Abstract

Obesity and diabetes incidence rates are increasing dramatically, reaching pandemic proportions. Therefore, there is an urgent need to unravel the mechanisms underlying their pathophysiology. Of particular interest is the close interconnection between gut microbiota dysbiosis and obesity and diabetes progression. Hence, microbiota manipulation through diet has been postulated as a promising therapeutic target. In this regard, secretion of gut microbiota–derived extracellular vesicles is gaining special attention, standing out as key factors that could mediate gut microbiota-host communication. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from gut microbiota and probiotic bacteria allow to encapsulate a wide range of bioactive molecules (such as/or including proteins and nucleic acids) that could travel short and long distances to modulate important biological functions with the overall impact on the host health. EV-derived from specific bacteria induce differential physiological responses. For example, a high-fat diet–induced increase of the proteobacterium Pseudomonas panacis–derived EV is closely associated with the progression of metabolic dysfunction in mice. In contrast, Akkermansia muciniphila EV are linked with the alleviation of high-fat diet–induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Here, we review the newest pieces of evidence concerning the potential role of gut microbiota and probiotic-derived EV on obesity and diabetes onset, progression, and management, through the modulation of inflammation, metabolism, and gut permeability. In addition, we discuss the role of certain dietary patterns on gut microbiota–derived EV profile and the clinical implication that dietary habits could have on metabolic diseases progression through the shaping of gut microbiota–derived EV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gut microbiota is the set of microbes that colonize the gastrointestinal tract of mammals, establishing a mutualistic relationship with the host [115]. Gut microbiota is involved in a wide range of host essential processes, such as digestion and metabolism (i.e., fat storage, indigestible polysaccharide degradation, and therapeutic drug metabolization), development and physiology of the immune system, gut function (i.e., gut permeability regulation and maintenance of gut barrier integrity), angiogenesis, pathogen resistance, bone homeostasis, or behavior [77, 115]. It should be noted that several environmental factors could shape gut microbiota composition, including lifestyle issues, antibiotics, or diet, the latter being considered an important environmental factor that could influence gut microbiota composition [32, 115]. The alteration of gut microbiota homeostasis, commonly known as dysbiosis, has been associated with numerous diseases, such as colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, cardiovascular diseases, neurological disorders, autoimmune diseases, obesity, and diabetes [44, 115].

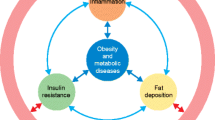

In particular, obesity prevalence is increasing dramatically and it has been estimated that about 57.8% of the world adult population will be overweight or obese by 2030 [29, 66]. Likewise, the global incidence rate of type 2 diabetes, which accounts for 90–95% of all cases of diabetes, is also rising: it has been predicted that it will increase from 6,059 cases per 100,000 in 2017 to 7,079 individuals per 100,000 in 2030 [39, 67]. The association between weight gain and type 2 diabetes risk is well known, by which the term “diabesity” has been coined to those cases when type 2 diabetes is caused by obesity [97, 108]. Obesity and type 2 diabetes are associated with an increased risk to develop a plethora of diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases [22, 54], mental disorders, [10, 12], or cancer [50], and they have also been linked with the severity of infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis or COVID-19 [60, 65].

Recent studies have proposed that gut microbiota dysbiosis could be involved in the onset and progression of obesity and diabetes [32, 112]. Thus, gut microbiota manipulation interventions are postulated as new promising approaches to treat these metabolic disorders, which include dietary interventions (such as administration of prebiotics, probiotics, symbiotics, or low-fat diets), fecal microbiome transplantation, or bariatric surgery [1, 32, 37, 94, 112, 129]. Nevertheless, a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the interaction between gut microbiota and the host is mandatory in order to ultimately identify targets through which the gut microbiota could be effectively manipulated to potentially treat obesity and diabetes.

In recent years, extracellular vesicles (EVs) have emerged as crucial players in inter-kingdom communication, including those established between gut microbiota and mammals [11, 130]. EVs are cell-secreted particles identified in all domains of life (eukaryote, bacteria, and even archaea) that have the potential ability to regulate cell function in an autocrine or paracrine manner [130, 133]. In mammals, depending on their biogenesis and size, EVs have been classified mainly in exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies [43]. Exosomes are EVs of endocytic origin that range in size from 30 to 150 nm [43]. By contrast, microvesicles have a diameter ranging from 100 to 1000 nm and are formed from plasma membrane; and apoptotic bodies range from 50 to 5000 nm and are originated from cells undergoing apoptosis [43]. Plants can also secrete EVs, whose biogenesis, content, and morphology are similar to mammalian exosomes, by which they are usually termed as “exosome-like nanovesicles” [33, 131]. EVs have been also identified in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [80, 114]. Attending to their biogenesis, they have been termed as outer-outer-inner and explosive-outer membrane vesicles in Gram-negative bacteria, and cytoplasmic membrane vesicles in Gram-positive bacteria [122]. As summarized by Cuesta et al. [31], bacterial EVs share many similarities with eukaryotic EVs, including their size (10–400 nm), morphology (spherical particles), and physico-chemical properties (such as stability upon freezing and at 37 °C). However, several differences have been found regarding characteristics such as structure, tolerance to high temperatures, composition, and their biogenesis [31]. Of note, a common characteristic between eukaryotic and bacterial EVs is the ability to transport genetic material, including microRNAs (miRNAs) or miRNA-like molecules, which have been found in a wide range of EVs, such as mammalian exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies [103], plant exosome-like nanovesicles [132], and bacterial EVs [3].

EV cargo is configured by a wide range of bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, polysaccharides, RNA, and DNA [130, 133]. Among the different types of cargo encapsulated in EVs, miRNAs have acquired special notoriety, since it has been reported that they can modulate gene expression in unrelated organisms, including plants-animals, plants-bacteria, and animals-bacteria [78]. Remarkably, true miRNA-like molecules have been identified in bacteria [78]. These molecules are of similar size to eukaryotic miRNAs and can be encapsulated and secreted in EVs, which protect miRNAs from degradation [78]. In particular, gut microbiota-derived EVs have been associated with several host functions, including immune system regulation and cancer suppression and it has also been suggested that these EVs might have a role in gut-brain axis modulation, since it was reported that they could reach the central nervous system and regulate cerebral function [56, 70, 88]. In addition to displaying beneficial effects and their contribution to host homeostasis, the alteration of gut microbiota-derived EV profile has been associated with the progression of several diseases, such as HIV, inflammatory bowel disease, or cancer therapy–induced intestinal mucositis [123]. Furthermore, gut microbiota–derived EVs, in particular those secreted by Paenalcaligenes hominis, could even induce cognitive disorders like Alzheimer’s disease [81].

In this review, we will discuss the potential role of gut microbiota and probiotic-derived EVs on obesity, diabetes, and inflammation, and we will summarize the current pieces of evidence concerning the influence of diet on gut microbiota and probiotic-derived EVs and their potential implications of this interaction on host health.

Role of gut microbiota and probiotic-derived extracellular vesicles on inflammation, obesity, and diabetes

Gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the modulation of host physiological processes whose alterations have been strongly linked to obesity and diabetes onset and progression (i.e., food intake, inflammation, metabolism, and intestinal barrier function) [20, 30, 53, 93]. Growing evidence suggests that gut microbiota–derived EVs could be relevant mediators in microbe-host cross-kingdom communication, playing part in gut microbiota-mediated intestinal homeostasis and ultimately being involved in the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases.

