Abstract

The study aimed to illustrate the emotions related to manuscript rejection experiences and coping strategies. We conducted individual interviews and focus groups with academics receiving at least one rejection in the last year using the photovoice method. The data were analyzed using a thematic analysis based on the pictures and interviews. The findings indicated that the participants had negative emotional responses to desk rejections and peer-review rejections. We observed that the participants resorted to three strategies; avoidant strategies, neutral (neither approach nor avoidant) strategies, and approach strategies to cope with manuscript rejection. Avoidant strategies consisted of denial, self-distraction, and venting, while approach strategies included acceptance, support, planning, and positive reframing. Our study revealed that neutral strategies had humor as the only dimension. It also highlighted the significance of addressing the emotions and opinions of academics with rejection experiences. The findings also guide the coping strategies. The implications include awareness-raising activities at both individual and institutional levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academic life includes positive experiences such as learning, excitement, discoveries, and negative experiences including professional challenges, burnout, and manuscript rejection. These negative experiences are rarely discussed publicly and create “a sense of loneliness and isolation for people who presume they are the only ones affected by such setbacks” (Jaremka et al., 2020, p. 519). Studies that describe the current situation related to manuscript rejection, one of such challenges faced by many academics, can potentially help overcome these problems.

Although there have been various rejection rates reported, the rejection rate for top journals exceeds 90%, and the number is 60–80% for “mid-tier” journals (Furnham, 2021), while the overall number is almost 80% (Khadilkar, 2018). According to Hall and Wilcox (2007), 62% of the articles eventually published had been rejected at least once by other journals. Another critical issue is the length of time required to publish a study. The statistics, as expressed above, are deeply discouraging. Writing a paper with the literature review, data collection and analysis, and the write-up takes a long time. (Furnham, 2021). The work of authors who work hard to conduct research and publish their research in good journals may not be appreciated and be rejected by editors and reviewers. Journal rejection of a manuscript can be disheartening (Khadilkar, 2018).

Many studies on rejection (e.g., Dwivedi et al., 2022; Khadilkar, 2018) focus on the factors related to journal desk rejection and rejection after the manuscript review process (with peer review). These studies investigate how to avoid a journal desk rejection by developing a quality research article (Dwivedi et al., 2022; Streiner, 2007). According to Dwivedi et al.’s (2022) study based on the perspective of nine leading journal Editors, the main reasons for journal desk rejection include lack of relevance to the journals’ aims and scope, insufficient research contribution, theoretical and methodological issues, lack of novelty and research significance, poor preparation, a duplicate submission, previously rejected submissions, plagiarism and self-plagiarism, inadequate length, and language-related issues. However, the number of studies that investigate academic researchers’ experiences and feelings towards manuscript rejection (e.g., Day, 2011; Jaremka et al., 2020) is limited and conducting qualitative studies to expand studies on feelings, and coping strategies (e.g., Kim et al., 2019; Nundy et al., 2022; Venketasubramanian & Hennerici, 2013) can be considered as an essential contribution to the field. Therefore, this study aims to determine academic researchers’ experiences with journal rejection by using a qualitative research method. The study has potential contributions in two specific ways: (1) It examines academic researchers’ experience with manuscript rejection using the photovoice method, and (2) it investigates how these experiences and feelings are rendered and what associations and attributes occur, and how academics deal with these experiences or feelings. The current study has the potential to fill the gap in the literature in both ways and contribute to this debate or expand current literature.

