A Pilot Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(6):461–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.01.009.

Just AC, Whyatt RM, Perzanowski MS, Calafat AM, Perera FP, Goldstein IF, et al. Prenatal Exposure to Butylbenzyl Phthalate and Early Eczema in an Urban Cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(10):1475–80. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104544.

Meeker JD. Exposure to Environmental Endocrine Disruptors and Child Development. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(6):E1–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.241.

Braun JM. Early-life exposure to EDCs: role in childhood obesity and neurodevelopment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(3):161–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2016.186.

Smarr MM, Grantz KL, Sundaram R, Maisog JM, Kannan K, Louis GMB. Parental urinary biomarkers of preconception exposure to bisphenol A and phthalates in relation to birth outcomes. Environ Health. 2015;14:73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-015-0060-5.

Ferguson KK, Rosen EM, Rosario Z, Feric Z, Calafat AM, McElrath TF, et al. Environmental phthalate exposure and preterm birth in the PROTECT birth cohort. Environ Int. 2019;132:105099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105099.

Quirós-Alcalá L, Hansel NN, McCormack MC, et al. Paraben exposures and asthma-related outcomes among children from the US general population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(3):948–56.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.021.

Kobrosly RW, Evans S, Miodovnik A, Barrett ES, Thurston SW, Calafat AM, et al. Prenatal phthalate exposures and neurobehavioral development scores in boys and girls at 6-10 years of age. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(5):521–8. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307063.

Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014;93(6):289–93.

Meeker JD, Cantonwine DE, Rivera-González LO, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, Calafat AM, et al. Distribution, variability, and predictors of urinary concentrations of phenols and parabens among pregnant women in Puerto Rico. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(7):3439–47. https://doi.org/10.1021/es400510g.

Ranjit N, Siefert K, Padmanabhan V. Bisphenol-A and disparities in birth outcomes: a review and directions for future research. J Perinatol. 2010;30(1):2–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2009.90.

Gaston SA, James-Todd T, Harmon Q, Taylor KW, Baird D, Jackson CL. Chemical/straightening and other hair product usage during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood among African-American women: potential implications for health. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2020;30(1):86–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-019-0186-6.

Wu XM, Bennett DH, Ritz B, et al. Usage pattern of personal care products in California households. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48(11):3109–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2010.08.004.

Branch F, Woodruff TJ, Mitro SD, Zota AR. Vaginal douching and racial/ethnic disparities in phthalates exposures among reproductive-aged women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2004. Environ Health. 2015;14:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-015-0043-6.

McKee MD, Baquero M, Fletcher J. Vaginal hygiene practices and perceptions among women in the urban Northeast. Women Health. 2009;49(4):321–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630240903158412.

Taylor KW, Troester MA, Herring AH, Engel LS, Nichols HB, Sandler DP, et al. Associations between Personal Care Product Use Patterns and Breast Cancer Risk among White and Black Women in the Sister Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(2):027011. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP1480.

Chow ET, Mahalingaiah S. Cosmetics use and age at menopause: is there a connection? Fertil Steril. 2016;106(4):978–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.08.020.

Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, Rudel RA, Dodson RE. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by Black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.03.030.

Hauser R, Calafat A. Phthalates and Human Health. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(11):806–18. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2004.017590.

Koniecki D, Wang R, Moody RP, Zhu J. Phthalates in cosmetic and personal care products: Concentrations and possible dermal exposure. Environ Res. 2011;111(3):329–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2011.01.013.

Hoppin JA, Brock JW, Davis BJ, Baird DD. Reproducibility of urinary phthalate metabolites in first morning urine samples. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(5):515–8.

Center for Disease C, Prevention. Phthalates Overview, 2019.

Kessler W, Numtip W, Grote K, Csanády GA, Chahoud I, Filser JG. Blood burden of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and its primary metabolite mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in pregnant and nonpregnant rats and marmosets. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;195(2):142–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.014.

Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon J-P, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, et al. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(4):293–342. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2009-0002.

