Abstract

Purpose

This short review aims to cover the more recent and promising developments of carbon-11 (11C) labeling radiochemistry and its utility in the production of novel radiopharmaceuticals, with special emphasis on methods that have the greatest potential to be translated for clinical positron emission tomography (PET) imaging.

Methods

A survey of the literature was undertaken to identify articles focusing on methodological development in 11C chemistry and their use within novel radiopharmaceutical preparation. However, since 11C-labeling chemistry is such a narrow field of research, no systematic literature search was therefore feasible. The survey was further restricted to a specific timeframe (2000–2016) and articles in English.

Results

From the literature, it is clear that the majority of 11C-labeled radiopharmaceuticals prepared for clinical PET studies have been radiolabeled using the standard heteroatom methylation reaction. However, a number of methodologies have been developed in recent years, both from a technical and chemical point of view. Amongst these, two protocols may have the greatest potential to be widely adapted for the preparation of 11C-radiopharmaceuticals in a clinical setting. First, a novel method for the direct formation of 11C-labeled carbonyl groups, where organic bases are utilized as [11C]carbon dioxide-fixation agents. The second method of clinical importance is a low-pressure 11C-carbonylation technique that utilizes solvable xenon gas to effectively transfer and react [11C]carbon monoxide in a sealed reaction vessel. Both methods appear to be general and provide simple paths to 11C-labeled products.

Conclusion

Radiochemistry is the foundation of PET imaging which relies on the administration of a radiopharmaceutical. The demand for new radiopharmaceuticals for clinical PET imaging is increasing, and 11C-radiopharmaceuticals are especially important within clinical research and drug development. This review gives a comprehensive overview of the most noteworthy 11C-labeling methods with clinical relevance to the field of PET radiochemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

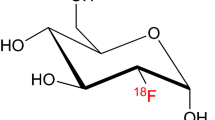

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a highly sensitive imaging modality that can provide in vivo quantitative information of biological processes at a biochemical level [1]. PET relies upon the administration of a chemical probe, often called a radiopharmaceutical, that is labeled with a short-lived positron-emitting radionuclide [e.g. 11C (t 1/2 = 20.4 min) and 18F (t 1/2 = 109.7 min)]. Several PET radiopharmaceuticals have been developed for imaging applications, predominantly within oncology [2] and neuroscience [3, 4]. The development of novel radiopharmaceuticals requires multiple considerations, where aspects like radionuclide selection, labeling position, metabolic stability, precursor synthesis, radiolabeling procedure, automation, quality control and regulatory affairs all have to be considered [5, 6].

Carbon-11 is one of the most useful radionuclides for PET chemistry, since its introduction into a biologically active molecule has minimal effects on the (bio)chemical properties of the compound [7, 8]. In addition, there is a vast literature on carbon-based chemistry that can be consulted in the development of radiosynthetic procedures with carbon-11. Moreover, the short half-life of 11C allows for longitudinal in vivo studies with repeated injections in the same subject (patient or animal) and on the same experimental day. Although the advances in 11C chemistry have enabled the preparation of a great number of radiolabeled molecules, there are still relatively few that have been applied for the direct preparation of novel radiopharmaceuticals for PET. The present review will provide an overview of the most recent and promising developments within carbon-11 chemistry since year 2000.

General considerations in radiopharmaceutical chemistry

A few general comments are required to provide a context for a discussion of PET radiopharmaceutical production [2, 5]. First of all, the radionuclides used in PET emit high-energy radiation and, therefore, the traditional hands-on manipulations used in synthetic chemistry are not feasible. Thus, in order to avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, radiolabeling is performed in fully automated and pre-programmed synthesis modules housed inside lead-shielded fume hoods (hot-cells). One could say that radiochemistry, in particular that with 11C, is a hybrid science between organic chemistry and engineering. Time is another factor of major importance in PET chemistry. A radiopharmaceutical used in PET is typically synthesized, purified, formulated and analyzed within a timeframe of roughly 2–3 physical half-lives of the employed radionuclide. For example, to obtain 11C-labeled radiopharmaceutical in optimal radiochemical yield (RCY), a compromise has to be made between the chemical yield and the radioactive decay. The chemical yield of a reaction is thus not as important as the obtained radioactivity of the target compound at end of synthesis. Furthermore, since only trace amount of the radiolabeling synthon is used in PET, the amount of the non-radioactive reagents is in large excess, which implies that the reaction follows pseudo first-order kinetics. By consequence, small impurities in reagents or solvents may have a significant influence on the reaction outcome. The radiochemist has to further consider the specific activity (SA), which is a measure of the radioactivity per unit mass of the final radiolabeled compound. Since high SA is often required in neuroreceptor imaging studies to avoid saturation of the receptor system, the methods that are highlighted in this review are all non-carrier-added nature.

Carbon-11 chemistry

Carbon-11 is commonly generated via the 14N(p, α)11C nuclear reaction. The reaction is performed by high-energy proton bombardment of a cyclotron target containing nitrogen gas with small amounts a second gas. [11C]Carbon dioxide (11CO2) and [11C]methane (11CH4), are formed, when either small amounts oxygen or hydrogen are present in the cyclotron target. Sometimes, these simple primary precursors are used directly as labeling agents (e.g. 11CO2), but more often they are converted via on-line synthetic pathways into more reactive species before being used in 11C-labeling reactions. However, several reactive 11C-labeled precursors have been developed over the years [8], but the 11C-precursors that will be discussed in this review are displayed and highlighted in Fig. 1.

