Abstract

Purpose

This national survey evaluated the perceived efficacy and safety of intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) in septic shock, self-reported utilization patterns, barriers to use, the population of interest for further trials and willingness to participate in future research of IVIG in septic shock.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of critical care and infectious diseases physicians across Canada. We summarized categorical item responses as counts and proportions. We developed a multivariable logistic regression model to identify physician-level predictors of IVIG use in septic shock.

Results

Our survey was disseminated to 674 eligible respondents with a final response rate of 60%. Most (91%) respondents reported having prescribed IVIG to patients with septic shock at least once, 86% for septic shock due to necrotizing fasciitis, 52% for other bacterial toxin-mediated causes of septic shock, and 5% for undifferentiated septic shock. The majority of respondents expressed uncertainty regarding the impact of IVIG on mortality (97%) and safety (95%) in septic shock. Respondents were willing to participate in further IVIG research with 98% stating they would consider enrolling their patients into a trial of IVIG in septic shock. Familiarity with published evidence was the single greatest predictor of IVIG use in septic shock (odds ratio, 10.2; 95% confidence interval, 3.4 to 30.5; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Most Canadian critical care and infectious diseases specialist physicians reported previous experience using IVIG in septic shock. Respondents identified inadequacy of existing research as the greatest barrier to routine use of IVIG in septic shock. Most respondents support the need for further studies on IVIG in septic shock, and would consider enrolling their own patients into a trial of IVIG in septic shock.

Résumé

Objectif

Cette enquête nationale a évalué l’efficacité et l’innocuité perçues des immunoglobulines intraveineuses (IgIV) dans le contexte du choc septique, les habitudes d’utilisation autodéclarées, les obstacles à l’utilisation de cette modalité, les populations à explorer pour des études futures et la volonté de participer aux recherches futures sur les IgIV et le choc septique.

Méthode

Nous avons mené une enquête transversale auprès de médecins intensivistes et spécialistes des maladies infectieuses au Canada. Nous avons résumé les réponses de chaque point catégorique en tant que dénombrement et proportions. Nous avons mis au point un modèle de régression logistique multivariée afin d’identifier les prédicteurs, au niveau des médecins, d’une utilisation des IgIV en cas de choc septique.

Résultats

Notre sondage a été acheminé à 674 médecins admissibles et nous avons obtenu un taux de réponse final de 60 %. La plupart (91%) des répondants ont indiqué avoir prescrit des IgIV aux patients en choc septique au moins une fois, 86 % pour un choc septique dû à une fasciite nécrosante, 52 % pour des chocs septiques d’autres étiologies médiées par des toxines bactériennes, et 5 % dans des cas de choc septique non différencié. La majorité des répondants ont exprimé de l’incertitude quant à l’incidence des IgIV sur la mortalité (97 %) et l’innocuité (95 %) lors de choc septique. Les répondants étaient disposés à participer à d’autres recherches sur les IgIV, 98 % déclarant qu’ils envisageraient d’inscrire leurs patients à une étude sur les IgIV et le choc septique. La familiarité avec les données probantes publiées était le plus grand prédicteur d’utilisation d’IgIV dans un contexte de choc septique (rapport de cotes, 10,2; intervalle de confiance à 95 %, 3,4 à 30,5; P < 0,001).

Conclusion

La plupart des médecins intensivistes et spécialistes des maladies infectieuses canadiens ont rapporté avoir une expérience antérieure d’utilisation d’IgIV en cas de choc septique. Les répondants ont identifié l’insuffisance de la recherche existante comme le plus grand obstacle à l’utilisation systématique d’IgIV dans les cas de choc septique. La plupart des répondants appuient la nécessité d’études plus approfondies sur les IgIV et le choc septique et envisageraient d’inscrire leurs propres patients à une étude sur les IgIV dans un contexte de choc septique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Septic shock ranks among the leading causes of death for critically ill patients worldwide accounting for 15% of intensive care unit admissions1,2,3 and contemporary in-hospital mortality rates ranging from 35 to 54%.4 The mainstay of treatment is prompt, appropriate antimicrobial therapy and infection source control.5 The clinical investigation of therapeutic interventions in sepsis has been notable for numerous negative trials that have not revealed effective interventions beyond antibiotics and supportive care.6 The development of new antimicrobials has slowed and antimicrobial resistance continues to emerge worldwide.7 The global burden of illness from sepsis and septic shock remains high despite existing therapies. The discovery and systematic evaluation of novel adjunctive therapies is more important now than ever.

Intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) is a plasma product derived from human serum, composed of pooled donor antibodies active against a wide range of pathogens.8 Observed beneficial effects of IVIG in sepsis have been proposed to be due to a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines, neutralizing antibodies to microbial toxins, enhanced pathogen recognition, clearance and modulation of the complement system, and down-regulation of inflammatory pathways.8,9,10,11 While the specific mechanism of IVIG benefit remains uncertain, its proposed role in immunomodulation represents an important gap in the existing armament of therapies for patients with septic shock. Immunomodulation is a therapeutic avenue distinct from antimicrobial therapy, which is particularly relevant in the context that antimicrobial resistance has been identified as one of the greatest current threats to humanity by the World Health Organization.7

Intravenous immune globulin has been evaluated as an adjunctive therapy for septic shock in multiple clinical trials of patients with varying etiologies of septic shock.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 Several high-quality systematic reviews of trials evaluating the efficacy of IVIG in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock support a survival benefit.24,25,26,27,28 Current Surviving Sepsis Guidelines, however, recommend against the use of IVIG because of heterogeneous, low-quality evidence, and the lack of large, rigorously designed randomized-controlled trials.29 Several authors have advocated for further studies to evaluate the efficacy and safety of IVIG in sepsis prior to its widespread adoption.24,26,27 Current practice patterns regarding the use of IVIG for patients with septic shock are not known.

Methods

We conducted a self-administered survey to identify reported utilization patterns of IVIG in patients with septic shock and to probe the expected value of further clinical trials on the part of stakeholders. We surveyed critical care and infectious diseases physicians practicing in academic centres across Canada. Survey domains included perceived efficacy and safety of IVIG in sepsis, self-reported utilization patterns of IVIG, barriers and facilitators of IVIG use, the population of interest for further clinical trials, and respondent willingness to participate in future clinical trials of IVIG in septic shock.

Questionnaire design was consistent with current survey science recommendations.30,31,32 We generated questionnaire items iteratively through a combination of literature review and interviews with content experts and team members until thematic saturation was achieved. We used a modified Delphi technique for item reduction. Prior to dissemination, the questionnaire was pilot-tested by collaborators and clinical fellows. The questionnaire was formatted as intended for dissemination and co-investigators assessed the face- and content-validity, comprehensiveness, and clarity of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was then administered to ten clinical fellows who were directed to time their completion and provide feedback on flow, clarity, and redundancy. The survey was translated and back-translated from English to French (eAppendix in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]).

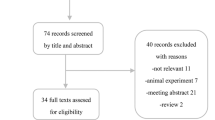

The administration and dissemination of this survey was informed by the evidence-based survey implementation guidelines described by Dillman et al. utilizing principles of social exchange theory.33 The communications flowed in a pre-determined pathway (Figure). An initial personalized introductory communication was disseminated via e-mail describing our research program and introducing the survey. One week later an invitation to participate was emailed to each potential respondent with a link to our electronic survey platform. Non-respondents received three sequential e-mail reminders every two weeks including additional invitations to participate and links to our electronic survey. Remaining non-respondents were mailed a paper questionnaire with an enclosed self-addressed postage-paid return envelope along with a CAD 5.00 coffee gift card as an unconditional reward. All electronic respondents were mailed a thank you note along with a CAD 5.00 coffee gift card. Survey completion was entirely voluntary and responses were anonymous. A consent disclosure statement was included in the invitation to participate and subsequent survey completion represented informed consent. We obtained approval from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board for this survey.