Effects of gut microbiota and probiotic-derived extracellular vesicles on gut barrier fortification and inflammation suppression

Alvarez et al. [5] evidenced that EVs secreted by the probiotic strains of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) and ECOR63 could strengthen intact intestinal epithelial barrier by upregulating zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and claudin-14 expression in vitro and by downregulating the leaky protein claudin-2 in human intestinal epithelial cell culture monolayers. Another study conducted by the same authors [6] showed that EVs isolated from EcN and ECOR63 protected the gut epithelial barrier in human intestinal epithelial cell culture monolayers infected by enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC). Among the effects observed, EcN and ECOR63 EVs prevented tight junction protein redistribution and the protein down-regulation induced by EPEC, resulting in the neutralization of the decrease in intestinal permeability [6]. In this regard, Ashrafian et al. [9] evaluated the effect of EVs isolated from the commensal bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila in the human intestinal epithelial cell culture model Caco-2. Remarkably, the authors observed that A. muciniphila EVs enhanced tight junction gene expression and down-regulated toll-like receptor (TLR) gene expression, which suggested a potential role for A. muciniphila EVs in intestinal barrier permeability and fortification as well as in inflammation reduction [9]. The protective role against inflammatory responses mediated by commensal and/or probiotic bacterial EVs was ratified by the studies of Hiippala et al. [59], which showed that commensal Odoribacter splanchnicus 57 EVs possessed immunomodulatory properties, mitigating the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-8 in enterocyte cultures treated with E. coli-lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The anti-inflammatory properties of O. splanchnicus could potentially rely on sphingolipids, such as sulfobacin B [59]. In addition, Kang et al. [117] also showed that A. muciniphila EVs pre-treatment of a colon epithelial cell line could hinder the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines induced by pathogenic E. coli EVs. The role of gut microbiota and probiotic EVs on modulating intestinal inflammation and gut barrier integrity has been further confirmed by several in vivo studies. For example, Kang et al. [117] provided direct evidence that oral administration of A. muciniphila EVs elicited protective effects, attenuating the severity of colitis-associated phenotype in mice. These effects involved the reduction of weight loss and gut barrier disruption and the control of inflammatory response [117]. In fact, an independent study carried out by Fábrega et al. [46] also described immunomodulatory properties for orally administered probiotic EcN EVs, which protected against the development of experimental-induced colitis in mice by counteracting weight loss, inflammation, and gut barrier damage.

It should be noted that gut microbiota EVs could not only exert immunomodulatory functions through their interaction with gut barrier cells, but they could also communicate with intestinal immune system cells, thus influencing host immunity. In this regard, Bulut et al. [4] determined that EVs derived from the commensal bacterium Pediococcus pentosaceus triggered immuno-suppressive responses both in vitro and in vivo. Using several mouse models of acute inflammation, the authors showed that P. pentosaceus EVs promoted immune tolerance and inhibited inflammation through the direct interaction with bone marrow-derived macrophages and bone marrow progenitors by a TLR-2-dependent mechanism, which stimulates the generation of inflammation regulatory cells (M2-like macrophage and myeloid-derived suppressor-like cells) [4]. The protective effect of gut microbiota EVs against inflammatory disorders was also corroborated by Shen et al. [113], who demonstrated that Bacteroides fragilis EVs prevented colitis development in mice by inducing immune tolerance through activation of dendritic cells [113]. It was also suggested that the immunomodulatory effects of B. fragilis were mediated by a capsular polysaccharide packaged in EVs [113].

Pro-inflammatory effects of gut microbiota– and probiotic-derived extracellular vesicles

Although gut microbiota and probiotic-derived EVs have shown anti-inflammatory effects, other studies have also attributed a pernicious role for some gut microbiota and probiotic EVs in triggering pro-inflammatory responses. For example, Patten et al. [101] demonstrated that EVs derived from the commensal bacterium E. coli C25 could promote pro-inflammatory responses in intestinal epithelial cells in vitro by promoting IL-8 secretion. In addition, Cañas et al. [17] unveiled that EVs derived from the probiotic EcN and the commensal gut microbiota bacterium ECOR12 could enhance the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 in Caco-2 cells, which suggests a role for the EVs of these strains in the modulation of intestinal immune responses. Finally, Fábrega et al. [45] reported that EVs from EcN and ECOR12 could induce immune and defense responses in a human ex vivo model of colonic explants. The authors suggested that outer membrane LPS in EVs could be an explanatory mechanism for the modulation of immune system responses [45]. Among the mechanisms involved, EcN and ECOR12-derived EVs upregulated the chemokine MIP1α, the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10, and the human beta-defensin-2 (HBD-2), an antimicrobial host defense peptide involved in intestinal barrier function [48]. They also enhanced IL-22 production, which has been involved in intestinal barrier protection and its strengthening [45, 86]. It should be highlighted that the induction of moderate inflammatory bowel responses is critical for gut barrier protection [120]. In fact, it has been suggested that gut microbiota–derived EVs with pro-inflammatory properties could be mild enough to be beneficial and contribute to gut barrier integrity and intestinal homeostasis maintenance through the induction of host immune and defense responses [17, 45]. Nevertheless, in a context of dysbiosis or host susceptibility to develop inflammatory disorders, we speculate that an imbalance in the abundance of pro-inflammatory EVs from gut microbiota, a priori to be beneficial to the host, may potentially lead to exacerbated inflammatory responses eventually harmful to the host. In support of this hypothesis, Hickey et al. [58] observed that EVs derived from the commensal Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron could be uptaken by intestinal macrophages and elicit inflammatory response by inducing pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α and IL-1β) production, driving colitis development in genetically susceptible mice.

Direct evidence of the effects of gut microbiota and probiotic-derived extracellular vesicles on obesity and diabetes pathophysiology

Remarkably, recent reports have confirmed the direct connection between modulation of intestinal immune responses and gut barrier integrity to gut microbiota–derived EVs, as well as their link to metabolic function, including improvements of metabolic diseases, such as obesity and diabetes. In this regard, Chelakkot et al. [23] reported a direct relationship between A. muciniphila EVs and the improvement of both gut barrier integrity and metabolic profile in high-fat diet (HFD)–induced diabetic mice. Thereby, oral administration of A. muciniphila EVs to HFD-fed mice decreased gut barrier permeability, reduced body weight gain, and improved glucose tolerance [23]. In addition, administration of A. muciniphila EVs to LPS-treated Caco-2 cells decreased intestinal permeability and improved intestinal barrier integrity through the up-regulation of occludin expression [23]. These findings led the authors to propose that A. muciniphila EVs could be a therapeutic tool to treat metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes [23]. This hypothesis was confirmed by Ashrafian et al. [8] who demonstrated an effect of A. muciniphila EVs on the alleviation of obesity in mice. A. muciniphila EVs reduced food intake, body weight, and adiposity; increased gut barrier integrity; ameliorated intestinal and adipose tissue inflammation; and improved metabolic function in HFD-induced obese mice [8]. Indeed, it could be suggested that the improvements on host metabolic health due to A. muciniphila [35] and other gut microbiota species might be mediated, at least partially, through dynamic EV production.