11C-methylation reaction

By far, the most common method in modern carbon-11 chemistry is heteroatom methylation using the methylating agents [11C]methyl iodide (11CH3I) [9, 10] or [11C]methyl triflate (11CH3OTf) [11, 12]. This reaction can either be performed using a traditional vial-based approach or alternatively using solid support (“on-cartridge” [13] or “in-loop” [14] methods), which is very convenient from an automation prospective. A majority of the 11C-labeled radiopharmaceuticals that are used on a regular basis, with a few exceptions, are thus produced by these two methylating agents. However, these methylating agents are sluggishly reactive towards arylamines. Especially difficult are substrates where the aryl group in a primary arylamine electron density has been further reduced by an electron-withdrawing group. In such situations, the more reactive methylating agent, 11CH3OTf, may even fail to react. However, Pike and co-workers presented a method that utilized inorganic bases (e.g. Li2O) paired with DMF to permit methylation of a wide range of arylamines using 11CH3I at room temperature [15]. Moreover, in a recent study, the research group of Billard described the application of 11CO2 as a C1 building block for the catalytic methylation of amines [16]. Importantly, this one-pot approach eliminates the time-consuming preparation of the active methylating agent. The proposed mechanism is outlined in Table 1. In brief, an appropriate amine precursor, initially traps 11CO2 to form complex 1, which is reduced in two-steps with ZnCl2/iPr and PhSiH3, to furnish the expected methylamine. It was realized that the 11CO2 trapping was dependent on the basicity of the amine in use, varying between 65 and 80%. A large number of substrates, including the well-established radioligand, [11C]PIB [17], was obtained in acceptable yields (Table 1).

In recent years, the application of 11CH3I in transition-metal-mediated reactions has become more widespread for 11C-labeling of radiopharmaceuticals [18, 19]. Figure 2 shows a brief overview of compounds labeled via Pd-mediated 11C-methylation. Two radioligands for the serotonin transporter, [p-methyl-11C]MADAM [20] and [11C]5-methyl-5-nitroquipazine [21], as well as a novel radioligand for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor [22] (nAChRs) was methylated using the transition-metal-mediated reaction. [11C]A-85,380 displayed favorable in vivo properties for quantification of the nAChRs in living brain [23]. The nAChRs represents major neurotransmitter receptor responsible for various brain functions, and changes in the density of nAChRs have been reported in various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease [24]. Another example is the radiosynthesis of the 15R-[11C]TIC methyl ester, a prostacyclin receptor radioligand, which was the first radioligand approved for investigation in humans [25, 26]. The same radioligand was later used to image variations in organic anion-transporting polypeptide function in the human hepatobiliary transport system [27].

Two of the most applied cross-coupling reactions in radiochemical synthesis today are the Stille and Suzuki reactions, where organotin and organoborane compounds function as starting materials, respectively, and 11CH3I as a coupling partner. A wide variety of functional groups such as amino, hydroxyl, or carboxylate are tolerated in these reactions and protective groups are usually not required. One unfortunate drawback with Stille coupling is, however, the inherent toxicity of the organotin reagent. Because of the regulatory aspects associated with radiopharmaceuticals that are to be used in human subjects, the less toxic organoborate substrates are usually preferred. As an alternative route to 11C-methylated arenes, Kealey and co-workers describe a convenient two-step Pd-mediated cross-coupling of 11CH3I with organozinc reagents (Scheme 1) [28]. The Nagishi-type reaction was used to synthesize a series of simple arenes in excellent yields. The same protocol was finally applied in the radiosynthesis of an mGluR5 radioligand, [11C]MPEP [29]. Even though organozinc reagents are known to be moisture sensitive, it is much likely, that in the near future, Nagishi cross-coupling reaction will be considered a good alternative to the established protocols.

Enolates are a class of carbon centered nucleophiles that shortly may have a major importance in the radiopharmaceutical community. To generate an active enolate, a strong base, such as alkyl lithium or lithium diisopropylamide is typically needed. Using lithium bases to remove a α-proton is not always adequate because of their moisture sensitivity. However, in 2010, two methods for the synthesis of 11C-labeled arylpropionic acid derivatives have been presented [30, 31]. The rapid sp3–sp3 11C-methylation reaction relied on the formation of benzylic enolates, using either sodium hydride or tetrabutylammonium fluoride as base (Scheme 2). The reaction proceeds smoothly under mild conditions. However, until recently, the 11C-methylated product formed under these conditions was obtained in low enantiomeric purity. The use of chiral phase-transfer catalyst has enabled enantioselective synthesis of the amino acid, [11C]l-alanine, in high enantioselective purity [enantiomeric excess (ee) of 90%] [32].

Moreover, this year, our group presented a novel (carbonyl)cobalt-mediated, and microwave-assisted, carbonylative protocol for the direct preparation of 11C-labeled aryl methyl ketones using 11CH3I as the labeling agent [33]. The method uses CO2(CO)8 as a combined aryl halide activator and carbon monoxide source for the carbonylation reaction. The method was used to label a set of functionalized (hetero)arenes with yields ranging from 22 to 63% (Scheme 3).

