Abstract

Vaccines have contributed substantially to decreasing the morbidity and mortality rates of many infectious diseases worldwide. Despite this achievement, an increasing number of parents have adopted hesitant behaviours towards vaccines, delaying or even refusing their administration to children. This has implications not only on individuals but also society in the form of outbreaks for e.g. measles, chicken pox, hepatitis A, etc. A review of the literature was conducted to identify the determinants of vaccine hesitancy (VH) as well as vaccine confidence and link them to challenges and opportunities associated with vaccination in India, safety concerns, doubts about the need for vaccines against uncommon diseases and suspicions towards new vaccines were identified as major vaccine-specific factors of VH. Lack of awareness and limited access to vaccination sites were often reported by hesitant parents. Lastly, socio-economic level, educational level and cultural specificities were contextual factors of VH in India. Controversies and rumours around some vaccines (e.g., human papillomavirus) have profoundly impacted the perception of the risks and benefits of vaccination. Challenges posed by traditions and cultural behaviours, geographical specificities, socio-demographic disparities, the healthcare system and vaccine-specific features are highlighted, and opportunities to improve confidence are identified. To overcome VH and promote vaccination, emphasis should be on improving communication, educating the new generation and creating awareness among the society. Tailoring immunisation programmes as per the needs of specific geographical areas or communities is also important to improve vaccine confidence.

Plain language summary

Similar content being viewed by others

Rumours and controversies around vaccine safety have shed light on the strong presence of parental vaccine hesitancy (VH) in India. |

A literature review identifies challenges to overcome VH as well as opportunities to improve vaccine confidence. |

Vaccine-specific causes (e.g., cost, safety concerns), individual (e.g., doubts about need to vaccinate, lack of confidence in vaccination programmes) and contextual (e.g., religion, traditions) influences are involved in parental VH. |

Healthcare workers and other health actors have a crucial role in improving confidence towards childhood vaccination by communicating accurate information about risks and benefits of vaccines to parents. |

Educating, creating awareness and tailoring immunisation programmes for each vaccine are proposed avenues to improve parental confidence in vaccination. |

Introduction

Public concerns about vaccines are as old as vaccines themselves, ranging from safety concerns to doubts about the needs for vaccination [1]. The internet has enhanced opportunities for anti-vaccine people to connect, organise and increase their share of voice at global level. As a result, the antivaccine community has succeeded in influencing individual's behaviour and lowering confidence in vaccination despite its proven effectiveness [2].

Thus, in recent years, attention has grown around the behaviour of individuals ranging from those who are total acceptors to those who are complete refusers, i.e., hesitant to take vaccines [3]. Refusing or delaying vaccination contributes to gaps in vaccine uptake and immunisation coverage—a significant factor in controlling or eliminating vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs). Thus, vaccine hesitancy (VH) is not only a threat to elimination of VPDs (e.g., measles, polio, etc.) but is also a major factor contributing to re-emergence of such diseases. There may be multiple factors stimulating VH, depending on the context, individuals and specific features of the vaccines [3, 4]. Aside from addressing these factors, improving vaccine confidence through better communication, by health authorities as well as by the scientific and pharmaceutical communities, may help to counteract VH [5,6,7]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) listed VH among the top ten threats to global health in 2019 [8]. WHO defined VH as “(…) delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and context specific, varying across time, places and vaccines. It is influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience and confidence” [3].

India, as a country, has the largest birth cohort in the world, with 27 million children born each year. It has not been able to reach the goal of 90% coverage for all vaccines included in national immunisation schedule because of various factors including VH [9, 10]. To control VPD, it is crucial to achieve high vaccination rates—this can be achieved by countering anti-vaccination messages and by increasing public confidence in vaccines [11,12,13]. It also appears key to develop campaigns that address the concerns faced by individuals hesitant to vaccinate themselves or their children [14,15,16].

The objective of this qualitative literature review was to identify (1) the set of VH determinants impacting childhood immunisation in India, (2) key challenges to overcoming reluctance to vaccination in the country and (3) major opportunities to minimise VH in India and increase confidence around vaccination.