In contrast, Choi et al. [25] revealed the implication of gut microbiota–derived EVs in the worsening of diet-induced metabolic disorders, in the context of gut microbiota dysbiosis. After investigating the effect of stool EVs isolated from HFD-fed mice, the authors observed that these EVs could blunt glucose metabolism by promoting insulin resistance in both skeletal muscle and adipose tissue [25]. This study demonstrated that Pseudomonas panacis LPS-containing EVs were more abundant in HFD-fed mice and they mediated the detrimental effect of the HFD on glucose metabolism [25]. Remarkably, the alteration of gut microbiota EV profile was more severe than changes in gut microbe composition and, unlike gut microbes, gut microbiota EVs could penetrate into the bloodstream and arrive to insulin-sensitive tissues [25]. This result suggested that HFD-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis could be accompanied by changes in gut microbiota EV profile that could have detrimental effects on energy homeostasis, and thus contribute to the onset and progression of metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes. Notably, the remarkable role of commensal bacteria-derived EVs on host physiology and their contribution to the pathogenesis of dysbiosis-related diseases have been also elucidated by the studies of Yang et al. [134] in the lung commensal microbiota. In a mouse model of experimental lung fibrosis, the alteration of lung microbiota promoted IL-17B production, contributing to the pathogenesis of the disease, and such effect was mediated by EVs secreted by commensal bacteria of the genera Bacteroides and Prevotella, whose abundance was up-regulated in this pathophysiological context [134].

Some pieces of evidence dealing with the potential effect of gut microbiota and probiotic bacteria–derived EVs on host physiology (including shaping of energy metabolism, immune responses, and gut barrier function) are summarized in Table 1.

Characterization of gut microbiota and probiotic-derived extracellular vesicle cargo

The characterization of gut microbiota and probiotic-derived EV cargo has been mainly focused on the analysis of the proteome and occasionally also the lipidome and the genomic DNA [4, 14, 16, 23, 25, 45, 59, 75, 98, 113]. Of note, as previously described, the effector molecules responsible for the effect of probiotic- and gut microbiota-derived EVs have been identified [25, 45, 113]. However, the identification of bioactive molecules that mediate gut microbiota and probiotic-derived EVs is in its infancy, since most of the studies have been focused on the characterization of properties, effects, and cargo of pathogenic bacteria–derived EVs rather than commensal bacteria-derived EVs. Furthermore, as reviewed by other authors, it should be noted that bacteria-derived EVs are also enriched in numerous molecules besides proteins, like glycolipids, lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycans, and nucleic acids (i.e., DNA and several types of RNA, such as rRNAs, tRNAs, mRNAs, and miRNAs-like molecules) [36, 130]. For this reason, a more exhaustive characterization of the different types of cargo of gut microbiota– and probiotic-derived EVs is required, since it cannot be ruled out that other bioactive molecules such as miRNAs could potentially be responsible for some of the effects of these EVs on the host.

However, there are currently limitations to characterize gut microbiota-derived EVs, which make the identification of the molecules involved in their physiological effects difficult. Several methods have been carried out to isolate and characterize bacterial EVs from in vitro cultures [55, 98]. However, the isolation and characterization of the heterogeneous profile of the gut microbiota are far more complex. As it was pointed out by other authors [95], a major obstacle is the lack of bacterial EV universal markers and their size-similarities to mammalian EVs, which complicate their separation from mammalian EVs in corporal fluids. Nevertheless, research continues to overcome these limitations, and recently Lagos et al. [75] isolated and characterized EVs from pig gut microbiota in vitro, and new methods have been developed to isolate more effectively bacterial EVs from body fluids [124]. Other authors also identified the bacterial origin of fecal EVs through the amplification of the DNA from the most common gut microbiota phyla by PCR [64]. However, exhaustive identification of the origin of fluids and fecal-derived EVs and EV-derived molecules, such as miRNAs, is still a challenge due to the complexity of the material.

Biological effect of miRNA contained within bacterial extracellular vesicles

It has been unveiled that bacterial EV-derived miRNAs could exert trans-kingdom gene expression regulation and influence host biological functions. For example, Choi et al. [27] identified miRNA-size small RNAs in periodontal pathogen EVs that could downregulate cytokine expression (IL-5, IL-13, and IL-15) in Jurkat T cells and predicted human immune-related target genes, suggesting a potential role in shaping host immune system responses. Han et al. [57] expanded knowledge on periodontal pathogen EVs and revealed that miRNA-like molecules of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans EVs could enter human macrophages and regulate gene expression, promoting TNF-α production. It was also observed that A. actinomycetemcomitans EVs reached the brain in mice and the exogenous RNA cargo up-regulated TNF-α expression, which led to propose a potential role in neuroinflammatory disorders [57]. Thus, it should be explored if, like pathogenic bacteria–derived EVs, gut microbiota EVs could carry small RNAs, including miRNAs, that may be involved in the crosstalk between gut microbiota and the host, as some authors have already hypothesized [11, 21, 26, 57].

In fact, the reciprocal interaction, host-gut microbiota mediated by host EV-derived miRNAs, has been also documented. Indeed, the effects of host EV-derived miRNAs on gut microbiota-gene expression regulation were described by Liu et al. [85]. This pioneering study revealed that gut epithelial cells and homeodomain-only protein homeobox (HOPX)–positive cells can secrete fecal miRNAs and influence gut microbiota gene expression, controlling gut microbiota composition and homeostasis [85]. In turn, several studies have shown that gut microbiota can affect host-miRNA expression and modulate crucial host functions, such as gut permeability, inflammation, or metabolism [34, 96, 125, 127]. A correlation between gut microbiota–induced alterations on host-miRNA profile and obesity and type 2 diabetes has been also documented in several studies [49, 83, 126]. In addition, probiotic administration has also been reported to influence host miRNA expression [105]. Thus, indirectly, it has been shown that gut microbiota and probiotics could regulate host gene expression through their influence on host-miRNA expression. However, the direct interaction on host gene expression mediated by miRNA-like molecules derived from gut microbiota and/or probiotics EVs must be proven and clarified in future experiments.

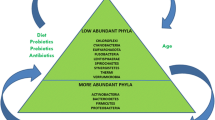

Role of diet on the modulation of gut microbiota–derived extracellular vesicles and the potential consequences on metabolic disorder outcomes

Compelling pieces of evidence indicate that diet exerts a powerful influence on the composition, abundance, diversity, and metabolism of gut microbiota and it could promote gut microbiota changes linked to the prevention and/or treatment as well as the development and/or progression of metabolic disorders [72, 79]. In fact, it has been observed that dietary patterns influence gut microbiota populations differentially, favoring or inhibiting certain bacterial species [72, 104]. Therefore, promotion of a specific gut microbiota composition profile has been established for a wide range of diets, such as vegan/vegetarian diet, gluten-free diet, Western diet, or Mediterranean diet, which have an impact on metabolism and gut barrier and immune functions [2, 51, 110, 135]. A more thorough description of this issue has been summarized in other reviews [72, 104]. For instance, the Western diet may promote obesity development by switching gut microbiota profile towards a decrease of beneficial/protective bacteria, reducing gut microbiota diversity, and enhancing local (gut) inflammation [2, 7, 41]. By contrast, a vegetarian diet has been associated with obesity prevention in several studies, for example, by increasing the abundance of commensal beneficial bacteria (Bacteroides, Prevotella, Clostridium sp.) and/or decreasing diversity and inflammation-related bacteria (Enterobacteriaceae) [68, 89]. Also, strong adherence to the Mediterranean diet has been reported to increase the population of some beneficial bacteria, shifting microbiota status towards a healthier pattern [107]. Therefore, gut microbiota shaping through dietary interventions could be an attractive, effective, and non-invasive strategy to prevent and/or treat obesity and diabetes.

However, given the growing evidence supporting an important role for gut microbiota-derived EVs in gut microbiota-host communication, and their influence in physiological function whose disturbance has been associated with metabolic disorders (i.e., inflammation, gut permeability, or metabolism) (see the “Role of gut microbiota and probiotic-derived extracellular vesicles on inflammation, obesity, and diabetes” section), it would be worthy to explore the following hypothesis:

-

1.

The impact of diet on gut microbiota–derived EV profile.

-

2.

If the potential modulation of gut microbiota–derived EV profile through diet could have an impact on host physiology and contribute to the development (or treatment) of metabolic disorders.

