Abstract

Purpose of Review

The progressive nature of dementia requires ongoing care delivered by multidisciplinary teams, including rehabilitation professionals, that is individualized to patient and caregiver needs at various points on the disease trajectory. Video telehealth is a rapidly expanding model of care with the potential to expand dementia best practices by increasing the reach of dementia providers to flexible locations, including patients’ homes. We review recent evidence for in-home video telehealth for patients with dementia and their caregivers with emphasis on implications for rehabilitation professionals.

Recent Findings

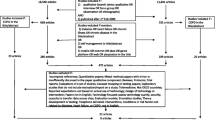

Eleven studies were identified that involved video visits into the home targeting patients with dementia and/or their family caregivers. The majority describe protocolized interventions targeting caregivers in a group format over a finite, pre-determined period. For most, the discipline of the interventionist was unclear, though two studies included rehabilitation interventions. While descriptions of utilized technology were often lacking, many reported that devices were issued to participants when needed and that technical support was provided by study teams. Positive caregiver outcomes were noted but evidence for patient-level outcomes and cost data are mostly lacking.

Summary

More research is needed to demonstrate implementation of dementia best care practices through in-home video telehealth. Though interventions delivered using in-home video telehealth appear to be effective in addressing caregivers’ psychosocial concerns, the impact on patients and the implications for rehabilitation remain unclear. Larger, more systematic inquiries comparing in-home video telehealth to traditional visit formats are needed to better define best practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. 2018, Alzheimer's Association: Chicago.

•• Cations M, et al. Rehabilitation in dementia care. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):171–4 Provides support for the inclusion of rehabilitation in dementia care, describing the importance of multidisciplinary teams in chronic disease management. Authors note the continued absence of rehabilitation professionals in dementia evidence and practice.

Hopper TL. “They’re just going to get worse anyway”: perspectives on rehabilitation for nursing home residents with dementia. J Commun Disord. 2003;36(5):345–59.

Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, Stewart D, Rigby P, Letts L. The person-environment-occupation model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Can J Occup Ther. 1996;63(1):9–23.

Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):729–36.

•• Jennings LA, Turner M, Keebler C, Burton CH, Romero T, Wenger NS, et al. The effect of a comprehensive dementia care management program on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(3):443–8 Presents a dementia care co-management framework in which nurse practitioners work with primary care providers and community organizations to deliver coordinated, comprehensive dementia care, incorporating advance care planning.

Callahan CM, Sachs GA, LaMantia MA, Unroe KT, Arling G, Boustani MA. Redesigning systems of care for older adults with Alzheimer's disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):626–32.

•• Bott NT, et al. Systems delivery innovation for alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(2):149–61 Bott et al present a comprehensive care model for dementia that demonstrates value within 1–3 years after implementation, through focused outpatient chronic disease management, acute care that is cognitively protective, and targeted caregiver support.

•• Koumakis L, et al. Dementia care frameworks and assistive technologies for their implementation: a review. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2019;12:4–18 Reviews scope of assistive technologies for dementia with a focus on caregivers as end users through the lens of an integrated care model. Presents trends and recent technological advances and identifies gaps in extant research.

Yang M, Thomas J, Zimmer R, Cleveland M, Hayashi JL, Colburn JL. Ten things every geriatrician should know about house calls. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(1):139–44.

•• Jutkowitz E, Scerpella D, Pizzi LT, Marx K, Samus Q, Piersol CV, et al. Dementia family caregivers' willingness to pay for an in-home program to reduce behavioral symptoms and caregiver stress. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019. Examines caregivers of persons with dementia’s willingness to pay for an him-home behavioral management program, finding that caregivers who are providing the most hands-on assistance are more willing to pay for in-home assistance;37:563–72.

Clare L. Rehabilitation for people living with dementia: a practical framework of positive support. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002245.

Lee WC, Dooley KE, Ory MG, Sumaya CV. Meeting the geriatric workforce shortage for long-term care: opinions from the field. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2013;34(4):354–71.

• Shigekawa E, Fix M, Corbett G, Roby DH, Coffman J. The current state of telehealth evidence: a rapid review. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(12):1975–82 Reviews twenty systematic review and meta-analyses of telehealth involving disciplines that include rehabilitation, finding approximate equivalence between in-person and telehealth but highlighting considerations such as quality of evidence.

