Abstract

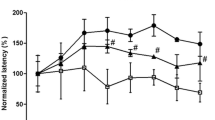

Spinocerebellar ataxia 1 (SCA1) results from pathologic glutamine expansion in the ataxin-1 protein (ATXN1). This misfolded ATXN1 causes severe Purkinje cell (PC) loss and cerebellar ataxia in both humans and mice with the SCA1 disease. The molecular chaperone heat-shock proteins (HSPs) are known to modulate polyglutamine protein aggregation and are neuroprotective. Since HSPs are induced under stress, we explored the effects of focused laser light induced hyperthermia (HT) on HSP-mediated protection against ATXN1 toxicity. We first tested the effects of HT in a cell culture model and found that HT induced Hsp70 and increased its localization to nuclear inclusions in HeLa cells expressing GFP-ATXN1[82Q]. HT treatment decreased ATXN1 aggregation by making GFP-ATXN1[82Q] inclusions smaller and more numerous compared to non-treated cells. Further, we tested our HT approach in vivo using a transgenic (Tg) mouse model of SCA1. We found that our laser method increased cerebellar temperature from 38 to 40 °C without causing any neuronal damage or inflammatory response. Interestingly, mild cerebellar HT stimulated the production of Hsp70 to a significant level. Furthermore, multiple exposure of focused cerebellar laser light induced HT to heterozygous SCA1 transgenic (Tg) mice significantly suppressed the SCA1 phenotype as compared to sham-treated control animals. Moreover, in treated SCA1 Tg mice, the levels of PC calcium signaling/buffering protein calbindin-D28k markedly increased followed by a reduction in PC neurodegenerative morphology. Taken together, our data suggest that laser light induced HT is a novel non-invasive approach to treat SCA1 and maybe other polyglutamine disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Koeppen AH. The pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia. Cerebellum. 2005;4(1):62–73.

Matilla-Duenas A, Goold R, Giunti P. Clinical, genetic, molecular, and pathophysiological insights into spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Cerebellum. 2008;7(2):106–14.

Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:575–621.

Cummings CJ et al. Over-expression of inducible HSP70 chaperone suppresses neuropathology and improves motor function in SCA1 mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(14):1511–8.

Wen FC et al. Down-regulation of heat shock protein 27 in neuronal cells and non-neuronal cells expressing mutant ataxin-3. FEBS Lett. 2003;546(2–3):307–14.

Merienne K et al. Polyglutamine expansion induces a protein-damaging stress connecting heat shock protein 70 to the JNK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(19):16957–67.

Tsai HF et al. Decreased expression of Hsp27 and Hsp70 in transformed lymphoblastoid cells from patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334(4):1279–86.

Chang WH et al. Dynamic expression of Hsp27 in the presence of mutant ataxin-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336(1):258–67.

Huen NY, Chan HY. Dynamic regulation of molecular chaperone gene expression in polyglutamine disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334(4):1074–84.

Chai Y et al. Analysis of the role of heat shock protein (Hsp) molecular chaperones in polyglutamine disease. J Neurosci. 1999;19(23):10338–47.

Fernandez-Funez P et al. Identification of genes that modify ataxin-1-induced neurodegeneration. Nature. 2000;408(6808):101–6.

Henderson B. Integrating the cell stress response: a new view of molecular chaperones as immunological and physiological homeostatic regulators. Cell Biochem Funct. 2010;28(1):1–14.

Calderwood SK, Mambula SS, Gray Jr PJ. Extracellular heat shock proteins in cell signaling and immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:28–39.

Ritossa F. Discovery of the heat shock response. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1996;1(2):97–8.

Lindquist S, Craig EA. The heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:631–77.

Velazquez JM, DiDomenico BJ, Lindquist S. Intracellular localization of heat shock proteins in Drosophila. Cell. 1980;20(3):679–89.

Muchowski PJ et al. Hsp70 and hsp40 chaperones can inhibit self-assembly of polyglutamine proteins into amyloid-like fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(14):7841–6.

Paulson HL et al. Intranuclear inclusions of expanded polyglutamine protein in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Neuron. 1997;19(2):333–44.