Some of these issues are just starting to be explored and an intriguing role for diet in shaping gut microbiota-derived EV characteristics, such as their production, cargo, and composition, is emerging. Remarkably, Tan et al. [118] presented evidence supporting the influence of diet on gut microbiota EV production. These authors showed that the administration of a high-protein diet (HPD) enhanced EV production in non-dysbiotic mice, activating the gut epithelial TLR4-signaling pathway [118]. Activation of the TLR4 pathway, in turn, increased immune regulators of IgA production (in particular CCL28) that modulated host-gene expression towards an enhancement of IgA production [118]. Notably, the authors attributed the gut microbiota–derived EV production enhancement to the HPD-induced upregulation of succinate [118]. Of note, IgA controls bacteria-host interactions and is implicated in the maintenance of gut homeostasis by, for instance, restricting spatially pathogens and pathogenic microbiota, affecting bacterial viability, and modulating pathogenicity [84, 99]. Indeed, Luck et al. [87] observed that HFD decreased IgA production in mice and attributed a functional role for IgA on glucose homeostasis maintenance, gut and adipose tissue inflammation, gut permeability, microbiota encroachment, and microbiota composition, which suggested an implication for IgA downregulation in HFD-induced metabolic diseases. In accordance, Tan et al. [118] also determined that HFD did not induce upregulation of succinate production and that gut microbiota-derived EVs from HFD-fed mice inhibited immune regulators of IgA production, in particular the cytokine APRIL (A Proliferation-Inducing Ligand), dramatically decreasing IgA levels. In this line, some studies have revealed that succinic acid or succinate treatments could alleviate obesity in mice [62, 128] and, as reviewed by other authors, succinate production by gut microbiota might have beneficial effects on metabolic disorders [47].

Furthermore, Lagos et al. [75] characterized the profile of EVs derived from porcine stool samples, determining that the secretion of Clostridiales, Bacilli, and Enterobacteriales EVs increased in response to the administration of the carbohydrate β-mannan. Indeed, β-mannan administration not only stimulated gut microbiota EV production but also modified their protein cargo [75]. However, such EVs did not carry polysaccharide- or mannan-degrading enzymes, so the relationship between β-mannan and EV production remains undermined [75]. Deep research regarding the identification of specific bacterial species whose EV production increased after β-mannan treatment, could help to elucidate the effect of β-mannan-gut microbiota EV modulation on host health.

The impact of diet on the progression of metabolic disorders through shaping gut microbiota–derived EVs characteristic has been partially revealed by Choi et al. [25]. These authors reported that administration of a HFD to mice altered the amount, size, and global content of gut microbiota EVs [25]. Thus, the characterization of EVs of HFD-fed mice stools showed a size decrease of EVs and changes in the global protein content profile, marked by an increase in LPS, due to the enhancement of EVs derived from LPS-expressing Proteobacteria [25]. In this context, other studies have observed that LPS (eventually present in bacteria-derived EVs) could increase in response to a HFD and have identified LPS as a key triggering factor in diabetes and obesity onset [19]. LPS might increase metabolic endotoxemia, which in turn could disrupt energy homeostasis, promote inflammation, induce insulin resistance and diabetes, and enhance body weight gain in mice [19]. Thus, the enhancement of LPS-containing gut microbiota EVs could potentially be an important underlying mechanism that could orchestrate the promotion of metabolic endotoxemia and metabolic disorders induced by HFD. In this sense, it has been reported that blood levels of LPS-containing EVs are higher in patients with intestinal barrier dysfunction; and these EVs strongly stimulated secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [123]. On the other hand, gut barrier permeability may be compromised in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes and dietary lipids could aggravate permeability disturbance [52]. Therefore, it would be necessary to confirm in humans (1) if gut barrier disruption could enhance the translocation of LPS-positive bacterial EVs, (2) if a Western diet could enhance the production of these EVs, and (3) further clarify the implication of EVs from LPS-positive bacteria in human metabolic disorders, as it was previously described in mice.

Interestingly, Müller et al. [92] also showed that probiotic-Lactobacilli EV properties could be shaped by their living microenvironment. It was found that culture conditions, agitation, and pH 5, respectively, modified Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus plantarum EV protein content and strengthened their anti-inflammatory properties, leading to the enhancement of IL-10 and TNF-α production after macrophage treatment in vitro [92]. In this context, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that EVs derived from bacteria commonly used as probiotics possess anti-inflammatory properties and could be potentially used to prevent or treat inflammatory disorders [28, 38, 71]. For instance, it has been described that Lactobacillus paracasei EVs counteracted LPS-induced human colorectal cell inflammation in vitro and attenuated inflammation responses and ameliorated colitis in mice, suggesting an important role in gut homeostasis maintenance [28]. In addition, oral administration of EVs derived from A. muciniphila displayed immunomodulatory properties and ameliorated HFD-induced obesity in mice [8]. On the other hand, several dietary ingredients beneficially affect the growth, survival, and/or activity of probiotic bacteria [42, 111]. This finding provides a new avenue to analyze if specific food ingredients, in a similar manner as culture conditions, could enhance probiotic EV immunomodulatory properties and if these EVs with strengthened anti-inflammatory effects could be used to effectively treat metabolic diseases, in which inflammation is a hallmark [61].

Effect of diet on gut microbiota through food-derived extracellular vesicles

It is worthy of note that a substantial amount of studies have shown that dietary EVs can directly interact with mammalian cells, such as tumor cells, epithelial cells, immune system cells, or hepatocytes, and they could elicit biological functions that could have an impact on host health, even emerging as potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of a wide range of diseases, such as inflammatory disorders, cancer or steatosis [102, 106]. In addition, dietary EVs could be also prominent players in the interaction between diet and gut microbiota, which suggests that dietary EVs might be implicated in the extensively described effect of diet on host physiology. In support of this notion, it has been reported that dietary bovine milk exosomes (a particular type of EV) could modulate gut microbiota composition, which was associated with the increase of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) levels [121]. In addition, the authors identified the consequences of exosome-induced gut microbiota modulation in mice, suggesting an effect on the maintenance of intestinal barrier function and intestinal immune system regulation [121]. Notably, results provided by other studies have revealed that gut microbiota SCFAs could be useful in the improvement of obesity and diabetes [18, 82], but a direct connection between the modulation of SCFA production by dietary EVs and metabolic counteraction remains to be established. However, the direct effect of bovine milk exosomes on human health is unclear, since it has been also suggested that they could contribute to the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes [90]. This might be due to the fact that several of the most abundant miRNAs of bovine milk–derived exosomes could disrupt energy homeostasis, influencing processes such as adipogenesis, insulin secretion, or glucose transporters [90]. In addition, it has been shown that dietary plant–derived EVs could also shape gut microbiota and accumulated evidence suggests that exogenous miRNAs (xenomiRs from foods) within EVs could influence human health, particularly involving gut microbiota and intestinal barrier function [40]. Recently, Teng et al. [119] observed that ginger exosome-like nanoparticles, through miRNAs, could regulate Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LGG) gene expression, influencing the intestinal immune system and improving gut barrier integrity, ameliorating colitis in mice [119]. It has been reported that LGG administration has anti-obesity and anti-diabetic properties, being able to alter gut microbiota composition, decrease weight gain, inhibit leptin resistance, enhance glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, and reduce adiposity [24, 63, 69, 100]. Thus, manipulation of gut commensal LGG through dietary ginger exosome–like nanoparticles containing miRNAs may be a promising strategy to treat metabolic syndrome. Remarkably, Berger et al. [13] provided direct evidence of the functional consequences of plant-derived EVs in obesity and predicted potential EV-encapsulated miRNAs that might be involved in the observed effects, but it has not been explored whether these EVs could also target gut microbiota [13].

