Abstract

Introduction

Teneligliptin, an antidiabetic agent classified as a class III dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, has a unique structural feature that provides strong binding to DPP-4 enzymes. We investigated the efficacy and safety of switching patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who had inadequate glycemic control on a stable dose of other DPP-4 inhibitors to teneligliptin.

Methods

Patients with T2DM whose glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were ≥ 7% despite taking DPP-4 inhibitors other than teneligliptin, with or without other hypoglycemic agents, for at least 3 months were enrolled. The DPP-4 inhibitors taken before participating in the study were switched to 20 mg qd teneligliptin, and this was to be maintained for 52 weeks. The primary end point was the change in HbA1c levels after 12 weeks. Metabolic parameters including fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and blood lipids were assessed also. To assess safety, adverse and hypoglycemic events were monitored. The data from baseline to week 12 were used for analysis in this interim report.

Results

The mean change in HbA1c levels from baseline to week 12 was − 0.44%. At week 12, the percentage of patients achieving HbA1c < 7.0% was 31.6% and that of achieving HbA1c < 6.5% was 11.4%, respectively. In 41.2% of patients, the HbA1c levels decreased by at least 0.5% at 12 weeks. The mean change in FPG levels from baseline to week 12 was − 11.5 mg/dl. No severe hypoglycemia was reported.

Conclusion

After switching to teneligliptin, HbA1c levels decreased significantly in patients with T2DM inadequately controlled with other DPP-4 inhibitors.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03793023.

Funding

Handok Inc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 8.8% of adults (20–79 years) were estimated to have diabetes worldwide in 2017 [1]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which accounts for 90% of all diabetes cases, is mainly caused by insulin resistance and insulin deficiency. Impaired insulin action and lack of insulin secretion result in imbalanced glucose metabolism; then, chronic hyperglycemia resulting from imbalanced glucose metabolism induces cellular damage that mediates micro- and macrovascular complications [2]. Therefore, tight glycemic control is warranted to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with T2DM. Due to the progressive nature of the disease, glycemic control gets worse despite careful management, and more intensive pharmacologic therapies are required over time.

Current practice guidelines recommend metformin monotherapy as first-line pharmacologic treatment [3], which should be intensified if the glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) target is not achieved after 3 months. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors are one of the recommended treatment options for T2DM. As they work in a glucose-dependent manner, DPP-4 inhibitors are known to lower HbA1c levels significantly with little risk of hypoglycemia. Since the first approval of an agent of this class in 2006, the use of DPP-4 inhibitors has increased remarkably. They are the most popular agents used as add-on therapy to metformin or sulfonylureas, and their use as monotherapy agents has gradually increased over the past several years [4]. It is known that DPP-4 has multiple binding sites and that the difference in binding mode between DPP-4 inhibitors is related to the potency and selectivity of the drugs [5]. Teneligliptin, classified as a class III DPP-4 inhibitor, has a unique structural feature that provides strong binding to DPP-4 enzymes compared with other gliptins [6]. In addition, pleiotropic benefits of teneligliptin have been reported, including improvement in the endothelial function and lipid profile, which are important factors in the management of metabolic diseases [7, 8].

A meta-analysis revealed that DPP-4 inhibitors offered a 0.65% reduction in HbA1c levels [9]. A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that teneligliptin significantly reduced HbA1c levels by 0.82% (95% CI, − 0.91 to − 0.72) compared with placebo [10]. After 24 weeks of teneligliptin therapy, mean absolute HbA1c level reductions in Korean patients were − 0.94% when used as mono and dual therapy, respectively [11]. Compared with the HbA1c level changes observed in the previous studies of DPP-4 inhibitors [12, 13], these somewhat larger changes suggest that teneligliptin may offer greater efficacy than other DPP-4 inhibitors.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of switching therapy to teneligliptin in patients with T2DM who had inadequate glycemic control despite treatment with a stable dose of other DPP-4 inhibitors. This study has been planned to follow up participants from baseline to 52 weeks after enrollment, and it is ongoing. Here, we report the 12-week interim results from the study.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

