Abstract

Background

Recent prescribing trends reflect government-led efforts undertaken in both the U.S. and Canada to decrease opioid use. These provisions reflect a reduction in the use of many potent opioids in favour of tramadol. Despite the purported benefits of tramadol over other opioids, little remains known about tramadol-associated hallucinations (TAH).

Methods

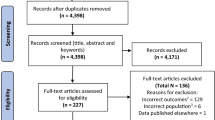

We conducted a systematic literature search in Embase, Medline, Cochrane CENTRAL, CINAHL, PubMed, Scopus, PAHO Virtual Health Library, MedNar, and ClinicalTrials.gov to find reported cases of hallucinations associated with the use of tramadol. For all corresponding cases reporting hallucinations secondary to tramadol use, we extracted data on patient demographics, medical management, and the details on hallucinations. Cases were categorized as “probable TAH” if the evidence supported an association between hallucinations and tramadol use, or “possible TAH” if hallucinations were attributed to tramadol use but the supporting evidence was weak. The “probable TAH” cases were further classified as “isolated TAH” if hallucinations were the primary complaint, or “other existing medical condition” if concurrent signs and symptoms alluded to a diagnosis of an existing medical condition. We then conducted a narrative synthesis of the available literature to contextualize these results.

Results

A total of 941 articles were identified in the initial search. No observational studies or randomized clinical trials were identified with our systematic review; only case reports were found. After a thorough screening, 34 articles comprising 101 patients reported an association between tramadol use and hallucinations. Among these 101 cases, 31 were “probable TAH” and 70 were “possible TAH”. Of the 31 cases of “probable TAH”, 16 cases were “isolated TAH” while the remaining 15 cases belonged to “other existing medical condition”.

Conclusions

Tramadol-associated hallucinations can result in auditory or visual disturbances, although multisensory symptoms have also been reported. The mechanism underlying TAH remains poorly understood and likely involves numerous receptor types. The relative risk of hallucinations from tramadol compared with other opioids remains unclear.

Résumé

Contexte

Les tendances de prescription récentes reflètent les efforts menés par les gouvernements américain et canadien pour réduire l’utilisation d’opioïdes. Ces dispositions se reflètent par une réduction de l’utilisation de nombreux opioïdes puissants en faveur du tramadol. Malgré les avantages supposés du tramadol par rapport à d’autres opioïdes, nous ne connaissons que très peu de choses en ce qui touche aux hallucinations qui y sont associées.

Méthode

Nous avons réalisé une recherche méthodique de la littérature dans les bases de données suivantes afin d’en extraire les cas rapportés d’hallucinations associées à l’utilisation de tramadol : Embase, Medline, Cochrane CENTRAL, CINAHL, PubMed, Scopus, PAHO Virtual Health Library, MedNar et ClinicalTrials.gov. Dans tous les cas correspondants rapportant des hallucinations suite à l’utilisation de tramadol, nous avons extrait les données concernant les informations démographiques des patients, leur prise en charge médicale et les détails touchant aux hallucinations. Les cas étaient catégorisés en « hallucinations associées au tramadol probables » si les données probantes appuyaient une association entre les hallucinations et l’utilisation de tramadol, ou en « hallucinations associées au tramadol possibles » si les hallucinations avaient été attribuées à l’utilisation de tramadol mais que les données probantes appuyant cette interprétation étaient faibles. Les cas « probables » étaient ensuite classés en tant que « hallucinations associées au tramadol isolées » si les hallucinations étaient la plainte principale, ou en « autre condition médicale existante » si des signes et symptômes concomitants évoquaient le diagnostic d’une autre condition médicale existante. Par la suite, nous avons effectué une synthèse narrative de la littérature disponible afin de mettre en contexte ces résultats.

Résultats

Au total, 941 articles ont été identifiés dans notre recherche initiale. Aucune étude observationnelle ou étude clinique randomisée n’a été identifiée par notre revue systématique; seuls des comptes rendus de cas ont été identifiés. À la suite d’une sélection rigoureuse, 34 articles comptant 101 patients rapportaient une association entre l’utilisation du tramadol et des hallucinations. Parmi ces 101 cas, 31 constituaient des cas « probables » et 70 des cas « possibles » d’hallucinations associées au tramadol. Parmi les 31 cas « probables », 16 étaient des cas « isolés », alors que les 15 autres appartenaient à la catégorie « autres conditions médicales existantes ».