Literature Search

First, a literature search was conducted in PubMed for research articles with “hesitancy” [All Fields] AND “India” [All Fields] over the 2015–2019 period and in Embase for additional articles published during the same period using the following search equation: (‘vaccine hesitancy India’ OR ((‘vaccine’/exp OR vaccine) AND hesitancy AND (‘India’/exp OR India))). Only articles reporting results from a quantitative or qualitative survey about VH in India were included. The search for VH determinants was complemented by narratives about recent vaccine-related controversies as well as a selection of challenges and opportunities relevant to the Indian context.

Furthermore, this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies performed by any of the authors with human participants or animals.

Determinants of VH in India

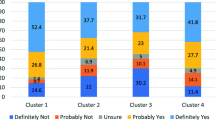

After exclusion of the articles not related to vaccination or focused on adult/traveller vaccination, nine articles reporting childhood VH determinants in India were retrieved [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Seven of them reported results from surveys or interviews of parents/caregivers in India [18,19,20,21, 23,24,25]. One study mixed a cross-sectional survey with interviews of parents and healthcare workers [17]. One article presented challenges reported by healthcare providers from different countries including India [22]. Among those nine articles, one reported results from the pulse polio campaign [18], and two were specific to measles-rubella (MR) vaccination [17, 19]. It was important to identify not only factors that add to VH in these articles but also factors that add to confidence in vaccination. Figure 1 elaborates on the findings in a form that can be shared with patients by healthcare professionals (HCPs) and Fig. 2 summarises the major factors that lower or improve vaccine confidence.

Social connections affect attitudes towards vaccination, as seen during the oral polio vaccination campaign [18]. Among the 1355 households with one or more children < 5 years old, 1074 (79.3%) accepted vaccination, while 137 were hesitant (10.1%) and 144 (10.6%) refused vaccination. Vaccine-refusing households had 189% more ties to other vaccine-refusing households than to vaccine-accepting households, which shows a clustering of VH communities.

Influence of social relationships and access to information through social media had an impact on the status of MR vaccination [19]. Vaccine acceptance was higher when offered at school (P < 0.001). It was also high among parents who trusted school teachers (P < 0.003) and other school children (P < 0.014) as sources of information. However, acceptance was lower among parents who trusted information from social media (P ≤ 0.036).

In another study, 14.1% of the 461 parents of children between 9 months and 15 years old were VH towards the MR campaign [17]. Mothers > 30 years old were found to be 2.65 times more prone to VH than younger ones (P < 0.001). Employed mothers were more prone (P < 0.001) to VH than unemployed mothers. VH was also more prevalent in parents with less education (P ≤ 0.04) than in those who had graduated. Major hindering factors were inadequate knowledge about the vaccination campaign, rumours about the safety of the vaccine, sudden planning and under-preparedness at the health system level. A major facilitating factor for the campaign was the role played by healthcare professionals in spreading awareness and increasing trust in vaccines and vaccination.

A large-scale survey (n = 20 749) was conducted to understand the dynamics of vaccine confidence in five countries, including India [25]. In the latter sub-group of households with children < 5 years old (n = 288/1 259), 36 respondents (12.5%) were found hesitant towards vaccination, among which 6 firmly refused vaccination for their children. A total of 42 reasons were provided by these 36 respondents: 13 related to confidence (safety concerns, lack of effectiveness, bad experience with vaccination or HCP or healthcare facility, preferred use of traditional medicine, religious reasons), 1 to complacency (vaccine not needed), 7 to convenience (lack of time, remoteness, vaccine shortage) and 21 to other factors (e.g., baby cries or has problems, not communicated/don’t remember). Of the 21 latter factors, “baby cries or has problem” could have been classified into “confidence”.

In another study, only 17% (33/194) of the children < 5 years old in households located in the slums of Siliguri had received vaccinations on time [23]. Reluctance to vaccinate (26.1%) and unawareness/receiving no reliable information (20.5%) were the major reasons cited for VH. Nuclear families and < 5 years schooling of the mother had higher odds of VH.

A comparison of VH across five low- and middle-income countries, including India, made using the WHO’s 10-item VH Scale, was published [21]. The VH data for India were collected between 2017 and 2018 from 309 mothers of children < 5 years old. The majority of the hesitant mothers were concerned about safety (39.2%), believed some vaccines were no longer needed (33%) or feared that newly introduced vaccines could threaten children’s health (20%). Maternal concerns about the adverse effects of vaccines, including newly introduced ones, were found at varying degrees in these five countries. No consistent association between education and VH was noted. At the same time, among all surveyed participants in Bangladesh, China, Ethiopia, Guatemala and India, a large majority perceived that vaccines are important for their child’s health (95%), that vaccines are effective (93%) and that vaccines can protect their child (94%).

