Abstract

Nociplastic pain is defined as pain due to sensitization of the nervous system, without a sufficient underlying anatomical abnormality to explain the severity of pain. Nociplastic pain may be manifest in various organ systems, is often perceived as being more widespread rather than localized and is commonly associated with central nervous system symptoms of fatigue, difficulties with cognition and sleep, and other somatic symptoms; all features that contribute to considerable suffering. Exemplified by fibromyalgia, nociplastic conditions also include chronic visceral pain, chronic headaches and facial pain, and chronic musculoskeletal pain. It has been theorized that dysfunction of the endocannabinoid system may contribute to persistent pain in these conditions. As traditional treatments for chronic pain in general and nociplastic pain in particular are imperfect, there is a need to identify other treatment options. Cannabis-based medicines and medical cannabis (MC) may hold promise and have been actively promoted by the media and advocacy. The medical community must be knowledgeable of the current evidence in this regard to be able to competently advise patients. This review will briefly explain the understanding of nociplastic pain, examine the evidence for the effect of cannabinoids in these conditions, and provide simplified guidance for healthcare providers who may consider prescribing cannabinoids for these conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

IASP. [cited 2021 15June2021]. https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698#Nociplasticpain. Accessed 28 Aug 2021.

Kosek E, et al. Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states? Pain. 2016;157(7):1382–6.

Fitzcharles MA, et al. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2098–110.

Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152(3 Suppl):S2-s15.

Sluka KA, Clauw DJ. Neurobiology of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. Neuroscience. 2016;338:114–29.

Devesa I, Ferrer-Montiel A. Neurotrophins, endocannabinoids and thermo-transient receptor potential: a threesome in pain signalling. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39(3):353–62.

Enck P, Mazurak N. The “Biology-First” hypothesis: functional disorders may begin and end with biology—a scoping review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(10):e13394.

Fitzcharles MA, Perrot S, Hauser W. Comorbid fibromyalgia: a qualitative review of prevalence and importance. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(9):1565–76.

Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(2):133–46.

D’Agnelli S, et al. Fibromyalgia: genetics and epigenetics insights may provide the basis for the development of diagnostic biomarkers. Mol Pain. 2019;15:1744806918819944.

Maixner W, et al. Overlapping chronic pain conditions: implications for diagnosis and classification. J Pain. 2016;17(9 Suppl):T93-t107.

Bailly F, et al. Part of pain labelled neuropathic in rheumatic disease might be rather nociplastic. RMD Open. 2020;6(2):e001326.

Pertwee RG. Endocannabinoids and Their Pharmacological Actions. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;231:1–37.

Cravatt BF, Lichtman AH. The endogenous cannabinoid system and its role in nociceptive behavior. J Neurobiol. 2004;61(1):149–60.

Anand P, et al. Targeting CB2 receptors and the endocannabinoid system for the treatment of pain. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(1):255–66.

Russo EB. Clinical endocannabinoid deficiency reconsidered: current research supports the theory in migraine, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel, and other treatment-resistant syndromes. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016;1(1):154–65.

Gould J. The cannabis crop. Nature. 2015;525(7570):S2-3.

Mehmedic Z, et al. Potency trends of Delta9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated cannabis preparations from 1993 to 2008. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55(5):1209–17.

ElSohly MA, et al. Changes in cannabis potency over the last 2 decades (1995–2014): analysis of current data in the United States. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(7):613–9.

Andre CM, Hausman JF, Guerriero G. Cannabis sativa: the plant of the thousand and one molecules. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:19.

Grof, C.P.L., Cannabis, from plant to pill. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2018.

Lucas CJ, Galettis P, Schneider J. The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(11):2468–76.

Nicholas M, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. Pain. 2019;160(1):28–37.

Arnold LM, et al. AAPT diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2019;20(6):611–28.

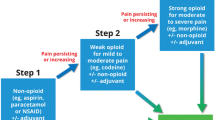

Ballantyne JC, Kalso E, Stannard C. WHO analgesic ladder: a good concept gone astray. BMJ. 2016;352:i20.

Goldenberg DL, et al. Opioid Use in Fibromyalgia: A Cautionary Tale. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(5):640–8.

Schrepf A, et al. Endogenous opioidergic dysregulation of pain in fibromyalgia: a PET and fMRI study. Pain. 2016;157(10):2217–25.

Fitzcharles MA, Shir Y, Häuser W. Medical cannabis: strengthening evidence in the face of hype and public pressure. CMAJ. 2019;191(33):E907-e908.