Conclusion

Les hallucinations associées au tramadol peuvent entraîner des troubles visuels ou auditifs, bien que des symptômes multisensoriels aient également été rapportés. Le mécanisme sous-jacent aux hallucinations associées au tramadol est encore mal compris et implique probablement plusieurs types de récepteurs. Le risque relatif d’hallucinations liées au tramadol comparativement à d’autres opioïdes demeure incertain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Controversy surrounding the use of opioids for chronic, non-cancer pain remains pervasive.1 Recently, there has been an increased awareness of the adverse consequences of opioid use in the United States and Canada. Statistics show that both countries have experienced significant year-over-year growth in opioid-related deaths within the past decade.2,3,4 This has prompted federal and local governments to undertake provisions to decrease opioid utilization. For instance, lawmakers in the state of Florida have enacted legislation that imposes a three-day limit on opioid prescriptions for acute pain, with an allowable increase to seven days only when medically necessary.5 In Canada, the Minister of Health recently sought commitment from opioid manufacturers and distributors to voluntarily suspend marketing and advertising of opioids to healthcare professionals.6

In response to the increased public awareness of opioid overuse, many practitioners now heavily restrict or outright refrain from prescribing traditional opioids.7 Nevertheless, as prescriptions for these opioids were recently commonplace, changing prescription habits to satisfy newly revised best practice guidelines may prove to be challenging. For the segment of patients who require μ-agonists, tramadol has been utilized to great effect. Tramadol has partial μ-agonistic properties, which makes it suitable for treating moderate to severe pain.8 It has gained widespread acceptance for its lower relative abuse potential and favourable side effect profile.9 Data shows that prescriptions for tramadol are on the rise and may be a direct response to recent cutbacks on other prescription opioids.10,11 Prescriptions for tramadol are expected to increase even further, particularly in the US, with the recent proposal by the United States Department of Justice and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) to limit production quotas on oxycodone, hydrocodone, oxymorphone, hydromorphone, morphine, and fentanyl by an average of ten percent in 2019.12

The rise in opioid prescriptions has coincided with a significant increase in opioid-related adverse drug events.13 Among the lesser known effects of opioids, including tramadol, is the onset of hallucinations.14 This is a highly distressing phenomenon and patients are often reluctant to bring this up to practitioners for fear of being deemed psychiatrically impaired. The incidence of this adverse effect of tramadol may be further compounded by the projected increase in utilization in the near term. This scenario has the potential to significantly increase healthcare utilization and cost.15

Presently, there are relatively few reported cases of tramadol-associated hallucinations (TAH), a condition defined by neurosensory disturbances as a direct result of tramadol therapy. To aid practitioners to be more aware of this outcome as it relates to tramadol use, we performed a systematic review of the literature. We then reviewed the pathophysiology, diagnosis, risk factors, and treatment of TAH.

Methods

A systematic search of health science literature was conducted to find potentially relevant studies. The primary search strategy was for use in Embase (Elsevier Embase.com) using a mix of Emtree subject terms and text words for hallucinations, delirium, and acute confusion, combined with synonyms and trade names for tramadol taken from MeSH and Emtree entrees. The search was then translated to the following databases: Medline (Ovid Medline and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL (Ebsco), PubMed (excluding Medline), and Scopus. Additionally, a simplified version of this strategy was used in the Pan American Health Organization Virtual Health Library (VHL) Regional Portal to search LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), IBECS (Spanish Bibliographic Index of the Health Sciences), WHO IRIS (World Health Organization Institutional Repository for Information Sharing), BINACIS (Bibliografía Nacional en Ciencias de la Salud), CUMED PAHO (Virtual Health Library of Cuba and Pan American Health Organization), BBO (Brazilian Dentistry Bibliography), and PAHO-IRIS (Pan American Health Organization Institutional Repository for Information Sharing).

All searches were run on March 5, 2019. No language limits were used in the search phase and all databases were searched from their inception date to the present. Study types were not restricted, with the exception of excluding reviews by publication type in Embase, and limiting to trials only in Cochrane CENTRAL. English, Portuguese, and Spanish translations of terms were used when searching VHL. Conference papers, abstracts, registered trials, and other grey literature were searched on March 14, 2019, using the complete search strategy in Embase and simplified versions in MedNar.com and ClinicalTrials.gov. Full search strategies are available as Electronic Supplementary Materials (ESM).

At the conclusion of each database search, results were exported to EndNote citation software and deduplicated using a modified version of the method developed by Bramer et al.16 Citations were screened for inclusion using Microsoft Excel workbooks specially designed for systematic reviews.17

For eligible cases, we examined the following patient parameters: prior history of tramadol use, previous complaints of hallucinations, co-administered medications, recent tramadol dosing changes, time to hallucination following tramadol intake, specific signs and symptoms, treatments given, time to symptom resolution following tramadol discontinuation, and any recurrence of hallucinations with tramadol readministration. The cases were then organized into the following categories: 1) “probable TAH”, if the evidence supported an association between the hallucinations and tramadol use, or 2) “possible TAH”, if hallucinations were purported to occur secondary to tramadol use, but there was insufficient evidence based on the aforementioned patient parameters to confirm such an association. Specifically, cases were classified as “probable TAH” if there was a defined temporal relationship between the onset of hallucinations and tramadol intake, as well as with the resolution of symptoms following tramadol discontinuation. Cases were also classified as “probable TAH” if there was a prior reported history of hallucinations with tramadol use, if there was a recurrence of symptoms with the readministration of tramadol, if there was a recent tramadol dose escalation that correlated with the onset of hallucinations, or if there were no other factors that could account for the hallucinations. To further delineate the context in which TAH may occur, cases of “probable TAH” were further sub-categorized as “isolated TAH” if hallucinations were the only symptoms described, or as “other existing medical condition” if additional signs or symptoms were also present to indicate that the TAH were occurring in the context of an existing medical condition.