In 2018, interviews at a tertiary care centre of 150 mothers of children 1 to 5 years old revealed that suspicions towards newer vaccines (61.4%), concerns about adverse events (90.7%) and perception that vaccines are not necessary for uncommon diseases (85.3%) were related to hesitant behaviour as measured by the vaccine confidence index [20, 25]. Mothers’ education was seen to protect against VH, whereas father's education, father’s use of social media and reliance on sources of information other than HCP increased the risk of VH.

A qualitative survey was conducted among 75 HCPs from four countries (UK, USA, Germany, India) in 2018 [22]. Challenges they faced were found similar (i.e., low patient-level vaccine knowledge, patient miseducation, untimely vaccine information, frequently changing schedules, pressure to achieve vaccination targets, vaccine costs). The ten Indian paediatricians interviewed reported that vaccine costs and shortages were important challenges in India. They also regret the lack of general understanding about the purpose of vaccines in segments of the population.

A questionnaire based on that created by the WHO strategic advisory group of experts on immunisation was also administered to 260 households (Balangir: 180; Nuapada: 80) in Odisha [24]. Nearly 85% had monthly incomes < 5000 Indian rupees (75 US dollars). Almost all knew that vaccines protect against infectious diseases and that parents should vaccinate their children. Around 10% highlighted long travel distances as important barriers to vaccine uptake. Nearly 28% and 9% of parents in Balangir and Nuapada, respectively, had heard negative information about the vaccines. Still, > 75% of them had their children vaccinated.

Challenges Surrounding Vaccine Hesitancy or Confidence in India

Many challenges surround vaccination in India and need to be addressed. However, some are particularly prominent because of their impact or shared roots with broader health issues.

Rumours and Controversies

Several controversies and false information have negatively impacted vaccine confidence over the last 20 years. During poliomyelitis vaccination programmes in early 2000, a seed of distrust was sown in particular communities by linking vaccination with sterility and by falsely claiming that pig’s blood was present in the vaccine, among other things [26, 27]. However, realising the importance of vaccination, religious leaders who were silent initially, along with community influencers, eventually actively fostered the social mobilisation that led to the successful elimination of poliomyelitis [28, 29].

Safety concerns of a severe nature were raised after the deaths of seven girls during two human papillomavirus (HPV) studies conducted in 2010 [30, 31]. An enquiry committee investigated the controversial cases and concluded that the vaccines were not responsible for the deaths [32]. Vaccination against HPV has the potential to provide great benefits for the Indian population as cervical cancer, which is mainly caused by persistent HPV infection, is the second most common cancer in Indian women [33]. Nevertheless, the call for introduction of HPV vaccine is still opposed despite recommendation by the Indian Council of Medical Research and the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation [34].

The decision to introduce Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) containing pentavalent vaccines in the universal immunisation programme in 2009 is yet another example of challenges regarding the need and risk-benefit ratio of vaccines. In this case, questions were raised based on studies suggesting lower burden of Hib meningitis in Indian children than in other parts of the world and based on the suggestion—that use of the pentavalent vaccines had low value to children’s health [35]. Based on available evidence, concerns were found to be unsubstantiated and the government eventually introduced the pentavalent vaccines in 2011 [35, 36].

Social Interactions

Behaviour with respect to vaccination tends to depend on who you know, where you live or both. For example, low uptake of the MR vaccine (44% of the targeted number of children) during the 2017 vaccination campaign in Tamil Nadu [19] reflects the hesitant behaviour of parents associated with safety concerns that are usually spread through social interaction and media.

