Abstract

Introduction

Uncertainty influences the amount of risk in decision making, and is typically related to clinical benefit, value for money, affordability, and/or adoption/diffusion of the technology (e.g., drug, device, procedure, etc.). Although evidence-based review processes within each stage of the technology lifecycle have been implemented to minimize uncertainty, high-quality information addressing that related to orphan and ultra-orphan drugs is often unavailable. The role that patients, as experts in their disease, may play in providing such information has yet to be fully explored.

Objective

The objective of this systematic review was to identify existing and proposed opportunities for patients with rare diseases and their families to provide input aimed at reducing decision uncertainties throughout the lifecycle of an orphan or ultra-orphan drug.

Methods

A comprehensive review of published and gray literature describing roles for patients and families in activities related to orphan and ultra-orphan drugs was conducted. In addition, the websites of regulatory and centralized reimbursement decision-making bodies in the top 22 OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries by gross domestic product (GDP) were scanned to identify current opportunities for patients with rare diseases in both stages. The websites of umbrella patient organizations for rare diseases in these countries were also scanned. These roles were then mapped onto a matrix to determine the stage in the technology lifecycle and types of uncertainties they directly or indirectly addressed.

Results

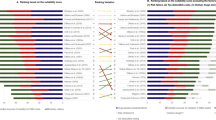

Across the 22 countries, nine roles for patients within regulatory related processes were identified, with at least one in each country. These roles were not specific to patients with rare diseases. Similarly, six different opportunities for patient input in centralized drug review processes were identified, all of which applied to patients, in general, rather than just those with rare diseases. ‘Real-world’ examples of patient involvement explicitly related to rare diseases centered around 11 different themes. Seven fell within the research and development or clinical trial stages of a drug’s lifecycle. Of the remaining four, three were associated with education and advocacy. All of the proposed roles identified focused on greater involvement in (1) the design and conduct of clinical trials, or (2) the ‘valuation’ of evidence during reimbursement decision making. When mapped onto the matrix of decision uncertainties, almost all of the existing and proposed roles addressed ‘clinical benefit’. Roles for patients in reducing ‘value for money’, affordability, or adoption/diffusion uncertainties were mainly indirect, and a result of patient involvement in activities aimed at generating information on clinical benefit, which is then used to inform discussions around these uncertainties.

Conclusions

While patient involvement in activities that directly address uncertainties in clinical benefit may not be ‘rare’, opportunities for reducing those related to ‘value for money’, affordability, and adoption/diffusion remain scarce.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Canadian Drug Expert Committee final recommendation—plain language version: eltrombopag olamine (Revolade-GlaxoSmithKline Inc.). Indication: chronic immune (idiopathic) thrombocytopenic purpura. Common Drug Review (CDR). Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2011.

CEDAC final recommendation: eculizumab (Soliris-Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). Indication: paroxysmal noctural hemoglobinuria. Common Drug Review (CDR). Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2010.

CEDAC final recommendation on reconsideration and reasons for recommendation: pegvisomant (Somavert-Pfizer Canada Inc.). Common Drug Review (CDR). Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2006.

CEDAC final recommendation: eltrombopag olamine (Revolade-GlaxoSmithKline Inc.). Indication: chronic immune (idiopathic) thrombocytopenic purpura. Common Drug Review (CDR). Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2011.

CEDAC final recommendation: tocilizumab (Actemra-Hoffmann-La Roche). New indication: arthritis, systemic juvenile idiopathic. Common Drug Review (CDR). Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2012.

About the Common Drug Review. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2014.

Elliott KC, Dickson M. Distinguishing risk and uncertainty in risk assessments of emerging technologies. In: Zülsdorf T, Coenen C, Ferrari A, Fiedeler U, Milburn C, Wienroth M, editors. Quantum engagements: social reflections of nanoscience and emerging technologies. Heidelberg: AKA; 2011, p. 165–76.