Literature review

Rejection experience and feelings

One of the experiences in academia is scholarly publishing and hence potential manuscript rejection. Almost all scholars experience rejection (Day, 2011), and manuscript rejection is commonplace in academia (Kim et al., 2019). Such an experience is complex, challenging, and stressful compared to other experiences. Scholarly publishing is generally not a pleasant process due to the challenges while conducting the research, data collection, and manuscript submission and the high probability of journal rejection at the end of the process. “Nearly everyone goes through these experiences at some point in their academic careers” (Jaremka et al., 2020, p. 520). Furnham (2021) describes the state as at the mercy of journal ‘fetishism’ with reasons including formatting, manuscript length, restrictions, and reference style. The study discusses the experience of journal desk rejection despite such a laborious process as changing all formatting, references, and style in alignment with the new journal. A new journal refers to a journal that belongs to a different publication group with its format, reference form, and table and figure characteristics. The authors might consider editing the rejected study in a new format according to guidelines for another journal as a laborious and new procedure. Day (2011, p. 704) states that when a paper that one has labored over is rejected, it tells them that they have fallen short of the standards by which individuals are admitted into this eminent group. Besides, publishing articles creates an emotional burden on researchers with different prospects, including tenure and promotion (Graham & Stablein, 1995). Studies suggest that the publication process may lead to alienation (Driver, 2007), discouragement, disappointment, and severely damaged egos and cause negative emotional responses (Day, 2011; Furnham, 2021) also emphasizes that the experiences with judgmental, angry, bitter, anonymous reviewers will differ from many other experiences.

There have been reports and studies on the peer review process (Jaremka et al., 2020). The psychology of “publish or perish” causes significant psychological pressure on academics concerned about publishing their work (Furnham, 2021). How academics experience professional challenges such as repeated rejection, impostor syndrome, and burnout has been discussed in the Society for Personality and Social Psychology (SPSP) symposium. “Discussing these experiences is taboo and censored, creating a sense of loneliness and isolation for many, particularly young academics who assume they are the only ones affected by rejection” (Furnham, 2021, p. 843). As remarked in the symposium and related articles, the way to “normalize” the experience is through understanding the experience. Uncovering academics’ rejection experiences will contribute to normalizing this process. Furnham (2021, p. 846) explains that in “the perish or publish” race, “it takes considerable dedication to get papers published in high impact peer-reviewed journals,” which is an ego-threatening work.

The life of an academic researcher has, like all jobs, joys and sorrows. The life of an academic researcher may be predictably difficult (Furnham, 2021). Epidemiologist Kaun’s (1991) study on longevity based on a large sample of diverse professions (writers, composers, conductors, painters, etc.) suggests that writers live about ten years less than do their peers in other professions and that their average life expectancy was 61.7. According to Furnham (2021), the answer lies in hedonic calculus based on three reasons. First, completing a manuscript often takes a (very) long time. Second, writing, often challenging, demanding, and unsatisfying, is a painful and lonely process. Lastly, there is the issue of rejection which is common. This experience is well known to all academics (Furnham, 2021, p. 844).

For researchers who receive desk rejection or rejection following the manuscript review process, the result can be more painful and frustrating when writers have high expectations of the submitted manuscript. This is closely related to expectancy theory. Desk rejection or rejection following the manuscript review process can cause negative emotions because authors trust their manuscript and thus make intensive preparations for submission. Although it varies based on the author’s academic level, number of publications, and experience with the process, desk rejection can be particularly devastating for some individuals. However, when peer-reviewed manuscripts, on which the authors spent a lot of time and effort, are rejected, especially after a few important revisions, it can be emotionally damaging to the authors. After the post-review process, rejection rates vary. Even in journals with different rejection rates, it is stated that the acceptance rates increase after a few rounds of revision. While the acceptance rate in a journal with a 50% rejection rate is 97% after the fifth round, it was reported as 41% in the fourth round for a journal with a 90% rejection rate (Oosterhaven, 2015).

Academics’ expectations regarding the submission of publications have a significant impact on the emergence of the experience of rejection and the accompanying emotions. The expectation theory asserts that an individual’s behavior is motivated by the expectations that result from that behavior (Mitchell & Albright, 1971). In this context, the theory is viewed as a common function of individuals’ expectations of obtaining a particular outcome due to engaging in a particular behavior and the degree to which they value the outcomes (Agah, 2019). The expectation theory assumes that individuals evaluate the likelihood of achieving various goals in specific situations (Schunk, 1991). Vroom’s (1964) theory establishes a direct linkage between reward and performance to explain the needs of organizations and reveals the impact of the awards in direct proportion to the recipients’ willingness for the awards. In the selection process, individuals choose alternative actions based on their expected outcomes to achieve their desired outcomes (Seker, 2014). In this context, academicians submit their publications to the journal, which they expect to publish their manuscripts among different journal alternatives.