Healthcare System and Access to Facilities

India has various geographical features with areas that are either densely or sparsely populated. In 2012, only 37% (versus 73%) and 68% (versus 92%) of people living in rural (versus urban) areas were able to access inpatient hospitalisation and outpatient facilities, respectively [37]. Results from pooled, nationally representative surveys covering 1998–2008 evidenced that lack of access to immunisation facilities, along with absence of healthcare workers, and ignorance of the place and timing for getting vaccination were among the reasons for delayed or missed vaccination [38]. Strong reductions of urban versus rural disparities in full vaccination rates from 2008 to 2013 are however noteworthy [39]. This is possibly due to the activation of primary health centres, subcentres and community health workers (Anganwadi workers) in rural areas [40]. Contrarily, precarious populations living in urban slums have been found to lack awareness about immunisation benefits and experience difficulties in accessing healthcare services [41, 42]. Lack of access to healthcare facilities and awareness are reasons for the low vaccination rates observed in the poorest strata of the Indian population [40, 42]. Lack of adequate workforce observed in both public and private sectors negatively impacts the healthcare standards and thereby the general trust of the population in the healthcare system [43]. Inadequate workforce increases the pressure on healthcare workers and may lower their availability for discussing parent’s concerns regarding vaccination. Previous negative experience with HCPs was indeed reported as one of the reasons for VH [25], and healthcare workers’ lack of empathy in slums (possibly due to elevated workloads) was perceived as a barrier in the immunisation process [44].

Economic Factors

The community-based cross-sectional study conducted in Mumbai, one of the world's most populous cities, identified the loss of daily income as one of the most frequently reported factors for missing childhood immunisation in slum areas [44]. The cost of vaccines and vaccination is a challenge, as very few are offered free or as part of the national immunisation programme [22]. Nevertheless, VH is also observed in populations with higher socio-economic statuses and education levels [45].

Vaccine-Specific Challenges

Vaccination schedules are designed in a way that several vaccines are administered concomitantly to improve compliance and coverage. However, due to overcrowding of vaccination schedules, HCPs and parents have concerns to administer several vaccines during a single visit [46]. Additionally, suspicions towards newly introduced vaccines, as well as doubts about the need to vaccinate against diseases that are uncommon, are recurrently reported in the Indian population [20, 21, 23].

Opportunities to Increase Vaccine Confidence in India

Some of the above-mentioned challenges come with opportunities to address VH and increase confidence in vaccination and the health system. Moreover, identification of determinants of VH allows tailoring of immunisation programmes, campaigns and policies. Tailoring immunisation programmes has proven efficient to address gaps in vaccine uptake among population, notably by addressing VH [47,48,49]. Here, we present some leads that we believe are worthy to address VH in India.

Communication

Media can have a tremendous influence on public opinion, with long-lasting impacts [50]. Today, access to social media (72.9% of households use smartphones) is far greater in India than access to TV (45.0%) or cooking gas cylinders (21.6%) [18]. Usually, mothers seek information online, especially when concerned about vaccine safety [51]. As it is difficult to control and verify all the information available on the various platforms, it is important to increase access to transparent and scientifically validated information about the risks and benefits of vaccines as well as answer questions with balanced and accurate information.

There is a global realisation that public health communicators need to adapt their communication in a way to improve trust in vaccines and vaccination [51,52,53]. Some proposed strategies go even one step further, suggesting to focus vaccine communication on the positive, emotional values of immunisations rather than limiting it to the scientific content [5, 6].

Healthcare workers remain the most trusted advisors among all possible sources of reliable information when it comes to vaccination [54, 55]. In that regard, and in light of the factors of VH reported in the literature search, availability and preparedness of healthcare workers for discussing vaccination are of prime importance. Some paediatricians are already engaged in improving vaccine confidence through the publication of scientifically accurate blogs with the potential to reach a broad audience [56]. The situation in low- and middle-income countries is even more closely impacted by the healthcare workers (i.e., including community health workers, Anganwadi workers, auxiliary nurse midwifes and health assistants), as they represent the frontline of vaccination and are often confronted with questions from hesitant parents [57,58,59]. Therefore, communication training of healthcare workers appears to be one of the most promising strategies to deal with VH and improve vaccine confidence [59]. For example, applying the CASE (Corroborate, About Me, Science, and Explain/Advise) approach could help them establish a dialogue with parents [60]. This approach could even reinforce the impact of self-help groups that are already shown to improve healthcare access and awareness in rural communities [61].

Similarly, religious leaders should also be included as important partners when communicating about immunisation as they can have a major impact when supporting it [62]. For example, the mobilisation of Muslim leaders in India was instrumental in the eradication of poliomyelitis [28].

These opportunities around communication might help overcome some of the above-mentioned challenges posed by the cultural context of India as well as by the behaviour of healthcare workers and parent’s due to safety concerns.