Glueckauf RL, Loomis JS. Alzheimer’s Caregiver Support Online: lessons learned, initial findings and future directions. NeuroRehabilitation. 2003;18:135–46.

Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Burns R, Graney MJ, Zuber J. Translation of a dementia caregiver support program in a health care system--REACH VA. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):353–9.

Feeney Mahoney DM, Tarlow B, Jones RN, Tennstedt S, Kasten L. Factors affecting the use of a telephone-based intervention for caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;7:139–48.

Glueckauf RL, Ketterson TU, Loomis JS, Dages P. Online support and education for dementia caregivers: overview, utilization, and initial program evaluation. Telemed J E Health. 2004;10(2):223–32.

•• Brearly TW, et al. Neuropsychological est administration by videoconference: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2017;27(2):174–86 Systematic review and meta-analysis to examine differences between administrative of neuropsychological tests using videoconferencing and in-person, reporting consistency across platforms with more varied results in studies with older adults and slower network connection. Includes consideration for development of best practices and reimbursement.

Harrell KM, Wilkins SS, Connor MK, Chodosh J. Telemedicine and the evaluation of cognitive impairment: the additive value of neuropsychological assessment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(8):600–6.

Martin-Khan M, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of telegeriatrics for the diagnosis of dementia via video conferencing. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(5):487 e19–24.

Parikh M, Grosch MC, Graham LL, Hynan LS, Weiner M, Shore JH, et al. Consumer acceptability of brief videoconference-based neuropsychological assessment in older individuals with and without cognitive impairment. Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;27(5):808–17.

Lacny C, et al. Does day length affect cognitive performance in memory clinic patients? Can J Neurol Sci/J Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques. 2014;38(03):461–4.

Shores MM, Ryan-Dykes P, Williams RM, Mamerto B, Sadak T, Pascualy M, et al. Identifying undiagnosed dementia in residential care veterans: comparing telemedicine to in-person clinical examination. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(2):101–8.

•• Powers B, et al. Creation of an Interprofessional Teledementia Clinic for Rural Veterans: Preliminary Data. Models Geriatric Care Qual Improv Program Dissemination. 2017;65(5):1092–9 Describes use of clinical video telehealth to deliver dementia specialty care between a VA medical center and community-based outpatient clinics for veterans with dementia.

•• Dang S, Gomez-Orozco CA, van Zuilen M, Levis S. Providing dementia consultations to veterans using clinical video telehealth: results from a clinical demonstration project. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(3):203–9 Examines the feasibility, acceptability, and impact of a clinical demonstration project within Veterans Affairs in which video-conferencing is used to deliver clinical consultation to veterans with dementia or cognitive complaints, finding telehealth-facilitated clinical consultation may aid timely evaluation and management of rural veterans with dementia and their families.

Morgan DG, Crossley M, Kirk A, D’Arcy C, Stewart N, Biem J, et al. Improving access to dementia care: development and evaluation of a rural and remote memory clinic. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(1):17–30.

Morgan DG, Crossley M, Kirk A, McBain L, Stewart NJ, D’Arcy C, et al. Evaluation of telehealth for preclinic assessment and follow-up in an interprofessional rural and remote memory clinic. J Appl Gerontol. 2011;30(3):304–31.

Azad N, et al. Telemedicine in a rural memory disorder clinic-remote management of patients with dementia. Can Geriatr J. 2012;15(4):96–100.

Barton CM, Rothlind J, Yaffe K. Video-telemedicine in a memory disorders clinic: evaluation and management of rural elders with cognitive impairment. Telemed J E Health. 2011;17:789–93.

Chang W, Homer M, Rossi M. Use of clinical video telehealth as a tool for optimizing medications for rural older veterans with dementia. Geriatrics. 2018;3(3):E44.

• Burton RL, O'Connell ME. Telehealth rehabilitation for cognitive impairment: randomized controlled feasibility trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7(2):e43 Compared goal-oriented cognitive rehabilitation delivered in person with videoconferencing to determine feasibility of telehealth-delivered cognitive rehabilitation, reporting intervention was feasible but required increased involvement of clients and caregivers.