Results of systematic review

A total of 941 articles were identified, with 783 retrieved through the initial database searches, and an additional 158 articles found through supplemental grey literature searches (eFig. 1, available as ESM). After removing duplicates, 770 articles were screened based on titles and abstracts. Screeners did not see authors, journal names, or dates to reduce bias. After initial screening, 76 articles were assessed in full text, of which 44 were subsequently excluded because they did not address tramadol or hallucinations directly, did not discuss hallucinations in relation to tramadol, or were not research or case studies. One study was excluded because it was not available for assessment. Two additional articles were later identified and included after reviewing the references of the remaining eligible articles. A total of 34 studies were eventually included in the review. Among those, 27 were case studies, one was a case series, and six were original reports, representing a total of 101 patients. No observational studies or randomized clinical trials were identified with our systematic review.

Among the 101 patients where associations between hallucinations and tramadol administration were purported, 31 were cases of “probable TAH”. Of these 31 cases, 16 were “isolated TAH” (eTable 1, available as ESM). The remaining 15 cases of “probable TAH” belonged to “other existing medical condition”, including five suspected cases of serotonin syndrome, nine cases of delirium or other neuropsychiatric disturbance, and one case of angioedema with hallucinogenic features (eTable 2, available as ESM). There were 70 cases in the published literature that described “possible TAH” (eTable 3, available as ESM).

Narrative synthesis of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of tramadol-associated hallucinations

Tramadol is a synthetic opioid analog of codeine that was first synthesized in Germany in 1962. It is distinguishable from other opioids by its dual mechanism of action, which includes agonistic activity at μ-receptors and inhibitory effects on monoamine transporters. Tramadol first received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1995 as a non-scheduled drug. Nevertheless, emerging evidence of tramadol’s addictive potential, combined with escalating incidences of related emergency room visits, prompted the DEA to reclassify tramadol as Schedule IV drug in 2014.18 In a similar move, Health Canada has made recent proposals to reclassify tramadol as a Schedule I narcotic.19 While many still regard tramadol as being a safer alternative to other opioids, hallucinations remain an underappreciated complication with potential health and safety concerns.

Presentation

Approximately 39% of the general population have experienced hallucinations at one point in their lives, with olfactory and gustatory being the most common.20 In contrast, existing data suggests that hallucinations resulting from tramadol use occurs relatively infrequently. One retrospective cohort study involving over 8,500 tramadol users showed that hallucinations accounted for 0.6% of all complications relating to tramadol therapy.21 A separate report by the Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee of Australia, found that hallucinations accounted for 8.5% of all reported adverse reactions with tramadol.22 It is possible that there may be underreporting by patients of these events because of their fear of being stigmatized by family, friends, and the medical community.

The types of hallucinations associated with tramadol administration are varied (eTable 1, available as ESM). Most TAH cases that exist in the literature primarily describe auditory or visual disturbances.23,24,25,26 Keeley et al. describe a 74-yr-old palliative care patient who developed auditory hallucinations after he was prescribed tramadol for lung cancer pain. These hallucinations consisted of multiple voices singing and background instrumentation.23 Multisensory hallucinations stemming from tramadol have also been reported,27,28,29 as exemplified in the case of a 79-yr-old male who developed concurrent auditory and visual hallucinations. This particular patient described hearing rainfall and water dripping into a well, as well as seeing people in his home inviting him to go out.27 Despite the variable presentation, the consensus remains that these hallucinations may cause significant distress to patients, including suicidality.30,31

While many instances of TAH are defined solely by isolated hallucinogenic features, the published literature supports that TAH can also occur in conjunction with additional clinical findings. In many of these reports, new-onset delirium and symptoms of acute psychosis are frequently implicated or stated (eTable 2, available as ESM). Instances of TAH that feature co-existing fever, tachycardia, and tremors, frequently yield a diagnosis of serotonin syndrome. It is important to consider that our understanding of the actual incidence of isolated TAH compared with TAH in the setting of an existing medical condition, may be biased by the underreporting or omission of pertinent clinical information by the authors in each report.

It appears plausible that the various manifestations of TAH fall under a continuum of disorders that share a common underlying pathophysiologic process. Regardless, these disorders would have distinguishable clinical implications. Compared with patients experiencing additional signs and symptoms, those suffering from TAH with isolated hallucinogenic features may forgo treatment to avoid the possible stigma of being labelled with a mental illness. High clinical suspicion, combined with an empathetic approach to history taking, may elicit further insight into the nature and quality of the hallucinations.

Pathophysiology

The proposed mechanism for TAH may involve several different receptors.32,33 Nevertheless, current explanations of the pathophysiology of TAH remain speculative. Tramadol is metabolized in the liver primarily by the cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2D6 and to a lesser extent by CYP3A4 and CYP2B6).34,35,36,37 With over 100 variants, CYP2D6 is thought to metabolize 25% of the most commonly prescribed medications, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, and analgesics. Patients with altered metabolizer variants of CYP2D6 are at risk for elevated serum concentrations of either the parent drug or its metabolites and may subsequently experience an exaggerated response to the respective compound.34 The analgesic effects of tramadol are largely produced through desmetramadol, an active metabolite with a considerably greater affinity for the μ-receptors than its parent entity.38 Both tramadol and desmetramadol have been shown to antagonize muscarinic receptors and impede cholinergic transmission.38,39 Given that anticholinergic states have been shown to cause hallucinations,30,39,40 it is conceivable that tramadol and its metabolites may initiate hallucinations through this very mechanism.