Education and Creating Awareness

Educating and creating awareness about immunisation and fostering critical thinking on associated risks and benefits could have a tremendous impact on overcoming hesitant behaviour in a population [63]. Such an approach has proven advantageous in a different context, i.e., reduced use of polluting firecrackers during the Diwali festival [64, 65]. Including a basic curriculum on VPDs in schools could also have a positive impact in the long term by making the new generation aware of vaccination's risks and benefits (e.g., HPV) [66, 67]. Moreover, school teachers are recognised as a trustworthy source of information by parents accepting vaccination [19]. Schools and school teachers should therefore be engaged in vaccination campaigns as they embody knowledge to the population and also have the potential to dissipate cultural barriers, which are a deterrent to vaccination.

Addressing Safety Concerns

Aside from their potential to mitigate parents’ safety concerns about multiple vaccine injections during a single visit, combination vaccines have economic value by reducing the number of injections and inherent administration and stocking costs [68, 69]. In India, the current schedule includes the pentavalent combination vaccine against diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DTP), hepatitis B (HepB), Hib and a separate polio vaccination, with either the live attenuated oral vaccine (OPV) or the inactivated injected vaccine (IPV) [70]. The use of an available hexavalent vaccine against these six diseases (DTP-HepB-Hib-IPV) could alleviate the barriers posed by parents’ fear of pain and adverse effects of vaccination. This would also foster the switch from OPV to IPV as the risk of a vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreak exists when using OPV [71, 72]. As already mentioned, the benefit of these recommendations should be transparently communicated from a public health and an economic perspectives. Assessments of the value and risk of the vaccines are important aspects for the perception of any vaccine. Therefore, nurturing and using the national surveillance programme of adverse events following immunisation is of prime importance for building evidence about vaccine safety and assuring the public that continuous monitoring is in place to help assessing any suspicion of safety issue [73].

Summary

Immunisation has been one of the key interventions that has not only reduced morbidity or mortality of some diseases [10], but also has led to eradication of small pox and now puts polio on the verge of eradication [72, 74]. Despite these achievements, there are growing concerns with respect to vaccination acceptance among the general population, which is largely driven by lack of vaccine confidence or VH.

VH has notably been attributed to factors such as safety [17, 19,20,21, 23,24,25]; rumours and controversies (e.g., vaccination leads to infertility) [17, 26, 27]; lack of awareness about benefits of vaccines [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]; influence of stakeholders (e.g., local leaders) in shaping perceptions among the general population [19, 24, 26]; costs [22]; temporal and geographic barriers [23,24,25]; and personal attributes [17, 19, 20, 23, 25].

To address the problem of VH in India, there is a need to estimate its root causes, formulate context-specific strategies relevant to the local settings and thus help in restoring trust leading to increased confidence in vaccination. The literature revealed a diversity of settings, sometimes revealing conflicting results about the analysed factors of VH (e.g., the level of education), further highlighting the context-specific nature of VH in India. The proposed strategies include the involvement of local stakeholders; encouraging the use of different mass media techniques to increase awareness of risks and benefits and address the prevalent myths about vaccines and vaccination; improving convenience and accessibility to the vaccines; employing reminder and follow-up services; organising training sessions for healthcare workers to enhance their communication skills and ability to engage in balanced and scientifically validated dialogues with parents; providing nonfinancial incentives to immunised individuals. The success of the polio campaign that helped in its elimination in India can be attributed to all the above factors and could serve as an example for overcoming challenges in vaccination.

The issue of VH in India is vast, complex and could not be exhaustively covered in one paper. The literature search focused on VH regarding childhood vaccination resulted in the retrieval of few studies specific to it. However, we are confident that they provide useful insight into the contemporaneous concerns surrounding vaccines and vaccination in the Indian population. Also, the present literature review focused on identifying the major drivers of VH and ways to leverage these for increasing vaccine confidence.

As illustrated by the paucity of published data about VH or Confidence determinants in India and the recognised challenges surrounding vaccination, further research is needed. A first important step would be the identification of VH as well as vaccine confidence its measure across India. Survey tools could help to conduct qualitative or quantitative studies in areas of low vaccine uptake and implement strategies to increase vaccine confidence. Nevertheless, the present study provides a picture of the breadth of knowledge about VH determinants in India, identifies challenges and opportunities to improve confidence. The collective use of the identified opportunities seems key to help turn vaccines into vaccination in India.

Change history

18 June 2020

In the original publication, the fourth author name was incorrectly published as Jayant Ray.