For sample size calculations, we estimated 430 critical care and 300 infectious diseases specialists practicing in academic centres across Canada based on academic centre departmental staff lists. Final respondent lists were generated by contacting each individual site and cross-referenced with electronically published staff lists from university and hospital websites. Assuming a total population of n = 730, a sample size of n = 252 provides the ability to evaluate proportions with a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of 5% (eTable 1, ESM).

We targeted a response rate of 60%. Evidence-based survey science strategies have achieved response rates of 54–71% in similar sample populations.34,35 We presented categorical item responses as numbers and proportions. We used Chi square tests to analyze sub-group differences in proportions and Cochran–Armitage trend tests for categorical variables with a natural ordering. A priori planned subgroups were physician specialty (critical care vs infectious diseases) and geographical by Canadian province. We developed a multivariable logistic regression model to identify physician-level predictors of previous IVIG use as an adjunctive therapy in septic shock. These included demographic and clinical practice variables.

Results

After contacting individual academic sites, we identified 702 potential critical care and infectious diseases specialist physicians in Canada meeting our inclusion criteria. After exclusions (Figure) we sent invitations to 674 potential respondents to participate in our survey. We received 407 returned surveys representing a response rate of 60%. Of 407 returned completed surveys, 43 were excluded based on missing key variables of physician specialty (critical care vs infectious diseases) or missing IVIG use. We analyzed results from 364 respondents (Figure).

Demographics

Survey respondents were specialist physicians in adult critical care medicine (66%, n = 241) or adult infectious diseases medicine (34%, n = 123) practicing in Canadian academic centres with Royal College of Canada critical care medicine fellowship programs. Respondents completed our questionnaire in English (84%, n = 307) and French (16%, n = 57). Survey respondents were geographically representative of the target population and reported managing critically ill patient populations in diverse practice settings (Table 1). Respondents reported practicing primarily in tertiary referral centres (96%, n = 348), and a minority in community centres (4%, n = 13) across Canada. Our sample frame included respondents with a broad range of clinical experience (Table 1).

Utilization of IVIG

The vast majority (91%; n = 333) of Canadian critical care and infectious diseases specialists reported having prescribed IVIG at least once to patients as an adjunctive therapy for septic shock. In sub-group analyses, a higher proportion of infectious disease specialists endorsed previous use of IVIG for patients with septic shock than critical care specialists did (96%, n = 118 vs 89%, n = 215; P = 0.03). Of respondents who had prescribed IVIG in septic shock, 86% (n = 312) reported administering IVIG for septic shock due to necrotizing fasciitis, 52% (n = 189) had prescribed IVIG for other (non-necrotizing fasciitis) bacterial toxin- mediated causes of septic shock, whereas 5% (n = 19) had prescribed IVIG for undifferentiated septic shock. In the previous year 61% (n = 221) of Canadian critical care and infectious diseases specialists reported prescribing IVIG as an adjunctive treatment for septic shock; the majority prescribed it only one to five times in the previous year (59% of cohort; 64% of ever prescribers) (Table 2).

Barriers to use

With respect to published clinical trials of IVIG in patients with septic shock, respondents reported that inadequate power (59%, n = 216) and inconsistency in completed trials (53%, n = 194), outdated populations or co-interventions studied (27%, n = 98), bias (30%, n = 109), choice of outcome (10%, n = 37), lack of proven safety (11%, n = 39) or efficacy (45%, n = 165) and/or lack of familiarity with published evidence (28%, n = 101) were factors that limited their clinical uptake of this therapy. Specific barriers that respondents endorsed as potentially limiting or preventing IVIG use in the management of patients with septic shock include insufficient level of evidence (91%, n = 332), cost (61%, n = 222), limited supply (28%, n = 103), and risk of toxicity or adverse reactions (23%, n = 85). Fewer respondents reported consultation with other services (17%, n = 60) and administrative paperwork (12%, n = 42) as barriers to use. When selecting potential barriers respondents were invited to “select all that apply” (eAppendix, ESM).