Conclusions and future directions

The use of probiotics to treat metabolic disorders in order to enhance weight loss and to improve host homeostasis has been an interesting strategy to achieve optimal metabolic health reviewed by several authors [76, 109]. Alternatively, there is compelling evidence regarding the emergence of probiotic- and gut microbiota–derived EVs as a potentially safe and effective alternative as compared to probiotics, as discussed in recent reviews [91]. In line with these findings, in 2013, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved the bacterial-derived 4CMenB vaccine, which is a bacteria extracellular vesicle–based vaccine against meningococcal infection for children [15]. Indeed, several authors hypothesized that, considering the efficacy and safety of this vaccine, likewise, bacterium-derived EVs could be potentially used as drugs and could be administered to modulate host physiology and to treat inflammatory diseases [4]. The potential of a new formulation based on probiotic EVs, called probiomimetics, as a therapeutic tool to treat inflammatory diseases, has been already shown [74]. The probiomimetics are engineered therapeutic agents that consist of microvesicles with surface-attached probiotic EVs [74]. Nevertheless, further research is needed to clarify whether the observed effects of probiotics on improving diet-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis [73, 116] could be mediated by their EVs, and whether the administration of gut microbiota and probiotic EVs could be used as an emerging tool for the prevention and management of metabolic diseases, since the available evidence in this field is limited. In addition, exhaustive characterization of the cargo of probiotic- and gut microbiota–derived EVs is still required to identify all the bioactive molecules (i.e., miRNAs) responsible for their biological effects.

On the other hand, some questions that are poorly understood regarding the effects of diet on shaping gut microbiota EVs should be elucidated, which include the following:

-

1.

To determine to which extent the contribution of diet-induced microbiota dysbiosis to obesity and diabetes pathogenesis is mediated by the alteration of the microbiota EV profile.

-

2.

To identify dietary patterns that could potentially lead to the establishment of a healthy (i.e., Mediterranean or vegetarian diets) or detrimental (i.e., Western or HFD) gut EV profile.

-

3.

To favorably modulate the gut microbiota EV profile through the administration of certain bacterial EVs, probiomimetics, bioactive compounds, or foods that could represent new approaches to tackle metabolic diseases.

Improving the knowledge of the mechanisms underlying the crosstalk between diet, gut microbiota, and the host would allow the identification of new therapeutic targets for obesity and diabetes prevention and management. As presented in Fig. 1, gut microbiota–, probiotic-, and food-derived EVs could be a key factor of this interaction. Administration of probiotic- and commensal bacteria-derived EVs and/or manipulation of gut microbiota-derived EVs through dietary interventions should be explored as potential strategies to prevent and treat metabolic disorders.

Schematic model of the hypothetical impact of dietary patterns on gut microbiota extracellular vesicle profile, and the effect of probiotic- and gut microbiota–derived extracellular vesicles on metabolic syndrome onset and/or progression. A mechanism by which unhealthy dietary patterns could contribute to obesity and/or diabetes progression could be the promotion of gut microbiota dysbiosis and the enhancement of detrimental gut microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles amount. In turn, these extracellular vesicles could potentially impair gut barrier permeability and intestinal inflammation, and could be distributed to peripheral organs through systemic circulation, impairing metabolism and promoting inflammation, and subsequently aggravating the severity of metabolic disorders. Enhancement of beneficial gut microbiota extracellular vesicles through plants and plant-derived extracellular vesicles from healthy dietary patterns and/or the administration of formulations based of probiotic- and gut microbiota–derived extracellular vesicles could potentially be a strategy to treat metabolic disorders by counteracting dysbiosis, gut permeability increase, inflammation, metabolic homeostasis disturbances, and nervous-system derangements. Formulations based on bacterial extracellular vesicles could be optimized in order to increase their properties and effects by designing efficient therapeutic agents (i.e., probiomimetics, which are bacterial derived extracellular vesicles coupled to microvesicles), establishing optimal cell culture conditions or administrating certain food-ingredients. All the hypotheses presented in this model must be further confirmed; especially the ones marked with dashed arrows should be proven. Brain template from BioRender (https://biorender.com)

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Change history

23 February 2022

Springer Nature’s version of this paper was updated to reflect the Funding information: Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

References

Adeshirlarijaney A, Gewirtz AT (2020) Considering gut microbiota in treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Gut Microbes 11:253–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2020.1717719

Agus A, Denizot J, Thévenot J et al (2016) Western diet induces a shift in microbiota composition enhancing susceptibility to adherent invasive E coli infection and intestinal inflammation. Sci Rep 6:19032. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19032

Ahmadi Badi S, Bruno SP, Moshiri A et al (2020) Small RNAs in outer membrane vesicles and their function in host-microbe interactions. Front Microbiol 11:1209. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01209

Alpdundar Bulut E, Bayyurt Kocabas B, Yazar V et al (2020) Human gut commensal membrane vesicles modulate inflammation by generating M2-like macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol 205:2707–2718. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.2000731

Alvarez CS, Badia J, Bosch M et al (2016) Outer membrane vesicles and soluble factors released by probiotic escherichia coli nissle 1917 and commensal ECOR63 enhance barrier function by regulating expression of tight junction proteins in intestinal epithelial cells. Front Microbiol 7:1981. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01981

Alvarez CS, Giménez R, Cañas MA et al (2019) Extracellular vesicles and soluble factors secreted by Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 and ECOR63 protect against enteropathogenic E coli induced intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction. BMC Microbiol 19:166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1534-3

Amato KR, Yeoman CJ, Cerda G et al (2015) Variable responses of human and non-human primate gut microbiomes to a Western diet. Microbiome 3:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-015-0120-7

Ashrafian F, Shahriary A, Behrouzi A et al (2019) Akkermansia muciniphila-derived extracellular vesicles as a mucosal delivery vector for amelioration of obesity in mice. Front Microbiol 10:2155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02155

Ashrafian F, Behrouzi A, Shahriary A et al (2019) Comparative study of effect of Akkermansia muciniphila and its extracellular vesicles on toll like receptors and tight junction. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 12:163–168. https://doi.org/10.22037/ghfbb.v12i2.1537

Avila C, Holloway AC, Hahn MK et al (2015) An overview of links between obesity and mental health. Curr Obes Rep 4:303–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-015-0164-9

Badi SA, Moshiri A, Fateh A et al (2017) Microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles as new systemic regulators. Front Microbiol 8:1610

Balhara YP (2011) Diabetes and psychiatric disorders. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 15:274–283. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.85579

Berger E, Colosetti P, Jalabert A et al (2020) Use of nanovesicles from orange juice to reverse diet-induced gut modifications in diet-induced obese mice. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 18:880–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2020.08.009

Bhar S, Edelmann MJ, Jones MK (2021) Characterization and proteomic analysis of outer membrane vesicles from a commensal microbe. Enterobacter cloacae J Proteomics 231:103994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2020.103994

Bryan P, Seabroke S, Wong J et al (2018) Safety of multicomponent meningococcal group B vaccine (4CMenB) in routine infant immunisation in the UK: a prospective surveillance study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2:395–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30103-2

Bryant WA, Stentz R, Le GG et al (2017) In Silico analysis of the small molecule content of outer membrane vesicles produced by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron indicates an extensive metabolic link between microbe and host. Front Microbiol 8:2440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02440

Cañas MA, Fábrega MJ, Giménez R et al (2018) Outer membrane vesicles from probiotic and commensal escherichia coli activate NOD1-mediated immune responses in intestinal epithelial cells. Front Microbiol 9:498. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00498