Schettler T. Human exposure to phthalates via consumer products. Int J Androl. 2006;29(1):134–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00567.x.

•• Bloom MS, Wenzel AG, Brock JW, et al. Racial disparity in maternal phthalates exposure; Association with racial disparity in fetal growth and birth outcomes. Environ Int. 2019;127:473–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.04.005. Studies of prenatal/pregnancy EDC exposure that primarily sought to evaluate racial/ethnic differences, these studies are critical to providing insight to the possible racial/ethnic disparities in adverse maternal and child health outcomes.

•• Wenzel AG, Brock JW, Cruze L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of phthalate exposure in pregnant women in Charleston, SC. Chemosphere. 2018;193:394–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.11.019. Studies of prenatal/pregnancy EDC exposure that primarily sought to evaluate racial/ethnic differences, these studies are critical to providing insight to the possible racial/ethnic disparities in adverse maternal and child health outcomes.

•• James-Todd TM, Meeker JD, Huang T, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in phthalate metabolite concentration changes across full-term pregnancies. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2017;27(2):160–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2016.2. Studies of prenatal/pregnancy EDC exposure that primarily sought to evaluate racial/ethnic differences, these studies are critical to providing insight to the possible racial/ethnic disparities in adverse maternal and child health outcomes.

Marie C, Cabut S, Vendittelli F, Sauvant-Rochat MP. Changes in Cosmetics Use during Pregnancy and Risk Perception by Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13040383.

Just AC, Adibi JJ, Rundle AG, Calafat AM, Camann DE, Hauser R, et al. Urinary and air phthalate concentrations and self-reported use of personal care products among minority pregnant women in New York City. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2010;20(7):625–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2010.13.

Morgenstern R, Whyatt RM, Insel BJ, Calafat AM, Liu X, Rauh VA, et al. Phthalates and Thyroid Function in Preschool Age Children: Sex Specific Associations. Environ Int. 2017;106:11–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.05.007.

Hyland C, Mora AM, Kogut K, Calafat AM, Harley K, Deardorff J, et al. Prenatal Exposure to Phthalates and Neurodevelopment in the CHAMACOS Cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127:127(10). https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP5165.

Wenzel AG, Bloom MS, Butts CD, Wineland RJ, Brock JW, Cruze L, et al. Influence of race on prenatal phthalate exposure and anogenital measurements among boys and girls. Environ Int. 2018;110:61–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2017.10.007.

Mínguez-Alarcόn L, Messerlian C, Bellavia A, et al. Urinary concentrations of bisphenol A, parabens and phthalate metabolite mixtures in relation to reproductive success among women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Environ Int. 2019;126:355–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.02.025.

Polinski KJ, Dabelea D, Hamman RF, Adgate JL, Calafat AM, Ye X, et al. Distribution and predictors of urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites and phenols among pregnant women in the Healthy Start Study. Environ Res. 2018;162:308–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.025.

Werner EF, Braun JM, Yolton K, Khoury JC, Lanphear BP. The association between maternal urinary phthalate concentrations and blood pressure in pregnancy: The HOME Study. Environ Health. 2015;14:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-015-0062-3.

Ferguson KK, McElrath TF, Chen Y-H, et al. Urinary Phthalate Metabolites and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Pregnant Women: A Repeated Measures Analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(3):210–6. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307996.

Serrano SE, Karr CJ, Seixas NS, Nguyen R, Barrett E, Janssen S, et al. Dietary Phthalate Exposure in Pregnant Women and the Impact of Consumer Practices. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(6):6193–215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110606193.

Harley KG, Berger KP, Kogut K, Parra K, Lustig RH, Greenspan LC, et al. Association of phthalates, parabens and phenols found in personal care products with pubertal timing in girls and boys. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(1):109–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey337.

James-Todd TM, Meeker JD, Huang T, Hauser R, Ferguson KK, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Pregnancy urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and gestational diabetes risk factors. Environ Int. 2016;96:118–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.09.009.