Riabacke A. Managerial decision making under risk and uncertainty. IAENG Int J Comput Sci. 2006;32(4), (IJCS_32_4_12). http://www.iaeng.org/IJCS/issues_v32/issue_4/IJCS_32_4_12.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2014.

Meekings KN, Williams CS, Arrowsmith JE. Orphan drug development: an economically viable strategy for biopharma R&D. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17(13–14):660–4.

Garattini S. Time to revisit the orphan drug law. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(2):113.

Kesselheim AS, Myers JA, Avorn J. Characteristics of clinical trials to support approval of orphan vs nonorphan drugs for cancer. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2320–6.

RARE facts and statistics. Aliso Viejo: The Global Genes Project; 2012.

Cetel JS. Disease-branding and drug-mongering: could pharmaceutical industry promotional practices result in tort liability? Seton Hall Law Rev. 2012;42(2):643–702.

Clarke JT. Is the current approach to reviewing new drugs condemning the victims of rare diseases to death? A call for a national orphan drug review policy. CMAJ. 2006;174(2):189–90.

Carmichael LE. Gene therapy. North Mankato: ABDO Publishing; 2014. p. 76.

Schey C, Milanova T, Hutchings A. Estimating the budget impact of orphan medicines in Europe: 2010–2020. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:62.

Picavet E, Dooms M, Cassiman D, Simoens S. Drugs for rare diseases: influence of orphan designation status on price. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9(4):275–9.

Orphanet website Canadian entry point. [Ottawa]: Orphanet; 2014. http://www.orpha.net/national/CA-EN/index/homepage/. Accessed 31 May 2014

Hughes DA, Tunnage B, Yeo ST. Drugs for exceptionally rare diseases: do they deserve special status for funding? QJM. 2005;98(11):829–36.

Initial draft discussion document for a Canadian orphan drug regulatory framework. Ottawa: Health Canada, Office of Legislative and Regulatory Modernization; 2012.

The patient’s voice in the evaluation of medicines: how patients can contribute to assessment of benefit and risk. London: European Medicines Agency (EMA); 2013.

Patients and consumers. London: European Medicines Agency (EMA); 2014.

Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: in search of a method. Evaluation. 2002;8(2):157–81.

Stafinski T, McCabe CJ, Menon D. Funding the unfundable: mechanisms for managing uncertainty in decisions on the introduction of new and innovative technologies into healthcare systems. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(2):113–42.

Consumer input to the Australian Drug Evaluation Committee (ADEC). Summary evaluation of 2002–04 pilot project. Manuka (ACT): Consumers’ Health Forum of Australia; 2006.

Towards a strategic science plan. Ottawa: Health Canada, Drugs and Health Products; 2009.

Spooner A. Implementing the new pharmacovigilance legislation. Dublin: Irish Medicines Board; 2011.

Intanza intradermal 9ug dose influenze vaccine for persons 18–59 years of age: data sheet. Wellington: New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority (MEDSAFE); 2014.

The Patient Reported Outcomes (PRO) Consortium. Silver Spring: US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 2010.

Framework on the interaction between the EMEA and patients’ and consumers’ organisations. London: European Medicines Agency (EMEA); 2006.

Consultation workshop report on patient involvement strategy. Ottawa: Health Canada. Office of Consumer and Public Involvement and Best Medicines Coalition (BMC); 2002.

Regulatory transparency and openness. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2009.

Report an adverse drug reaction. Reykjavik: Lyfjastofnun/Icelandic Medicines Agency (IMA); 2014.

The Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency: annual report fy 2008. Tokyo: Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA); 2008.

Pharmacovigilance. Oslo: Statens Legemiddelverk/Norwegian Medicines Agency; 2012.

The voice of the patient: a series of reports from FDA’s Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative. Silver Spring: US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 2014.

Patient and consumer participation pool. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2011.

Public involvement framework. Ottawa: Health Canada. Health Products and Food Branch; 2005.

About the patient representative program. Silver Spring: US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 2014.