Knowledge gaps and future research

The vast majority of respondents expressed uncertainty regarding the clinical impact of IVIG on mortality and safety in adult patients with septic shock (97%, n = 352 and 95%, n = 346; respectively). Most respondents (68%; n = 246) reported that further prospective clinical trials are “definitely warranted” to evaluate the role of IVIG in patients with septic shock; 27% (n = 97) were unsure whether further prospective clinical trials were needed and 5% (n = 20) of respondents felt further research was not warranted. For the respondents who felt further clinical trials were not warranted, 55% (n = 11) felt the current evidence base was sufficient and did not support a beneficial role of IVIG, 35% (n = 7) responded that there was no biologic rationale for IVIG in septic shock, 20% (n = 4) felt the cost of IVIG in Canada would preclude its use regardless of efficacy and 5% (n = 1) felt a beneficial role of IVIG was already supported by the current evidence base. Respondents were willing to participate in future research, with 98% (n = 356) of respondents stating they would consider enrolling their own patients into an appropriately designed randomized trial of IVIG in septic shock. Considering the population of interest for a future trial of IVIG in septic shock, 73% of respondents (n = 264) supported enrolling patients with septic shock due to necrotizing fasciitis, 75% (n = 274) supported enrolling patients with bacterial toxin-mediated septic shock and 54% (n = 197) supported enrolling patients with undifferentiated septic shock.

Predictors of use

The majority of survey respondents (59%, n = 215) reported familiarity with the existing body of published evidence on the efficacy of IVIG in patients with septic shock. Familiarity with published literature was significantly associated with previous use of IVIG in septic shock (odds ratio, 10.2; 95% confidence interval, 3.4 to 30.5; P < 0.0001) when accounting for practice specialty, duration, type, and location (eTable 2, ESM).

Discussion

In this survey of Canadian academic critical care and infectious diseases specialist physicians, respondents reported rarely prescribing IVIG for patients with undifferentiated septic shock (as opposed to necrotizing fasciitis or other bacterial toxin-mediated causes of septic shock) and the vast majority reported uncertainty in either direction regarding the efficacy and safety of IVIG as an adjunctive therapy in this patient population. Published systematic reviews, however, support a mortality benefit for IVIG in undifferentiated septic shock when added to standard care.15,24,25,26,27,28,36 Our findings of relatively rare self-reported use of IVIG in undifferentiated septic shock are perhaps at odds with these published results. In examining what elements of the existing published studies have limited the clinical uptake of this therapy, we discovered that respondents felt these relatively small trials were under-powered for important outcomes and that inconsistencies in individual trial results, bias, and changing standards of care over time were major factors that limited respondent confidence in the conclusions of these trials and represent barriers to the practical application of this evidence.

As evidence of clinical equipoise, most respondents supported the conduct of future clinical trials of IVIG in septic shock and said they would consider enrolling their own patients into an adequately powered and appropriately designed trial. Despite our finding that respondents reported prescribing IVIG more commonly for necrotizing fasciitis and other bacterial toxin-mediated forms of septic shock they were in favour of including these patients along with those with undifferentiated septic shock in future clinical trials, further supporting the existence of clinical equipoise for IVIG in these populations.

Using multivariable logistic regression techniques, we showed that familiarity with published evidence on the efficacy of IVIG in patients with septic shock was the strongest predictor of whether respondents endorsed using IVIG for septic shock. This finding supports the need for the publication of high-quality evidence as well as the integration of a comprehensive knowledge translation strategy in any research program that hopes to see dissemination and adoption of the knowledge generated within.

Limitations and strengths

The inherent biases of self-report represent an expected limitation of this study where actual respondent practice may differ from that which they report. Additionally, our sample frame was restricted to academic centres affiliated with critical care training programs as opposed to community-based sites. This sample frame was also limited to the Canadian population, which should be considered when extrapolating these results to other national contexts. Further, our estimates of past use of IVIG were based on “ever-use” and so we were unable to quantify overall rates of use in septic shock. We will address these limitations by quantifying the actual utilization of IVIG in a population representative data set of adult patients with septic shock in a forthcoming publication. Additional stakeholders not included in our sample frame include manufacturers and conservators of IVIG as well as patients, both of whom will be integrated into the planning of a future clinical trial.