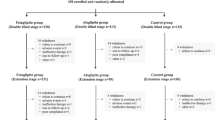

This was a multicenter, open-label, single-arm, prospective observational study in which 105 sites across Korea participated (ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT03793023). The study was initiated in 2017 and is estimated to be finished by 2019. Patients with T2DM whose HbA1c levels were ≥ 7% despite taking other DPP-4 inhibitors with or without other hypoglycemic agents for at least 3 months were screened and enrolled. Patients were eligible for this trial if they met all the following inclusion criteria: men and women with T2DM; age ≥ 19 years; had been diagnosed with T2DM at least 3 months before enrollment; had received stable doses of DPP-4 inhibitors for at least 12 weeks; had HbA1c levels > 7.0%; had been judged as suitable for changing DPP-4 inhibitors by the investigator. Excluded were patients with contraindications to teneligliptin or patients who had received prior treatment with teneligliptin. Pregnant or lactating women were also excluded. After completion of the baseline assessment, their DPP-4 inhibitors were switched to teneligliptin. Patients were to take teneligliptin (20 mg per day) from the day of study enrollment until week 52 (Fig. 1). Baseline concomitant antidiabetic regimens were to be maintained throughout the study. The follow-up visits were scheduled at 12, 24, and 52 weeks after enrollment. At each visit, patients’ HbA1c levels, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels, serum lipids levels, weight, body mass index (BMI), and adverse events (AEs) were assessed.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent before participating in the study, and the study was initiated after approval of the study protocol by the institutional review board at each site or by the local institutional review boards (Supplementary Table S2), including Ajou University Hospital IRB (AJIRB-MED-OBS-15-410).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of this study was the mean changes in HbA1c levels from baseline to week 12. The secondary outcomes included the mean changes in HbA1c levels from baseline to week 24 and 52. The mean changes in the levels of FPG, serum lipids [i.e., total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides], weight, and BMI from baseline to week 12, 24, and 52 were also secondary outcomes. The percentage of patients with HbA1c levels < 7.0% or < 6.5% at week 12, 24, and 52, the percentage of patients with an HbA1c reduction of ≥ 0.3% or ≥ 0.5% from baseline to week 12, 24, and 52, and the results of the safety assessment were included in the secondary outcomes. The data from baseline to week 12 were used for analysis in this interim report.

Safety was assessed based on the incidence of AEs and hypoglycemic episodes. Regarding hypoglycemia, patients were asked to describe their experience of hypoglycemic episodes. Any patient who reported a self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG) level < 70 mg/dl, with or without one of the following symptoms: sweating, fatigue, dizziness, headache, tremor, hunger, irritability, and seizure, was considered to have a hypoglycemic episode. Severe hypoglycemia was considered if the patients required third-party assistance, administration of glucagon, or fast-acting carbohydrate for recovery.

Statistical Methods

The sample size was calculated to detect 0.3% of change in HbA1c levels after switching to teneligliptin assuming a standard deviation of 0.65% based on the result of a teneligliptin phase III study conducted in Korea [14]. The null hypotheses were that there would be no difference in changes in HbA1c levels after 12 weeks of switching from each of the six DPP-4 inhibitors or from overall DPP-4 inhibitors to teneligliptin. Individual paired t-tests were performed repeatedly to reject at least one null hypothesis of the seven null hypotheses. This interim analysis includes 1732 patients who completed the second visit (week 12) as of 30 July 2017.

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) are used to describe continuous variables of baseline demographic and biochemical parameters, and counts with percentages are presented for categorical variables of baseline demographic and biochemical parameters. As for the primary outcome analyses (i.e., analysis for the changes in HbA1c level from baseline to week 12), conclusions of statistical significance were drawn based on Hochberg’s step-up method for controlling the overall type I error to be 0.5%. No correction for multiplicity was performed in the analyses of other outcomes. The results from individual paired t-test were presented at a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

Results

Patient Disposition, Demographics, and Clinical Characteristics

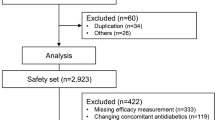

Of the 1947 patients who were screened, 1888 were enrolled in this study, and 1732 completed the visit at 12 weeks as of 30 July 2017. Two analysis sets, an efficacy set and a safety set, were predefined for the analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes, respectively. The efficacy set comprised 1426 patients who were enrolled and reported HbA1c levels at least once after receiving the study treatment. The safety set included 1732 patients who received study treatment at least once (Fig. 2).

The baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 62.8 years, and the percentage of the patients aged ≥ 65 years was 45.4%. The mean duration of T2DM was 8.2 years, and the mean baseline HbA1c level was 7.9%. There were six DPP-4 inhibitors that were taken by the enrolled patients prior to baseline: linagliptin (38.8%), sitagliptin (26.6%), vildagliptin (16.0%), gemigliptin (8.1%), saxagliptin (6.6%), and alogliptin (4.0%), which are listed in the order of most to least used. As for the antidiabetic therapies used concomitantly with teneligliptin, metformin monotherapy was the most used therapy (49.6%) followed by metformin and sulfonylurea dual therapy (19.8%), other therapies (5.0%), insulin therapy (4.3%), and sulfonylurea monotherapy (2.1%). The duration of patients’ treatment with concomitant antidiabetics before they participated in this study is presented according to their prior gliptin levels in Supplementary Table S1.

Efficacy

The mean change in HbA1c levels from baseline to week 12 was − 0.44% (P < 0.0001) in patients overall (Fig. 3a). Subgroup analysis according to baseline HbA1c levels (≥ 8.0% vs. < 8.0%) showed that the mean decrease in HbA1c levels was greater in patients with HbA1c levels ≥ 8.0% at baseline than in patients with HbA1c levels < 8.0% (− 0.74% vs. − 0.30%, Fig. 3b). The mean changes in HbA1c levels were also evaluated in the six patient groups in which the patients were subdivided according to their prior DPP-4 inhibitor therapies. There were significant decreases from baseline to week 12 mean HbA1c levels in the patients switched from linagliptin, sitagliptin, vildagliptin, and saxagliptin to teneligliptin. Though mean HbA1c levels also decreased from baseline in the patients switched from alogliptin or gemigliptin to teneligliptin, this was not statistically significant (Fig. 3a and Table 2).

HbA1c outcomes after 12-week treatment of teneligliptin. a Changes in HbA1c levels at week 12. b Changes in HbA1c levels according to baseline levels. c Percentages of patients achieving target HbA1c levels. d Percentages of patients with meaningful decrease in HbA1c levels. aStatistically significant according to the Hochberg method. bP < 0.05

With respect to the responder rate, the percentage of patients achieving HbA1c levels < 7.0% at week 12 was 31.6% (452/1426) and that of achieving HbA1c levels < 6.5% was 11.4% (162/1426) (Fig. 3c). At week 12, the percentages of patients with a decrease of at least 0.3% and 0.5% in HbA1c levels were 57.9% (825/1426) and 41.2% (587/1426), respectively (Fig. 3d).

After 12 weeks of switching to teneligliptin, statistically significant changes in mean FPG levels, weight, BMI, and serum lipid levels were observed (Table 2). The mean FPG level was reduced from 169.2 mg/dl to 159.5 mg/dl in patients overall with a mean change of − 11.5 mg/dl (P < 0.0001). Taking into account the six prior therapies, patients who switched from linagliptin, sitagliptin, and vildagliptin showed a significant reduction in FPG levels (P < 0.05), and the others showed decreasing trends that were not statistically significant. The weight decreased by a mean of 0.4 kg (P < 0.0001) from baseline, and the mean BMI also decreased by 0.1 kg/m2 (P < 0.0001). Among the serum lipid parameters, total cholesterol and LDL-C levels decreased from baseline to week 12 (P < 0.05).

Safety

A total of 63 AEs were reported in 51 patients from the safety set with an incidence rate of 2.9% (Table 3). Dizziness (0.3%) and headache (0.3%) were the most commonly reported AEs. All reported AEs were mild to moderate in severity. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs), the AEs that were assumed to be related to the study treatment, were reported in six patients (0.4%). Of the seven serious adverse events reported in six patients, none was assessed to be related to the study treatment. Five patients withdrew from this study before week 12 because of AEs.

Hypoglycemia was reported in six patients (0.4%) at 12 weeks. The reported hypoglycemic symptoms were dizziness (0.4%, 4/1732), sweating (0.1%, 1/1732), fatigue (0.1%, 1/1732), headache (0.1%, 2/1732), tremor (0.1%, 1/1732), and hunger (0.1%, 1/1732). No severe hypoglycemia was reported.