Cummings CJ et al. Chaperone suppression of aggregation and altered subcellular proteasome localization imply protein misfolding in SCA1. Nat Genet. 1998;19(2):148–54.

Kim S et al. Polyglutamine protein aggregates are dynamic. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(10):826–31.

Herbst M, Wanker EE. Small molecule inducers of heat-shock response reduce polyQ-mediated huntingtin aggregation. A possible therapeutic strategy. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4(2–3):254–60.

Chan HY et al. Mechanisms of chaperone suppression of polyglutamine disease: selectivity, synergy and modulation of protein solubility in Drosophila. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(19):2811–20.

Warrick JM et al. Suppression of polyglutamine-mediated neurodegeneration in Drosophila by the molecular chaperone HSP70. Nat Genet. 1999;23(4):425–8.

Sakahira H et al. Molecular chaperones as modulators of polyglutamine protein aggregation and toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99 Suppl 4:16412–8.

Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(1):11–22.

Al-Ramahi I et al. CHIP protects from the neurotoxicity of expanded and wild-type ataxin-1 and promotes their ubiquitination and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(36):26714–24.

Jana NR et al. Co-chaperone CHIP associates with expanded polyglutamine protein and promotes their degradation by proteasomes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(12):11635–40.

Vig PJ et al. Glial S100B protein modulates mutant ataxin-1 aggregation and toxicity: TRTK12 peptide, a potential candidate for SCA1 therapy. Cerebellum. 2011;10(2):254–66.

Hearst SM et al. Dopamine D2 receptor signaling modulates mutant ataxin-1 S776 phosphorylation and aggregation. J Neurochem. 2010;114(3):706–16.

Abravaya K, Phillips B, Morimoto RI. Attenuation of the heat shock response in HeLa cells is mediated by the release of bound heat shock transcription factor and is modulated by changes in growth and in heat shock temperatures. Genes Dev. 1991;5(11):2117–27.

Burright EN et al. SCA1 transgenic mice: a model for neurodegeneration caused by an expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat. Cell. 1995;82(6):937–48.

Hearst SM et al. The design and delivery of a thermally responsive peptide to inhibit S100B-mediated neurodegeneration. Neuroscience. 2011;197:369–80.

Vig PJ et al. Suppression of Calbindin-D28k expression exacerbates SCA1 phenotype in a disease mouse model. Cerebellum. 2012;11(3):718–32.

Clark HB et al. Purkinje cell expression of a mutant allele of SCA1 in transgenic mice leads to disparate effects on motor behaviors, followed by a progressive cerebellar dysfunction and histological alterations. J Neurosci. 1997;17(19):7385–95.

Jorgensen ND et al. Hsp70/Hsc70 regulates the effect phosphorylation has on stabilizing ataxin-1. J Neurochem. 2007;102(6):2040–8.

Bidwell 3rd GL, Perkins E, Raucher D. A thermally targeted c-Myc inhibitory polypeptide inhibits breast tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 2012;319(2):136–43.

Bechtold DA, Rush SJ, Brown IR. Localization of the heat-shock protein Hsp70 to the synapse following hyperthermic stress in the brain. J Neurochem. 2000;74(2):641–6.

Takemoto O, Tomimoto H, Yanagihara T. Induction of c-fos and c-jun gene products and heat shock protein after brief and prolonged cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Stroke. 1995;26(9):1639–48.

Webster CM et al. Inflammation and NFkappaB activation is decreased by hypothermia following global cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33(2):301–12.

Vig PJ et al. Intranasal administration of IGF-I improves behavior and Purkinje cell pathology in SCA1 mice. Brain Res Bull. 2006;69(5):573–9.

Vig PJ, et al. Glial S100B Protein modulates mutant ataxin-1 aggregation and toxicity: TRTK12 peptide, a potential candidate for SCA1 therapy. Cerebellum. 2011.

Duvick L et al. SCA1-like disease in mice expressing wild-type ataxin-1 with a serine to aspartic acid replacement at residue 776. Neuron. 2010;67(6):929–35.

Park J et al. RAS-MAPK-MSK1 pathway modulates ataxin 1 protein levels and toxicity in SCA1. Nature. 2013;498(7454):325–31.