11CO2-fixation reaction

[11C]Carbon dioxide is in itself a highly attractive starting material for radiolabeling, since it is produced directly in the cyclotron. However, due to low chemical reactivity, the direct incorporation of CO2 into organic molecules poses a significant challenge. High pressures, high temperatures or catalysts are commonly required to activate the molecule. The traditional method for 11CO2 “fixation” is the Grignard reaction, which involves the conversion of alkyl or aryl magnesium halides to [11C]carboxylic acids. However, Grignard reagents require great care and the rigorous exclusion of atmospheric moisture and CO2 during storage and manipulation. To overcome these limitations, two independent research groups presented what arguably can be viewed as the most ground-breaking advance in the field of carbon-11 chemistry since 11CH3I was introduced in the early 1970s. The innovative method, that was inspired by the recent advances in “green chemistry” and reported in 2009, uses sub-milligram amounts of precursor compound, reacts at low temperature (typically room temperature), for 1–3 min reaction time and does not require advanced technical equipment [34, 35]. To overcome the low reactivity of CO2, organic amines such as DBU or BEMP act as organomediators by activating CO2 prior to the covalent bond formation [36, 37]. The first report on 11CO2 fixation was on the synthesis of 11C-labeled carbamates. However, the scope of the method was later broadened to include [11C]ureas and [11C]oxazolidinones (Scheme 4) [38], via the formation of an 11C-labeled isocyanate or carbamoyl anhydride intermediate. A number of drug-like molecules have been prepared using this methodology in recent years (2009–2016, see Fig. 3). These includes, the carbonyl analogue radioligand of [11C-methyl]AR-A014418, a compound developed for imaging of synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) [39]. However, unfortunately, the in vivo evaluations of AR-A014418 revealed an undesirably low brain uptake [40]. Moreover, two potent and irreversible fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitors, [11C]PF-04457845 [41] and [11C]CURB [42], have also been prepared. The latter, [11C]CURB, have recently been translated to a clinical setting for reginal quantification of FAAH activity in human brain [43]. Furthermore, the reversible monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) radioligand, [11C]SL25.1188, previously prepared using the technical demanding [11C]phosgene approach, was radiolabeled in high yield via 11CO2-fixation [44, 45]. This radioligand was recently translated for human PET imaging [46].

Proposed pathways of 11C-labeled urea and carbamates via 11CO2-fixation chemistry [37]

Later, on a related subject, Dheere and co-workers presented a further refinement to the methodology to obtain [11C]ureas from less reactive amines, such as anilines [47, 48]. Once again, DBU was used to trap 11CO2 in solution, but in this case, it was shown that treatment of the carbamate anion intermediate (5) with Mitsunobu reagents, DBAD and PBu3, provided the corresponding asymmetric ureas in high radiochemical conversion (Scheme 5).

In the interest of expanding the scope of 11CO2 as a feedstock in radiochemical synthesis, copper-mediated approaches to carboxylic acids and their derivatives have been described [49, 50]. In the most recent example, the combination of Cu(I) with boronic esters enabled CO2 activation in the presence of a soluble fluoride additive and an organic base. In this reaction, the use of TMEDA was found to be crucial for obtaining high radiochemical yields, an observation likely explained by its dual action as both a trapping agent for 11CO2 and a ligand for the copper catalyst. A variety of functional groups were tolerated under optimized conditions, and the generated 11C-carboxylic acids could be further converted into either amines or esters, as exemplified in the one-pot two-step preparation of a candidate radioligand for the oxytocin receptor.

Carbonylation reactions using 11CO

[11C]Carbon monoxide (11CO) has many attractive features as a synthon for PET radiochemistry, including its facile production [51, 52] and high versatility in transition-metal-mediated carbonylation reactions [53–56]. The widespread use of 11CO in radiosynthetic chemistry was until recently hampered by its poor reactivity. Several solutions have been introduced to overcome the above shortcomings, both from a technical and chemical point of view [57–60]. A breakthrough was reported in 1999, where Kihlberg and co-workers introduced a method wherein 11CO was allowed to react in a small autoclave under high solvent pressure (>350 Bar) [61]. The high-pressure reactor methodology exhibited nearly quantitative 11CO trapping efficiency and high radiochemical yield. Even though this method has exemplified the importance of 11CO as a labeling precursor it has not gained broad adoption in the PET radiochemistry community. This can partly be attributed to the overall complexity of the autoclave system and the relatively high level of service needed to maintain the system operational. Moreover, the repeated use of an integrated stainless steel reactor may infer issues related to transition metal build up over time, which is problematic in reaction development and system validation.