Discussion

In the present study, switching therapy from other DPP-4 inhibitors to teneligliptin lowered HbA1c levels by 0.44% from baseline to week 12 in patients with inadequate glycemic control despite treatment with other DPP-4 inhibitors. FPGs level also decreased by 11.5 mg/dl after 12 weeks.

The decrease of 0.44% in HbA1c levels observed in this study was comparable to the known minimal clinically meaningful difference in HbA1c level, which is regarded as a conservative estimate for the magnitude of the treatment effect in the T2DM trials [15, 16]. Based on the results of a few head-to-head trials or meta-analyses comparing the efficacy between DPP-4 inhibitors, there is general consensus that the HbA1c-lowering effects of gliptins are broadly similar [9, 12, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. However, here we observed that HbA1c levels decreased further after switching to teneligliptin, which belongs to the same class of drugs. Moreover, the percentage of patients who achieved HbA1c levels < 7.0% were comparable to those reported in previous studies with similar baseline HbA1c levels [12, 24].

Given that the patient population of this study comprised T2DM patients whose HbA1c levels were inadequately controlled with prior gliptin therapies, it is supposed that the differences in binding affinity and potency between gliptins are plausible causes for these findings. Indeed, it was shown that significant differences in the degree of DPP-4 inhibition among DPP-4 inhibitors exist [25], and a correlation between plasma DPP-4 inhibition and glucose-lowering was found [26]. In this context, several studies showed that changes in HbA1c levels were greater after treatment with vildagliptin than other gliptins, supporting the notion that the glucose-lowering effects of DPP-4 inhibitors are significantly different [27,28,29,30]. As mentioned before, teneligliptin was found to bind more tightly to the DPP-4 enzyme than other gliptins because of their “J-shaped” structure formed by five rings [31]. The long-time and strong binding to the DPP-4 enzyme makes teneligliptin more potent and elicits a further decrease in HbA1c levels after switching to it. In this study, we provide additional support for the assumption that there may be differences in efficacy among DPP-4 inhibitors by showing a significant decrease in HbA1c levels after changing gliptins to teneligliptin. However, it is still necessary to investigate whether clinically meaningful differences due to different binding modes of teneligliptin and other gliptins to the DPP-4 enzyme exist. In a recent study by Kim et al. [32], although the patients’ baseline characteristics were somewhat different from those of our study, teneligliptin was not inferior to sitagliptin in terms of glycemic control. More head-to-head, comparative trials are needed to confirm the differences in efficacy between these DPP-4 inhibitors.

We expect that our study results will support another treatment option: switching of agents within the same class before adding other classes. Though present guidelines suggest adding other hypoglycemic agents of different classes to existing therapies of patients who do not achieve adequate glycemic control, this may increase the pill and economic burdens, which are both factors that affect patient compliance. Switching agents within the same class could be a treatment option in this case. One retrospective study reported that switching from sitagliptin (50 mg) to vildagliptin (100 mg) significantly reduced HbA1c levels after 24 weeks of treatment, while increasing the sitagliptin dose from 50 mg to 100 mg failed to significantly reduce HbA1c levels [33]. Likewise, our study showed that switching from other gliptins to teneligliptin significantly reduced HbA1c levels after 12 weeks of treatment. To generalize our findings, it might be useful to investigate whether switching patients from teneligliptin to other gliptins improves HbA1c values or not.

Regarding the other metabolic parameters such as weight, BMI, or lipid parameters, no clinically meaningful change was observed in this study, though there were favorable trends, some of which were statistically significant. Switching to teneligliptin was well tolerated. No unexpected AEs or severe hypoglycemia were reported, and all AEs including hypoglycemia were mild to moderate in severity.