In addition to possessing anticholinergic properties, tramadol is also a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI).41 Analysis of the published literature suggests that serotonin syndrome, a condition defined by excessive serotonergic activity leading to cognitive-behavioural changes, autonomic instability, and neuromuscular symptoms,42,43 is among the most commonly purported diagnosis in cases involving hallucinations and tramadol use (eTable 2, available as ESM). Furthermore, tramadol is one of the many serotonergic agents known to elicit serotonin syndrome.42 Together with serotonergic imbalances, excessive cholinergic activity at the visual cortex and brainstem are believed to contribute to the development of hallucinations, as has been suggested in patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Lewy Body Dementia.30 Tramadol’s serotonergic properties, and therefore hallucinogenic effects, may further be linked to dopamine.44 Dopamine dysregulation at various brain foci has been postulated to cause opioid-induced hallucinations.45 Serotonin receptor-mediated dopamine release at the ventral striatum is one such potential hallucinogenic pathway.44

Emerging evidence suggests that tramadol possesses antagonistic effects on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors.41 This is of particular interest for future research on TAH given that displacement of GABA from its receptor has been shown to cause generalized stimulation of the central nervous system, including the potentiation of hallucinations.46,47 Future studies on TAH may also benefit from exploring tramadol’s effects as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor,48 as well as a μ-opioid and κ-opioid receptor antagonist,49 since these properties have been shown to potentiate states of delirium and are potential pathways through which tramadol can mediate hallucinosis.

Diagnosis

There is no single diagnostic test that can be used to definitively establish the diagnosis of TAH. Furthermore, study results may often be negative or nonspecific.50,51 Imaging studies and laboratory tests may play a role in ruling out other etiologies, including psychiatric illnesses, dementia, encephalopathy, withdrawal, electrolyte abnormalities, and hypoglycemia.30,48

The literature suggests that TAH onset typically occurs within five days of initiating tramadol.25,27,28,52 One case describes symptom onset as early as three hours after initiation of the drug.53 Hallucinations that develop shortly after starting tramadol suggests increased clinical suspicion for TAH. Nevertheless, there have been reported incidences of TAH resulting after prolonged tramadol use. In one case, a 66-yr-old patient developed visual and somatosensory hallucinations 56 days after initiating tramadol therapy for cervical spine pain.29 Hallucinations in the context of pre-existing long-term tramadol therapy may also occur more frequently with recent dose escalations.54 Taken together, despite a higher likelihood of TAH with recent tramadol initiation, it is advisable for clinicians to consider tramadol when differentiating hallucinosis etiology regardless of therapy duration. Definitive diagnosis is further guided by the absence of alternative hallucinogenic factors, as well as by complete resolution of symptoms after tramadol discontinuation (eFig.2, available as ESM).

Risk factors

Several risk factors have been implicated in the development of TAH. Advanced age may be a significant risk factor, although this has yet to be proven in large-scale studies.23,27,55 In fact, greater than half of all probable TAH cases published in the literature involve patients aged 70 yr or older (eTables 1 and 2, available as ESM). This corresponds with recent data showing that emergency room visits after adverse reactions to tramadol are most common in patients aged 65 yr or older.56 Of interest is the negative correlation between age and both hepatic and renal function. Because tramadol is metabolized in the liver and eliminated by the kidneys, older patients are predisposed to increased drug accumulation and would conceivably be more susceptible to experiencing the adverse effects of tramadol.30,57 While hallucinations stemming from tramadol use appear to occur more commonly in the older population, children are not immune to this adverse complication. In rare instances, this phenomenon has been reported in children less than six years of age.58

Several comorbid conditions may also increase the risk for TAH. For example, malignancy has been described as a significant risk factor for TAH.23 Opioid-induced hallucinations are well reported in patients with terminal cancer, with some studies reporting an incidence of 10%.59,60 Pre-existing neuropathological conditions, such as a history of auditory hallucinations or hearing impairment, may also be contributory.26,28,61 This potential association between neuropathology and TAH is supported by brain imaging studies in patients experiencing TAH, which frequently reveal chronic ischemic changes and atrophy.23,28 Additionally, psychiatric disorders appear to be another strong predictor for the development of TAH. Depression, for instance, is commonly identified in patients who experience TAH.28

There is strong evidence to support that polypharmacy may play a significant role in developing TAH. Many of these cases specifically involve the use of antidepressants. The hallucinogenic effects of antidepressants, such as selective SRIs, are two-fold. First, they exaggerate the serotonergic effects of tramadol.25,50 Second, these agents reduce the capacity for tramadol metabolism by inhibiting CYP2D6, thereby increasing serum tramadol levels.57,62 Polypharmacy as it relates to TAH likely extends beyond psychiatric medications. Of note, cases of TAH have been linked to concomitant use of antibiotics, as well as with the recent administration of the flu vaccine.28,35,63 Given the prevalence of polypharmacy among chronic pain patients and its association with TAH, it may be advisable for practitioners to consider drug discontinuation prior to initiating tramadol therapy if this is desirable or appropriate.