References

Larson HJ, Cooper LZ, Eskola J, Katz SL, Ratzan S. Addressing the vaccine confidence gap. Lancet. 2011;378(9790):526–35.

Black S, Rappuoli R. A crisis of public confidence in vaccines. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(61):61mr1.

World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. 2014. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 28 May 2019.

Kumar D, Chandra R, Mathur M, Samdariya S, Kapoor N. Vaccine hesitancy: understanding better to address better. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5(1):2.

Gesualdo F, Zamperini N, Tozzi AE. To talk better about vaccines, we should talk less about vaccines. Vaccine. 2018;36(34):5107–8.

Goldstein S, MacDonald NE, Guirguis S. Health communication and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4212–4.

Nowak GJ, Gellin BG, MacDonald NE, Butler R. Addressing vaccine hesitancy: the potential value of commercial and social marketing principles and practices. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4204–11.

World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019. Accessed 28 May 2019.

VanderEnde K, Gacic-Dobo M, Diallo MS, Conklin LM, Wallace AS. Global routine vaccination coverage—2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(45):1261–4.

World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011–2020. https://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/. Accessed 05 Nov 2019.

Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, et al. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4165–75.

Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Taylor JA, et al. Development of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(4):419–25.

Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, et al. Validity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine. 2011;29(38):6598–605.

Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–203.

Eskola J, Duclos P, Schuster M, MacDonald NE. How to deal with vaccine hesitancy? Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4215–7.

Jarrett C, Wilson R, O’Leary M, Eckersberger E, Larson HJ. Strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy—a systematic review. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4180–90.

Krishnamoorthy Y, Kannusamy S, Sarveswaran G, Majella MG, Sarkar S, Narayanan V. Factors related to vaccine hesitancy during the implementation of Measles-Rubella campaign 2017 in rural Puducherry—a mixed-method study. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8(12):3962–70.

Onnela J-P, Landon BE, Kahn A-L, et al. Polio vaccine hesitancy in the networks and neighborhoods of Malegaon. India Soc Sci Med. 2016;153:99–106.

Palanisamy B, Gopichandran V, Kosalram K. Social capital, trust in health information, and acceptance of Measles-Rubella vaccination campaign in Tamil Nadu: a case–control study. J Postgrad Med. 2018;64(4):212–9.

Sankaranarayanan S, Jayaraman A, Gopichandran V. Assessment of vaccine hesitancy among parents of children between 1 and 5 years of age at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Chennai. Indian J Community Med Off Publ Indian Assoc Prev Soc Med. 2019;44(4):394–6.

Wagner AL, Masters NB, Domek GJ, et al. Comparisons of vaccine hesitancy across five low- and middle-income countries. Vaccines (Basel). 2019;7(4):155.

Wiot F, Shirley J, Prugnola A, Di Pasquale A, Philip R. Challenges facing vaccinators in the 21st century: results from a focus group qualitative study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(12):2806–15.

Dasgupta P, Bhattacherjee S, Mukherjee A, Dasgupta S. Vaccine hesitancy for childhood vaccinations in slum areas of Siliguri, India. Indian J Public Health. 2018;62(4):253–8.

Sharma S, Akhtar F, Singh RK, Mehra S. Understanding the three As (Awareness, Access, and Acceptability) dimensions of vaccine hesitancy in Odisha, India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;8(2):399–403.

Larson HJ, Schulz WS, Tucker JD, Smith DMD. Measuring vaccine confidence: introducing a global vaccine confidence index. PLoS Curr. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.outbreaks.ce0f6177bc97332602a8e3fe7d7f7cc4.

Chaturvedi S, Dasgupta R, Adhish V, et al. Deconstructing social resistance to pulse polio campaign in two North Indian districts. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46(11):963–74.

Hussain RS, McGarvey ST, Fruzzetti LM. Partition and poliomyelitis: an investigation of the polio disparity affecting muslims during India's eradication program. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0115628.

Merten M. India Pakistan, and polio. BMJ. 2016;353:i2417.

Siddique AR, Singh P, Trivedi G. Role of social mobilization (Network) in polio eradication in India. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53(Suppl 1):S50–S56.

Choudhury P, John TJ. Human papilloma virus vaccines and current controversy. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47(8):724–5.

Kaarthigeyan K. Cervical cancer in India and HPV vaccination. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2012;33(1):7–12.

