Abstract

Background

With more than two-thirds of the US population overweight or obese, the obesity epidemic is a major threat for population health and the financial sustainability of the healthcare service. Whether, and to what extent, effective prevention interventions may offer the opportunity to ‘bend the curve’ of rising healthcare costs is still an object of debate.

Objective

This study evaluates the potential economic impact of a set of prevention programmes, including education, counselling, long-term drug treatment, regulation (e.g. of advertising or labelling) and fiscal measures, on national healthcare expenditure and use of healthcare services in the USA.

Study Design and Method

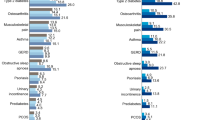

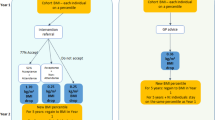

The study was carried out as a retrospective evaluation of alternative scenarios compared with a ‘business as usual’ scenario. An advanced econometric approach involving the use of logistic regression and generalized linear models was used to calculate the number of contacts with key healthcare services (inpatient, outpatient, drug prescriptions) and the associated cost. Analyses were carried out on the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (1997–2010).

Results

In 2010, prevention interventions had the potential to decrease total healthcare expenditure by up to $US2 billion. This estimate does not include the implementation costs. The largest share of savings is produced by reduced use and costs of inpatient care, followed by reduced use of drugs. Reduction in expenditure for outpatient care would be more limited. Private insurance schemes benefit from the largest savings in absolute terms; however, public insurance schemes benefit from the largest cost reduction per patient. People in the lowest income groups show the largest economic benefits.

Conclusion

Prevention interventions aimed at tackling obesity and associated risk factors may produce a significant decrease in the use of healthcare services and expenditure. Savings become substantial when a long-term perspective is taken.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

OECD. OECD obesity update 2014. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2014.

Kitahara CM, Flint AJ, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Bernstein L, Brotzman M, MacInnis RJ, et al. Association between Class III obesity (BMI of 40–59 kg/m2) and Mortality: a pooled analysis of 20 prospective studies. PLoS Med. 2014;11(7):e1001673.

Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;25(9):88.

CDC. Obesity at a Glance 2011 halting the epidemic by making health easier. Atlanta: CDC; 2011.

James PT, Jackson-Leach R, Mhurchu CN, Kalamara E, Shayeghi M, Rigby NJ, et al. Overweight and obesity (body mass index). In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Comparative quantification of health risks. Geneva: WHO; 2004.

Withrow D, Alter DA. The economic burden of obesity worldwide: a systematic review of the direct costs of obesity. Obes Rev. 2011;12(2):131–41.

Finkelstein EA, Di Bonaventura M, Burgess SM, Hale BC. The costs of obesity in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:971–6.

Obama M. Let’s move! Raising a healthier generation of kids. Child Obes. 2012;8(1):1.

OECD. Obesity and the economics of prevention: fit not fat. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2010.

Cecchini M, Sassi F, Lauer JA, Lee YY, Guajardo-Barron V, Chisholm D. Tackling of unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and obesity: health effects and cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2010;376(9754):1775–84.

Cutler DM, Glaeser EL, Shapiro JM. Why have Americans become more obese? J Econ Perspect. 2003;17(3):93–118.

Sassi F, Cecchini M, Lauer J, Chisholm D. Improving lifestyle, tackling obesity: the health and economic impact of prevention strategies. OECD Health Working Paper 48. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2009.

Merkur S, Sassi F, McDaid D. Promoting health, preventing diseases: is there an economic case?. Copenhagen: WHO Europe; 2014.

Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(1):74–86.

Shaw FE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Rein AS. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: opportunities for prevention and public health. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):75–82.

Saloner B, Sabik L, Sommers BD. Pinching the poor? Medicaid cost sharing under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1177–80.

Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG. Public health interventions for addressing childhood overweight: analysis of the business case. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):411–5.

Ormond BA, Spillman BC, Waidmann TA, Caswell KJ, Tereshchenko B. Potential national and state medical care savings from primary disease prevention. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(1):157–64.