Vig PJ et al. Reduced immunoreactivity to calcium-binding proteins in Purkinje cells precedes onset of ataxia in spinocerebellar ataxia-1 transgenic mice. Neurology. 1998;50(1):106–13.

Vig PJ et al. Relationship between ataxin-1 nuclear inclusions and Purkinje cell specific proteins in SCA-1 transgenic mice. J Neurol Sci. 2000;174(2):100–10.

Skinner PJ et al. Altered trafficking of membrane proteins in purkinje cells of SCA1 transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(3):905–13.

Vig PJ et al. Glial S100B positive vacuoles in Purkinje cells: earliest morphological abnormality in SCA1 transgenic mice. J Neurol Sci Turk. 2006;23(3):166–74.

Vig PJ et al. Bergmann glial S100B activates myo-inositol monophosphatase 1 and Co-localizes to purkinje cell vacuoles in SCA1 transgenic mice. Cerebellum. 2009;8(3):231–44.

Stenoien DL et al. Polyglutamine-expanded androgen receptors form aggregates that sequester heat shock proteins, proteasome components and SRC-1, and are suppressed by the HDJ-2 chaperone. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(5):731–41.

Hoshino T et al. Suppression of Alzheimer's disease-related phenotypes by expression of heat shock protein 70 in mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31(14):5225–34.

Lo Bianco C et al. Hsp104 antagonizes alpha-synuclein aggregation and reduces dopaminergic degeneration in a rat model of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(9):3087–97.

Gifondorwa DJ et al. Exogenous delivery of heat shock protein 70 increases lifespan in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2007;27(48):13173–80.

Shefer G et al. Low-energy laser irradiation enhances de novo protein synthesis via its effects on translation-regulatory proteins in skeletal muscle myoblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1593(2–3):131–9.

Hawkins D, Houreld N, Abrahamse H. Low level laser therapy (LLLT) as an effective therapeutic modality for delayed wound healing. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1056:486–93.

Santos NR et al. Effects of laser photobiomodulation on cutaneous wounds treated with mitomycin C: a histomorphometric and histological study in a rodent model. Photomed Laser Surg. 2010;28(1):81–90.

de Araujo CE et al. Ultrastructural and autoradiographical analysis show a faster skin repair in He-Ne laser-treated wounds. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2007;86(2):87–96.

Zhang H, Wu S, Xing D. Inhibition of Abeta(25-35)-induced cell apoptosis by low-power-laser-irradiation (LPLI) through promoting Akt-dependent YAP cytoplasmic translocation. Cell Signal. 2012;24(1):224–32.

Meng C, He Z, Xing D. Low-level laser therapy rescues dendrite atrophy via upregulating BDNF expression: implications for Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2013;33(33):13505–17.

Moges H et al. Light therapy and supplementary Riboflavin in the SOD1 transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (FALS). Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41(1):52–9.

Lapchak PA, De Taboada L. Transcranial near infrared laser treatment (NILT) increases cortical adenosine-5'-triphosphate (ATP) content following embolic strokes in rabbits. Brain Res. 2010;1306:100–5.

Lapchak PA et al. Transcranial near-infrared light therapy improves motor function following embolic strokes in rabbits: an extended therapeutic window study using continuous and pulse frequency delivery modes. Neuroscience. 2007;148(4):907–14.

Naeser MA et al. Improved cognitive function after transcranial, light-emitting diode treatments in chronic, traumatic brain injury: two case reports. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29(5):351–8.

Song S, Zhou F, Chen WR. Low-level laser therapy regulates microglial function through Src-mediated signaling pathways: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:219.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R03 NS070065-01 grant from the NIH. Also, we would like to thank Dr. Gene Bidwell III for his involvement in the animal studies.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest. The data reported in this manuscript has not been published or submitted for publication elsewhere. All authors have agreed to the contents of this article and there are no ethical issues involved.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hearst, S.M., Shao, Q., Lopez, M. et al. Focused Cerebellar Laser Light Induced Hyperthermia Improves Symptoms and Pathology of Polyglutamine Disease SCA1 in a Mouse Model. Cerebellum 13, 596–606 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-014-0576-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-014-0576-1