FAQs: who can be a patient representative? Silver Spring: US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 2014.

Korean pharmacopoeia. Chungcheongbuk-do (Korea): Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; 2014.

Medicines Classification Committee. Public consultation on agenda items. Wellington: New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority (MEDSAFE); 2014.

Bere N. Lifecycle of a new medicinal product—with emphasis on pharmacovigilance. London: European Medicines Agency (EMA); 2013.

FDA working with patients to explore benefit/risk: opportunities and challenges. Silver Spring (MD): US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 2012.

Reporting problems. Canberra: Australian Government. Department of Health. Therapeutic Goods Administration; 2014.

Adverse reaction and medical device problem reporting. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2012.

Safety information: how to report a problem. Wellington: MEDSAFE: New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority; 2013.

Pharmacovigilance. Bern: Swissmedic: Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products; 2014.

Reporting serious problems to FDA. Silver Spring: US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); 2014.

Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Health, Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC); 2014.

Obtaining consumer comments on submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee meetings. Canberra: Australian Government. Department of Health. Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC); 2014.

Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (Version 4.3). Canberra: Australian Government. Department of Health, Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC); 2008.

Germany—pharmaceutical. Lawrenceville: International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR); 2009.

Fukuda T. Use of economic evaluation for policy making in Japan [conference presentation]. Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research in Asia: what is next? ISPOR 16th European Congress in Dublin, Nov 5, 2013; 2013. http://www.ispor.org/congresses/Dublin1113/presentations/ISPOR20131105-fukuda.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2014.

Ngorsuraches S, Meng W, Kim BY, Kulsomboon V. Drug reimbursement decision-making in Thailand, China, and South Korea. Value Health. 2012;15(1 Suppl):S120–5.

Liste des specialites (LS) [List of pharmaceutical specialties (LS)]. Berne: Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH); 2013.

Interim process and methods of the Highly Specialised Technologies Programme. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2013.

Innovation pass pilot: a consultation on proposals for an innovation pass pilot. London: Department of Health, Medicines Pharmacy and Industry Group; 2009.

Templates/guidance for submission. Glasgow: Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC); 2014.

All Wales Medicines Strategy Group: about us. Vale of Glamorgan: All Wales Medicines Strategy Group (AWMSG); 2014.

Patient input. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2014.

GUIDE—patient group input to the Common Drug Review at CADTH. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2014.

Pharmaceuticals Pricing Board legislation. Helsinki: Finland Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; 2013.

Garau M, Mestre-Ferrandiz J. Access mechanisms for orphan drugs: a comparative study of selected European countries. London: Office of Health Economics; 2009.

Barham L. Orphan medicines: special treatment required? London: 2020health.org; 2012.

Franken M, le Polain M, Cleemput I, Koopmanschap M. Similarities and differences between five European drug reimbursement systems. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(4):349–57.

Sorenson C, Drummond M, Kanavos P. Ensuring value for money in health care: the role of health technology assessment in the European Union. Copenhagen: World Health Organization/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2008.

Guidelines for funding applications to PHARMAC. Wellington: New Zealand Government, Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC); 2010.

Highly Specialised Technologies Evaluation Committee. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2013.

Mavris M, Le CY. Involvement of patient organisations in research and development of orphan drugs for rare diseases in Europe. Mol Syndromol. 2012;3(5):237–43.

Polich GR. Rare disease patient groups as clinical researchers. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17(3–4):167–72.

Boon W, Broekgaarden R. The role of patient advocacy organisations in neuromuscular disease R&D—the case of the Dutch neuromuscular disease association VSN. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20(2):148–51.

Wastfelt M, Fadeel B, Henter JI. A journey of hope: lessons learned from studies on rare diseases and orphan drugs. J Intern Med. 2006;260(1):1–10.

Rabeharisoa V. The struggle against neuromuscular diseases in France and the emergence of the “partnership model” of patient organisation. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(11):2127–36.

Rabeharisoa V, Callon M. The involvement of patients’ associations in research. Int Soc Sci J. 2002;54(171):57–63.