It is important to consider the many challenges in determining the validity of the aforementioned risk factors as it relates to their role in facilitating TAH. Many of the patient comorbidities and co-administered medications that are detailed in published cases of TAH are themselves independent risk factors for the development of hallucinations.

Prevention and treatment

A thorough history and physical examination appear central to TAH prevention, risk stratification, and minimization of misdiagnosis. In certain cultures, hallucinations may be part of ordinary ritual practices and may be positively valued in the context of local beliefs.64 Discussing patients’ cultural backgrounds may help to identify individuals at risk for developing culturally sanctioned hallucinations that would otherwise be misinterpreted as TAH.65 Moreover, since cytochrome P450 CYP2D6 is central to tramadol metabolism, genotype screening for altered metabolism variants may identify patients with a predisposition for tramadol-related adverse events, including hallucinations.34 Nevertheless, genetic screening may be deemed excessive and cost-prohibitive for the purposes of tramadol therapy.

Published literature appears to advocate for careful dose titration and proper patient counselling on prescription instructions to minimize the risk for TAH. The importance of this approach is highlighted by the fact that nearly half of primary care patients are believed to misunderstand or misinterpret dosing instructions on prescription labels.66 Even with the aforementioned strategies, TAH may still manifest. Educating patients on the signs and symptoms of TAH and reinforcing the significance of seeking timely treatment may serve to improve patient outcomes should this complication arise.

A review of the literature suggests that discontinuing tramadol is the most effective treatment for TAH, with signs and symptoms typically resolving within 48 hr.23,27,29,50 Limited published cases further support the notion that patients with a prior history of TAH risk experiencing a recurrence of symptoms if they reinitiate tramadol therapy.28,35 A dose reduction may be the next preferred option when tramadol cessation is not practical. This approach may potentially eliminate hallucinations while allowing the patient to maintain an otherwise effective analgesic regimen. Discretion is required when tapering tramadol because abrupt discontinuation has been shown to precipitate withdrawal symptoms, as well as hallucinations.67,68,69 Practitioners need to make decisions regarding weaning parameters on an individualized basis.

Patients at risk for TAH may also benefit from opioid rotation, a method that involves the exchange of one opioid for another to improve analgesic response or to reduce adverse effects.70 This approach has been shown to effectively treat opioid-induced hallucinations.60 One reported case described a patient who experienced complete resolution of TAH symptoms while maintaining adequate analgesia for cancer-related pain, after tramadol was replaced with dextropropoxyphene/acetaminophen.23 When opioid rotation is undertaken, it is advisable to be mindful of the potential development of further suboptimal drug interactions. Encouraging patients to fill their prescriptions at one pharmacy might streamline prescription drug monitoring and serve as a safeguard against harmful drug interactions.56 Furthermore, the implementation of a robust pharmacovigilant reporting system to track suspected cases of TAH may provide additional outcome data that can further guide clinical treatment and reduce healthcare cost.71

Supportive care appears central to the management of TAH, although there is currently insufficient evidence to guide specific therapeutic choices. Short-term treatment with antipsychotics, such as haloperidol29 or risperidone,31 may temporize acute states of hallucinosis. There is conflicting evidence regarding the use of benzodiazepines. For instance, lorazepam has been shown to ablate symptomatic TAH.24 Conversely, alprazolam was identified as an agent capable of worsening states of hallucinosis and altered mentation in patients taking tramadol.72 Discretionary use of benzodiazepines on a case-by-case basis is advised.

Future research may explore the role of anticonvulsants and hypnotics, which have shown promising results in the treatment of idiopathic music hallucinations.61 For patients experiencing significant distress, psychoeducation and coping strategies are particularly important.65 It is incumbent on practitioners to identify patients at increased risk for psychological distress and to provide both adequate counseling and appropriate referral to a mental health specialist. The importance of clinical follow-up is suggested since many cases of TAH and most medication-related hallucinations show improved outcomes in the setting of timely intervention.30

Study limitations

Before reaching a firm conclusion to inform best practices, it must be emphasized that the narrative synthesis of evidence presented in this review is derived from case reports. It remains possible that our analysis of the literature was biased by the lack of randomized-controlled studies and an overall paucity of published information on TAH. While notable trends can be observed in existing literature to potentially explain the underlying pathophysiology, diagnosis, risk factors, and treatment of TAH, many of these trends remain speculative and have yet to be substantiated in large-scale studies. Practitioners are therefore advised to interpret the results of this review in the context of limited available evidence, potential confounding variables, and the risk for bias. Presently, there is a clear need for additional studies to further our understanding of the association between tramadol and hallucinations.