In recent years, the development of low-pressure techniques has been in focus. In 2012, an efficient protocol was reported by Eriksson and co-workers, in which 11C-carbonylation reactions were achieved without the need for high-pressure equipment [62]. The high solubility of xenon gas in organic solvents was exploited as an effective way of transferring 11CO into a sealed standard disposable reaction vial (1 ml) without significant pressure increase. The utility of the method was exemplified by 11C-labeling of amides, ureas, and esters. The use of disposable glass reaction vessels eliminates carry over issues associated with the high-pressure autoclave system, thus simplifying the transition to clinical applications. Recently, three reports were published using the same 11CO transfer protocol (Fig. 4). Windhorst et al. produced three 11C-labeled acryl amide radioligands for in vivo PET imaging of the tissue transglutaminase (TG2) enzyme [63]. Moreover, with the “xenon-method” as the synthesis platform, the Uppsala-group presented two novel approaches to 11C-carbonyl labeled compounds. Firstly, a new multicomponent reaction for 11C-labeling of sulfonyl carbamates was described [64]. The method was further applied as a synthetic tool for the in vivo evaluation of an angiotensin II receptor subtype 2 (AT2R) agonist. Secondly, a method to access 11C-labeled alkyl amides via a thermally-initiated radical reductive dehalogenative approach [65]. One of the restrictions of transition-metal-mediated reactions is the competing β-hydride elimination of the resulting metal-substrate intermediate, which precludes the use of alkyl electrophiles containing β-hydrogen. This unfortunate competing reaction is non-excitant for radical pathways. A series of un-activated alkyl iodides was successfully converted into the corresponding alkyl amide in good RCY, including the radiosynthesis of an 11β-HSD1 inhibitor.

Specific Pd-complexes have also been shown to trap 11CO at ambient pressure and without the need for any high-pressure equipment [66, 67]. XantPhos, a hindered bidentate phosphine ligand, in combination with palladium (µ-cinnamyl) chloride dimer were found to be excellent for promoting 11C-carbonylation reactions. Notably, in this study it was discovered that, depending on the palladium-ligand complex in use, different 11CO trapping efficiency was observed (Table 2). The reaction proceeds smoothly at close to atmospheric pressure with aryl halides or triflates as substrates using simple disposable glass vials. This method was recently also applied in the preparation of well-known D2 radioligand, [11C]raclopride, but with the carbon-11 labeled in the more metabolically stable carbonyl group (Fig. 4) [68]. Interestingly, in a direct comparison between ([11C]methyl)raclopride (produced using the standard 11C-methylation approach) and ([11C]carbonyl)raclopride, both radioligands showed similar in vivo properties with regards to quantitative outcome measurements, radiometabolite formation and protein binding.

The protocol was further improved by Andersen and co-workers, where pre-generated (Aryl)Pd(I)Ln oxidative addition complexes were utilized as precursors for the following 11C-carbonylation reaction [69]. This is exemplified in the preparation of [11C- carbonyl]raclopride in Scheme 6. The isolated complexes, (Aryl)Pd(I)Ln, have already undergone the potentially challenging oxidative addition step before their employment in carbonylative 11C-labeling. In this case, Pd-XantPhos complexes appeared to be among the most reactive precursors, although, electron-deficient aryl precursors demanded Pd-P(t-Bu)3 to prevent aryl scrambling with phosphine ligand. The simplicity of these low-pressure techniques, and especially the “xenon-method” delivery protocol, may offer a potential for being widely adopted in radiopharmaceutical research and development.

As mentioned previously, one restriction with transition-metal-mediated reactions is the competing β-hydride elimination. However, in contrast to Pd or Rh catalyst, nickel has been known to suppress the β-hydride elimination reaction. In the light of this, Rahman and co-workers recently reported the first successful use of nickel-mediated carbonylative cross-coupling of non-activated alkyl iodides using 11CO at ambient pressure [70]. The best conditions identified in this study made use of a nickel(0) precatalyst, Ni(COD)2, in the presence of bathophenantroline as ligand (Table 3). Six model compounds were successfully radiolabeled in acceptable to good yields. However, more data is required to establish if the method is suitable of preparing more complex molecules.

Other recent advances in carbon-11 chemistry

Hydrogen cyanide is well established as a versatile precursor in PET radiopharmaceutical chemistry [71–73], and its involvement in metal-mediated cyanation of aryl (pseudo)halides is well documented [74, 75]. A limitation of such reactions is that they require rather harsh conditions, such as high temperature, long reaction times, and inorganic bases (e.g. KOH), which reduces the substrate scope. Recently, a novel method was reported describing near instantaneous, room temperature Pd-mediated coupling of [11C]HCN to aryl halides or triflates [76]. The method is based on sterically hindered biaryl phosphine ligands (Table 4) that facilitate rapid transmetalation with [11C]HCN and reductive elimination of aryl nitriles at ambient temperature. A wide variety of (hetero)arenes and drug-like molecules were radiolabeled in high yields, including the κ-opioid receptor radioligand [11C]LY2795050 (Fig. 5). Moreover, two known antidepressants were also 11C-labeled in this study. This further illustrates the usefulness of the current method in the preparation of radiopharmaceuticals.

Carbon disulfide, the sulfur analogue of carbon dioxide, has recently been synthesized on-line from 11CH3I using either P2S5 and elemental sulfur (S8) at elevated temperatures in excellent yields [77, 78]. Due to the weaker C=S bond CS2 is considered more reactive than CO2. Moreover, CS2 reacts very rapidly with many primary amines at room temperature to form the dithiocarbamate salts, which in turn, upon treatment with a suitable alkylating reagent will give the corresponding thiocarbamates. Heating, on the other hand, induces rearrangement to form the symmetrical thiourea (Scheme 7). Some model compounds were radiolabeled using this protocol in near quantitative yields. Finally, a progesterone receptor agonist, Tanaproget, was also produced in high RCY (Fig. 5).

