Abstract

Introduction

Post-marketing safety surveillance primarily relies on data from spontaneous adverse event reports, medical literature, and observational databases. Limitations of these data sources include potential under-reporting, lack of geographic diversity, and time lag between event occurrence and discovery. There is growing interest in exploring the use of social media (‘social listening’) to supplement established approaches for pharmacovigilance. Although social listening is commonly used for commercial purposes, there are only anecdotal reports of its use in pharmacovigilance. Health information posted online by patients is often publicly available, representing an untapped source of post-marketing safety data that could supplement data from existing sources.

Objectives

The objective of this paper is to describe one methodology that could help unlock the potential of social media for safety surveillance.

Methods

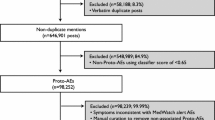

A third-party vendor acquired 24 months of publicly available Facebook and Twitter data, then processed the data by standardizing drug names and vernacular symptoms, removing duplicates and noise, masking personally identifiable information, and adding supplemental data to facilitate the review process. The resulting dataset was analyzed for safety and benefit information.

Results

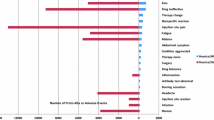

In Twitter, a total of 6,441,679 Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®) Preferred Terms (PTs) representing 702 individual PTs were discussed in the same post as a drug compared with 15,650,108 total PTs representing 946 individual PTs in Facebook. Further analysis revealed that 26 % of posts also contained benefit information.

Conclusion

Social media listening is an important tool to augment post-marketing safety surveillance. Much work remains to determine best practices for using this rapidly evolving data source.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. The importance of PV: safety monitoring of medical products. World Health Organization, United Kingdom. 2002. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s4893e/s4893e.pdf. Accessed 7 Dec 2015.

Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007. 2007. http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Legislation/SignificantAmendmentstotheFDCAct/FoodandDrugAdministrationAmendmentsActof2007/FullTextofFDAAALaw/default.htm. Accessed 16 Sept 2015.

Patadia VK, Coloma P, Schuemie MJ, Herings R, Gini R, Mazzaglia G, et al. Using real-world healthcare data for PV signal detection—the experience of the EU-ADR project. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015;8(1):95–102. doi:10.1586/17512433.2015.992878.

Trifiro G, Coloma PM, Rijnbeek PR, Romio S, Mosseveld B, Weibel D, et al. Combining multiple healthcare databases for postmarketing drug and vaccine safety surveillance: why and how? J Intern Med. 2014;275(6):551–61. doi:10.1111/joim.12159.

Stang PE, Ryan PB, Racoosin JA, Overhage JM, Hartzema AG, Reich C, et al. Advancing the science for active surveillance: rationale and design for the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(9):600–6. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-153-9-201011020-00010.

McClure DL, Raebel MA, Yih WK, Shoaibi A, Mullersman JE, Anderson-Smits C, et al. Mini-Sentinel methods: framework for assessment of positive results from signal refinement. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(1):3–8. doi:10.1002/pds.3547.

Pew Research Internet Project. Health Fact Sheet: Highlights of the Pew Internet Project’s research related to health and healthcare. http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/health-fact-sheet. Accessed 7 Aug 2015.

Nair M. Understanding and measuring the value of social media. J Corp Acc Finance. 2011;22(3):45–51.

Ghosh R, Lewis D. Aims and approaches of Web-RADR: a consortium ensuring reliable ADR reporting via mobile devices and new insights from social media. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015:1–9. doi:10.1517/14740338.2015.1096342.

Golder S, Norman G, Loke YK. Systematic review on the prevalence, frequency and comparative value of adverse events data in social media. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(4):878–88. doi:10.1111/bcp.12746.

Lardon J, Abdellaoui R, Bellet F, Asfari H, Souvignet J, Texier N, et al. Adverse drug reaction identification and extraction in social media: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(7):e171. doi:10.2196/jmir.4304.

Sloane R, Osanlou O, Lewis D, Bollegala D, Maskell S, Pirmohamed M. Social media and PV: a review of the opportunities and challenges. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(4):910–20. doi:10.1111/bcp.12717.

Sarker A, Ginn R, Nikfarjam A, O’Connor K, Smith K, Jayaraman S, et al. Utilizing social media data for PV: a review. J Biomed Inform. 2015;54:202–12. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2015.02.004.

Noren GN. PV for a revolving world: prospects of patient-generated data on the internet. Drug Saf. 2014;37(10):761–4. doi:10.1007/s40264-014-0205-4.

White RW, Harpaz R, Shah NH, DuMouchel W, Horvitz E. Toward enhanced PV using patient-generated data on the internet. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96(2):239–46. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.77.