There are some limitations in this study. One is that the current study did not include a control group for comparison. Thus, we cannot be sure whether the observed values are due to the treatment itself or not. Because of the nature of observational studies, there may be many confounding factors affecting the study outcomes such as lifestyle modification or compliance to the study drug. In addition, it is possible that seasonal variations in HbA1c could affect the results of this study [34]. A well-controlled, randomized study is warranted to overcome this limitation. The other limitation is that because we report interim findings of the study, it is particularly difficult to ascertain whether these findings will be maintained during a 1-year period of follow-up.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that HbA1c levels decreased significantly after switching patients with T2DM inadequately controlled with other DPP-4 inhibitors to teneligliptin. Taken together, we suppose that the HbA1c decreases observed in this study could be evidence of the superior potency of teneligliptin. Further studies are required to confirm our findings.

References

International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 8th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2017.

Campos C. Chronic hyperglycemia and glucose toxicity: pathology and clinical sequelae. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(6):90–7.

Care D, Suppl SS. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care [Internet]. 2019;42(Supplement 1):S90–102. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S009.

Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes Fact Sheet in Korea. 2018.

Kim SH, Yoo JH, Lee WJ, Park CY. Gemigliptin: an update of its clinical use in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J. 2016;40(5):339–53.

Maladkar M, Sankar S, Kamat K. Teneligliptin: heralding change in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Mellit. 2016;06(02):113–31.

Kusunoki M, Sato D, Nakamura T, Oshida Y, Tsutsui H, Natsume Y, et al. DPP-4 Inhibitor teneligliptin improves insulin resistance and serum lipid profile in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Drug Res (Stuttg). 2015;65(10):532–4.

Hashikata T, Yamaoka-Tojo M, Kakizaki R, Nemoto T, Fujiyoshi K, Namba S, et al. Teneligliptin improves left ventricular diastolic function and endothelial function in patients with diabetes. Heart Vessels. 2016;31(8):1303–10.

Park H, Park C, Kim Y, Rascati KL. Efficacy and Safety of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes: Meta-Analysis. Ann Pharmacother [Internet]. 2012;46(11):1453–69. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1R041.

Li X, Huang X, Bai C, Qin D, Cao S, Mei Q, et al. Efficacy and safety of teneligliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:499.

Hong S, Park CY, Han KA, Chung CH, Ku BJ, Jang HC, et al. Efficacy and safety of teneligliptin, a novel dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 24-week multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(5):528–32.

Craddy P, Palin HJ, Johnson KI. Comparative effectiveness of dipeptidylpeptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and mixed treatment comparison. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5(1):1–41.

Nishio S, Abe M, Ito H. Anagliptin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: safety, efficacy, and patient acceptability. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targ Ther. 2015;8:163–71.

Kim MK, Rhee E-J, Han KA, Woo AC, Lee M-K, Ku BJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of teneligliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, combined with metformin in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 16-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(3):309–12.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products in the treatment or prevention of diabetes mellitus. 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-treatment-prevention-diabetes-mellitus_en.pdf. Accessed 4 Jan 2019.

U.S. Department of Health and Human, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Guidance for industry. Diabetes mellitus: developing drugs and therapeutic biologics for treatment and prevention. 2008. https://www.fda.gov/media/71289/download. Accessed 4 Jan 2019.

Munir KM, Lamos EM. Diabetes type 2 management: what are the differences between DPP-4 inhibitors and how do you choose? Expert Opin Pharmacother [Internet]. 2017;18(9):839–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2017.1323878.

Deacon CF, Holst JJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: comparison, efficacy and safety. Expert Opin Pharmacother [Internet]. 2013;14(15):2047–58. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2013.824966.

Inagaki N, Onouchi H, Maezawa H, Kuroda S, Kaku K. Once-weekly trelagliptin versus daily alogliptin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol [Internet]. 2015;3(3):191–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70251-7.

Hong SM, Park CY, Hwang DM, Han KA, Lee CB, Chung CH, et al. Efficacy and safety of adding evogliptin versus sitagliptin for metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: a 24-week randomized, controlled trial with open label extension. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19(5):654–63.

Li CJ, Liu XJ, Bai L, Yu Q, Zhang QM, Yu P, et al. Efficacy and safety of vildagliptin, Saxagliptin or Sitagliptin as add-on therapy in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with dual combination of traditional oral hypoglycemic agents. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2014;6(1):1–9.

Scheen AJ, Charpentier G, Östgren CJ, Hellqvist Å, Gause-Nilsson I. Efficacy and safety of saxagliptin in combination with metformin compared with sitagliptin in combination with metformin in adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev [Internet]. 2010;26(7):540–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.1114.