Canfora EE, Jocken JW, Blaak EE (2015) Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11:577–591. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2015.128

Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA et al (2007) Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 56:1761–1772. https://doi.org/10.2337/db06-1491

Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C et al (2008) Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57:1470–1481. https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-1403

Celluzzi A, Masotti A (2016) How our other genome controls our epi-genome. Trends Microbiol 24:777–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2016.05.005

Cercato C, Fonseca FA (2019) Cardiovascular risk and obesity. Diabetol Metab Syndr 11:74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-019-0468-0

Chelakkot C, Choi Y, Kim DK et al (2018) Akkermansia muciniphila-derived extracellular vesicles influence gut permeability through the regulation of tight junctions. Exp Mol Med 50:e450. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.282

Cheng YC, Liu JR (2020) Effect of lactobacillus rhamnosus gg on energy metabolism, leptin resistance, and gut microbiota in mice with diet-induced obesity. Nutrients 12:2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092557

Choi Y, Kwon Y, Kim DK et al (2015) Gut microbe-derived extracellular vesicles induce insulin resistance, thereby impairing glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle. Sci Rep 5:15878. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15878

Choi JW, Um JH, Cho JH, Lee HJ (2017) Tiny RNAs and their voyage via extracellular vesicles: Secretion of bacterial small RNA and eukaryotic microRNA. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 242:1475–1481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370217723166

Choi JW, Kim SC, Hong SH, Lee HJ (2017) Secretable small RNAs via outer membrane vesicles in periodontal pathogens. J Dent Res 96:458–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034516685071

Choi JH, Moon CM, Shin TS et al (2020) Lactobacillus paracasei-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate the intestinal inflammatory response by augmenting the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Exp Mol Med 52:423–437. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-019-0359-3

Chooi YC, Ding C, Magkos F (2019) The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism 92:6–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2018.09.005

Cornejo-Pareja I, Muñoz-Garach A, Clemente-Postigo M, Tinahones FJ (2019) Importance of gut microbiota in obesity. Eur J Clin Nutr 72:26–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0306-8

Cuesta CM, Guerri C, Ureña J, Pascual M (2021) Role of microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles in gut-brain communication. Int J Mol Sci 22:4235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22084235

Cuevas-Sierra A, Ramos-Lopez O, Riezu-Boj JI et al (2019) Diet, gut microbiota, and obesity: links with host genetics and epigenetics and potential applications. Adv Nutr 10:S17–S30. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy078

Cui Y, Gao J, He Y, Jiang L (2020) Plant extracellular vesicles. Protoplasma 257:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-019-01435-6

Dalmasso G, Nguyen HTT, Yan Y et al (2011) Microbiota modulate host gene expression via microRNAs. PLoS ONE 6:e19293. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019293

Dao MC, Everard A, Aron-Wisnewsky J et al (2016) Akkermansia muciniphila and improved metabolic health during a dietary intervention in obesity: relationship with gut microbiome richness and ecology. Gut 65:426–436. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308778

Dauros-Singorenko P, Blenkiron C, Phillips A, Swift S (2018) The functional RNA cargo of bacterial membrane vesicles. FEMS Microbiol Lett 365. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fny023

Davis CD (2016) The gut microbiome and its role in obesity. Nutr Today 51:167–174. https://doi.org/10.1097/NT.0000000000000167

de RodovalhoRodovalho V, da Silva RosaLuz B, Rabah H et al (2020) Extracellular vesicles produced by the probiotic propionibacterium freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129 mitigate inflammation by modulating the NF-κB pathway. Front Microbiol 11:1544. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01544

Deshpande AD, Harris-Hayes M, Schootman M (2008) Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetes-related complications. Phys Ther 88:1254–1264. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20080020

Díez-Sainz E, Lorente-Cebrián S, Aranaz P et al (2021) Potential mechanisms linking food-derived MicroRNAs, gut microbiota and intestinal barrier functions in the context of nutrition and human health. Front Nutr 8:586564. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.586564

Ding S, Chi MM, Scull BP et al (2010) High-fat diet: bacteria interactions promote intestinal inflammation which precedes and correlates with obesity and insulin resistance in mouse. PLoS ONE 5:e12191. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012191

Do Espírito Santo AP, Perego P, Converti A, Oliveira MN (2011) Influence of food matrices on probiotic viability - a review focusing on the fruity bases. Trends Food Sci Technol 22:377–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2011.04.008

Doyle LM, Wang MZ (2019) Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 8:727. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8070727

Durack J, Lynch SV (2019) The gut microbiome: relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy. J Exp Med 216:20–40. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20180448

Fábrega MJ, Aguilera L, Giménez R et al (2016) Activation of immune and defense responses in the intestinal mucosa by outer membrane vesicles of commensal and probiotic Escherichia coli strains. Front Microbiol 7:705. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00705

Fábrega MJ, Rodríguez-Nogales A, Garrido-Mesa J et al (2017) Intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of outer membrane vesicles from Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 in DSS-experimental colitis in mice. Front Microbiol 8:1274. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01274

Fernández-Veledo S, Vendrell J (2019) Gut microbiota-derived succinate: friend or foe in human metabolic diseases? Rev Endocr Metab Disord 20:439–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-019-09513-z

Fusco A, Savio V, Cammarota M et al (2017) Beta-defensin-2 and beta-defensin-3 reduce intestinal damage caused by salmonella typhimurium modulating the expression of cytokines and enhancing the probiotic activity of enterococcus faecium. J Immunol Res 2017:6976935. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6976935

Gaddam RR, Jacobsen VP, Kim YR et al (2020) Microbiota-governed microRNA-204 impairs endothelial function and blood pressure decline during inactivity in db/db mice. Sci Rep 10:10065. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66786-0

Gallagher EJ, LeRoith D (2015) Obesity and diabetes: the increased risk of cancer and cancer-related mortality. Physiol Rev 95:727–748. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00030.2014

Garcia-Mantrana I, Selma-Royo M, Alcantara C, Collado MC (2018) Shifts on gut microbiota associated to Mediterranean diet adherence and specific dietary intakes on general adult population. Front Microbiol 9:890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00890

Genser L, Aguanno D, Soula HA et al (2018) Increased jejunal permeability in human obesity is revealed by a lipid challenge and is linked to inflammation and type 2 diabetes. J Pathol 246:217–230. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.5134

Gérard P (2016) Gut microbiota and obesity. Cell Mol Life Sci 73:147–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-015-2061-5

Glovaci D, Fan W, Wong ND (2019) Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 21:21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-019-1107-y

Grande R, Celia C, Mincione G et al (2017) Detection and physicochemical characterization of membrane vesicles (MVs) of Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938. Front Microbiol 8:1040. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01040

Haas-neill S, Forsythe P (2020) A budding relationship: bacterial extracellular vesicles in the microbiota–Gut–brain axis. Int J Mol Sci 21:8899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21238899

Han EC, Choi SY, Lee Y et al (2019) Extracellular RNAs in periodontopathogenic outer membrane vesicles promote TNF-α production in human macrophages and cross the blood-brain barrier in mice. FASEB J 33:13412–13422. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201901575R

Hickey CA, Kuhn KA, Donermeyer DL et al (2015) Colitogenic Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron antigens access host immune cells in a sulfatase-dependent manner via outer membrane vesicles. Cell Host Microbe 17:672–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.002

Hiippala K, Barreto G, Burrello C et al (2020) Novel odoribacter splanchnicus strain and its outer membrane vesicles exert immunoregulatory effects in vitro. Front Microbiol 11:575455. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.575455