Masoni M, Guelfi MR, Conti A, Gensini GF. PV and use of online health information. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34(7):357–8. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.05.001.

Edwards IR, Lindquist M. Social media and networks in PV: boon or bane? Drug Saf. 2011;34(4):267–71. doi:10.2165/11590720-000000000-00000.

Majumder MS, Kluberg S, Santillana M, Mekaru S, Brownstein JS. ebola outbreak: media events track changes in observed reproductive number. PLoS Curr. 2014;2015:7. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.e6659013c1d7f11bdab6a20705d1e865.

McIver DJ, Hawkins JB, Chunara R, Chatterjee AK, Bhandari A, Fitzgerald TP, et al. Characterizing sleep issues using twitter. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e140. doi:10.2196/jmir.4476.

Freifeld CC, Brownstein JS, Menone CM, Bao W, Filice R, Kass-Hout T, et al. Digital drug safety surveillance: monitoring pharmaceutical products in twitter. Drug Saf. 2014;37(5):343–50. doi:10.1007/s40264-014-0155-x.

Robinson G. A statistical approach to the spam problem. Linux J. 2003;2003(107):3.

Bloom B. Space/time trade-offs in hash coding with allowable errors. Commun ACM. 1970;13(7):422–6. doi:10.1145/362686.362692.

Hauben M, Reich L, DeMicco J, Kim K. ‘Extreme duplication’ in the US FDA adverse events reporting system database. Drug Saf. 2007;30(6):551–4.

Nikfarjam A, Sarker A, O’Connor K, Ginn R, Gonzalez G. PV from social media: mining adverse drug reaction mentions using sequence labeling with word embedding cluster features. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(3):671–81. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocu041.

Yang M, Kiang M, Shang W. Filtering big data from social media–Building an early warning system for adverse drug reactions. J Biomed Inform. 2015;54:230–40. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2015.01.011.

Sarker A, Gonzalez G. Portable automatic text classification for adverse drug reaction detection via multi-corpus training. J Biomed Inform. 2015;53:196–207. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2014.11.002.

Sarntivijai S, Abernethy DR. Use of internet search logs to evaluate potential drug adverse events. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96(2):149–50. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.115.

O’Connor K, Pimpalkhute P, Nikfarjam A, Ginn R, Smith KL, Gonzalez G. PV on twitter? Mining tweets for adverse drug reactions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014;2014:924–33.

Wu H, Fang H, Stanhope SJ. Exploiting online discussions to discover unrecognized drug side effects. Methods Inf Med. 2013;52(2):152–9. doi:10.3414/ME12-02-0004.

Abou Taam M, Rossard C, Cantaloube L, Bouscaren N, Roche G, Pochard L, et al. Analysis of patients’ narratives posted on social media websites on benfluorex’s (Mediator(R)) withdrawal in France. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39(1):53–5. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12103.

Chary M, Genes N, McKenzie A, Manini AF. Leveraging social networks for toxicovigilance. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(2):184–91. doi:10.1007/s13181-013-0299-6.

Coloma PM, Becker B, Sturkenboom MC, van Mulligen EM, Kors JA. Evaluating social media networks in medicines safety surveillance: two case studies. Drug Saf. 2015;38(10):921–30. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0333-5.

Dyar OJ, Castro-Sanchez E, Holmes AH. What makes people talk about antibiotics on social media? A retrospective analysis of Twitter use. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(9):2568–72. doi:10.1093/jac/dku165.

Harmark L, van Puijenbroek E, van Grootheest K. Intensive monitoring of duloxetine: results of a web-based intensive monitoring study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(2):209–15. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1313-7.

Pages A, Bondon-Guitton E, Montastruc JL, Bagheri H. Undesirable effects related to oral antineoplastic drugs: comparison between patients’ internet narratives and a national PV database. Drug Saf. 2014;37(8):629–37. doi:10.1007/s40264-014-0203-6.

Palosse-Cantaloube L, Lacroix I, Rousseau V, Bagheri H, Montastruc JL, Damase-Michel C. Analysis of chats on French internet forums about drugs and pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(12):1330–3. doi:10.1002/pds.3709.

Schroder S, Zollner YF, Schaefer M. Drug related problems with Antiparkinsonian agents: consumer internet reports versus published data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(10):1161–6. doi:10.1002/pds.1415.

Simmering JE, Polgreen LA, Polgreen PM. Web search query volume as a measure of pharmaceutical utilization and changes in prescribing patterns. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(6):896–903. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.01.003.

White RW, Tatonetti NP, Shah NH, Altman RB, Horvitz E. Web-scale PV: listening to signals from the crowd. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(3):404–8. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001482.

