Abstract

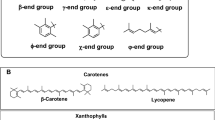

Synthetic astaxanthin (S-AX) was tested against natural astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis microalgae (N-AX) for antioxidant activity. In vitro studies conducted at Creighton University and Brunswick Laboratories showed N-AX to be over 50 times stronger than S-AX in singlet oxygen quenching and approximately 20 times stronger in free radical elimination. N-AX has been widely used over the last 15 years as a human nutraceutical supplement after extensive safety data and several health benefits were established. S-AX, which is synthesised from petrochemicals, has been used as a feed ingredient, primarily to pigment the flesh of salmonids. S-AX has never been demonstrated to be safe for use as a human nutraceutical supplement and has not been tested for health benefits in humans. Due to safety concerns with the use of synthetic forms of other carotenoids such as canthaxanthin and beta-carotene in humans, the authors recommend against the use of S-AX as a human nutraceutical supplement until extensive, long-term safety parameters have been established and human clinical trials have been conducted showing potential health benefits. Additionally, differences in various other properties between SAX and N-AX such as stereochemistry, esterification and the presence of supporting naturally occurring carotenoids in N-AX are discussed, all of which elicit further questions as to the safety and potential health benefits of S-AX. Ultimately, should S-AX prove safe for direct human consumption, dosage levels roughly 20–30 times greater than N-AX should be used as a result of the extreme difference in antioxidant activity between the two forms.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Capelli B, Cysewski G (2012) The world’s best kept health secret: natural astaxanthin. Cyanotech Corporation, Kailua-Kona, HI

Shiratori K, Ogami K, Nitta T (2005) The effects of astaxanthin on accommodation and asthenopia: efficacy identification study in healthy volunteers. J Clin Med 21(6):637–650

Satoh A, Tsuji S, Okada Y, Murakami N, Urami M, Nakagawa K, Ishikura M, Katagiri M, Koga Y, Shirasawa T (2009) Preliminary clinical evaluation of toxicity and efficacy of a new astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract. J Clin Biochem Nutr 44(3):280–284

Nakagawa K, Kiko T, Miyazawa T, Carpentero Burdeos G, Kimura F, Satoh A (2011) Antioxidant effect of astaxanthin on phospholipid peroxidation in human erythrocytes. Br J Nutr 105(11):1563–1571

Savouré N, Briand G, Amory-Touz M, Combre A, Maudet M (1995) Vitamin A status and metabolism of cutaneous polyamines in the hairless mouse after UV irradiation: action of beta-carotene and astaxanthin. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 65(2):79–86

Yamashita E (2006) The effects of a dietary supplement containing astaxanthin on skin condition. Carotenoid Sci (10):91–95

Lee S, Bai S, Lee K, Namkoong S, Na H, Ha K, Han J, Yim S, Chang K, Kwon Y, Lee S, Kim Y (2003) Astaxanthin inhibits nitric oxide production and inflammatory gene expression by suppressing IkB kinase-dependent NFR-kB activation. Mol Cells 16(1):97–105

Ohgami K, Shiratori K, Kotake S, Nishida T, Mizuki N, Yazawa K, Ohno S (2003) Effects of astaxanthin on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 44(6):2694–2701

Park JS, Chyun JH, Kim YK, Line LL, Chew BP (2010) Astaxanthin decreased oxidative stress and inflammation and enhanced immune response in humans. Nutr Metab (Lond) 7:18

Yoshida H, Yanai H, Ito K, Tomono Y, Koikeda T, Tsukahara H, Tada N (2010) Administration of natural astaxanthin increases serum HDL-cholesterol and adiponectin in subjects with mild hyperlipidemia. Atherosclerosis 209:520–523

Bagchi D, Das DK, Engelman RM, Prasad MR, Subramanian R (1990) Polymorphonuclear leucocytes as potential source of free radicals in the ischaemic-reperfused myocardium. Eur Heart J 11(9):800–813

Bagchi M., Hassoun EA, Bagchi D, Stohs SJ (1993) Production of reactive oxygen species by peritoneal macrophages and hepatic mitochondria and microsomes from endrintreated rats. Free Radic Biol Med 14:149

Sen CK, Khanna S, Roy S (2006) Tocotrienols: vitamin E beyond tocopherols. Life Sci 78(18):2088–2098

Helzlsouer K, Huang H-Y, Alberg A, Hoffman S, Burke A, Norkus E, Morris J, Comstock G (2000) Association between α-tocopherol, α-tocopherol, selenium, and subsequent prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 92(24):2018–2023

Moorhead K, Capelli B, Cysewski G (2005) Nature’s superfood: spirulina. Cyanotech Corporation, Kailua-Kona, HI, USA. ISBN #0-9637511-3-1

Ben-Amotz A, Mokady S, Edelstein A, Avron M (1989) Bioavailability of a natural isomer mixture as compared with synthetic all-trans-beta-carotene in rats and chicks. J Nutr 119(7):1013

Ben-Amotz A, Levy Y (1996) Bioavailability of a natural isomer mixture compared with synthetic all-trans betacarotene in human serum. Am J Clin Nutr 63(5):729–734

Heinonen OP, Albanes D (1994) The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N Engl J Med 330:1029–1035

Xue KX, Wu JZ, Ma GJ, Yuan S, Qin HL (1998) Comparative studies on genotoxicity and antigenotoxicity of natural and synthetic beta-carotene stereoisomers. Mutat Res 418(2–3):73–78

European Commission Health & Consumer Protection Directorate-General (2002) Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Animal Nutrition on the use of canthaxanthin in feeding stuffs for salmon and trout, laying hens, and other poultry. European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scan/out81_en.pdf. Accessed 20 December 2012

Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (2011) Standard 1.2.4: Labelling of ingredients. http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2011C00827. Australian Government. Accessed 27 October 2011

Hueber A, Rosentreter A, Severin M (2011) Canthaxanthin retinopathy: long-term observations. Ophthalmic Res 46(2):103–106

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capelli, B., Bagchi, D. & Cysewski, G.R. Synthetic astaxanthin is significantly inferior to algal-based astaxanthin as an antioxidant and may not be suitable as a human nutraceutical supplement. Nutrafoods 12, 145–152 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13749-013-0051-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13749-013-0051-5