Holly JMP, Biernacka K, Maskell N, Perks CM (2020) Obesity, diabetes and COVID-19: an infectious disease spreading from the east collides with the consequences of an unhealthy Western lifestyle. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 11:582870. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.582870

Hotamisligil GS (2006) Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444:860–867. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05485

Ives SJ, Zaleski KS, Slocum C et al (2020) The effect of succinic acid on the metabolic profile in high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Physiol Rep 8:e14630. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.14630

Ji Y, Park S, Park H et al (2018) Modulation of active gut microbiota by Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in a diet induced obesity murine model. Front Microbiol 9:710. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00710

Kameli N, Borman R, Lpez-Iglesias C et al (2021) Characterization of feces-derived bacterial membrane vesicles and the impact of their origin on the inflammatory response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11:667987. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.667987

Karlsson EA, Beck MA (2010) The burden of obesity on infectious disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 235:1412–1424. https://doi.org/10.1258/ebm.2010.010227

Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS et al (2008) Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes (Lond) 32:1431–1437. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.102

Khan MAB, Hashim MJ, King JK et al (2020) Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes - global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J Epidemiol Glob Health 10:107–111. https://doi.org/10.2991/JEGH.K.191028.001

Kim M-S, Hwang S-S, Park E-J, Bae J-W (2013) Strict vegetarian diet improves the risk factors associated with metabolic diseases by modulating gut microbiota and reducing intestinal inflammation. Environ Microbiol Rep 5:765–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12079

Kim SW, Park KY, Kim B et al (2013) Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG improves insulin sensitivity and reduces adiposity in high-fat diet-fed mice through enhancement of adiponectin production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 431:258–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.121

Kim OY, Park HT, Dinh NTH et al (2017) Bacterial outer membrane vesicles suppress tumor by interferon-γ-mediated antitumor response. Nat Commun 8:626. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00729-8

Kim MH, Choi SJ, Il CH et al (2018) Lactobacillus plantarum-derived extracellular vesicles protect atopic dermatitis induced by Staphylococcus aureus-derived extracellular vesicles. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 10:516–532. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2018.10.5.516

Kim B, Choi H-N, Yim J-E (2019) Effect of Diet on the gut microbiota associated with obesity. J Obes Metab Syndr 28:216–224. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes.2019.28.4.216

Kong C, Gao R, Yan X et al (2019) Probiotics improve gut microbiota dysbiosis in obese mice fed a high-fat or high-sucrose diet. Nutrition 60:175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2018.10.002

Kuhn T, Koch M, Fuhrmann G (2020) Probiomimetics—novel lactobacillus-mimicking microparticles show anti-inflammatory and barrier-protecting effects in gastrointestinal models. Small 16:e2003158. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202003158

Lagos L, La Rosa SL, Arntzen M et al (2020) Isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles secreted in vitro by porcine microbiota. Microorganisms 8:983. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8070983

Lau E, Neves JS, Ferreira-Magalhães M et al (2019) Probiotic ingestion, obesity, and metabolic-related disorders: results from NHANES, 1999–2014. Nutrients 11:1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071482

Laukens D, Brinkman BM, Raes J et al (2016) Heterogeneity of the gut microbiome in mice: Guidelines for optimizing experimental design. FEMS Microbiol Rev 40:117–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuv036

Layton E, Fairhurst AM, Griffiths-Jones S et al (2020) Regulatory RNAs: a universal language for inter-domain communication. Int J Mol Sci 21:8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21238919

Lazar V, Ditu LM, Pircalabioru GG et al (2019) Gut microbiota, host organism, and diet trialogue in diabetes and obesity. Front Nutr 6:21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2019.00021

Lee E-Y, Choi D-Y, Kim D-K et al (2009) Gram-positive bacteria produce membrane vesicles: proteomics-based characterization of Staphylococcus aureus-derived membrane vesicles. Proteomics 9:5425–5436. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.200900338

Lee K-E, Kim J-K, Han S-K et al (2020) The extracellular vesicle of gut microbial Paenalcaligenes hominis is a risk factor for vagus nerve-mediated cognitive impairment. Microbiome 8:107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00881-2

Li X, Shimizu Y, Kimura I (2017) Gut microbial metabolite short chain fatty acids and obesity. Biosci Microbiota Food Heal 36:135–140. https://doi.org/10.12938/bmfh.17-010

Li L, Li C, Lv M et al (2020) Correlation between alterations of gut microbiota and miR-122-5p expression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Transl Med 8:1481. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-6717

Li Y, Jin L, Chen T, Pirozzi CJ (2020) The effects of secretory IgA in the mucosal immune system. Biomed Res Int 2020:2032057. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2032057

Liu S, Da Cunha AP, Rezende RM et al (2016) The host shapes the gut microbiota via fecal microRNA. Cell Host Microbe 19:32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.005

Lo BC, Shin SB, Canals Hernaez D et al (2019) IL-22 preserves gut epithelial integrity and promotes disease remission during chronic Salmonella infection. J Immunol 202:956–965. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1801308

Luck H, Khan S, Kim JH et al (2019) Gut-associated IgA+ immune cells regulate obesity-related insulin resistance. Nat Commun 10:3650. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11370-y

Macia L, Nanan R, Hosseini-Beheshti E, Grau GE (2020) Host-and microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles, immune function, and disease development. Int J Mol Sci 21:107. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010107

Matijašić BB, Obermajer T, Lipoglavšek L et al (2014) Association of dietary type with fecal microbiota in vegetarians and omnivores in Slovenia. Eur J Nutr 53:1051–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-013-0607-6

Melnik BC, Schmitz G (2019) Exosomes of pasteurized milk: potential pathogens of Western diseases. J Transl Med 17:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-018-1760-8

Molina-Tijeras JA, Gálvez J, Rodríguez-Cabezas ME (2019) The immunomodulatory properties of extracellular vesicles derived from probiotics: a novel approach for the management of gastrointestinal diseases. Nutrients 11:1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11051038

Müller L, Kuhn T, Koch M, Fuhrmann G (2021) Stimulation of probiotic bacteria induces release of membrane vesicles with augmented anti-inflammatory activity. ACS Appl Bio Mater 4:3739–3748. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.0c01136

Muñoz-Garach A, Diaz-Perdigones C, Tinahones FJ (2016) Gut microbiota and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Nutr 63:560–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endonu.2016.07.008

Muscogiuri G, Cantone E, Cassarano S et al (2019) Gut microbiota: a new path to treat obesity. Int J Obes Suppl 9:10–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41367-019-0011-7

Ñahui Palomino RA, Vanpouille C, Costantini PE, Margolis L (2021) Microbiota-host communications: bacterial extracellular vesicles as a common language. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1009508

Nakata K, Sugi Y, Narabayashi H et al (2017) Commensal Microbiota-induced microRNA modulates intestinal epithelial permeability through the small GTPase ARF4. J Biol Chem 292:15426–15433. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M117.788596

Ortega MA, Fraile-Martínez O, Naya I et al (2020) Type 2 diabetes mellitus associated with obesity Diabesity The central role of gut microbiota and its translational applications. Nutrients 12:2749. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092749

Ottman N, HuuskonenL L, Reunanen J et al (2016) Characterization of outer membrane proteome of Akkermansia muciniphila reveals sets of novel proteins exposed to the human intestine. Front Microbiol 7:1157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01157

Pabst O, Slack E (2020) IgA and the intestinal microbiota: the importance of being specific. Mucosal Immunol 13:12–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41385-019-0227-4

Park KY, Kim B, Hyun CK (2015) Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG improves glucose tolerance through alleviating ER stress and suppressing macrophage activation in db/db mice. J Clin Biochem Nutr 56:240–246. https://doi.org/10.3164/jcbn.14-116