Harley KG, Berger K, Rauch S, Kogut K, Claus Henn B, Calafat AM, et al. Association of prenatal urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and childhood BMI and obesity. Pediatr Res. 2017;82(3):405–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2017.112.

Whyatt RM, Liu X, Rauh VA, Calafat AM, Just AC, Hoepner L, et al. Maternal Prenatal Urinary Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations and Child Mental, Psychomotor, and Behavioral Development at 3 Years of Age. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(2):290–5. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1103705.

Adibi JJ, Buckley JP, Lee MK, Williams PL, Just AC, Zhao Y, et al. Maternal urinary phthalates and sex-specific placental mRNA levels in an urban birth cohort. Environ Health. 2017;16(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0241-5.

Balalian AA, Whyatt RM, Liu X, Insel BJ, Rauh VA, Herbstman J, et al. Prenatal and Childhood Exposure to Phthalates and Motor Skills at Age 11 Years. Environ Res. 2019;171:416–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.01.046.

Ipapo KN, Factor-Litvak P, Whyatt RM, Calafat AM, Diaz D, Perera F, et al. Maternal Prenatal Urinary Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations and Visual Recognition Memory among Infants at 27 Weeks. Environ Res. 2017;155:7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.01.019.

Maresca MM, Hoepner LA, Hassoun A, Oberfield SE, Mooney SJ, Calafat AM, et al. Prenatal Exposure to Phthalates and Childhood Body Size in an Urban Cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(4):514–20. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408750.

Factor-Litvak P, Insel B, Calafat AM, Liu X, Perera F, Rauh VA, et al. Persistent Associations between Maternal Prenatal Exposure to Phthalates on Child IQ at Age 7 Years. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114003. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114003.

Whyatt RM, Perzanowski MS, Just AC, Rundle AG, Donohue KM, Calafat AM, et al. Asthma in inner-city children at 5-11 years of age and prenatal exposure to phthalates: the Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health Cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(10):1141–6. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1307670.

Adibi JJ, Whyatt RM, Hauser R, Bhat HK, Davis BJ, Calafat AM, et al. Transcriptional Biomarkers of Steroidogenesis and Trophoblast Differentiation in the Placenta in Relation to Prenatal Phthalate Exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(2):291–6. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0900788.

Whyatt RM, Adibi JJ, Calafat AM, Camann DE, Rauh V, Bhat HK, et al. Prenatal di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate exposure and length of gestation among an inner-city cohort. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1213–20. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0325.

Berger K, Eskenazi B, Balmes J, Kogut K, Holland N, Calafat AM, et al. Prenatal high molecular weight phthalates and bisphenol A, and childhood respiratory and allergic outcomes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019;30(1):36–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.12992.

Heggeseth BC, Holland N, Eskenazi B, Kogut K, Harley KG. Heterogeneity in childhood body mass trajectories in relation to prenatal phthalate exposure. Environ Res. 2019;175:22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.04.036.

Berger K, Eskenazi B, Balmes J, Holland N, Calafat AM, Harley KG. Associations between prenatal maternal urinary concentrations of personal care product chemical biomarkers and childhood respiratory and allergic outcomes in the CHAMACOS study. Environ Int. 2018;121(Pt 1):538–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.027.

Berger K, Eskenazi B, Kogut K, Parra K, Lustig RH, Greenspan LC, et al. Association of Prenatal Urinary Concentrations of Phthalates and Bisphenol A and Pubertal Timing in Boys and Girls. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126:126(9). https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP3424.

Tindula G, Murphy SK, Grenier C, Huang Z, Huen K, Escudero-Fung M, et al. DNA methylation of imprinted genes in Mexican–American newborn children with prenatal phthalate exposure. Epigenomics. 2018;10(7):1011–26. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi-2017-0178.