Conclusion

The current opioid crisis appears to be promoting a reduction in the use of many potent opioids in favour of tramadol. Practitioners need to be cognizant of the potential for hallucinations, a rare complication arising from tramadol use. The mechanism underlying TAH remains poorly understood and is believed to involve numerous receptor types at multiple sites in the brain. Discernment of the actual incidence of this condition has been impacted by its subjective presentation, which may lead to misdiagnosis. Tramadol-associated hallucinations may be underreported by patients because of a fear of being ostracized by family and the medical community as a consequence of the stigma of perceived mental illness. It is important for practitioners to de-stigmatize this potential adverse side effect. Once diagnosed, treatment of TAH frequently entails the discontinuation of tramadol. The question of whether tramadol is superior to other opioids with respect to having a lower incidence of hallucinations remains to be determined. Further research is required before we can determine the actual incidence and impact of TAH.

References

Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain 2004; 112: 372-80.

U.S. Department of Justice. Statement of Paul E. Knierim. For a hearing entitled: Tackling Fentanyl: The China Connection. Presented September 6, 2018. Available from URL: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-09/DEA%20Testimony%20-%20China%20and%20Fentanyl%20HFAC_0.pdf (accessed October 2019).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. What is the U.S. Opioid Epidemic? Available from URL: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html (accessed October 2019).

Sanger N, Shahid H, Dennis BB, et al. Identifying patient-important outcomes in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder patients: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2018; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025059.

Florida Department of Health. House Bill 21 – Frequently Asked Questions. Available from URL: http://www.flhealthsource.gov/FloridaTakeControl/files/HB21-FAQ.pdf (accessed October 2019).

Government of Canada. Meetings and Correspondence on Marketing and Advertising of Opioids. Available from URL: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/problematic-prescription-drug-use/opioids/responding-canada-opioid-crisis/advertising-opioid-medications/meetings.html (accessed October 2019).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Opioid Prescribing Rate Maps. Available from URL: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html (accessed October 2019).

Grond S, Sablotzki A. Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clin Pharmacokinet 2004; 43: 879-923.

Inciardi JA, Cicero TJ, Munoz A, et al. The diversion of Ultram, Ultracet, and generic tramadol HCL. J Addict Dis 2006; 25: 53-8.

Florida Health. 2016-2017 Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Annual Report. Available from URL: http://www.floridahealth.gov/statistics-and-data/e-forcse/funding/2017pdmpannualreport.pdf (accessed October 2019).

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pan-Canadian Trends in the Prescribing of Opioids and Benzodiazepines, 2012 to 2017. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2018. Available from URL: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/opioid-prescribing-june2018-en-web.pdf (accessed October 2019).

United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Justice Department, DEA propose significant opioid manufacturing reduction in 2019. Available from URL: https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2018/08/16/justice-department-dea-propose-significant-opioid-manufacturing-reduction (accessed October 2019).

Abeyaratne C, Lalic S, Bell JS, Ilomäki J. Spontaneously reported adverse drug events related to tapentadol and oxycodone/naloxone in Australia. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2018; 9: 197-205.

Sivanesan E, Gitlin MC, Candiotti KA. Opioid-induced hallucinations: a review of the literature, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analg 2016; 123: 836-43.

Lavan A, Eustace J, Dahly D, et al. Incident adverse drug reactions in geriatric inpatients: a multicentred observational study. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2018; 9: 13-23.

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc 2016; 104: 240-3.

VonVille HM. Excel Workbooks & User Guides for Systematic Reviews. 2017. Available from URL: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/x8b13xea3djpkq5/AADwdba0A4UeNkM2AF06dbh3a?dl=0 (accessed September 2017).

U.S. Department of Justice. Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Tramadol Into Schedule IV. Available from UR: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/rules/2014/fr0702.htm (accessed October 2019).

Government of Canada. Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Notice to interested parties — Proposal to add tramadol to Schedule I to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and the Schedule to the Narcotic Control Regulations. Available from URL: http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2018/2018-06-16/html/notice-avis-eng.html#ne2 (accessed October 2019).

Ohayon MM. Prevalence of hallucinations and their pathological associations in the general population. Psychiatry Res 2000; 97: 153-64.

Tsutaoka BT, Ho RY, Fung SM, Kearney TE. Comparative toxicity of tapentadol and tramadol utilizing data reported to the National Poison Data System. Ann Pharmacother 2015; 49: 1311-6.

Topliss D, Isaacs D, Lander C, et al. Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee (DRAC). Tramadol - Four years’ experience. Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin 2003; 22: 1-4. Available from URL: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/aadrb-0302.pdf (accessed October 2019).

Keeley PW, Foster G, Whitelaw L. Hear my song: auditory hallucinations with tramadol hydrochloride. BMJ 2000; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7276.1608.

Alonso MT, Rios RR, Moriñigo JD, et al. Musical hallucinations induced by tramadol. Eur Psychiatry 2007; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.01.1145.

Calvisi V, Ansseau M. Clinical case of the month. Mental confusion due to the administration of tramadol in a patient treated with MOAI (French). Rev Med Liege 1999; 54: 912-3.

Mascaro J, Formiga F, Pujol R. Charles-Bonnet syndrome exacerbated by tramadol. Aging Clin Exp Res 2003; 15: 518-9.