Final Report of the Committee appointed by the Govt. of India to enquire into “Alleged irregularities in the conduct of studies using Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine” by PATH in India February 15, 2011. https://164.100.60.236/final/HPV%20PATH%20final%20report.pdf. Accessed 06 June 2019.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer today. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. Accessed 10 Mar 2020.

Das M. Cervical cancer vaccine controversy in India. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(2):e84.

Nair H, Hazarika I, Patwari A. A roller-coaster ride: Introduction of pentavalent vaccine in India. J Glob Health. 2011;1(1):32–5.

Bairwa M, Pilania M, Rajput M, et al. Pentavalent vaccine: a major breakthrough in India's Universal Immunization Program. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(9):1314–6.

IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Understanding Healthcare Access in India. 2013. https://docshare04.docshare.tips/files/25555/255552955.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

Francis MR, Nohynek H, Larson H, et al. Factors associated with routine childhood vaccine uptake and reasons for non-vaccination in India: 1998–2008. Vaccine. 2018;36(44):6559–66.

Shenton LM, Wagner AL, Bettampadi D, Masters NB, Carlson BF, Boulton ML. Factors associated with vaccination status of children aged 12–48 months in India, 2012–2013. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(3):419–28.

Shrivastwa N, Gillespie BW, Kolenic GE, Lepkowski JM, Boulton ML. Predictors of vaccination in india for children aged 12–36 months. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6):S435–S444.

Crocker-Buque T, Mindra G, Duncan R, Mounier-Jack S. Immunization, urbanization and slums—a systematic review of factors and interventions. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):556.

Devasenapathy N, Ghosh Jerath S, Sharma S, Allen E, Shankar AH, Zodpey S. Determinants of childhood immunisation coverage in urban poor settlements of Delhi, India: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e013015.

Kasthuri A. Challenges to healthcare in India—the Five A's. Indian J Community Med Off Publ Indian Assoc Prev Soc Med. 2018;43(3):141–3.

Singh S, Sahu D, Agrawal A, Vashi MD. Barriers and opportunities for improving childhood immunization coverage in slums: a qualitative study. Prev Med Rep. 2019;14:100858.

Narayanan S, Jayaraman A, Gopichandran V. Vaccine hesitancy and attitude towards vaccination among parents of children between 1–5 years of age attending a tertiary care hospital in Chennai. India Indian J Community Fam Med. 2018;4(2):31–6.

Wallace AS, Mantel C, Mayers G, Mansoor O, Gindler JS, Hyde TB. Experiences with provider and parental attitudes and practices regarding the administration of multiple injections during infant vaccination visits: lessons for vaccine introduction. Vaccine. 2014;32(41):5301–10.

World Health Organization. The Guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). 2013. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/187347/The-Guide-to-Tailoring-Immunization-Programmes-TIP.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2019.

Butler R, MacDonald NE. Diagnosing the determinants of vaccine hesitancy in specific subgroups: the Guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4176–9.

Van Damme P, Lindstrand A, Kulane A, Kunchev A. Commentary to: Guide to tailoring immunization programmes in the WHO European Region. Vaccine. 2015;33(36):4385–6.

Getman R, Helmi M, Roberts H, Yansane A, Cutler D, Seymour B. Vaccine hesitancy and online information: the influence of digital networks. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(4):599–606.

Vrdelja M, Kraigher A, Verčič D, Kropivnik S. The growing vaccine hesitancy: exploring the influence of the internet. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28(5):934–9.

Betsch C, Brewer NT, Brocard P, et al. Opportunities and challenges of Web 2.0 for vaccination decisions. Vaccine. 2012;30(25):3727–33.

Stahl JP, Cohen R, Denis F, et al. The impact of the web and social networks on vaccination. New challenges and opportunities offered to fight against vaccine hesitancy. Med Mal Infect. 2016;46(3):117–22.

Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34(52):6700–6.

Thomson A, Vallée-Tourangeau G, Suggs LS. Strategies to increase vaccine acceptance and uptake: from behavioral insights to context-specific, culturally-appropriate, evidence-based communications and interventions. Vaccine. 2018;36(44):6457–8.

Bryan MA, Gunningham H, Moreno MA. Content and accuracy of vaccine information on pediatrician blogs. Vaccine. 2018;36(5):765–70.