Shutler L, Nelson LS, Portelli I, Blachford C, Perrone J. Drug use in the twittersphere: a qualitative contextual analysis of tweets about prescription drugs. J Addict Dis. 2015;34(4):303–10. doi:10.1080/10550887.2015.1074505.

Lee JL, DeCamp M, Dredze M, Chisolm MS, Berger ZD. What are health-related users tweeting? A qualitative content analysis of health-related users and their messages on twitter. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(10):e237. doi:10.2196/jmir.3765.

McGregor F, Somner JE, Bourne RR, Munn-Giddings C, Shah P, Cross V. Social media use by patients with glaucoma: what can we learn? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34(1):46–52. doi:10.1111/opo.12093.

Harmark L, Puijenbroek E, Grootheest K. Longitudinal monitoring of the safety of drugs by using a web-based system: the case of pregabalin. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(6):591–7. doi:10.1002/pds.2135.

Greene JA, Choudhry NK, Kilabuk E, Shrank WH. Online social networking by patients with diabetes: a qualitative evaluation of communication with Facebook. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):287–92. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1526-3.

Cobert B, Silvey J. The Internet and drug safety: what are the implications for PV? Drug Saf. 1999;20(2):95–107.

Avillach P, Dufour JC, Diallo G, Salvo F, Joubert M, Thiessard F, et al. Design and validation of an automated method to detect known adverse drug reactions in MEDLINE: a contribution from the EU-ADR project. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(3):446–52. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001083.

Oliveira JL, Lopes P, Nunes T, Campos D, Boyer S, Ahlberg E, et al. The EU-ADR Web Platform: delivering advanced PV tools. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(5):459–67. doi:10.1002/pds.3375.

Brown D. Cool Facts About Social Media. 2012. http://dannybrown.me/2012/06/06/52-cool-facts-social-media-2012/. Accessed 16 Oct 2015.

Beevolve. An Exhaustive Study of Twitter Users Around the World. 2012. http://temp.beevolve.com/twitter-statistics/-c1. Accessed 6 Oct 2015.

Schwind JS, Wolking DJ, Brownstein JS, Consortium P, Mazet JA, Smith WA. Evaluation of local media surveillance for improved disease recognition and monitoring in global hotspot regions. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110236. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110236.

Scales D, Zelenev A, Brownstein JS. Quantifying the effect of media limitations on outbreak data in a global online web-crawling epidemic intelligence system, 2008–2011. Emerg Health Threats J. 2013;6:21621. doi:10.3402/ehtj.v6i0.21621.

Chunara R, Andrews JR, Brownstein JS. Social and news media enable estimation of epidemiological patterns early in the 2010 Haitian cholera outbreak. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(1):39–45. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0597.

Dasgupta N, Mandl KD, Brownstein JS. Breaking the news or fueling the epidemic? Temporal association between news media report volume and opioid-related mortality. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7758. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007758.

Reese S, Danielian L. Intermedia influence and the drug issue: converging on cocaine. In: Shoemaker P, editor. Communication campaigns about drugs: government, media and the public. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1989.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank many curators who have contributed to training the classifier, including Chi Bahk, Wenjie Bao, Anne Czernek, Michael Gilbert, Melissa Jordan, Christopher Menone, and Carly Winokur.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

GlaxoSmithKline paid for the research presented in this paper, including responding to reviewer comments during manuscript preparation. All work was conducted by the authors listed. Development of the social listening platform was funded in part by the US FDA under contract with Epidemico, Inc. prior to initiation and continuing throughout this research. Additional development funds for the social listening platform are provided to Epidemico, Inc. through a public–private partnership, but were not used to directly support the specific content of this research. This collaborative effort is provided via the WEB-RADR project, which is supported by the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking (IMI JU) under Grant Agreement No. 115632, resources of which are composed of financial contributions from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies’ in kind contribution. Neither the FDA, WEB-RADR, nor IMI JU had any role in this research.

Conflict of interest

Gregory Powell, Harry Seifert, Tjark Reblin, Phil Burstein, James Blowers, Alan Menius, Jeffery Painter, Michele Thomas, and Heidi Bell were employees of or contractors to GlaxoSmithKline during the study. Carrie Pierce, Harold Rodriguez, John Brownstein, Clark Freifeld, and Nabarun Dasgupta are employees of or contractors to Epidemico, Inc., a technology company intending to commercialize the software platform used in this research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Powell, G.E., Seifert, H.A., Reblin, T. et al. Social Media Listening for Routine Post-Marketing Safety Surveillance. Drug Saf 39, 443–454 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0385-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0385-6