Lastly, an improved, mild synthesis of [11C]formaldehyde have opened up new to carbon-11 labeled radiopharmaceuticals [79]. The treatment of trimethylamine N-oxide with 11CH3I at room temperature gave 11CH2O in a one-pot reaction. This novel preparation has been utilized by a number of groups to generate new exciting compounds (Fig. 5) [80, 81]. In addition, since [11C]formaldehyde was reported already in 1972 [82], there are other molecules previously reported in the literature that may now be synthesized in a simplified fashion using this protocol.

Final remarks

The increasing importance of PET in drug development and clinical research has motivated researchers to initiate programs directly dedicated to development of new radiolabeling methods. This review summarizes some of the most recent and promising strategies to obtain carbon-11 labeled products. In the past two decades, and well before this, efforts have brought to bear an impressive range of methods for 11C-radiochemistry. However, there are still issues to be addressed. Take for example, the heteroatom 11C-methylation reaction, which is now considered as an established method by the broader radiochemical community. Why is this? The main reason is the access to dedicated commercially available radiochemical equipment for this radiochemistry. Consequently, to streamline new methodologies, and make them widely available, new radiochemical equipment is needed. A possible approach to attack the problem could be to develop radiosynthesis equipment with a higher flexibility. A fundamental question is if microscale technology (microfluidic or microreactor) can provide a breakthrough in radiochemistry? Its compact design, flexible attributes, and its suitability for automation make microscale technology an ideal platform for performing the rapid radiolabeling reactions required for PET. So far, efforts made to adapt microscale technology for PET radiolabeling purposes have focused on proof-of-principle studies and to illustrate the advantages associated with the technology and significant further development is needed for the technology to reach its full potential. Although the authors recognize the importance of microreactor technologies, other technical approaches towards the development of more flexible radiochemical synthesis equipment are equally attractive at this point. Regardless of which direction is taken in the future, we firmly believe that a stronger collaboration between radiochemists and technical engineers is vital for succeeding in the development of the next generation of PET radiochemistry equipment.

Finally, radiochemistry is the foundation for PET imaging. By broadening the spectrum of radiochemical reactions within clinical PET radiochemistry, radiochemists will not only be able to increase the number of compounds that can be labeled with carbon-11 but also provide an increased opportunity to label a given compound in different positions.

References

Phelps ME (1991) PET: a biological imaging technique. Neurochem Res 16:929–940

Ametamey SM, Honer H, Schubiger PA (2008) Molecular imaging with PET. Chem Rev 108:1501–1516

Halldin C, Gulyas B, Langer O, Farde L (2001) Brain radioligands—state of the art and new trends. J Nucl Med 45:139–152

Pike VW (2009) PET radiotracers: crossing the blood-brain barrier and surviving metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci 30:431–440

Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R, Gee AD (2008) Synthesis of 11C, 18F, 15O, and 13N radiolabels for positron emission tomography. Angew Chem Int Ed 47:8998–9033

Pike VW (2016) Considerations in the development of reversibly binding PET radioligands for brain imaging. Curr Med Chem 23:1818–1869

Antoni G (2015) Development of carbon-11 labeled PET tracers—radiochemical and technological challenges in a historic perspective. J Label Compd Radiopharm 58:65–72

Scott P (2009) Methods for the incorporation of carbon-11 to generate radiopharmaceuticals for PET imaging. Angew Chem Int Ed 48:6001–6004

Långström B, Lundqvist H (1976) The preparation of 11C-methyl iodide and its use in the synthesis of 11C-methyl-L-methionine. Int Appl Radiat Isot 27:357–363

Larsen P, Ulin J, Dahlström K, Jensen M (1997) Synthesis of [11C]iodomethane by iodination of [11C]methane. Appl Radiat Isot 48:153–157

Jewett DM (1992) A simple synthesis of [11C]methyl triflate. Int Appl Radiat Isot 43:1383–1385

Någren K, Müller L, Halldin C, Swahn C, Lehikoinen P (1995) Improved synthesis of some commonly used PET radioligands by the use of [11C]methyl triflate. Nucl Med Biol 22:235–239

Pascali C, Bogni A, Iwata R, Cambie M, Bombardieri E (2000) [11C]Methylation on a C18 Sep-Pak cartridge: a convenient way to produce [N-methyl-11C]choline. J Label Compd Radiopharm 43:195–203

Wilson AA, Garcia A, Jin L, Houle S (2000) Radiotracer synthesis from [11C]-iodomethane: a remarkedly simple captive solvent method. Nucl Med Biol 27:529–532

Cai L, Xu R, Guo X, Pike VW (2012) Rapid room-temperature 11C-methylation of arylamines with [11C]methyl iodide promoted by solid inorganic-bases in DMF. Eur J Org Chem 1303–1310

Liger F, Eijsbouts T, Cadarossanesaib F, Tourvieille C, Le Bars D, Billard T (2015) Direct [11C]methylation of amines from [11C]CO2 for the synthesis of PET radiotracers. Eur J Chem Org 6434–6438

Klunk W, Engler H, Norberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt D, Bergström M, Savitcheva I, Huang G, Estrada S, Ausén B, Debnath M, Baretta J, Price J, Sandell J, Lopresti B, Wall B, Koivisto P, Antoni G, Mathis CA, Långström B (2004) Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh compound-B. Ann Neurol 55:306–319

Pretze M, Große-Gehling P, Mamat C (2011) Cross-coupling as a versatile tool for the preparation of PET radiotracers. Molecules 16:1129–1165