Patten DA, Hussein E, Davies SP et al (2017) Commensal-derived OMVs elicit a mild proinflammatory response in intestinal epithelial cells. Microbiol (Reading) 163:702–711. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.000468

Pérez-Bermúdez P, Blesa J, Soriano JM, Marcilla A (2017) Extracellular vesicles in food: experimental evidence of their secretion in grape fruits. Eur J Pharm Sci 98:40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2016.09.022

Rayner KJ, Hennessy EJ (2013) Extracellular communication via microRNA: lipid particles have a new message. J Lipid Res 54:1174–1181. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R034991

Rinninella E, Cintoni M, Raoul P et al (2019) Food components and dietary habits: keys for a healthy gut microbiota composition. Nutrients 11:2393. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102393

Rodríguez-Nogales A, Algieri F, Garrido-Mesa J et al (2018) Intestinal anti-inflammatory effect of the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii in DSS-induced colitis in mice: Impact on microRNAs expression and gut microbiota composition. J Nutr Biochem 61:129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.08.005

Rome S (2019) Biological properties of plant-derived extracellular vesicles. Food Funct 10:529–538. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8fo02295j

Rosés C, Cuevas-Sierra A, Quintana S et al (2021) Gut microbiota bacterial species associated with mediterranean diet-related food groups in a northern spanish population. Nutrients 13:636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020636

Ross SA, Dzida G, Vora J et al (2011) Impact of weight gain on outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 27:1431–1438. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2011.585396

Rouxinol-Dias AL, Pinto AR, Janeiro C et al (2016) Probiotics for the control of obesity - its effect on weight change. Porto Biomed J 1:12–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbj.2016.03.005

Sanz Y (2010) Effects of a gluten-free diet on gut microbiota and immune function in healthy adult humans. Gut Microbes 1:135–137. https://doi.org/10.4161/gmic.1.3.11868

Sendra E, Sayas-Barberá ME, Fernández-López J, Pérez-Alvarez JA (2016) Effect of food composition on probiotic bacteria viability In: Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics: Bioactive Foods in Health Promotion. pp 257–269

Sharma S, Tripathi P (2019) Gut microbiome and type 2 diabetes: where we are and where to go? J Nutr Biochem 63:101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.10.003

Shen Y, Torchia MLG, Lawson GW et al (2012) Outer membrane vesicles of a human commensal mediate immune regulation and disease protection. Cell Host Microbe 12:509–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.004

Shin H-S, Gedi V, Kim J-K, Lee D (2019) Detection of Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane vesicles using DNA aptamers. Sci Rep 9:13167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49755-0

Sommer F, Bäckhed F (2013) The gut microbiota-masters of host development and physiology. Nat Rev Microbiol 11(227):238. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2974

Soundharrajan I, Kuppusamy P, Srisesharam S et al (2020) Positive metabolic effects of selected probiotic bacteria on diet-induced obesity in mice are associated with improvement of dysbiotic gut microbiota. FASEB J 34:12289–12307. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202000971R

Sung KC, Ban M, Choi EJ et al (2013) Extracellular vesicles derived from gut microbiota, especially akkermansia muciniphila, protect the progression of dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. PLoS ONE 8:e76520. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076520

Tan J, Ni D, Taitz J et al (2020) Dietary protein increases T cell independent sIgA production through changes in gut microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles. BioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.30.405217

Teng Y, Ren Y, Sayed M et al (2018) Plant-derived exosomal MicroRNAs shape the gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 24:637-652.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2018.10.001

Thoo L, Noti M, Krebs P (2019) Keep calm: the intestinal barrier at the interface of peace and war. Cell Death Dis 10:849. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-019-2086-z

Tong L, Hao H, Zhang X et al (2020) Oral administration of bovine milk-derived extracellular vesicles alters the gut microbiota and enhances intestinal immunity in mice. Mol Nutr Food Res 64:e1901251. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201901251

Toyofuku M, Nomura N, Eberl L (2019) Types and origins of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0112-2

Tulkens J, Vergauwen G, Van Deun J et al (2020) Increased levels of systemic LPS-positive bacterial extracellular vesicles in patients with intestinal barrier dysfunction. Gut 69:191–193. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317726

Tulkens J, De Wever O, Hendrix A (2020) Analyzing bacterial extracellular vesicles in human body fluids by orthogonal biophysical separation and biochemical characterization. Nat Protoc 15:40–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-019-0236-5

Viennois E, Chassaing B, Tahsin A et al (2019) Host-derived fecal microRNAs can indicate gut microbiota healthiness and ability to induce inflammation. Theranostics 9:4542–4557. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.35282

Virtue AT, McCright SJ, Wright JM et al (2019) The gut microbiota regulates white adipose tissue inflammation and obesity via a family of microRNAs. Sci Transl Med 11:eaav1892. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1892

Wang D, Xia M, Yan X et al (2012) Gut microbiota metabolism of anthocyanin promotes reverse cholesterol transport in mice via repressing miRNA-10b. Circ Res 111:967–981. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.266502

Wang K, Liao M, Zhou N et al (2019) Parabacteroides distasonis alleviates obesity and metabolic dysfunctions via production of succinate and secondary bile acids. Cell Rep 26:222-235.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.028

Wang H, Lu Y, Yan Y et al (2020) Promising Treatment for type 2 diabetes: fecal microbiota transplantation reverses insulin resistance and impaired islets. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 9:455. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00455

Woith E, Fuhrmann G, Melzig MF (2019) Extracellular vesicles—connecting kingdoms. Int J Mol Sci 20:5695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20225695

Woith E, Guerriero G, Hausman J-F et al (2021) Plant extracellular vesicles and nanovesicles: focus on secondary metabolites, proteins and lipids with perspectives on their potential and sources. Int J Mol Sci 22:3719. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073719

Xiao J, Feng S, Wang X et al (2018) Identification of exosome-like nanoparticle-derived microRNAs from 11 edible fruits and vegetables. PeerJ 6:e5186. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5186

Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PRM, Andreu Z et al (2015) Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles 4:27066. https://doi.org/10.3402/jev.v4.27066

Yang D, Chen X, Wang J et al (2019) Dysregulated lung commensal bacteria drive interleukin-17B production to promote pulmonary fibrosis through their outer membrane vesicles. Immunity 50:692-706.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.02.001

Zimmer J, Lange B, Frick J-S et al (2012) A vegan or vegetarian diet substantially alters the human colonic faecal microbiota. Eur J Clin Nutr 66:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2011.141

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This project was supported by CIBERobn (CB12/03/30002), Mineco (RTI2018-102205-B-I00, BFU2015-65937-R projects), and a Center for Nutrition Research predoctoral grant awarded to ED.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ED, FM, and SL conceived the hypothesis presented in the manuscript. ED performed the review of the literature and wrote the manuscript, which was critically revised and edited by FM, SL, and JR. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors declare that all data were generated in-house and that no paper mill was used.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Key points

1. Gut microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles could be relevant players in obesity and diabetes pathophysiology.

2. Dietary habits could influence metabolic disease outcomes by targeting gut microbiota–derived extracellular vesicles characteristics and amount.

3. Nutritional and/or pharmacological approaches based on the administration of extracellular vesicles derived from probiotic and/or gut microbiota bacteria should be explored as therapeutic strategies to treat obesity and diabetes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Díez-Sainz, E., Milagro, F.I., Riezu-Boj, J.I. et al. Effects of gut microbiota–derived extracellular vesicles on obesity and diabetes and their potential modulation through diet. J Physiol Biochem 78, 485–499 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13105-021-00837-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13105-021-00837-6