Our survey has several strengths. We developed this survey using rigorous evidence-based survey science methods to obtain accurate data and optimize our response rate. The administration and dissemination of our survey adhered to the principles of social exchange theory and was informed by evidence-based survey science methods. Our response rate of 60% is similar to the response rates of other surveys34,35,37 published by colleagues in our field who have employed similarly rigorous evidence-based methods.

Conclusions

In this national census of Canadian specialist critical care and infectious disease physicians, the reported previous historical use of IVIG in septic shock was high with a majority of respondents having prescribed IVIG at least once within the last year. Intravenous immune globulin was most commonly used for patients with necrotizing fasciitis and bacterial toxin-mediated forms of septic shock with relatively rare use in undifferentiated septic shock. The results of this survey have identified a significant evidence gap regarding the efficacy and safety of IVIG in septic shock despite ongoing clinical use of the product. The greatest barrier to the clinical use of IVIG in septic shock is inadequacy of the existing body of published research. Canadian critical care and infectious diseases specialist physicians feel that future, high-quality studies on IVIG in septic shock are required and they have expressed enthusiasm about participating in those studies. The clinical use of IVIG in undifferentiated septic shock, as a limited blood product with an as-yet incompletely characterized efficacy profile, must be justified by rigorously designed and conducted clinical trials. The results of this survey will directly inform the design of just such a clinical trial of IVIG in septic shock.

Change history

10 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-01964-w

References

Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the united states: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001; 29: 1303-10.

Brun-Buisson C, Doyon F, Carlet J, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults. A multicenter prospective study in intensive care units. French ICU Group for Severe Sepsis. JAMA 1995; 274: 968-74.

Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1546-54.

Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315: 775-87.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801-10.

Seeley EJ, Bernard GR. Therapeutic targets in sepsis: past, present, and future. Clin Chest Med 2016; 37: 181-9.

World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance Global Report on Surveillance 2014. World Heal Organization Annual Report 2014. Available from URL: https://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/ (accessed November 2020).

Gelfand EW. Intravenous immune globulin in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 2015-25.

Gupta M, Noel GJ, Schaefer M, Friedman D, Bussel J, Johann-Liang R. Cytokine modulation with immune gamma-globulin in peripheral blood of normal children and its implications in Kawasaki disease treatment. J Clin Immunol 2001; 21: 193-9.

Takei S, Arora YK, Walker SM. Intravenous immunoglobulin contains specific antibodies inhibitory to activation of T cells by staphylococcal toxin superantigens. J Clin Invest 1993; 91: 602-7.

McCormick JK, Yarwood JM, Schlievert PM. Toxic shock syndrome and bacterial superantigens: an update. Annu Rev Microbiol 2001; 55: 77-104.

Dominioni L, Bianchi V, Imperatori A, Minoia G, Dionigi R. High-dose intravenous IgG for treatment of severe surgical infections. Dig Surg 1996; 13: 430-4.

Grundmann R, Hornung M. Immunoglobulin therapy in patients with endotoxemia and postoperative sepsis–a prospective randomized study. Prog Clin Biol Res 1988; 272: 339-49.

Werdan K, Pilz G, Bujdoso O, et al. Score-based immunoglobulin G therapy of patients with sepsis: the SBITS study. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 2693-701.

Kreymann KG, de Heer G, Nierhaus A, Kluge S. Use of polyclonal immunoglobulins as adjunctive therapy for sepsis or septic shock. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 2677-85.

Rodríguez A, Rello J, Neira J, et al. Effects of high-dose of intravenous immunoglobulin and antibiotics on survival for severe sepsis undergoing surgery. Shock 2005; 23: 298-304.