Doi H (2015) Pd-mediated cross-couplings using [11C]methyl iodide: groundbreaking labeling methods in 11C radiochemistry. J Label Compd Radiopharm 58:73–85

Tarkiainen J, Vercouillie J, Emond P, Sandell J, Hiltunen J, Frangin Y, Guilloteau D, Halldin C (2001) Carbon-11 labeling of MADAM in two different positions: a highly selective PET radioligand for the serotonin transporter. J Label Compd Radiopharm 44:1013–1023

Sandell J, Halldin C, Sovago J, Chow Y, Gulyás B, Yu M, Emond P, Någren K, Guilloteau D, Farde L (2002) PET examination of [11C]5-methyl-6-nitroquipazine, a radioligand for visualization of the serotonin transporter. Nucl Med Biol 29:651–656

Karimi F, Långström B (2002) Synthesis of 3-[(2S)-azetidin-2-ylmethoxy]-5-[11C]-methylpyridine, an analogue of A-85380, via a Stille coupling. J Label Compd Radiopharm 45:423–434

Iida Y, Ogawa M, Ueda M, Tominaga A, Kawashima H, Magata Y, Nishiyama S, Tsukada H, Mukai T, Saji H (2004) Evaluation of 5-11C-Methyl-A-85380 as an imaging agent for PET investigations of brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Nucl Med 45:878–884

Paterson D, Nordberg A (2000) Neuronal nicotinic receptors in the human brain. Prog Neurobiol 61:75–111

Björkman M, Doi H, Resul B, Suzuki M, Noyori R, Watanabe Y, Långström B (2000) Synthesis of a 11C-labeled prostaglandin F2α analogue using an improved method for the Stille reaction with [11C]methyl iodide. J Label Compd Radiopharm 43:1327–1334

Suzuki M, Doide H, Hosoya T, Långström B, Watanabe (2004) Rapid methylation on carbon frameworks leading to the synthesis of a PET tracer capable of imaging a novel CNS-type prostacyclin receptor in living human brain. TrAC Trends Anal Chem 23:595–607

Takashima T, Kitamura S, Wada Y, Tanaka M, Shigihara Y, Ishii H, Ijuin R, Shiomi S, Nakae T, Watanabe Y, Cui Y, Doi H, Suzuki M, Maeda K, Kusuhara H, Sugiyama Y, Watanabe Y (2012) PET imaging-based evaluation of hepatobiliary transport in humans with (15R)-11C-TIC-Me. J Nucl Med 53:741–748

Kealey S, Passchier J, Huiban M (2013) Negishi coupling reactions as a valuable tool for [11C]methyl-arene formation; first proof of principle. Chem Comm 49:11326–11328

Hamill T, Krause S, Ryan C, Bonnefous C, Govek S, Seiders J, Gibson R, Sanabria S, Riffel K, Eng W, King C, Yang X, Green M, O’Malley S, Hargreaves R, Burns D (2005) Synthesis, characterization, and first successful monkey imaging studies of metabortropic glutamate receptor subtype 5 (mGluR5) PET radiotracer. Synapse 56:205–216

Takashima-Hirano M, Shukuri M, Takashima T, Goto M, Wada Y, Watanabe Y, Onoe H, Doi H, Suzuki M (2010) General method for the 11C-labeling of 2-arylpropionic acids and their esters: construction of a PET tracer library for a study of biological events involved in COXs expression. Chem Eur J 16:4250–4258

Kato K, Kikuchi T, Nengaki N, Arai T, Zhang M (2010) Tetrabutylammonium fluoride-promoted α-[11C]methylation of α-arylesters: a simple and robust method for the preparation of ibuprofen. Tetrahedron Lett 51:5908–5911

Filp U, Pekošak A, Poot A, Windhorst B (2016) Enantioselective synthesis of carbon-11 labeled l-alanine using phase transfer catalysis of Schiff bases. Tetrahedron 72:6551–6557

Dahl K, Schou M, Halldin C (2016) Direct and efficient (carbonyl) cobalt-mediated aryl acetylation using [11C]methyl iodide. Eur J Org Chem 2775–2777

Hooker JM, Reibel A, Hill S, Schueller M, Fowler JS (2009) One-pot, direct incorporation of [11C]CO2 into carbamates. Angew Chem Int Ed 48:3482–3485

Wilson A, Garcia A, Houle S, Vasdev N (2010) Direct fixation of [11C]-CO2 by amines: formation of [11C-carbonyl]-methylcarbamates. Org Biomol Chem 8:428–432

Rotstein B, Liang S, Placzek M, Hooker JM, Gee AD, Dollé F, Wilson A, Vasdev N (2016) 11CO bond made easily for positron emission tomography radiopharmaceuticals. Chem Soc Rev 45:4708–4726

Rotstein B, Liang S, Holland J, Lee TL, Hooker JM, Wilson A, Vasdev N (2013) 11CO2 fixation: a renaissance in PET radiochemistry. Chem Comm 49:5621–5629

Wilson A, Garcia A, Houle S, Sadovski O, Vasdev N (2011) Synthesis and application of isocyanates radiolabeled with carbon-11. Chem Eur J 17:259–264

Vasdev N, Garcia A, Stableford W, Young A, Meyer J, Houle S, Wilson AA (2005) Synthesis an ex vivo evaluation of carbon-11 labeled N-(4-methoxybenzyl)-N′-(5-Nitro-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)urea ([11C]AR-A014418): a radiolabeled glycogen synthase kinase-3β specific inhibitor for PET studies. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 15:5270–5273