PRO RETINA Germany eV. Aachen (Germany): PRO RETINA Deutschland e.V. http://www.pro-retina.de/ (2014). Accessed 31 May 2014.

Nierse CJ, Abma TA, Horemans AM, van Engelen BG. Research priorities of patients with neuromuscular disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(5):405–12.

Davila-Seijo P, Hernandez-Martin A, Morcillo-Makow E, de Lucas R, Dominguez E, Romero N, et al. Prioritization of therapy uncertainties in dystrophic Epidermolysis bullosa: where should research direct to? An example of priority setting partnership in very rare disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:61.

Linertova R, Serrano-Aguilar P, Posada-de-la-Paz M, Hens-Perez M, Kanavos P, Taruscio D, et al. Delphi approach to select rare diseases for a European representative survey. The BURQOL-RD study. Health Policy. 2012;108(1):19–26.

Wood J, Sames L, Moore A, Ekins S. Multifaceted roles of ultra-rare and rare disease patients/parents in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18(21–22):1043–51.

Parkinson K. The involvement of patients in developing clinical guidelines [abstract]. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7(Suppl 2):A13.

Bacon CJ, Hall CA, Shy ME. The rare diseases clinical research network contact registry for the inherited neuropathies consortium. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2013;18:S9.

Pattacini C, Rivolta GF, Di PC, Riccardi F, Tagliaferri A, Haemophilia Centres Network of Emilia-Romagna Region. A web-based clinical record ‘xl’Emofilia’ for outpatients with haemophilia and allied disorders in the Region of Emilia-Romagna: features and pilot use. Haemophilia. 2009;15(1):150–8.

Frost JH, Massagli MP, Wicks P, Heywood J. How the Social Web Supports patient experimentation with a new therapy: the demand for patient-controlled and patient-centered informatics. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008;2008:217–21.

Mallbris L, Nordenfelt P, Bjorkander J, Lindfors A, Werner S, Wahlgren CF. The establishment and utility of Sweha-Reg: a Swedish population-based registry to understand hereditary angioedema. BMC Dermatol. 2007;7:6.

TREAT-NMD: serving the neuromuscular community. Newcastle upon Tyne: TREAT-NMD Neuromuscular Network; 2014.

Terry SF, Terry PF, Rauen KA, Uitto J, Bercovitch LG. Advocacy groups as research organizations: the PXE International example. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(2):157–64.

de Blieck EA, Augustine EF, Marshall FJ, Adams H, Cialone J, Dure L, et al. Methodology of clinical research in rare diseases: development of a research program in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL) via creation of a patient registry and collaboration with patient advocates. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(2):48–54.

Pierri P. A route map for the patients journey [abstract]. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7(Suppl 2):A40.

Ayme S, Kole A, Groft S. Empowerment of patients: lessons from the rare diseases community. Lancet. 2008;371(9629):20080614–20.

Keeling P. Role of the opportunity to test index in integrating diagnostics with therapeutics. Personal Med. 2006;3(4):399–407.

Pypops U. Patient perspective on CT Involvement: Are they listening to my needs? [abstract]. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7(Suppl 2):A39.

Gupta S, Bayoumi AM, Faughnan ME. Rare lung disease research: strategies for improving identification and recruitment of research participants. Chest. 2011;140(5):1123–9.

Carroll R, Antigua J, Taichman D, Palevsky H, Forfia P, Kawut S, et al. Motivations of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension to participate in randomized clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2012;9(3):348–57.

Sussex J, Rollet P, Garau M, Schmitt C, Kent A, Hutchings A. A pilot study of multicriteria decision analysis for valuing orphan medicines. Value Health. 2013;16(8):1163–9.

History of the Australian Drug Evaluation Committee 1963–2009. Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration; 2010.

Australian public assessment report for sunitinib. Proprietary product name: Sutent. Sponsor: Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd. Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods Administration; 2011.