Meseguer Ruiz VA, Navarro Lopez V. Auditive and visual hallucinations secondary to tramadol administration (Spanish). An Med Interna 2003; 20: 493.

Kovács G, Péter L. Complex hallucination (visual-auditory) during coadministration of tramadol and clarithromycin (Hungarian). Neuropsychopharmacol Hung 2010; 12: 309-12.

Devulder J, De Laat M, Dumoulin K, Renson A, Rolly G. Nightmares and hallucinations after long-term intake of tramadol combined with antidepressants. Acta Clin Belg 1996; 51: 184-6.

Abou Taam M, de Boissieu P, Abou Taam R, Breton A, Trenque T. Drug-induced hallucination: a case/non case study in the French Pharmacovigilance Database. Eur J Psychiat 2015; 29: 21-31.

Irigoyen BA, Zulet MI. Musical auditive hallucinations secondary to tramadol administration: a case report (Spanish). Psiq Biol 2012; 19: 65-7.

Baggott MJ, Siegrist JD, Galloway GP, Robertson LC, Coyle JR, Mendelson JE. Investigating the mechanisms of hallucinogen-induced visions using 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA): a randomized controlled trial in humans. PLoS One 2010; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014074.

Kometer M, Schmidt A, Jäncke L, Vollenweider FX. Activation of serotonin 2A receptors underlies the psilocybin-induced effects on α oscillations, N170 visual-evoked potentials, and visual hallucinations. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 10544-51.

Arellano AL, Martin-Subero M, Monerris M, LLerena A, Farré M, Montané E. Multiple adverse drug reactions and genetic polymorphism testing: a case report with negative result. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e8505.

Pellegrino P, Carnovale C, Borsadoli C, et al. Two cases of hallucination in elderly patients due to a probable interaction between flu immunization and tramadol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013; 69: 1615-6.

Gardiner SJ, Begg EJ. Pharmacogenetics, drug-metabolizing enzymes, and clinical practice. Pharmacol Rev 2006; 58: 521-90.

Duflot T, Marie-Cardine A, Verstuyft C, et al. Possible role of CYP2B6 genetic polymorphisms in ifosfamide-induced encephalopathy: report of three cases. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2018; 32: 337-42.

Nakamura M, Minami K, Uezono Y, et al. The effects of the tramadol metabolite O-desmethyl tramadol on muscarinic receptor-induced responses in Xenopus oocytes expressing cloned M1 or M3 receptors. Anesth Analg 2005; 101: 180-6.

Lauretani F, Ceda GP, Maggio M, Nardelli A, Saccavini M, Ferrucci L. Capturing side-effect of medication to identify persons at risk of delirium. Aging Clin Exp Res 2010; 22: 456-8.

Ghosh S, Mondal SK, Bhattacharya A, Saddichha S. Acute delirium due to parenteral tramadol. Case Rep Emerg Med 2013; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/492685.

Rehni AK, Singh I, Kumar M. Tramadol-induced seizurogenic effect: a possible role of opioid-dependent gamma-aminobutyric acid inhibitory pathway. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2008; 103: 262-6.

Volpi-Abadie J, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Serotonin syndrome. Ochsner J 2013; 13: 533-40.

Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM 2003; 96: 635-42.

Lauterbach EC. Dopaminergic hallucinosis with fluoxetine in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1993; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.150.11.1750a.

Gitlin MC, Taylor BK, Kalarickal PL, Lonseth ED. Does dysregulation of catechol-O-methyltransferase predispose to opioid-induced hallucinations? A report of a patient with microdeletion of chromosome 22 and opioid-associated hallucinations. Pain Med 2007; 8: 84-6.

Segev S, Rehavi M, Rubinstein E. Quinolones, theophylline, and diclofenac interactions with the gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1988; 32: 1624-6.

Sangalli BC. Role of the central histaminergic neuronal system in the CNS toxicity of the first generation H1-antagonists. Prog Neurobiol 1997; 52: 145-57.

Moulis F, Rousseau V, Abadie D, et al. Serious adverse drug reactions with tramadol reported to the French pharmacovigilance database between 2011 and 2015 (French). Therapie 2017; 72: 615-24.

Roth BL, Baner K, Westkaemper R, et al. Salvinorin A: a potent naturally occurring nonnitrogenous kappa opioid selective agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99: 11934-9.

Mehrpour M. Intravenous tramadol-induced seizure: two case reports. Iran J Pharmacol Ther 2005; 4: 146-7.

Künig G, Dätwyler S, Eschen A, Schreiter Gasser U. Unrecognised long-lasting tramadol-induced delirium in two elderly patients. A case report. Pharmacopsychiatry 2006; 39: 194-9.

Ito G, Kanemoto K. A case of topical opioid-induced delirium mistaken as behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in demented state. Psychogeriatrics 2013; 13: 118-23.

Ir N, Celik Y, Balci K, Inal MT, Memis D. Visual hallucinations induced by tramadol overdose: case report. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci 2010; 30: 105-7.

Radwan A, Kilzieh N. De novo mania with psychotic features related to tramadol use: a case report. Eur J Clin Pharm 2017; 19: 60-2.