•• Crotty M, Killington M, van den Berg M, Morris C, Taylor A, Carati C. Telerehabilitation for older people using off-the-shelf applications: acceptability and feasibility. J Telemed Telecare. 2014;20(7):370–6 Examined the feasibility of telerehabilitation into the home as an alternative to conventional ambulatory rehabilitation for patients who were post-stroke, post-fracture, or prolonged hospital admission, or who had a recent injury, fall or other hospitalization.

Sanford JA, et al. A comparison of televideo and traditional in-home rehabilitation in mobility impaired older adults. Physical Occupational Therapy In Geriatrics. 2009;25(3):1–18.

Koh GC, et al. Singapore tele-technology aided rehabilitation in stroke (STARS) trial: protocol of a randomized clinical trial on tele-rehabilitation for stroke patients. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:161.

•• Chumbler NR, et al. A randomized controlled trial on stroke telerehabilitation: The effects on falls self-efficacy and satisfaction with care. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(3):139–43 Presents data from a prospective, randomized, multi-site, single-blinded trial at Veterans Affairs of a multifaceted stroke telerehabilitation (STeleR) intervention on falls-related self-efficacy and satisfaction with care.

•• Ownsworth T, et al. Efficacy of telerehabilitation for adults with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33(4):E33–46 Review of telerehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury, including 10 randomized controlled trials; reports efficacy in general but primarily for telephone-based interventions.

•• Pastora-Bernal JM, Martín-Valero R, Barón-López FJ, Estebanez-Pérez MJ. Evidence of benefit of telerehabitation after orthopedic surgery: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(4):e142 Systematic review of the quality of telerehabilitation after surgical procedures for orthopedic conditions, concluding from their review of fifteen included studies that evidence for efficacy is inconclusive.

•• Cottrell MA, et al. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(5):625–38 Evaluates the effectiveness of videoconferenced telerehabilitation for musculoskeletal conditions, finding from their review of thirteen studies that telerehabilitation appears effective at improving physical function.

Choi J, Hergenroeder AL, Burke L, Dabbs ADV, Morrell M, Saptono A, et al. Delivering an in-home exercise program via telerehabilitation: a pilot study of Lung Transplant Go (LTGO). Int J Telerehabil. 2016;8(2):15–26.

Hoffmann T, Russell T. Pre-admission orthopaedic occupational therapy home visits conducted using the internet. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:83–7.

• Nix J, Comans T. Home Quick – occupational therapy home visits using mHealth, to facilitate discharge from acute admission back to the community. Int J Telerehabil. 2017;9(1):47–54 Presented findings from a technology-facilitated home visit pre-discharge (Home Quick) program, concluding that it resulted in increased home visits conducted prior to discharge and significantly more patients seen post-discharge.

Serwe KM, Hersch GI, Pickens ND, Pancheri K. Caregiver perceptions of a telehealth wellness program. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71(4):7104350010p1–5.

Boyle A, VA announces new partnerships to expand telehealth services, in U.S. Medicine.

•• Brown EL, Ruggiano N, Li J, Clarke PJ, Kay ES, Hristidis V. Smartphone-based health technologies for dementia care: opportunities, challenges, and current practices. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38(1):73–91 Describes smartphone-based interventions for persons with dementia and their caregivers, highlighting the limited functionality of current offerings compared to the needs of patients of families.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Austrom MG, Geros KN, Hemmerlein K, McGuire SM, Gao S, Brown SA, et al. Use of a multiparty web based videoconference support group for family caregivers: innovative practice. Dementia (London). 2015;14(5):682–90.

Czaja SJ, Loewenstein D, Schulz R, Nair SN, Perdomo D. A videophone psychosocial intervention for dementia caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(11):1071–81.

Damianakis T, Wilson K, Marziali E. Family caregiver support groups: spiritual reflections' impact on stress management. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(1):70–6.

Dowling GA, Merrilees J, Mastick J, Chang VY, Hubbard E, Moskowitz JT. Life enhancing activities for family caregivers of people with frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28(2):175–81.

Griffiths PC, Whitney MK, Kovaleva M, Hepburn K. Development and implementation of tele-savvy for dementia caregivers: a Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Demonstration Project. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):145–54.

Griffiths PC, Kovaleva M, Higgins M, Langston AH, Hepburn K. Tele-savvy: an online program for dementia caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2018;33(5):269–76.