According to Vroom’s (1964) Expectancy Theory, expectancy, instrumentality, and valence factors can influence an individual’s motivation separately, but their combined effect may be stronger. Expectation is defined as an individual’s estimation of the likelihood of a certain outcome following a specific action (Vroom, 1964). The individual expectation is shaped by individual competence, the difficulty of the objective, and the degree of control over the process and expectation to achieve the objective (Estes & Polnick, 2012). The particular circumstances relating to publishing are academic qualifications, the difficulty of publishing in WoS journals, and the lack of control over the publication process (editorial and/or peer review process). It is assumed that factors besides academic competence emerge equally for all researchers in these circumstances. It can be said that the researcher has a belief that the publication submitted to a specific journal will be accepted. This level of belief will shape the expectation of the academician to accept the article, and in case of rejection, feelings of academic inadequacy will cause emotional distress.

The second element in forming an expectation is instrumentality, which is the reward for the performance resulting from the expectation. For instance, publishing in a WoS journal is difficult and requires significant effort. Despite these difficulties, publishing in WoS provides academics the opportunity to transform it into an award in the form of prestige, promotion, social identity, or belonging to a group (Horn, 2016), which reveals instrumentality.

Valence, on the other hand, is the benefit the reward (or outcome) provides to the individual. Valence is the final value that determines motivation, and the effect of motivation varies based on the significance of the award to the individual. For instance, publishing in a journal within the scope of WoS may result in academic recognition for one author, academic promotion for another, and financial incentives for yet another (Seker, 2014). The output of the expectation theory’s instrumentality stage differs in each case, as well as the significance of this output for academics differs. In the case that the article is rejected due to this difference, the researcher’s experiences and emotions based on instrumentality and valence will also emerge in different ways and levels. As a result, the author’s coping methods or strategies may vary due to different emotions that arise at different levels and in different ways.

Coping

Coping is associated with stressors or problems and negative emotions. In simple terms, stress is defined as a person’s reaction to change in their context or to a potentially dangerous situation, and “stressors” are an individual’s variations in life or dangerous situations (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

No matter the problem, if there is a rejected manuscript in question, it would be rational to mention coping strategies. While discussing coping strategies in different areas, the focus is on the overlap of a problem that is not primarily overlooked and psychological symptoms (Dohrenwend et al., 1984). According to Lazarus (2006), there is a particular relationship between an individual and the external environment during a time of stress, in which the individual exploits or exceeds their abilities and perceives that their well-being is jeopardized. Academia can contain many stressors due to the nature of the profession. One of these stressors, and perhaps the most important one in academia, is the compelling case of publishing in journals accepted in academic circles and characterized as prestigious (e.g., indexed in Web of Science). Publishing a journal article, which is a prerequisite for academic promotion, can be a source of stress. Many reasons, such as expectations in academic circles, peer pressure, and the feeling of embarrassment can trigger stress.

Teachers or academics use coping mechanisms such as psychological, social, and behavioral calming to adapt to challenging situations such as pressure to publish academically and cope with such stressful incidents and reduce feelings of distress (Admiraal et al., 2000; Gupta et al., 2021).

Efforts for coping are also present where there is stress or stress-related problem. Coping represents an individual’s cognitive, affective, and behavioral efforts to regulate specific external and internal demands (Lazarus, 2006; Lawrence et al., 2006; Folkman & Lazarus, 1985). The concept is defined by Reber (1985) as a “conscious, rational way of dealing with the anxieties of life” (p.158) and is reflected in the self-protection strategies adopted by the individual (Kashdan et al., 2006). In this study, coping with rejection can be defined as academics’ belief in their ability to manage their feelings about rejection and their confidence and ability to overcome this issue. The effective implementation of such strategies depends on the effective use of this strategy by the individual to solve problems, alleviate emotional distress, and achieve their goals. Otherwise, the stressful situation may continue or result in a “subtle avoidance or suppressed behavior” (Kashdan et al., 2006, p. 1301; Lawrence et al., 2006). Anxiety, depression, and a suite of negative emotions can persist when coping strategies fail (MacIntyre et al., 2020).

