Abstract

Background

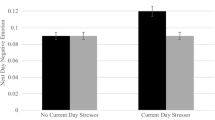

Previous studies of negative emotions and blood pressure (BP) produced mixed findings. Based on the functionalist and evolutionary perspective on emotions, we hypothesized that the association between negative emotions and BP is U-shaped, i.e., that both very high levels of negative emotions and the absence thereof are related to high BP.

Methods

Data from 7479 British civil servants who participated in Phases 1–11 (years 1985–2013) of the Whitehall II cohort study was used. Negative emotions were operationalized as negative affect and depressive and anxiety symptoms. Negative affect was measured at Phases 1 and 2. Anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed at each phase. BP was measured at every other phase. For each negative emotion measure, an average across all phases was computed and used as a predictor of PB levels throughout the follow-up period using growth curve models.

Results

Very high values of anxiety and depressive symptoms, but not negative affect, were associated with higher levels of systolic BP. However, low to moderate levels of all negative emotions were associated with lower blood pressure than the absence of negative emotions.

Conclusions

The article offers a theoretical explanation for a previously observed inverse association between negative emotions and blood pressure and underscores that moderate levels of negative emotions that naturally occur in everyday life are not associated with risks of heightened blood pressure.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I. Going to the heart of the matter: do negative emotions cause coronary heart disease? J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:323–37.

Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease: an update on current knowledge. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:337–54.

Suls J, Bunde J. Anger, anxiety, and depression as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the problems and implications of overlapping affective dispositions. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:260–300.

Negative Emotions Can Increase the Risk of Heart Disease. Psychol. Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/the-athletes-way/201405/negative-emotions-can-increase-the-risk-heart-disease (accessed 10 Jan2019).

Many Emotions Can Damage the Heart. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/depression/features/many-emotions-can-damage-heart#1 (accessed 10 Jan2019).

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298:1685–7.

Maatouk I, Herzog W, Böhlen F, Quinzler R, Löwe B, Saum K-U, et al. Association of hypertension with depression and generalized anxiety symptoms in a large population-based sample of older adults. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1711–20.

Shinagawa M, Otsuka K, Murakami S, Kubo Y, Cornelissen G, Matsubayashi K, et al. Seven-day (24-h) ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, self-reported depression and quality of life scores. Blood Press Monit. 2002;7:69–76.

Bhat SK, Beilin LJ, Robinson M, Burrows S, Mori TA. Relationships between depression and anxiety symptoms scores and blood pressure in young adults. J Hypertens. 2017;35:1983–91.

Hildrum B, Romild U, Holmen J. Anxiety and depression lowers blood pressure: 22-year follow-up of the population based HUNT study. Norway BMC Public Health. 2011;11:601.

Grimsrud A, Stein DJ, Seedat S, Williams D, Myer L. The association between hypertension and depression and anxiety disorders: results from a nationally-representative sample of south African adults. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5552.

Shinn EH, Poston WS, Kimball KT, St Jeor ST, Foreyt JP. Blood pressure and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a prospective study. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:660–4.

Keltner D, Haidt J, Shiota MN. Social functionalism and the evolution of emotions. In: Evolution and social psychology. New York: Psychology Press; 2006. p. 115–42.

Keltner D, Gross JJ. Functional accounts of emotions. Cogn Emot. 1999;13:467–80.

Rando TA. Treatment of complicated mourning. Champlian, IL: Research Press; 1993.

Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LO. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: a clinical perspective. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2008;59:73–102.

Zautra AJ. Emotions, stress, and health. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Wang M, Park Y, Lee KR. Korean-English Biliteracy acquisition: cross-language phonological and orthographic transfer. J Educ Psychol. 2006;98:148–58.

Joiner TE, Schmidt KL, Metalsky GI. Low-end specificity of the Beck depression inventory. Cognit Ther Res. 1994;18:55–68.

Adler JM, Hershfield HE. Mixed emotional experience is associated with and precedes improvements in psychological well-being. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35633.

Pennebaker JW, Graybeal A. Patterns of natural language use: disclosure, personality, and social integration. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001;10:90–3.

Lepore SJ, Smyth JM. The writing cure: how expressive writing promotes health and emotional well-being. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002.

Hershfield HE, Scheibe S, Sims TL, Carstensen LL. When feeling bad can be good: mixed emotions benefit physical health across adulthood. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2013;4:54–61.

Eng PM, Fitzmaurice G, Kubzansky LD, Rimm EB, Kawachi I. Anger expression and risk of stroke and coronary heart disease among male health professionals. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:100–10.

Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Hiding feelings: the acute effects of inhibiting negative and positive emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:95–103.

Haynes S, Feinleib M, Kannel WB. The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham study. III. Eight-year incidence of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;111:37–58.

Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4770–5.

Dich N, Doan SN, Kivimäki M, Kumari M, Rod NH. A non-linear association between self-reported negative emotional response to stress and subsequent allostatic load: prospective results from the Whitehall II cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;49C:54–61.

Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1972.

Virtanen M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG, et al. Long working hours and symptoms of anxiety and depression: a 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2485–94.

Bradburn NM, Noll CE. The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1969.

Joas E, Guo X, Kern S, Östling S, Skoog I. Sex differences in time trends of blood pressure among Swedish septuagenarians examined three decades apart. J Hypertens. 2017;35:1424–31.

Shimomitsu T, Theorell T. Intraindividual relationships between blood pressure level and emotional state. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65:137–44.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–81.

Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotional suppression: physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64:970–86.

Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:348–62.

Orsillo SM, Roemer L, Holowka DW. Acceptance-based behavioral therapies for anxiety. In: Acceptance and mindfulness-based approaches to anxiety. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2005. p. 3–35.

Sorenson SB, Rutter CM, Aneshensel CS. Depression in the community : an investigation into age of onset. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:541–6.

Ormel J, Rosmalen J, Farmer A. Neuroticism: a non-informative marker of vulnerability to psychopathology. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:906–12.

Stewart JC, Perkins AJ, Callahan CM. Effect of collaborative care for depression on risk of cardiovascular events: data from the IMPACT randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:29–37.

Lewer D, O’Reilly C, Mojtabai R, Evans-Lacko S. Antidepressant use in 27 European countries: associations with sociodemographic, cultural and economic factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207:221–6.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Danish Research Council (DFF 4183–00474) to ND.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Statement of Informed Consent

The Whitehall II study is approved by the London-Harrow Research Ethics Committee and the Scotland Research Ethics Committee. All participants who had clinical examination were asked to give written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 46 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dich, N., Rod, N.H. & Doan, S.N. Both High and Low Levels of Negative Emotions Are Associated with Higher Blood Pressure: Evidence from Whitehall II Cohort Study. Int.J. Behav. Med. 27, 170–178 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-019-09844-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-019-09844-w