Hicks J, Parkes J, Sadovski O, Tong J, Houle S, Vasdev N, Wilson A (2012) Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of [11C-carbonyl]PF-04457845 for neuroimaging of fatty acid amide hydrolase. Nucl Med Biol 40:740–746

Hicks J, Parkes J, Sadovski O, Tong J, Houle S, Vasdev N, Wilson A (2012) Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of [11C-carbonyl]PF-04457845 for neuroimaging of fatty acid amide hydrolase. Nucl Med Biol 40:740–746

Wilson AA, Hicks J, Sadovski O, Parkes J, Tong J, Houle S, Fowler C, Vasdev N (2013) Radiosynthesis and evaluation of [11C-carbonyl]-labeled carbamates as fatty acid amide hydrolase radiotracer for positron emission tomography. J Med Chem 56:201–209

Boileau I, Rusjan P, Williams B, Mansouri E, Mizrahi R, De Luca V, Johnson D, Wilson AA, Houle S, Kish S, Tong J (2015) The fatty acid amide C385A variant affects brain binding of the positron emission tomography tracer [11C]CURB. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35:1827–1835

Vasdev N, Sadovski O, Garcia A, Dollé F, Meyer J, Houle S, Wilson A (2011) Radiosynthesis of [11C]SL25.1188 via [11C]CO2 fixation for imaging of monoamine oxidase B. J Label Compd Radiopharm 54:678–680

Saba W, Valette H, Peyronnea M, Bramoulle Y, Coulon C, Curet O, George P, Dolle F, Bottlaender M (2010) [11C]SL25.1188, a new reversible radioligand to study the monoamine oxidase type B with PET: preclinical characterization in nonhuman primate. Synapse 64:61–69

Rusjan P, Wilson AA, Miler L, Fan I, Mizrahi R, Houle S, Vasdev N, Meyer J (2014) Kinetic modeling of the monoamine oxidase B radioligand [11C]SL25.1188 in human brain imaging with positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34:883–889

Dheere A, Yusuf N, Gee AD (2013) Rapid and efficient synthesis of [11C]ureas via incorporation of [11C]CO2 into aliphatic and aromatic amines. Chem Comm 49:8193–8195

Dheere A, Bongarzone S, Taddei C, Yan R, Gee AD (2015) Synthesis of 11C-labeled symmetrical ureas via rapid incorporation of [11C]CO2 into aliphatic and aromatic amines. Synlett 26:2257–2260

Riss P, Lu S, Telu S, Aigbirhio F, Pike VW (2012) CuI-catalyzed 11C carboxylation of boronic acid esters: a rapid and convenient entry to 11C-labeled carboxylic acids, esters, and amides. Angew Chem Int Ed 51:2698–2702

Rotstein B, Hooker JM, Woo J, Lee TL, Brady T, Liang S, Vasdev N (2014) Synthesis of [11C]bexarotene by Cu-mediated [11C]carbon dioxide fixation and preliminary PET imaging. ACS Med Chem Lett 5:668–672

Zeisler SK, Nader M, Oberdorfer F (1997) Conversion of no-carrier-added [11C]carbon dioxide to [11C]carbon monoxide on molybdenum for the synthesis of 11C-labeled aromatic ketones. Appl Radiat Isot 48:1091–1095

Dahl K, Itsenko O, Rahman O, Ulin J, Sjöberg C, Sandblom P, Larsson L, Schou M, Halldin C (2015) An evaluation of a high-pressure 11CO carbonylation apparatus. J Labell Compd Radiopharm 58:220–225

Brennführer A, Neumann H, Beller M (2009) Palladium-catalyzed carbonylation reactions of aryl halides and related compounds. Angew Chem Int Ed 48:4114–4133

Långström B, Itsenko O, Rahman O (2007) [11C]carbon monoxide, a versatile and useful precursor in labelling chemistry for PET-ligand development. J Labell Compd Radiopharm 50:794–810

Kealey S, Gee AD, Miller PW (2014) Transition metal mediated [11C]carbonylation reactions: recent advances and applications. J Labell Compd Radiopharm 57:195–201

Rahman O (2015) [11C]Carbon monoxide in labeling chemistry and positron emission tomography tracer development: scope and limitations. J Labell Compd Radiopharm 58:86–98

Andersson Y, Långström B (1995) Synthesis of 11C-labeled ketones via carbonylative couplings reaction using [11C]carbon monoxide. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1:287–289

Lidström P, Kihlberg T, Långström B (1997) [11C]carbon monoxide in the palladium-mediated synthesis of 11C-labeled ketones. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1:2701–2706

Kealey S, Miller PW, Long N, Plisson C, Martarello L, Gee AD (2009) Copper(I) scorpionate complexes and their application in palladium-mediated [11C]carbonylation reactions. Chem Comm 25:3696–3698

Dahl K, Schou M, Ulin J, Sjöberg C, Farde L, Halldin C (2015) 11C-Carbonylation reaction using gas-liquid segmented microfluidics. RSC Adv 5:88886–88889

Kihlberg T, Långström B (1999) Biologically active amides using palladium-mediated reactions with aryl halide and [11C]carbon monoxide. J Org Chem 64:9201–9205