Sridhar S, Maleq N, Guillermet E, Colombini A, Gessner BD. A systematic literature review of missed opportunities for immunization in low- and middle-income countries. Vaccine. 2014;32(51):6870–9.

Kestenbaum LA, Feemster KA. Identifying and addressing vaccine hesitancy. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44(4):e71–e75.

Patel AR, Nowalk MP. Expanding immunization coverage in rural India: a review of evidence for the role of community health workers. Vaccine. 2010;28(3):604–13.

Jacobson RM, St. Sauver JL, Finney Rutten LJ. Vaccine hesitancy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(11):1562–8.

Saha S, Annear PL, Pathak S. The effect of Self-Help Groups on access to maternal health services: evidence from rural India. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):36.

Tomkins A, Duff J, Fitzgibbon A, et al. Controversies in faith and health care. Lancet. 2015;386(10005):1776–85.

Arede M, Bravo-Araya M, Bouchard É, et al. Combating vaccine hesitancy: teaching the next generation to navigate through the post truth era. Front Public Health. 2019;6:381.

Ghei D, Sane R. Estimates of air pollution in Delhi from the burning of firecrackers during the festival of Diwali. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0200371.

Government of National Capital Territory Dehli - Directorate of Education. Circular: Anti Fire Crackers Campaign. 2017. https://www.edudel.nic.in/upload/upload_2017_18/2157_dt_27092017a.pdf. Accessed 04 Sept 2019.

Maisonneuve AR, Witteman HO, Brehaut J, Dubé È, Wilson K. Educating children and adolescents about vaccines: a review of current literature. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(4):311–21.

Lefevre H, Samain S, Ibrahim N, et al. HPV vaccination and sexual health in France: empowering girls to decide. Vaccine. 2019;37(13):1792–8.

Ciarametaro M, Bradshaw SE, Guiglotto J, Hahn B, Meier G. Hidden efficiencies: making completion of the pediatric vaccine schedule more efficient for physicians. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(4):e357.

Koslap-Petraco MB, Judelsohn RG. Societal impact of combination vaccines: experiences of physicians, nurses, and parents. J Pediatr Health Care. 2008;22(5):300–9.

National Health Portal—India. Universal Immunisation Programme. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/universal-immunisation-programme_pg. Accessed 05 Nov 2019.

Bahl S, Hasman A, Eltayeb AO, James Noble D, Thapa A. The switch from trivalent to bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine in the South-East Asia Region. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(suppl_1):S94–S100.

Patel M, Zipursky S, Orenstein W, Garon J, Zaffran M. Polio endgame: the global introduction of inactivated polio vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14(5):749–62.

Joshi J, Das MK, Polpakara D, Aneja S, Agarwal M, Arora NK. Vaccine safety and surveillance for adverse events following immunization (AEFI) in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85(2):139–48.

Thompson KM, Duintjer Tebbens RJ. Lessons from the polio endgame: overcoming the failure to vaccinate and the role of subpopulations in maintaining transmission. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(suppl_1):S176–S182.

Acknowledgements

Funding

GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA funded this review and all costs associated with its development and publication. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

The authors thank Business & Decision Life Science platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination on behalf of GSK. Benjamin Lemaire coordinated publication development and editorial support. Jonathan Ghesquiere provided medical writing support. Editorial support and medical writing assistance were funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. The authors also thank the reviewers who have helped improve the quality of the present review manuscript.

Disclosures

Ashish Agrawal is an employee of the GSK group of companies and declare no non-financial conflicts of interest. Alberta Di Pasquale and Shafi Kolhapure are employees of the GSK group of companies, hold shares as part of their employee remuneration and declare no non-financial conflicts of interest. Jayant Rai, who was an employee of the GSK group of companies during the conduct of the study, is currently employed by the Department of Pharmacology, Government Institute of Medical Sciences, Greater Noida, India, and declares no non-financial conflicts of interest. Ashish Mathur declares no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies performed by any of the authors with human participants or animals.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised, fourth author name was incorrectly published as Jayant Ray. The correct name should read as “Jayant Rai”.

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12220523.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Agrawal, A., Kolhapure, S., Di Pasquale, A. et al. Vaccine Hesitancy as a Challenge or Vaccine Confidence as an Opportunity for Childhood Immunisation in India. Infect Dis Ther 9, 421–432 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00302-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00302-9