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) identify two distinct categories of coping based on the intention and function of coping efforts: problem-focused and emotion-focused (Lawrence et al., 2006). While cognitive and behavioral efforts are related to problem-oriented coping, this category contains problem-solving, planning, and effort-making strategies (Holt et al., 2005). Besides, the category includes strategies that help control emotional arousal and distress caused by the stressor (Crocker et al., 1998) without addressing the problem of emotion-focused coping, including avoidance, disconnection, and suppressed behavior (Kashdan et al., 2006). The coping strategies widely discussed in the literature are limited to active or passive coping mechanisms. Active coping refers to the ways to deal with problems and seek comfort and social support, while passive coping is, for example, self-imposed social isolation (Ashkar & Kenny, 2008; Barendregt et al., 2015; Brown & Nicassio, 1987). “Without social support, rejected authors may become isolated, expend too little energy on research, produce little meaningful work, avoid research projects, and perhaps even ultimately withdraw from scholarly activities” (Day, 2011, p. 705). According to Day (2011), silence in the face of rejection may inhibit academics from responding effectively and leads individuals to engage in dysfunctional coping strategies, which ultimately discourages creativity and impedes research efficiency.

Concerning coping with manuscript rejection, while active coping strategy refers to taking responsibility and managing the situation using the feedback received, passive coping strategies attribute responsibility to the external source. The studies in the literature focus on three strategies, including approach strategies, avoidant strategies, and neither approach nor avoidant strategies, which also cover active and passive coping strategies (MacIntyre et al., 2020). There are six subscales for approach strategies: (1) acceptance, (2) emotional support, (3) positive reframing, (4) active coping, (5) instrumental support, and (6) planning. Avoidant strategies also consist of six subscales. These are (1) behavioral disengagement, (2) denial, (3) self-distraction, (3) self-blaming, (5) substance use, and (6) venting. Finally, neither approach nor avoidant strategies include (1) humor and religion. In practice, we can conclude based on our observations that the rejected academics can use some of the subscales of the three strategies individually or simultaneously.

Support seeking is often considered an effective way to cope with challenging or stressful incidents (Mortenson, 2006). Studies on comforting and communication (e.g., Burleson & Goldsmith, 1996) show that people prefer supportive messages that acknowledge and legitimize their sad feelings rather than messages that focus on problems or distract authors from the issues. The preference for emotion-focused social support has also been confirmed across cultures (Mortenson, 2006. p. 129).

According to a different perspective, the literature defines rejection coping strategies as “saving face” behavior (Berk, 1977), support groups (Fielden & Davidson, 1998), seeking feedback (Fetzer, 2004), and not taking rejection personally (Evans et al., 2008). The research of Evans et al. (2008) on women revealed four primary coping strategies: (1) feeling bad – attributed to self; (2) feeling bad – attributed to others; (3) feeling bad – but positive about the future; and (4) feeling positive and not taking it personally.

In Venketasubramanian and Hennerici’s (2013) study on stages of grief and handling rejection, the following stages are listed: shock, denial, anger, bargaining, and acceptance. The state of shock refers to the receipt of notification of rejection. While in the denial stage, one may believe that this rejection is not true, during the stage of anger, one might curse the editor or consider writing a strongly worded response. At the bargaining stage, one could write to the editor seeking a second review, which is usually not recommended. In the final acceptance stage, one revises the paper as necessary and submits it to another journal.