Zhou M, Ford B, Lee D, Tindula G, Huen K, Tran V, et al. Metabolomic Markers of Phthalate Exposure in Plasma and Urine of Pregnant Women. Front Public Health. 2018;6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00298.

Solomon O, Yousefi P, Huen K, Gunier RB, Escudero-Fung M, Barcellos LF, et al. Prenatal phthalate exposure and altered patterns of DNA methylation in cord blood. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2017;58(6):398–410. https://doi.org/10.1002/em.22095.

Tran V, Tindula G, Huen K, Bradman A, Harley K, Kogut K, et al. Prenatal phthalate exposure and 8-isoprostane among Mexican-American children with high prevalence of obesity. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2017;8(2):196–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2040174416000763.

Holland N, Huen K, Tran V, et al. Urinary Phthalate Metabolites and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in a Mexican-American Cohort: Variability in Early and Late Pregnancy. Toxics. 2016;4:4(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics4010007.

Huen K, Calafat AM, Bradman A, Yousefi P, Eskenazi B, Holland N. Maternal phthalate exposure during pregnancy is associated with DNA methylation of LINE-1 and Alu repetitive elements in Mexican-American children. Environ Res. 2016;148:55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.03.025.

Johns LE, Ferguson KK, Cantonwine DE, McElrath TF, Mukherjee B, Meeker JD. Urinary BPA and Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations and Plasma Vitamin D Levels in Pregnant Women: A Repeated Measures Analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(8):087026. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP1178.

Rodríguez-Carmona Y, Ashrap P, Calafat AM, Ye X, Rosario Z, Bedrosian LD, et al. Determinants and characterization of exposure to phthalates, DEHTP and DINCH among pregnant women in the PROTECT birth cohort in Puerto Rico. J Exposure Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2020;30(1):56–69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-019-0168-8.

Cathey AL, Watkins D, Rosario ZY, Vélez C, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, et al. Associations of Phthalates and Phthalate Replacements With CRH and Other Hormones Among Pregnant Women in Puerto Rico. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3(6):1127–49. https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2019-00010.

Johns LE, Ferguson KK, Soldin OP, Cantonwine DE, Rivera-González LO, del Toro LV, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolites in relation to maternal serum thyroid and sex hormone levels during pregnancy: a longitudinal analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-13-4.

Cantonwine DE, Cordero JF, Rivera-González LO, Anzalota del Toro LV, Ferguson KK, Mukherjee B, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations among pregnant women in Northern Puerto Rico: Distribution, temporal variability, and predictors. Environ Int. 2014;62:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2013.09.014.

Ferguson KK, Cantonwine DE, Rivera-González LO, Loch-Caruso R, Mukherjee B, Anzalota del Toro LV, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite associations with biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress across pregnancy in Puerto Rico. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(12):7018–25. https://doi.org/10.1021/es502076j.

Martino-Andrade AJ, Liu F, Sathyanarayana S, Barrett ES, Redmon JB, Nguyen RHN, et al. Timing of prenatal phthalate exposure in relation to genital endpoints in male newborns. Andrology. 2016;4(4):585–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12180.

Adibi JJ, Whyatt RM, Williams PL, Calafat AM, Camann D, Herrick R, et al. Characterization of phthalate exposure among pregnant women assessed by repeat air and urine samples. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(4):467–73. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10749.

Gascon M, Casas M, Morales E, et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A and phthalates and childhood respiratory tract infections and allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(2):370–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.030 [published Online First: 2014/12/03].

Chiu Y-H, Mínguez-Alarcón L, Ford JB, Keller M, Seely EW, Messerlian C, et al. Trimester-specific urinary bisphenol A concentrations and blood glucose levels among pregnant women from a fertility clinic. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(4):1350–7.

Dix-Cooper L, Kosatsky T. Use of antibacterial toothpaste is associated with higher urinary triclosan concentrations in Asian immigrant women living in Vancouver, Canada. Sci Total Environ. 2019;671:897–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.379.