Harvey K. Consumer input in Medicines Australia’s code of conduct review. Conversation. 2012 Apr 16. http://theconversation.com/consumer-input-in-medicines-australias-code-of-conduct-review-6370. Accessed 4 Dec 2014.

Scientific advice/protocol assistance: experience and impact of patient involvement. London: EURORDIS: Rare Diseases Europe/European Medicines Agency (EMA); 2013.

Benefit-risk evaluation. Ottawa: Health Canada, Drugs and Health Products; 2007.

Consultation: draft guidance for industry—submission of risk management plans and follow-up commitments. Ottawa: Health Canada, Drugs and Health Products; 2014.

General information: pharmacovigilance. Reykjavik: Lyfjastofnun/Icelandic Medicines Agency (IMA); 2014.

Laws and regulations. Reykjavik: Lyfjastofnun/Icelandic Medicines Agency (IMA); 2014.

New Zealand regulatory guidelines for medicines. Part A: when is an application for approval of a new or changed medicine required? 6.15 ed. Wellington: New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority (MEDSAFE); 2011.

PHIS pharma profile template: Norway, Version 1. [n.s.]: Vienna: Pharmaceutical Health Information System (PHIS). 2011. http://www.legemiddelverket.no/English/the-norwegian-health-care-system-and-pharmaceutical-system/Documents/NO%20PHIS%20Pharma%20Profile%202011_links%20updated%20March%202014.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2014.

Regulations: regulation (EU) no 1235/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 2010. Off J Eur Union. 2010;L348:1–16.

Good pharmacovigilance practices. London: European Medicines Agency (EMA); 2014.

Austria—pharmaceutical. Lawrenceville: International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR); 2009.

Leopold C, Habl C. Pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement information: Austria. Vienna: Pharmaceutical Pricing and Reimbursement Information (PPRI); 2008.

Medicinal products and health care in Austria: facts and figures 2013. Vienna: Pharmig; 2013.

Erstattungskodex-EKO [Code of reimbursement-Austria]. Stand 1 ed. Wien: Haputverband der osterreichischen Sozialversicherungstrager; 2013.

Rules of procedure for publishing the code of reimbursement according to 351g ASVG. [n.s.]: Vienna: Austrian Federation of Social Insurance Institutions/Osterreichische Sozialverischerung; 2007.

Guillaume P, Moldenaers I, Bulte S, Debruyene H, Devriese S, Kohn L, Pierart J, Vinck I. Optimisation of the operational processes of the Special Solidarity Fund. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre; 2010.

Reimbursement of medicines. Copenhagen: Sundhedsstyrelsen/Danish Health and Medicines Authority; 2012.

Application for basic reimbursement status and reasonable wholesale price for a medicinal product subject to special licence. For applications by a patient or a pharmacy on behalf of the patient. [n.s.]: Laakkeiden Hintalautakunta/Government of Finland. Helsinki: Pharmaceuticals Pricing Board; 2011.

Guidelines for preparing a health economic evaluation. [n.s.]: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Helsinki: Pharmaceuticals Pricing Board; 2011.

Temporary authorisations for use (ATU). [n.s.]: Paris: Agence Francaise de Securite Sanitaire des Produits de Sante; 2001.

Meyer F. Orphan drugs assessment and reimbursement: the situation in France. Toronto: Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders (CORD); 2009.

Denis A, Simoens S, Fostier C, Mergaert L, Cleemput I. Policies for orphan diseases and orphan drugs. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE); 2009.

Creation of a process for the exchange of knowledge between member states and European authorities on the scientific assessment of the clinical added value for orphan medicines. Reference: EAHC/2010/Health/05 ed. Brussels: European Commission. Executive Agency for Health and Consumers (EAHC); 2011.

Pelen F. Reimbursement and pricing of drugs in France: an increasingly complex system. HEPAC Health Econ Prev Care. 2000;3:20–3.

