Abstract

Background

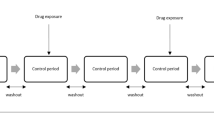

The self-controlled case series (SCCS) offers potential as an statistical method for risk identification involving medical products from large-scale observational healthcare data. However, analytic design choices remain in encoding the longitudinal health records into the SCCS framework and its risk identification performance across real-world databases is unknown.

Objectives

To evaluate the performance of SCCS and its design choices as a tool for risk identification in observational healthcare data.

Research Design

We examined the risk identification performance of SCCS across five design choices using 399 drug-health outcome pairs in five real observational databases (four administrative claims and one electronic health records). In these databases, the pairs involve 165 positive controls and 234 negative controls. We also consider several synthetic databases with known relative risks between drug-outcome pairs.

Measures

We evaluate risk identification performance through estimating the area under the receiver-operator characteristics curve (AUC) and bias and coverage probability in the synthetic examples.

Results

The SCCS achieves strong predictive performance. Twelve of the twenty health outcome-database scenarios return AUCs >0.75 across all drugs. Including all adverse events instead of just the first per patient and applying a multivariate adjustment for concomitant drug use are the most important design choices. However, the SCCS as applied here returns relative risk point-estimates biased towards the null value of 1 with low coverage probability.

Conclusions

The SCCS recently extended to apply a multivariate adjustment for concomitant drug use offers promise as a statistical tool for risk identification in large-scale observational healthcare databases. Poor estimator calibration dampens enthusiasm, but on-going work should correct this short-coming.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

United States Congress. Food and drug administration amendments act of 2007. Public Law. 2007. p. 115–85.

Woodcock J, Behrman RE, Dal Pan GJ. Role of postmarketing surveillance in contemporary medicine. Ann Rev Med. 2011;62:1–10.

Stang PE, Ryan PB, Racoosin JA, Overhage JA, Hartzema AG, Reich C, Welebob E, Scarnecchia T, Woodcock J Advancing the science for active surveillance: rationale and design for the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership. Annal Intern Med. 2010;153:600–6.

Farrington CP Relative incidence estimation from case series for vaccine safety evaluation. Biometrics. 1995;51:228–35.

Whitaker HJ, Farrington CP, Spiessens B, Musonda P. Tutorial in biostatistics: the self-controlled case series method. Stat Med. 2006;25(10):1768–97.

Grosso A, Douglas I, Hingorani A, MacAllister R, Smeeth L (2008) Post-marketing assessment of the safety of strontium ranelate; a novel case-only approach to the early detection of adverse drug reactions. British J Cli Pharmacol. 66:689–94.

Douglas I, Smeeth L (2008) Exposure to antipsychotics and risk of stroke: self controlled case series study. British Med J. 2008;337:a1227.

Nicholas JM, Grieve AP, Gulliford MC (2012) Within-person study designs had lower precision and greater susceptibility to bias because of trends in exposure than cohort and nested case-control designs. J Clin Epidemiol 65:384–93.

Taylor B, Miller E, Farrington CP, Petropoulos M-C, Favot-Mayaud I, Li J, Waight PA. Autism and measles, mumps and rubella vaccine: no epidemiological evidence for a causal association. Lancet. 1999;353:2026–9.

Hauben M, Madigan D, Gerrits C, Meyboom R. The role of data mining in pharmacovigilance. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4:929–48.

Fram D, Almenoff J, DuMouchel W. Empirical Bayesian data mining for discovering patterns in post-marketing drug safety. In: Ninth ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. 2003. p. 359–68.

Simpson SE, Madigan D, Zorych I, Schuemie MJ, Ryan PB, Suchard MA Multiple self-controlled case series for large-scale longitudinal observational databases. Biometrics (in press).

Hoerl AE, Kennard RW. Ridge regression: biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics. 1970;12:55–67.

Suchard MA, Simpson SE, Zorych I, Ryan P, Madigan D. Massive parallelization of serial inference algorithms for a complex generalized linear models. Trans Model Comput Simul 2013;23(1):10.

Ryan PB, Schuemie MJ. Evaluating performance of risk identification methods through a large-scale simulation of observational data. Drug Saf (in submission to this supplement). doi:10.1007/s40264-013-0110-2.