Bedoux G, Roig B, Thomas O, Dupont V, le Bot B. Occurrence and toxicity of antimicrobial triclosan and by-products in the environment. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2012;19(4):1044–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-011-0632-z.

Jackson-Browne MS, Papandonatos GD, Chen A, Yolton K, Lanphear BP, Braun JM. Early-life triclosan exposure and parent-reported behavior problems in 8-year-old children. Environ Int. 2019;128:446–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.01.021.

Wang C-F, Tian Y. Reproductive endocrine-disrupting effects of triclosan: Population exposure, present evidence and potential mechanisms. Environ Pollut. 2015;206:195–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.07.001.

Dann AB, Hontela A. Triclosan: environmental exposure, toxicity and mechanisms of action. J Appl Toxicol. 2011;31(4):285–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.1660.

Paul KB, Hedge JM, DeVito MJ, et al. Short-term Exposure to Triclosan Decreases Thyroxine In Vivo via Upregulation of Hepatic Catabolism in Young Long-Evans Rats. Toxicol Sci. 2010;113(2):367–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfp271.

Feng Y, Zhang P, Zhang Z, Shi J, Jiao Z, Shao B. Endocrine Disrupting Effects of Triclosan on the Placenta in Pregnant Rats. PLoS One. 2016;11(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154758.

Etzel TM, Calafat AM, Ye X, Chen A, Lanphear BP, Savitz DA, et al. Urinary Triclosan Concentrations during Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes. Environ Res. 2017;156:505–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.04.015.

Aung MT, Ferguson KK, Cantonwine DE, McElrath TF, Meeker JD. Preterm birth in relation to the bisphenol A replacement, bisphenol S, and other phenols and parabens. Environ Res. 2019;169:131–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.10.037.

Mortensen ME, Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Wright DJ, Pirkle JL, et al. Urinary Concentrations of Environmental Phenols in Pregnant Women in a Pilot Study of the National Children’s Study. Environ Res. 2014;129:32–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2013.12.004.

Ashrap P, Watkins D, Calafat AM, et al. Elevated Concentrations of Urinary Triclocarban, Phenol and Paraben among Pregnant Women in Northern Puerto Rico: Predictors and Trends. Environ Int. 2018;121(Pt 1):990–1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.020.

Lee-Sarwar K, Hauser R, Calafat AM, et al. Prenatal and early-life triclosan and paraben exposure and allergic outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):269–78.e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.09.029.

Pycke BFG, Geer LA, Dalloul M, Abulafia O, Jenck AM, Halden RU. Human Fetal Exposure to Triclosan and Triclocarban in an Urban Population from Brooklyn, New York. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(15):8831–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/es501100w.

Kalloo G, Calafat AM, Chen A, Yolton K, Lanphear BP, Braun JM. Early life Triclosan exposure and child adiposity at 8 Years of age: a prospective cohort study. Environ Health. 2018;17:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0366-1.

Stacy SL, Eliot M, Etzel T, Papandonatos G, Calafat AM, Chen A, et al. Patterns, Variability, and Predictors of Urinary Triclosan Concentrations during Pregnancy and Childhood. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51(11):6404–13. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b00325.

Aker AM, Ferguson KK, Rosario ZY, Mukherjee B, Alshawabkeh AN, Calafat AM, et al. A repeated measures study of phenol, paraben and Triclocarban urinary biomarkers and circulating maternal hormones during gestation in the Puerto Rico PROTECT cohort. Environ Health. 2019;18(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-019-0459-5.

Aker AM, Ferguson KK, Rosario ZY, Mukherjee B, Alshawabkeh AN, Cordero JF, et al. The associations between prenatal exposure to triclocarban, phenols and parabens with gestational age and birth weight in northern Puerto Rico. Environ Res. 2019;169:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.10.030.

Geer LA, Pycke BFG, Waxenbaum J, Sherer DM, Abulafia O, Halden RU. Association of birth outcomes with fetal exposure to parabens, triclosan and triclocarban in an immigrant population in Brooklyn, New York. J Hazard Mater. 2017;323:177–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.03.028.