Wesoly C, Kipping N, Grundmann R. Immunoglobulin therapy of postoperative sepsis (German). Z Exp Chir Transplant Kunstliche Organe 1990; 23: 213-6.

Yakut M, Cetiner S, Akin A, et al. Effects of immunuglobulin G on surgical sepsis and septic shock. Gulhane Military Med Acad 1998; 40: 76-81.

Darenberg J, Ihendyane N, Sjölin J, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin G therapy in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: a European randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37: 333-40.

Hentrich M, Fehnle K, Ostermann H, et al. IgMA-enriched immunoglobulin in neutropenic patients with sepsis syndrome and septic shock: a randomized, controlled, multiple-center trial. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 1319-25.

Behre G, Ostermann H, Schedel I, et al. Endotoxin concentrations and therapy with polyclonal IgM-enriched immunoglobulins in neutropenic cancer patients with sepsis syndrome: pilot study and interim analysis of a randomized trial. Antiinfective Drugs Chemother 1995; 13: 129-34.

Madsen MB, Hjortrup PB, Hansen MB, et al. Immunoglobulin G for patients with necrotising soft tissue infection (INSTINCT): a randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Intensive Care Med 2017; 43: 1585-93.

Masaoka T, Hasegawa H, Takaku F, et al. The efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin in combination therapy with antibiotics for severe infections. Jpn J Chemother 2000; 48: 199-217.

Alejandria MM, Lansang MA, Dans LF, Mantaring JB 3rd. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treating sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001090.pub2/full.

Laupland KB, Kirkpatrick AW, Delaney A. Polyclonal intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in critically ill adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 2686-92.

Turgeon AF, Hutton B, Fergusson DA, et al. Meta-analysis: intravenous immunoglobulin in critically ill adult patients with sepsis. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146: 193-203.

Soares MO, Welton NJ, Harrison DA, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for severe sepsis and septic shock : clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and value of a further randomised controlled trial. Crit Care 2014; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0649-z.

Pildal J, Gøtzsche PC. Polyclonal Immunoglobulin for treatment of bacterial sepsis: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39: 38-46.

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock 2012. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 165-228.

Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000008.pub4.

Nakash RA, Hutton JL, Jørstad-Stein EC, Gates S, Lamb SE. Maximising response to postal questionnaires – a systematic review of randomised trials in health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-5.

Stone DH. Design a questionnaire. BMJ 1993; 307: 1264-6.

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. London: Wiley; 2014 .

Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50: 1129-36.

Zarychanski R, Turgeon AF, Hebert PC, et al. The use of anticoagulants in severe sepsis and septic shock: a national survey of critical care physicians. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: A427.

Norrby-Teglund A, Haque KN, Hammarstrom L. Intravenous polyclonal IgM-enriched immunoglobulin therapy in sepsis: a review of clinical efficacy in relation to microbiological aetiology and severity of sepsis. J Intern Med 2006; 260: 509-16.

Koo KK, Choong K, Cook DJ, et al. Early mobilization of critically ill adults: a survey of knowledge, perceptions and practices of Canadian physicians and physiotherapists. CMAJ Open 2016; 4: E448-54.

Author contributions

Murdoch Leeies and Ryan Zarychanski contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the article. Hayley Gershengorn, Emmanuel Charbonney, Anand Kumar, Dean Fergusson, Alexis Turgeon, Juthaporn Cowan, Bojan Paunovic, John Embil, Allan Garland, Donald S. Houston, Brett Houston, Emily Rimmer, Faisal Siddiqui, Bill Cameron, Srinivas Murthy, John C. Marshall, and Rob Fowler contributed to study conception and design and data interpretation.

Disclosure

None.

Funding statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Sangeeta Mehta, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article was updated to correct Alexis F. Turgeon’s name and affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leeies, M., Gershengorn, H.B., Charbonney, E. et al. Intravenous immune globulin in septic shock: a Canadian national survey of critical care medicine and infectious disease specialist physicians. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 68, 782–790 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-01941-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-01941-3