Summary

Background.

For critical ill patients, the use of a blood gas analyzer (BGA) rather than central laboratory instruments (CL) for biochemical and hematological parameters is common due to more convenient monitoring. Potential significant differences between the methods could be misleading. This study aimed to confirm the agreement between the BGA and CL results and to analyze the effects of inter-methods bias on medical decisions.

Methods.

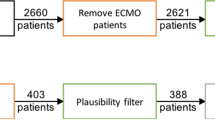

Blood samples from arterial lines were collected in the Cardio Surgical Intensive Care Unit simultaneously for gas analyses (RapidPoint 500, Siemens, Erlangen, Germania) and CL (\(D{\times}C\) 880i and \(D{\times} H\) 800 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) determinations. Methods were compared using Passing-Bablok (PB) regression and Bland Altman analysis. Positive and negative false results of the BGA tests were calculated considering the reference CL tests at critical values for glucose (70, 150 and 180 mg/dL), hemoglobin (7 and 10 g/dL), potassium (3.5–5 mEq/L), sodium (135–145 mEq/L) and lactate (6.5–19.3 mg/dL).

Results.

PB regression did not show a significant deviation from linearity for all of the parameters; proportional and constant differences were observed for hemoglobin, potassium, and lactate. Intercept and slope of sodium and glucose regression line were significantly different from zero and one respectively. Only the potassium, lactate, and glucose bias estimations were acceptable. However, for hemoglobin it was possible to significantly lower negative false results using PB transformed data.

Conclusions.

Only the glucose, potassium and lactate results, using both methods, were interchangeable; however the hemoglobin adjustment of BGA values based on PB regression might represent a safer solution.

Riassunto

Premesse.

L’utilizzo dell’emogasanalizzatore (BGA) anziché gli strumenti di laboratorio (CL) per i dosaggi di alcuni parametri di chimica clinica ed ematologia è pratica comune nei reparti con pazienti critici, dal momento che ne semplifica il monitoraggio. Le potenziali differenze significative inter-metodo possono però portare a un’errata interpretazione dei dati. Lo scopo di questo lavoro è stato verificare l’agreement delle misure tra BGA e CL e analizzare gli eventuali effetti del bias inter-metodo sulle decisioni cliniche.

Metodi.

Campioni di sangue arterioso sono stati raccolti su pazienti della Terapia Intensiva della Cardiochirurgia sia per il dosaggio su BGA (RapidPoint 500, Siemens, Erlanger, Germania) che su CL (\(\mathrm{D}{\times}\mathrm{C}\) 880i e \(\mathrm{D}{\times}\mathrm{H}\) 800 (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA)). Per il confronto tra metodi sono state utilizzate la regressione di Passing-Bablok (PB) e l’analisi di Bland-Altman. Il conteggio dei falsi negativi e positivi utilizzando BGA è stato fatto ai valori critici di glucosio (70, 150 e 180 mg/dL), potassio (3,5–5 mEq/L), sodio (135–145 mEq/L), emoglobina (7 e 10 g/dL) e lattato (6,5–19,3 mg/dL), considerando come metodi di riferimento gli strumenti di laboratorio.

Risultati.

La regressione di PB non ha evidenziato scostamenti significativi dalla linearità per tutti i parametri; differenze proporzionali e costanti sono state osservate per l’emoglobina, il potassio e il lattato. L’intercetta e la slope della retta di regressione di sodio e glucosio erano significativamente diverse da 0 e 1 rispettivamente. Solo i bias % di potassio, lattato e glucosio erano accettabili. Tuttavia, per l’emoglobina è stato possibile ridurre significativamente i falsi negativi utilizzando i dati del BGA trasformati dalla regressione di PB.

Conclusioni.

I risultati di glucosio, potassio e lattato sono gli unici che possono essere considerati intercambiabili tra i due metodi; tuttavia la trasformazione dei valori dell’emoglobina su BGA attraverso un fattore calcolato sulla base della retta di regressione di PB può rappresentare una valida soluzione.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ferraris VA, Brown JR, Despotis GJ et al. (2011) 2011 update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg 91:944–982

Hajjar LA, Almeida JP, Fukushima JT et al. (2013) High lactate levels are predictors of major complications after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 146:455–460

Jacobi J, Bircher N, Krinsley J et al. (2012) Guidelines for the use of an insulin infusion for the management of hyperglycemia in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 40:3251–3276

Girish G, Agarwal S, Satsangi DK et al. (2014) Glycemic control in cardiac surgery: rationale and current evidence. Ann Card Anaesth 17:222–228

Hargraves JD (2014) Glycemic control in cardiac surgery: implementing an evidence-based insulin infusion protocol. Am J Crit Care 23:250–258

Bloom BM, Connor H, Benton S et al. (2014) A comparison of measurements of sodium, potassium, haemoglobin and creatinine between an Emergency Department-based point-of-care machine and the hospital laboratory. Eur J Emerg Med 21:310–313

Budak YU, Huysal K, Polat M (2012) Use of a blood gas analyzer and a laboratory autoanalyzer in routine practice to measure electrolytes in intensive care unit patients. BMC Anesthesiol 12:17–19

Leino A, Kurvinen K (2011) Interchangeability of blood gas, electrolyte and metabolite results measured with point-of-care, blood gas and core laboratory analyzers. Clin Chem Lab Med 49:1187–1191

Bland JM, Altman DG (2012) Agreed statistics. Measurement method comparison. Anesthesiology 116:182–185

Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1:307–310

Klee GG (2010) Establishment of outcome-related analytic performance goals. Clin Chem 56:714–722

Jay DW (2011) Method comparison: where do we draw the line? Clin Chem Lab Med 49:1089–1090

Westgard JO (2012) Desirable specifications for total error, imprecision, and bias, derived from intra- and inter-individual biologic variation. www.westgard.com/biodatabase1.htm (Accessed January 2016)

De Koninck AS, De Decker K, Van Bocxlaer J et al. (2012) Analytical performance evaluation of four cartridge-type blood gas analyzers. Clin Chem Lab Med 50:1083–1091

Plebani M (2009) Does POCT reduce the risk of error in laboratory testing? Clin Chim Acta 404:59–64

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Human and animal rights

This study was performed according to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans.

Informed consent

All patients provided informed consent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stenner, E., Gon, L., Dreas, L. et al. Blood gas analyzer and central laboratory glucose, sodium, potassium, lactate and hemoglobin values: differences between methods and their effect on medical outcome. Riv Ital Med Lab 12, 49–53 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13631-016-0111-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13631-016-0111-0