Some research on academic failure (e.g., Mortenson, 2006) focuses on negative emotions (disappointment, frustration, shame, and embarrassment) and self-coping strategies or seeking social support. External traumatic activities that arise from specific facets of their academic careers can impact the perceptions and assessments, which can also account for academics’ use of coping mechanisms (Gupta et al., 2021).

Method

Photovoice, an action research tool originally developed by Wang and Burris (1997), is a visual method that focuses on participant-led photography (Cluley, 2017). In this method, participants can help other people address these issues by discussing their problems in more detail through the photos they provide (Tanhan & Strack, 2020). The sampling, procedures, analysis, and ethical considerations regarding the photovoice method applied in our research are described below.

Sampling

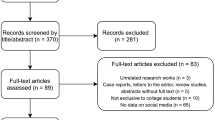

Since this study focused on academics who received a manuscript rejection, the sample group consisted of academics with rejection experience. Criteria for participation in the research group included holding at least a doctoral degree, publishing in an SSCI or Scopus indexed journal, and receiving at least one rejection (desk or after peer review) in the last year since the data collection began. Because we investigated rejection experience, recruiting people who met these criteria naturally overlapped with the research aims. We blended purposive sampling, a sampling method widely used in qualitative research, and snowball sampling based on the recommendations of people who had received rejections. To determine the sample size, saturation point, the most commonly employed concept for estimating sample sizes in qualitative research, was used (Anderson et al., 2014). The number of samples in photovoice research is determined according to the level of data saturation, like in most qualitative research. Studies conducted with seven students (Latz, 2012), thirteen mothers (Booth & Booth, 2003), and twenty young adults (Ripat et al., 2020) could be used as examples in the literature. In our study, 27 samples represented the saturation point, and it is reasonable to say that this number is adequate for photovoice work. Participants in the current study were recruited from 15 universities in four regions of the country. The total number of participants consisted of 27 academics, including 12 women and 15 men. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the participants.

Procedures

Participants were informed that the interview would take around 45 min. Participants filled in demographic and publication questions before starting the interview that lasted 32 to 67 min (M = 48.33, SD = 8.34). Participants were contacted via telephone or WhatsApp and interviewed face-to-face, by phone call, or in Zoom to discuss their experiences and photos at their convenience. Most of the interviews (21 participants) were conducted by telephone, video phone call, or Zoom due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and six participants were interviewed at a place where they felt comfortable arranging a common place to meet with the researcher. Regarding the face-to-face interviews, the participants were interviewed at their workplaces, homes, or cafes. All participants took photos with their own smartphones, provided images reflecting their experiences, or drew and photographed the image in their minds.

The following interview questions were used to measure rejected writers’ experiences of emotions and coping strategies: (a) What do you think about article rejection in general? (b) Could you share your thoughts on desk rejection and peer review rejection after the reviewing process? (c) Could you describe the process of your manuscript that was rejected in the past year and the emotions you felt at the time? (d) Could you explain how you felt when you received a desk rejection and how you felt when you received a rejection following the reviewing process? (e) Could you provide an image that best captures your feelings regarding the rejection you received from a desk or following the reviewing process? f) What do you do to cope with the emotions you experience the following rejection? (g) Could you share an image of how you deal with rejection and the method/strategy you used? Additionally, to encourage participants to create a context or tell a story about each photo associated with their rejection experience, they were asked the following questions: What made you choose this photo/visual image; what is happening in this photo; how does this photo make you feel? The interviews were carried out in a flexible and conversational style to overcome the difficulties of accessing the participants’ social and psychological worlds and provide more information. Furthermore, probe questions were used to gain richer information and clarify answers.

The data of our study were collected using a combination of methods, including individual interviews, photo/visual images, and focus groups, as also applied by Ripat et al. (2020). Photovoice is a critical and participatory data collection method promoting participants’ authority (Wang & Burris, 1997). In this method, traditionally, individuals are provided with cameras and asked to take pictures of the things that represent their experiences, discuss the meanings attributed to these pictures, and identify opportunities to address social change or action. In this study, participants were asked to take photos with their mobile phones instead of cameras due to current situations with technological affordances or share photos representing their experiences and feelings because of the Covid 19 Pandemic conditions and their own demands. As a result, 24 photos taken by the participants and 17 copyright-free photos were obtained from a digital medium or the Internet. two participants preferred to draw the images in their mind instead of sending a photo.