Ye X, Bishop AM, Reidy JA, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Parabens as Urinary Biomarkers of Exposure in Humans. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(12):1843–6. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.9413.

Nassan FL, Coull BA, Gaskins AJ, Williams MA, Skakkebaek NE, Ford JB, et al. Personal Care Product Use in Men and Urinary Concentrations of Select Phthalate Metabolites and Parabens: Results from the Environment And Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(8). https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP1374.

Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG, Rudel RA. Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(7):935–43. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104052.

Janjua NR, Frederiksen H, Skakkebæk NE, Wulf HC, Andersson AM. Urinary excretion of phthalates and paraben after repeated whole-body topical application in humans. Int J Androl. 2008;31(2):118–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00841.x.

Smith KW, Braun JM, Williams PL, Ehrlich S, Correia KF, Calafat AM, et al. Predictors and Variability of Urinary Paraben Concentrations in Men and Women, Including before and during Pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(11):1538–43. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1104614.

Gomez E, Pillon A, Fenet H, Rosain D, Duchesne MJ, Nicolas JC, et al. Estrogenic Activity of Cosmetic Components in Reporter Cell Lines: Parabens, UV Screens, and Musks. J Toxic Environ Health A. 2005;68(4):239–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390590895054.

Okubo T, Yokoyama Y, Kano K, Kano I. ER-dependent estrogenic activity of parabens assessed by proliferation of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells and expression of ERα and PR. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39(12):1225–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6915(01)00073-4.

Nguyen VK, Kahana A, Heidt J, et al. A comprehensive analysis of racial disparities in chemical biomarker concentrations in United States women, 1999-2014. bioRxiv 2019:746867. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/746867

Pycke BFG, Geer LA, Dalloul M, Abulafia O, Halden RU. Maternal and fetal exposure to parabens in a multiethnic urban U.S. population. Environ Int. 2015;84:193–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2015.08.012.

Krause M, Klit A, Jensen MB, et al. Sunscreens: are they beneficial for health? An overview of endocrine disrupting properties of UV-filters. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):424–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01280.x.

Calafat AM, Wong L-Y, Ye X, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Concentrations of the Sunscreen Agent Benzophenone-3 in Residents of the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(7):893–7. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.11269.

Wang J, Pan L, Wu S, Lu L, Xu Y, Zhu Y, et al. Recent Advances on Endocrine Disrupting Effects of UV Filters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13080782.

Schlecht C, Klammer H, Jarry H, Wuttke W. Effects of estradiol, benzophenone-2 and benzophenone-3 on the expression pattern of the estrogen receptors (ER) alpha and beta, the estrogen receptor-related receptor 1 (ERR1) and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) in adult ovariectomized rats. Toxicology. 2004;205(1-2):123–30.

Han C, Lim Y-H, Hong Y-C. Ten-year trends in urinary concentrations of triclosan and benzophenone-3 in the general U.S. population from 2003 to 2012. Environ Pollut. 2016;208:803–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.11.002.

Summers P. Sunscreen Use: Non-Hispanic Blacks Compared With Other Racial and/or Ethnic Groups. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(7):863–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2011.172.

Bellavia A, Zota AR, Valeri L, James-Todd T. Multiple mediators approach to study environmental chemicals as determinants of health disparities. Environ Epidemiol. 2018;2(2):e015. https://doi.org/10.1097/EE9.0000000000000015.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ayanna Coburn-Sanderson and Marlee Quinn for their assistance.

Funding

This work was funded by grants from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences R01ES026166 and P30ES000002, along with the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health T42OH008416.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent:

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key Terms: Phthalates, phenols, prenatal, pregnancy, race/ethnicity

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, M., Mita, C., Bellavia, A. et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy and Prenatal Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals Commonly Used in Personal Care Products. Curr Envir Health Rpt 8, 98–112 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-021-00317-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-021-00317-5