Rhee EJ, Lee WY, Min KW, Shivane VK, Sosale AR, Jang HC, et al. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor gemigliptin compared with sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin alone. Diabetes, Obes Metab [Internet]. 2013;15(6):523–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.12060.

Esposito K, Cozzolino D, Bellastella G, Maiorino MI, Chiodini P, Ceriello A, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and HbA1c target of < 7% in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(7):594–603.

Tatosian DA, Guo Y, Schaeffer AK, Gaibu N, Popa S, Stoch A, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with saxagliptin, sitagliptin, or vildagliptin. Diabetes Ther. 2013;4(2):431–42.

Berger JP, SinhaRoy R, Pocai A, Kelly TM, Scapin G, Gao Y-D, et al. A comparative study of the binding properties, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitory activity and glucose-lowering efficacy of the DPP-4 inhibitors alogliptin, linagliptin, saxagliptin, sitagliptin and vildagliptin in mice. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab [Internet]. 2018;1(1):e00002. https://doi.org/10.1002/edm2.2.

Signorovitch JE, Wu EQ, Swallow E, Kantor E, Fan L, Gruenberger J-B. Comparative efficacy of vildagliptin and sitagliptin in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Drug Investig. 2011;31(9):665–74.

Tang YZ, Wang G, Jiang ZH, Yan TT, Chen YJ, Yang M, et al. Efficacy and safety of vildagliptin, sitagliptin, and linagliptin as add-on therapy in Chinese patients with T2DM inadequately controlled with dual combination of insulin and traditional oral hypoglycemic agent. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2015;7(1):1–9.

Marfella R, Barbieri M, Grella R, Rizzo MR, Nicoletti GF, Paolisso G. Effects of vildagliptin twice daily vs. sitagliptin once daily on 24-hour acute glucose fluctuations. J Diabetes Complications [Internet]. 2010;24(2):79–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2009.01.004.

Shigematsu E, Yamakawa T, Oba MS, Suzuki J, Nagakura J. A randomized controlled trial of vildagliptin versus alogliptin : effective switch from sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(7):567–72.

Nabeno M, Akahoshi F, Kishida H, Miyaguchi I, Tanaka Y, Ishii S, et al. A comparative study of the binding modes of recently launched dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors in the active site. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434(2):191–6.

Kim Y, Kang ES, Jang HC, Kim DJ, Oh T, Kim ES, et al. Teneligliptin versus sitagliptin in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin and glimepiride: a randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(3):631–9.

Tanaka M, Nishimura T, Sekioka R, Itoh H. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor switching as an alternative add-on therapy to current strategies recommended by guidelines: analysis of a retrospective cohort of type 2 diabetic patients. J Diabetes Metab. 2016;7(9):701.

Kim YJ, Park S, Yi W, Yu KS, Kim TH, Oh TJ, et al. Seasonal variation in hemoglobin a1c in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(4):550–5.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the investigators and the participants of the study.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by the Handok Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

HJ.K. and K.W.L. contributed to the design and conduct of the study and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. Y.S.K., C.B.L., M-G.C., H-J.C., S.K.K., J.M.Y., T.H.K., J.H.L., and K.J.A. contributed to the conduct of the study and the interpretation of data. K.K. contributed to the design of the study and analysis of data. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Kyoungmin Kim is an employee of Handok Inc. Hae Jin Kim, Young Sik Kim, Chang Beom Lee, Moon-Gi Choi, Hyuk-Jae Chang, Soo Kyoung Kim, Jae Myung Yu, Tae Ho Kim, Ji Hyun Lee, Kyu Jeung Ahn and Kwan Woo Lee have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent before participating in the study, and the study was initiated after approval of the study protocol by the institutional review board at each site or by the local institutional review boards (Supplementary Table S2), including Ajou University Hospital IRB (AJIRB-MED-OBS-15-410).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8040260.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.J., Kim, Y.S., Lee, C.B. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Switching to Teneligliptin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Inadequately Controlled with Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors: A 12-Week Interim Report. Diabetes Ther 10, 1271–1282 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-0628-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-0628-0