First, individual interviews were conducted with volunteer participants. Then, they were asked to take photographs representing their rejection experiences or share visual images depicting their feelings and experiences. Upon taking and sharing photos (1 to 81 days), a second interview was conducted (via telephone, Zoom, or face-to-face) with participants to submit their photos and captions describing their experiences, feelings, or coping. Finally, participants were invited to participate in a focus group at the end of the interview and photo data collection to discuss their photos and experiences collectively. The study included eight participants who shared their knowledge and experiences about the themes and results obtained, by participating in the focus group. The focus group lasted approximately 67 min.

Analysis

Photovoice studies benefit from both the thematic analysis approach of Braun and Clarke (2006) and the grounded theory analysis (e.g., Jurkowski, 2008; Teti et al., 2013) approach. In this study, a thematic coding approach was applied to analyze the qualitative photovoice data (interview, photo/visual images, and focus group), using grounded theory methodology (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Corbin & Strauss, 1990). Accordingly, the research team integrated two coding processes for thematic analysis: (a) systematic inductive coding and (b) deductive analysis by the research team members to triangulate findings. Deductive analysis was conducted with regard to the perspectives of the rejected authors on emotion and coping. Upon receiving the pictures taken by smartphones and those shared with us, we processed and encoded them considering the interview dataset. In other words, photos or visual images have been added to the interview transcripts to aid the interpretation. Two researchers scrutinized the digitally recorded interviews and the comments on the images and created the initial codes upon achieving a saturation point. The initial coding was completed by these researchers individually. Subsequently, the two researchers discussed these codes to reach a consensus and made minor or necessary changes. Subsequently, the codes were grouped to represent potential themes. A member check process was carried out by three volunteers participating in the research to verify the emerging themes. Additionally, the themes emerging from the interview and photo datasets were compiled and presented to the participants in the focus group for verification. The focus group interview was recorded in Zoom and analyzed similarly as described above, and we combined these data with the primary dataset.

Quality criteria

In addition to the data collection technique, data analysis, and ethical issues (Anastas, 2004) used to evaluate quality elements in qualitative research, the literature focuses primarily on reliability, validity, sampling, and generalizability (Collingridge & Gantt, 2008). Reliability in qualitative research refers to the use of accepted data collection and analysis techniques and reveals rich and meaningful definitions of the phenomenon being studied. Validity is demonstrated in qualitative research by selecting a method appropriate for the measured phenomenon based on the research problem and applying this method in a consistent, justifiable, and rigorous manner. Triangulation, respondent validation, clear procedures of data collection, reflexivity, attention to negative cases, and fair dealing are emphasized when evaluating the validity of qualitative studies (Mays & Pope, 2000). When discussing the quality of qualitative data, trustworthiness is used more commonly in qualitative research than reliability and validity (Anastas, 2004). Purposive sampling (Creswell & Poth, 2016) is commonly employed in qualitative research, as it is based on selecting a sample that is appropriate or most representative of the subject. Generalizability in qualitative research is handled more within the context of analytical generalization; it involves a rational judgment of the extent to which the findings of one study can be used as a guide to what might occur in another situation (Kvale, 1994). Analytical generalization is based on the logic that researchers point out the similarities (and differences) between situations (Collingridge & Gantt, 2008). Consistent with the above-mentioned quality elements, eight quality criteria in qualitative research were derived from Tracy’s work for a study on photovoice (2010). These criteria are the worthy topic, rich rigor, sincerity, credibility, resonance, significant contribution, ethical issues, and meaningful coherence (Cox & Benson, 2017). In this photovoice study, it is possible to state that the reliability, validity, sampling, and generalizability criteria stated above as quality elements have been met.