Haas JS, Phillips KA, Gerstenberger EP, Seger AC. Potential savings from substituting generic drugs for brand-name drugs: medical expenditure panel survey, 1997–2000. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(11):891–7.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. “Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: survey background”. Available at: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp. Accessed 20 Nov 2014.

Office of the Actuary of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National health expenditures accounts: methodology paper, 2011 definitions, sources, and methods. Baltimore; 2001.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Using appropriate price indices for analyses of healthcare expenditures or income across multiple years. Available at: http://meps.ahrq.gov/about_meps/Price_Index.shtml. Accessed 11 Apr 2015.

Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20:461–94.

Andersen CK, Andersen K, Kragh-Sorensen P. Cost function estimation: the choice of a model to apply to dementia. Health Econ. 2000;9:397–409.

Austin PC, Ghali WA, Tu JV. A comparison of several regression models for analysing cost of CABG surgery. Stat Med. 2003;22:2799–815.

Lipscomb, J, Ancukiewicz M, Parmigiani G, Hasselblad V, Samsa G, Matchar DB. Predicting the cost of illness: a comparison of alternative models applied to stroke. Med Decis Making. 1998;18(Suppl.):S39–56.

Montez-Rath M, Christiansen CL, Ettner SL, Loveland S, Rosen AK. Performance of statistical models to predict mental health and substance abuse cost. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:1–11.

Box GEP, Cox DR. An analysis of transformations. J Royal Stat Soc. series B 1964;26(2):211–252.

Trasande L, Chatterjee S. The impact of obesity on health service utilization and costs in childhood. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(9):1749–54.

Akaike H, A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans autom Control. 1974;AC-19:716–723.

Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in Model Selection. Sociol Meth Res. 2004;33:61–304.

James WPT, Jackson-Leach R, Mhurchu CN, Kalamara E, Shayeghi M, Rigby NJ, Nishida C, Rodgers A. Overweight and obesity (high body mass index). In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Comparative quantification of health risks. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004.

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60.

DeSalvo KB, Fan VS, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Predicting mortality and healthcare utilization with a single question. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(4):1234–46.

Fan VS, Au D, Heagerty P, Deyo RA, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Validation of case-mix measures derived from self-reports of diagnoses and health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(4):371–80.

Fan VS, Maciejewski ML, Liu CF, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Comparison of risk adjustment measures based on self-report, administrative data, and pharmacy records to predict clinical outcomes. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method. 2006;6:21–36.

Huntley AL, Johnson R, Purdy S, Valderas JM, Salisbury C. Measures of multimorbidity and morbidity burden for use in primary care and community settings: a systematic review and guide. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(2):134–41.

Maciejewski ML, Liu CF, Derleth A, McDonell M, Anderson S, Fihn SD. The performance of administrative and self-reported measures for risk adjustment of Veterans Affairs expenditures. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(3):887–904.

WHO. Interventions on diet and physical activity: what works. Geneva: WHO; 2009.

Cabrera Escobar MA, Veerman JL, Tollman SM, Bertram MY, Hofman KJ. Evidence that a tax on sugar sweetened beverages reduces the obesity rate: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1072.

Wee CC, Phillips RS, Legedza AT, Davis RB, Soukup JR, Colditz GA, Hamel MB. Health care expenditures associated with overweight and obesity among US adults: importance of age and race. Am J Public Health. 200;95(1):159–65.

Thompson D, Brown JB, Nichols GA, Elmer PJ, Oster G. Body mass index and future healthcare costs: a retrospective cohort study. Obes Res. 2001;9(3):210–8.

Kuehn BM. Cutting Medicare costs will require multipronged approach. JAMA. 2013;309(13):1334–5.

Kuehn BM. Economist: It’s time for tough choices on US health costs. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2469–70.

Healthcare.gov website. Preventive health services for adults. US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2014. https://www.healthcare.gov/what-are-my-preventive-care-benefits/. Accessed 10 Sept 2014.

Dolor RJ, Schulman KA. Financial incentives in primary care practice: the struggle to achieve population health goals. JAMA. 2013;310(10):1031–2.