Martin JH, et al. Ensuring access to safe, effective, and affordable cannabis-based medicines. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86(4):630–4.

Skrabek RQ, et al. Nabilone for the Treatment of Pain in Fibromyalgia. Journal of Pain. 2008;9(2):164–73.

Ware MA, et al. The effects of nabilone on sleep in fibromyalgia: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(2):604–10.

van de Donk T, et al. An experimental randomized study on the analgesic effects of pharmaceutical-grade cannabis in chronic pain patients with fibromyalgia. Pain. 2019;160(4):860–9.

Chaves C, Bittencourt PCT, Pelegrini A. Ingestion of a THC-Rich cannabis oil in people with fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pain Med. 2020;21(10):2212–8.

Skrabek RQ, et al. Nabilone for the treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2008;9(2):164–73.

Lee JS, et al. Clinically important change in the visual analog scale after adequate pain control. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(10):1128–30.

Bennett RM, et al. Minimal clinically important difference in the fibromyalgia impact questionnaire. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(6):1304–11.

Fitzcharles MA, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of cannabinoid treatments in the rheumatic diseases: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(5):681–8.

Walitt B, et al. Cannabinoids for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(7).

Yassin M, Oron A, Robinson D. Effect of adding medical cannabis to analgesic treatment in patients with low back pain related to fibromyalgia: an observational cross-over single centre study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37(Suppl 116):S13–20.

Sagy I, et al. Safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in fibromyalgia. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):807.

Alkabbani W, et al. Persistence of use of prescribed cannabinoid medicines in Manitoba, Canada: a population‐based cohort study. Addiction. 2019;114(10):1791–99.

Boehnke KF, et al. Cannabidiol use for fibromyalgia: prevalence of use and perceptions of effectiveness in a large online survey. J Pain. 2021;22(5):556–66.

Boehnke KF et al. Substituting cannabidiol for opioids and pain medications among individuals with fibromyalgia: a large online survey. J Pain. 2021;22(11):1418-1428.

Boehnke KF, et al. Cannabidiol product dosing and decision-making in a national survey of individuals with fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2021.06.007

Robbins MS, Lipton RB. The epidemiology of primary headache disorders. Semin Neurol. 2010;30(2):107–19.

Cuttler C, et al. Short- and long-term effects of cannabis on headache and migraine. J Pain. 2020;21(5–6):722–30.

Stith SS, et al. Alleviative effects of Cannabis flower on migraine and headache. J Integr Med. 2020;18(5):416–24.

Aviram J, et al. Migraine frequency decrease following prolonged medical cannabis treatment: a cross-sectional study. Brain Sci. 2020;10(6):360.

Oka P, et al. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(10):908–17.

van Orten-Luiten AB, et al. Effects of Cannabidiol chewing gum on perceived pain and well-being of irritable bowel syndrome patients: a placebo-controlled crossover exploratory intervention study with symptom-driven dosing. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2020.0087

Desai P, et al. Association between cannabis use and healthcare utilization in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e8008.

Carrubba AR, et al. Use of cannabis for self-management of chronic pelvic pain. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;30(9):1344–51.

Wagenlehner FME, et al. Fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor treatment in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: an adaptive double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Urology. 2017;103:191–7.

Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada, Information request (ATI 2013-00282) under the Access to Information Act. 2013.

Ste-Marie PA, et al. Survey of herbal cannabis (marijuana) use in rheumatology clinic attenders with a rheumatologist confirmed diagnosis. Pain. 2016;157(12):2792–7.

Fitzcharles MA, et al. Medical cannabis use by rheumatology patients following recreational legalization: a prospective observational study of 1000 patients in Canada. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(5):286–93.

Survey, N.A.M.C. 2014 State and National Summary Tables. 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2014_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2021.

First L, et al. Cannabis Use and Low-Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2020;5(4):283–9.

Pinsger M, et al. Benefits of an add-on treatment with the synthetic cannabinomimetic nabilone on patients with chronic pain–a randomized controlled trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2006;118(11–12):327–35.

Xantus G, et al. Cannabidiol in low back pain: scientific rationale for clinical trials in low back pain. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14(6):671–5.

Takakuwa KM, et al. The impact of medical cannabis on intermittent and chronic opioid users with back pain: how cannabis diminished prescription opioid usage. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2020;5(3):263–70.

Fitzcharles M-A, et al. Position statement: a pragmatic approach for medical cannabis and patients with rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(5):532–8.