Eriksson J, van den Hoek J, Windhorst AD (2012) Transition metal mediated synthesis using [11C]CO at low pressure—a simplified method for 11C-carbonylation. J Labell Compd Radiopharm 55:223–228

van der Wildt B, Wilhelmus M, Bijkerk J, Haveman L, Kooijman E, Schuit R, Bol J, Jongenelen C, Lammertsma A, Drukarch B, Windhorst AD (2016) Development of carbon-11 labeled acryl amides for selective PET imaging of active tissue transglutaminase. Nucl Med Biol 43:232–242

Stevens M, Chow S, Estrada S, Eriksson J, Asplund V, Orlova A, Mitran B, Antoni G, Larhed M, Odell L (2016) Synthesis of 11C-labeled sulfonyl carbamates through a multicomponent reaction employing sulfonyl azides, alcohols, and [11C]CO. ChemistryOpen 5:566–573

Chow S, Odell L, Eriksson J (2016) Low-pressure radical 11C-aminocarbonylation of alkyl iodides through thermal initiation. Eur J Org Chem 5980–5989

Dahl K, Schou M, Amini N, Halldin C (2013) Palladium-mediated [11C]carbonylation at atmospheric pressure: a general method using xantphos as supporting ligand. Eur J Org Chem 1228–1231

Dahl K, Schou M, Rahman O, Halldin C (2014) Improved yields for the palladium-mediated 11C-carbonylation reaction using microwave technology. Eur J Org Chem 307–310

Rahman O, Takano A, Amini N, Dahl K, Kanegawa N, Långström B, Farde L, Halldin C (2015) Synthesis of ([11C]carbonyl)raclopride and a comparison with ([11C]methyl)raclopride in a monkey PET study. Nucl Med Biol 11:893–898

Andersen T, Friis S, Audrain H, Nordeman P, Antoni G, Skrydstrup T (2015) Efficient 11C-carbonylation of isolated aryl palladium complexes for PET: application to challenging radiopharmaceutical synthesis. J Am Chem Soc 137:1548–1555

Rahman O, Långström B, Halldin C (2016) Alkyl halides and [11C]CO in nickel-mediated cross-coupling reactions: successful use of alkyl electrophiles containing β hydrogen atom in metal-mediated [11C]carbonylation. ChemistrySelect 1:2498–2501

Matsson O, Persson J, Axelsson BS, Långström B, Fang A, Westaway KC (1996) Using incoming group 11C/14C kinetic isotope effects to model the transition states for the SN2 reaction between para-substituted benzyl chloride and labeled cyanide ion. J Am Chem Soc 118:6350–6354

Antoni G, Långström B (1992) Synthesis of 11C-labeled α, β-saturated nitriles. Int Appl Radiat Isot 43:903–905

Thorell J, Stone-Elander S, Elander N (1992) Use of microwave cavity to reduce reaction times in radiolabelling with [11C]cyanide. J Labell Compd Radiopharm 31:207–217

Andersson Y, Långström B (1995) Transition metal-mediated reactions using [11C]cyanide in synthesis of 11C-labeled aromatic compounds. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1:1395–1400

Ponchant M, Hinnen F, Demphel S, Crouzel C (1997) [11C]Copper(I) cyanide: a new radioactive precursor for 11C-cyanation and functionalization of haloarenes. Appl Radiat Isot 48:755–762

Lee HG, Milner P, Placzek M, Buchwald SL, Hooker JM (2015) Virtually instantaneous, room-temperature [11C]-cyanation using biaryl phosphine Pd(0) complexes. J Am Chem Soc 137:648–651

Miller PW, Bender D (2012) [11C]Carbon disulfide: a versatile reagent for PET radiolabelling. Chem Eur J 18:433–436

Haywood T, Kealey S, Sánchez-Cabezas S, Hall J, Allott L, Smith G, Plisson C, Miller PW (2015) Carbon-11 radiolabelling of organosulfur compounds: 11C synthesis of the progesterone receptor agonist tanaproget. Chem Eur J 21:9034–9038

Hooker JM, Schönberger M, Schieferstein H, Fowler J (2008) A simple, rapid method for the preparation of [11C]formaldehyde. Angew Chem Int Ed 47:5989–5992

Popkov A, Itsenko O (2015) An asymmetric approach to the synthesis of a carbon-11 labeled gliotransmitter d-serine. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 304:455–458

Neelamegam R, Hellenbrand T, Schroeder F, Wang C, Hooker JM (2014) Imaging evaluation of 5HT2C agonist, [11C]WAY-163909 and [11C]vabicaserin, formed by Pictet-Spengler cyclization. J Med Chem 57:1488–1494

Christman D, Crawford E, Friedkin M, Wolf AP (1972) Detection of DNA synthesis in intact organisms with positron-emission [methyl-11C]thymidine. Proc Natl Acad Sci 69:988–992

Acknowledgements

The authors thank members of the PET group at Karolinska Institutet.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

KD declares that he has no conflict of interest. CH declares that he has no conflict of interest. MS declares the he is an employee and shareholder at AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

K Dahl: Literature Search and Review, Manuscript Writing. C Halldin: Content planning and Editing. M Schou: Content planning and Editing.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahl, K., Halldin, C. & Schou, M. New methodologies for the preparation of carbon-11 labeled radiopharmaceuticals. Clin Transl Imaging 5, 275–289 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40336-017-0223-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40336-017-0223-1