Bernard D, Cowan C, Selden T, Cai L, Catlin A, Heffler S. Reconciling medical expenditure estimates from the MEPS and NHEA, 2007. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(4):E1–E20.

Cawley J, Rizzo JA, Haas K. Occupation-specific absenteeism costs associated with obesity and morbid obesity. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(12):1317–24.

Loeppke R, Taitel M, Haufle V, Parry T, Kessler RC, Jinnett K. Health and productivity as a business strategy: a multiemployer study. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):411–28.

Gortmaker SL, Cheung LW, Peterson KE, Chomitz G, Cradle JH, Dart H, Fox MK, Bullock RB, Sobol AM, Colditz G, Field AE, Laird N. Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: eat well and keep moving. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(9):975–83.

Luepker RV, Perry CL, Osganian V, Nader PR, Parcel GS, Stone EJ, Webber LS. The child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH). J Nutr Biochem. 1998;9:525–34.

Perry CL, Lytle L, Feldman H, Nicklas T, Stone E, Zive M. Effects of the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) on fruit and vegetable intake. J Nutr. 1998;30(6):354–60.

Reynolds KD, Franklin FA, Binkley D, Raczynski JM, Harrington KF, Kirk KA, Person S. Increasing the fruit and vegetable consumption of fourth-graders: results from the high 5 project. Prev Med. 2000;30(4):309–19.

Sorensen G, Stoddard A, Hunt MK, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Avrunin JS, et al. The effects of a health promotion-health protection intervention on behavior change: the WellWorks Study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(11):1685–90.

Sorensen G, Stoddard A, Peterson K, Cohen N, Hunt MK, Stein E, Palombo R, Lederman R. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption through worksites and families in the Treatwell 5-a-day study. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(1):54–60.

Sorensen G, Thompson B, Glanz K, Feng Z, et al. Work site-based cancer prevention: primary results from Working Well Trial. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(7):939–47.

Emmons KM, Linnan LA, Shadel WG, Marcus B, Abrams DB. The Working Healthy Project: a worksite health-promotion trial targeting physical activity, diet and smoking. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(7):545–55.

Buller DB, Morrill C, Taren D, Aickin M, Sennott-Miller L, Buller MK, et al. Randomized trial testing the effect of peer education at increasing fruit and vegetable intake. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(17):1491–500.

Ockene IS, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Merriam PA, Hurley TG, Saperia GM. Effect of training and a structured office practice on physician-delivered nutrition counseling: the Worcester-area trial for counseling in hyperlipidemia (WATCH). Am J Prev Med. 1996;12(4):252–8.

Herbert JR, Ebbeling CB, Ockene IS, Ma Y, Rider L, Merriam PA, et al. A dietician-delivered group nutrition program leads to reductions in dietary fat, serum cholesterol and body weight: the Worcester-area trial for counselling in hyperlipidaemia (WATCH). J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(5):544–52.

Pritchard DA, Hyndman J, Taba F. Nutritional counselling in general practice: a cost-effective analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:311–6.

Chou S, Rasha I, Grossman M. Fast-food restaurant advertising on television and its influence on childhood obesity. J Law Econ. 2008;51:599–618.

OFCOM. Changes in the nature and balance of television food advertising to children: A review of HFSS Advertising restrictions. London: Ofcom; 2008.

Variyam JN, Cawley J. Nutrition labels and obesity. Cambridge: NBER Working Paper No. 11956; 2006.

Variyam JN. Do nutrition labels improve dietary outcomes? Health Econ. 2008;17:695–708.

Conflict of interest statement

MC and FS report no financial or other relationships relevant to the subject of the article.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed in this abstract are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD or its member countries.

MC conceived the study, designed and conducted the analyses, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript; FS contributed to the design of the analyses and the drafting of the report. The sole responsibility for the content of this document lies with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cecchini, M., Sassi, F. Preventing Obesity in the USA: Impact on Health Service Utilization and Costs. PharmacoEconomics 33, 765–776 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0301-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0301-z