Ryan PB, Stang PE, Overhage JM, Suchard MA, Hartzema AG, DuMouchel W, et al. A comparison of the empirical performance of methods for a risk identification system. Drug Saf (in this supplement issue). doi:10.1007/s40264-013-0108-9.

Ryan PB, Schmuemie MJ, Welebob E, Duke J, Valentine S, Hartzema AG. Defining a reference set to support methodological research in drug safety. Drug Saf (in submission to this supplement). doi:10.1007/s40264-013-0097-8.

Armstrong B. A simple estimator of minimum detectable relative risk, sample size, or power in cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126(2):356–8.

Cantor SB, Kattan MW. Determining the area under the roc curve for a binary diagnostic test. Med Decis Mak. 2000;20(4):468–70.

Smith BM, Schwartzman K, Bartlett G, Menzies D (2011) Adverse events associated with treatment of latent tuberculosis in the general population. Can Med Assoc J 183(3):E173–9.

Bruno R, Sacchi P, Filice C, Filice G. Acute liver failure during lamivudine treatment in a hepatitis b cirrhotic patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):265.

Clark SJ, Creighton S, Portmann B, Taylor C, Wendon JA, Cramp ME (2002) Acute liver failure associated with antiretroviral treatment for hiv: a report of six cases. J Hepatol. 36(2):295–301.

Tillmann HL, Hadem J, Leifeld L, Zachou K, Canbay A, Eisenbach C, Graziadei I, Encke J, Schmidt H, Vogel W, et al. Safety and efficacy of lamivudine in patients with severe acute or fulminant hepatitis b, a multicenter experience. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13(4):256–63.

Senn S (2008) Transposed conditionals, shrinkage and direct and indirect unbiasedness. Epidemiology. 19:652–4.

Chatterjee A, Lahiri SN. Bootstrapping lasso estimators. J Am Stat Assoc. 2011;106(494):608–25.

Trifirò G, Pariente A, Coloma PM, Kors JA, Polimeni G, Miremont-Salamé G, Catania MA, Salvo F, David A, Moore N et al. Data mining on electronic health record databases for signal detection in pharmacovigilance: which events to monitor? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(12):1176–84.

Acknowledgements

The Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership was funded by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health through generous contributions from the following: Abbott, Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Bristol - Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Pfizer Inc, Pharmaceutical Research Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), Roche, Sanofi-aventis, Schering-Plough Corporation, Takeda and Biogen Idec. Dr. Ryan is a past employee of GlaxoSmithKline, but does not receive compensation for his work with OMOP. Dr. Schuemie received a fellowship from the Office of Medical Policy, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration and is presently an employee of Janssen Research and Development. Drs. Suchard and Madigan received funding from FNIH.

This article was published in a supplement sponsored by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH). The supplement was guest edited by Stephen J.W. Evans. It was peer reviewed by Olaf H. Klungel who received a small honorarium to cover out-of-pocket expenses. S.J.W.E has received travel funding from the FNIH to travel to the OMOP symposium and received a fee from FNIH for the review of a protocol for OMOP. O.H.K has received funding for the IMI-PROTECT project from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking (http://www.imi.europa.eu) under Grant Agreement no 115004, resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies’ in kind contribution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work was partially supported by National Science Foundation grant IIS 1251151. The OMOP research used data from Truven Health Analytics (formerly the Health Business of Thomson Reuters), and includes MarketScan® Research Databases, represented with MarketScan Lab Supplemental (MSLR, 1.2 m persons), MarketScan Medicare Supplemental Beneficiaries (MDCR, 4.6 m persons), MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid (MDCD, 10.8 m persons), MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCAE, 46.5 m persons). Data also provided by Quintiles® Practice Research Database (formerly General Electric’s Electronic Health Record, 11.2 m persons) database. GE is an electronic health record database while the other four databases contain administrative claims data.

Appendix

Appendix

Self-controlled case series design estimates for all test cases stratified by data source

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Suchard, M.A., Zorych, I., Simpson, S.E. et al. Empirical Performance of the Self-Controlled Case Series Design: Lessons for Developing a Risk Identification and Analysis System. Drug Saf 36 (Suppl 1), 83–93 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0100-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0100-4