Remuzat C, Toumi M, Falissard B. New drug regulations in France: what are the impacts on market access? Part 1—overview of new drug regulations in France. J Market Access Health Policy. 2013;1:1–9.

Rochaix L, Xerri B. National Authority for Health: France. Issue Brief (Commonw. Fund). 2009;58:1–9.

Stafinski T, Menon D, Philippon D, McCabe C. Health technology funding decision-making processes around the world: the same yet different. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(6):475–95.

Fulda CB. A revolution of reimbursement in Germany. Jones Day; 2011. http://www.jonesday.com/revolution_of_reimbursement/. Accessed 4 Dec 2014.

Ordinance on the placing on the market of unauthorised medicinal products for compassionate use (Ordinance on Medicinal Products for Compassionate Use—AMHV). [n.s.]: Berlin: Bundesministerium fur Gesundheit/German Federal Minister of Health; 2010.

Kavanagh C, Diamond D, O’Gorman M. Ireland. Dublin: Arthur Cox; 2014.

Bakowska M, Berekmeri-Varro R, Biro H, Brandt S, Bruyndonckx A, Casanueva AEA. Pricing and reimbursement handbook. 1st ed. Geneva, USA: Baker & McKenzie; 2011.

Taruscio D, Capozzoli F, Frank C. Rare diseases and orphan drugs. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2011;47(1):83–93.

C. Hable and F. Bachner. Initial investigation to assess the feasibility of a coordinated system to access orphan medicines. Vienna: European Commission, Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry; European Medicine Information Network (EMINet); Gesundheit Osterreich GmbH; 2011.

Access to treatments that aren’t on the lists (NPPA). Wellington: New Zealand Government, Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC); 2014.

PHIS pharma profile: Norway, Version 1. [n.s.]: Vienna: Pharmaceutical Health Information System (PHIS); 2011.

Disposiciones generales: Ministerio de Sanidad y Politica Social. Boletin Oficial del Estado. 2009;174 (Sec. 1):60904–13.

Switzerland—pharmaceutical. Lawrenceville: International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR); 2011.

Process for advising on the feasibility of implementing a patient access scheme. Interim. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Patient Access Schemes Liaison Unit; 2009.

Komlos D. Focusing on patients in drug development. Life Sci Connect. 2013 Dec 20. pp. 1–5. http://lsconnect.thomsonreuters.com/patient-focused-drug-development/. Accessed 8 Dec 2014.

Bignami F, Kent AJ, Lipucci di PM, Meade N. Participation of patients in the development of advanced therapy medicinal products. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2011;54(7):839–42.

Crompton H. Mode 2 knowledge production: evidence from orphan drug networks. Sci Public Policy. 2007;34(3):199–211.

Smith WB, McCaslin IR, Gokce A, Mandava SH, Trost L, Hellstrom WJ. PDE5 inhibitors: considerations for preference and long-term adherence. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(8):768–80.

Licht C, Ardissino G, Ariceta G, Beauchamp J, Cohen D, Greenbaum L, et al. An observational, non-interventional, multicenter, multinational registry of patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (AHUS): methodology [abstract]. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28(8):1571.

Acknowledgments

The work reported in this paper was made possible by an Emerging Team Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research on “Developing Effective Policies for Managing Technologies for Rare Diseases”.

Author contributions

D. Menon made a substantial contribution to the conception and planning of the work that led to this manuscript, to the interpretation of the data, to critical revision and final approval of the manuscript, and is the overall guarantor of the work.

T. Stafinski made a substantial contribution to the conception and planning of the work that led to this manuscript, to the analysis and interpretation of the data, to drafting, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

A. Dunn made a substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the data, to critical revision and final approval of the manuscript.

H. Short made a substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the data, to critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

None of the authors has any financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Menon, D., Stafinski, T., Dunn, A. et al. Involving Patients in Reducing Decision Uncertainties Around Orphan and Ultra-Orphan Drugs: A Rare Opportunity?. Patient 8, 29–39 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0106-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0106-8