Häuser W, et al. European Pain Federation (EFIC) position paper on appropriate use of cannabis-based medicines and medical cannabis for chronic pain management. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(9):1547–64.

Fitzcharles MA, Clauw DJ, Hauser W. A cautious hope for cannabidiol (CBD) in rheumatology care. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24176.

Colizzi M, Bhattacharyya S. Does cannabis composition matter? Differential effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on human cognition. Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4(2):62–74.

Cohen K, Weinstein A. The Effects of cannabinoids on executive functions: evidence from cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids—a systematic review. Brain Sci. 2018;8(3):40.

Mensinga TT, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled, cross-over study on the pharmacokinetics and effects of cannabis. Nationaal Vergiftigingen Informatie Centrum; 2006. p. 1–52.

Ogourtsova T, et al. Cannabis use and driving-related performance in young recreational users: a within-subject randomized clinical trial. CMAJ Open. 2018;6(4):E453.

Faryar KA, Kohlbeck SA, Schreiber SJ. Shift in drug vs alcohol prevalence in milwaukee county motor vehicle decedents, 2010–2016. WMJ. 2018;117(1):24–8.

Beirness, D.J., E.E. Beasley, and P. Boase, A comparison of drug use by fatally injured drivers and drivers at risk. In: Proceedings of the the 20th International Conference on Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety T-2013; Brisbane, Australia: International Council on Alcohol, Drugs, and Traffic Safety (ICADTS). 2013.

Asbridge M, Hayden JA, Cartwright JL. Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk: systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e536.

Lee C, et al. Cohort study of medical cannabis authorization and motor vehicle crash-related healthcare visits in 2014–2017 in Ontario, Canada. Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(1):33.

Griffith-Lendering MF, et al. Cannabis use and vulnerability for psychosis in early adolescence—a TRAILS study. Addiction. 2013;108(4):733–40.

Moore TH, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):319–28.

Borges G, Bagge CL, Orozco R. A literature review and meta-analyses of cannabis use and suicidality. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:63–74.

Singh A, et al. Cardiovascular complications of marijuana and related substances: a review. Cardiol Ther. 2018;7(1):45–59.

Thomas G, Kloner RA, Rezkalla S. Adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular effects of marijuana inhalation: what cardiologists need to know. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(1):187–90.

Hackam DG. Cannabis and stroke: systematic appraisal of case reports. Stroke. 2015;46(3):852–6.

Volkow ND, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):879.

Desai R, et al. Recreational marijuana use and acute myocardial infarction: insights from nationwide inpatient sample in the United States. Cureus. 2017;9(11):e1816.

Fonseca BM, Rebelo I. Cannabis and cannabinoids in reproduction and fertility: where we stand. Reprod Sci. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-021-00588-1.

Vardaris RM, et al. Chronic administration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol to pregnant rats: studies of pup behavior and placental transfer. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1976;4(3):249–54.

Mourh J, Rowe H. Marijuana and breastfeeding: applicability of the current literature to clinical practice. Breastfeed Med. 2017;12(10):582–96.

Cooper ZD, Haney M. Actions of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in cannabis: relation to use, abuse, dependence. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(2):104–12.

van der Pol P, et al. Predicting the transition from frequent cannabis use to cannabis dependence: a three-year prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(2):352–9.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2019. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Accessed 28 August 2021.

IASP. 2021. https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=11145&navItemNumber=643.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests:

MAF, FP and WH have no financial conflicts of interest to declare. MAF is the head of a task force of the Canadian Association of Rheumatology of a position paper on medical cannabis for rheumatic diseases; core member of Health Canada Science Advisory Committee on Health Products Containing Cannabis WH is the head of EFIC’s task force of a position paper on cannabis-based medicines and medical cannabis for chronic pain and member of the task force of the German Pain Society on the same topic. FP is the head of the task force of the German Pain Society of a position paper on cannabis-based medicines and medical cannabis for chronic pain. TT has received honoraria for consultancies, travel grants and speaking fees for AOP Orphan, Almiral Hermal, Bionest Partners, Benkitt Renkiser, Grünenthal, Hexal, Indivior, Kaia Health, Lilly, Medscape, Mundipharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Recordati Pharma, Sanofi-Aventis, and TAD Pharma.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable

Code availability

Not applicable

Authors' contributions

All authors participated in writing the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fitzcharles, MA., Petzke, F., Tölle, T.R. et al. Cannabis-Based Medicines and Medical Cannabis in the Treatment of Nociplastic Pain. Drugs 81, 2103–2116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-021-01602-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-021-01602-1