Kovaleva M, Blevins L, Griffiths PC, Hepburn K. An online program for caregivers of persons living with dementia: lessons learned. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38(2):159–82.

Lindauer A, Seelye A, Lyons B, Dodge HH, Mattek N, Mincks K, et al. Dementia care comes home: patient and caregiver assessment via telemedicine. Gerontologist. 2017;57(5):e85–93.

Lindauer A, et al. "It took the stress out of getting help": The STAR-C-Telemedicine Mixed Methods Pilot. Care Wkly. 2018;2:7–14.

Meyer AM, Getz HR, Brennan DM, Hu TM, Friedman RB. Telerehabilitation of anomia in primary progressive aphasia. Aphasiology. 2016;30(4):483–507.

Rogalski EJ, Saxon M, McKenna H, Wieneke C, Rademaker A, Corden ME, et al. Communication bridge: a pilot feasibility study of Internet-based speech-language therapy for individuals with progressive aphasia. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2016;2(4):213–21.

van Leynseele, J., et al., STAR: a dementia-specific training program for staff in assisted living residences: Nancy Morrow-Howell, MSW, PhD, Editor. Gerontologist, 2005. 45(5): p. 686–693.

Teri L, McCurry SM, Logsdon R, Gibbons LE. Training community consultants to help family members improve dementia care: a randomized controlled trial. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(6):802–11.

Kovaleva MA, Bilsborough E, Griffiths PC, Nocera J, Higgins M, Epps F, et al. Testing tele-savvy: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Res Nurs Health. 2018;41(2):107–20.

•• Banbury A, Nancarrow S, Dart J, Gray L, Parkinson L. Telehealth interventions delivering home-based support group videoconferencing: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(2):e25 Reviews the feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness, and implementation of extent practitioner-facilitated group videoconferencing for support, education (or both) delivered into the home of patients contending with chronic conditions.

Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, Uscher-Pines L, Rose S, Landon BE, et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):909–17.

• Yilmaz SK, et al. An economic cost analysis of an expanding, multi-state behavioural telehealth intervention. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;1:1357633X18774181 Compares the travel cost of a multi-state telepsychiatry intervention to that of in-person, concluding that telemedicine is associated with decreased costs. Authors highlight implications for broader implementation of telemedicine.

• Burton R, O'Connell ME, Morgan DG. Exploring interest and goals for videoconferencing delivered cognitive rehabilitation with rural individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. NeuroRehabilitation. 2016;39(2):329–42 Qualitative study of rural persons with dementia's interest in video-delivered cognitive treatment and goals for treatment, with the majority interested in the video option.

•• Struckmeyer LR, Pickens ND. Home modifications for people with Alzheimer's disease: a scoping review. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70(1):7001270020p1–9 Scoping review of home modifications and Alzheimer's disease (AD) that included seventeen articles; highlights the inclusion of cognitive strategies as distinct in AD home modifications, and the need for assessment strategies and more work to address the needs of of late-stage dementia and persons living alone.

•• Jensen L, Padilla R. Effectiveness of environment-based interventions that address behavior, perception, and falls in people with Alzheimer's disease and related major neurocognitive disorders: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71(5):7105180030p1–7105180030p10 Systematic review of the efficacy of environment-based interventions for behavior, perception, and falls for persons with AD and Related Dementias (ADRD); of 42 included studies, evidence supports client-centered strategies to address behavior, with mixed evidence for strategies such as environmental design and wander gardens.

•• Piersol CV, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for caregivers of people with Alzheimer's disease and related major neurocognitive disorders: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2017;71(5):7105180020p1–7105180020p10 Systematic review of evidence supporting caregivers; of 43 included studies, strong evidence exists for psychoeducational programs, cognitive reframing, communication skills, mindfulness-based training, and facilitated caregiver support groups to improve caregiver outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Nicole Bookout, Science Research & Instruction Librarian at Tufts University, for assisting with search design and completing searches.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Megan E. Gately, Scott A. Trudeau, and Lauren R. Moo each declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gately, M.E., Trudeau, S.A. & Moo, L.R. In-Home Video Telehealth for Dementia Management: Implications for Rehabilitation. Curr Geri Rep 8, 239–249 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-019-00297-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-019-00297-3