Kabel JS. Bijwerkingen-Neuropsychiatrische bijwerkingen door tramadol (Dutch). Pharmaceutisch Weekblad 2006; 141: 611-2.

Bush DM. The CBHSQ Report: Emergency Department Visits for Adverse Reactions Involving the Pain Medication Tramadol. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Available from URL: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_1965/ShortReport-1965.html (accessed October 2019).

Mahlberg R, Kunz D, Sasse J, Kirchheiner J. Serotonin syndrome with tramadol and citalopram. Am J Psychiatry 2004; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1129.

Stassinos GL, Gonzales L, Klein-Schwartz W. Characterizing the toxicity and dose-effect profile of tramadol ingestions in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2019; 35: 117-20.

Caraceni A, Martini C, De Conno F, Ventafridda V. Organic brain syndromes and opioid administration for cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 1994; 9: 527-33.

de Stoutz ND, Bruera E, Suarez-Almazor M. Opioid rotation for toxicity reduction in terminal cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 1995; 10: 378-84.

Pasquini F, Cole MG. Idiopathic musical hallucinations in the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1997; 10: 11-4.

Jeppesen U, Gram LF, Vistisen K, Loft S, Poulsen HE, Brøsen K. Dose-dependent inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 by citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1996; 51: 73-8.

Palaniappan P, Rajaraman V. Visual hallucinations: a treatment-emergent adverse effect of linezolid. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015; DOI:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13110338.

Larøi F, Luhrmann TM, Bell V, et al. Culture and hallucinations: overview and future directions. Schizophr Bull 2014; 40(Suppl 4): S213-20.

Chaudhury S. Hallucinations: clinical aspects and management. Ind Psychiatry J 2010; 19: 5-12.

Davis TC, Federman AD, Bass PF 3rd, et al. Improving patient understanding of prescription drug label instructions. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24: 57-62.

Senay EC, Adams EH, Geller A, et al. Physical dependence on Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride): both opioid-like and atypical withdrawal symptoms occur. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003; 69: 233-41.

Rajabizadeh G, Kheradmand A, Nasirian M. Psychosis following tramadol withdrawal. Addict. Health 2009; 1: 58-61.

Sundaragiri P, Vallabhajosyula S, Malhotra S. Acute neurological manifestations of atypical tramadol withdrawal. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29: S298-9.

Dima D, Tomuleasa C, Frinc I, et al. The use of rotation to fentanyl in cancer-related pain. J Pain Res 2017; 10: 341-8.

Planelles B, Margarit C, Ajo R, et al. Health benefits of an adverse events reporting system for chronic pain patients using long-term opioids. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2019; 63: 248-58.

Subaşı B. A case of altered mental status and acute renal failure due to tramadol and alprazolam usage. J Emerg Med Case Rep 2014; 5: 168-70.

Tawfic QA, Eipe N, Penning J. Ultra-low-dose ketamine infusion for ischemic limb pain. Can J Anesth 2014; 61: 86-7.

Burdge G, Leach H, Walsh K. Ziconotide-induced psychosis: a case report and literature review. Ment Health Clin 2018; 8: 242-6.

Conde LC, García MD, Rodríguez BP, Castro AM. Acute psychotic disorder secondary to the treatment with tramadol. Eur J Clin Pharm 2013; 15: 49-51.

Hallberg P, Brenning G. Angioedema induced by tramadol—a potentially life-threatening condition. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 60: 901-3.

Huang SS, Jou SH, Chiu NY. Catatonia associated with coadministration of tramadol and meperidine. J Formos Med Assoc 2007; 106: 323-6.

Jung SW. Ziprasidone for the treatment of delirium: Case studies. Clin Psychopharmacol. Neurosci 2010; 8: 111-4.

Kitson R, Carr B. Tramadol and severe serotonin syndrome. Anaesthesia 2005; 60: 934-5.

Lange-Asschenfeldt C, Weigmann H, Hiemke C, Mann K. Serotonin syndrome as a result of fluoxetine in a patient with tramadol abuse: plasma level-correlated symptomatology. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 22: 440-1.

Timmerman L, Hoek-Mensink AV. Opiates and SSRI’s: risk for serotonin syndrome. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2009; 19: S252-3.

Arend I, von Arnim B, Nijssen J, Scheele J, Flohé L. Tramadol and pentazocine in a clinical double-blind crossover comparison (German). Arzneimittelforschung 1978; 28: 199-208.

Ivanova O, Marina E, Julia G, et al. Tramadol as pain reliever in children and teenagers with oral mucositis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015; 50: S529 (abstract).

Rodriguez RF, Bravo LE, Castro F, et al. Incidence of weak opioids adverse events in the management of cancer pain: a double-blind comparative trial. J Palliat Med 2007; 10: 56-60.

Author contributions

Yuel-Kai Jean, Melvin C. Gitlin, and Keith A. Candiotti helped write and edit the manuscript. John Reynolds helped with performing the literature search and with writing the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Philip M. Jones, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jean, YK., Gitlin, M.C., Reynolds, J. et al. Tramadol-associated hallucinations: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of their pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 67, 360–368 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01548-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01548-9