Various measures have been taken to increase the rigor and trustworthiness of the study. The members of the research team read all written documents and photo stories to ensure accuracy. The research team supported the people participating in the research by utilizing the rejection experiences embedded in the themes, stories, and visual images, which the content analysis uncovered. All data (interview texts and visual images) and comments based on the analysis were reviewed by at least two research team members to ensure rigor. The themes from the analysis were determined using different data sources and support from multiple research team members to implement methodological triangulation. Additionally, data collection continued until no new themes emerged (saturation), and reliability was ensured through iterative data collection by continuously analyzing the data (Frambach et al., 2013).

Ethical considerations

The current study was reviewed and approved by the Social and Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Afyon Kocatepe. The individuals participating in the research were informed about the purpose of the research project, that their participation in the study was voluntary, and that they could withdraw from the study without facing any problems. In analyzing the photos and visual images, we complied with Mitchell’s (2011) points on conducting visual research. For this reason, we highlighted the importance of taking photographs of objects, places, or animals and avoiding photos or visuals that would reveal people’s identities (e.g., blurring on people’s faces). All participants received informed consent in the written or online forms. The participants have been guaranteed confidentiality, and any personally identifiable information has been removed before and during the analysis and in reporting the results.

Results

Expectancy

The authors explore journals to publish their work when they begin to write and during the writing process. They create a list of journals in the searching process, checking previous studies published in these journals and comparing them with their work. Academics expect their articles to be published in these journals and submit their work using the manuscript template. In this phase, most participants (P2, P6, P13, P19, P21, P22, P23,, P25, P26) submit their manuscripts to a journal in which they presume an acceptance, while a smaller number of participants (P4, P5, P8) pursue a submission with a journal where they have no expectations of publishing or consider it extremely unlikely. The expectation, in this case, is to receive the reviewers’ comments from one journal to submit the manuscript to another journal. Most participants ensure that their manuscript fits within the journal’s scope and have high expectations for publication when submitting their article.

Rejection experience and emotions

The manuscript can be rejected in the following phases; desk rejection and rejection after the first round of review and several rounds of review (first, second, or third revision). The emotions that rejection arises and the extent of such emotions vary based on the type of rejection.

Our interviews showed that the authors receiving desk rejection addressed the editor’s feedback in two ways. The first was an immediate desk rejection. Although it caused a shock, the author developed a defense mechanism recognizing the advantage of immediate response to initiate a new submission process with another journal without much time loss. Some participants interpreted the editor’s immediate rejection time on the basis of prejudice against the author’s nationality or religion (e.g., P16, P3, P22, P23, P27). The participants appeared to have experienced stress, curiosity, and anxiety when the manuscript was with the editor for an extended period. Although a long wait time increased the probability of rejection, it also revealed that the authors did not lose hope completely (P18, P21, P26, P27). It aroused a negative emotional state when the participants received manuscript rejection after a long wait time. One participant who received a desk rejection after checking their emails with high expectations expressed disappointment, sadness, and vulnerability through the following quote related to the picture 1a below.

When I see an email from a journal with ‘Decision …’ as the subject line, I always feel a sudden adrenalin rush. I feel my heart rate increasing as I open and start reading the email. This usually starts positively – there is an anticipation of some great news. I feel a naïve happiness and excitement, just like the dog in the first picture. When I realize that the news is not positive, the initial high state immediately turns into a low state, and the excitement is replaced with disappointment. I feel sad and almost vulnerable, similar to the dog in the second picture. This negativity is usually transient, but definitely intense, especially after the initial anticipation (P6, Fig. 1a).

One of the negative emotions experienced by those who were rejected is disappointment. The expectation of positive news causes a greater negative emotion in the individual. To support this feeling, another participant sent a picture of an empty gift box to represent rejection with the following quote attached.

If I am going to compare rejection to something, I would say it is like a gift box you receive that comes out empty. You receive it with expectation, but it turns out to be empty. That is a disappointment (P21, Fig. 1b).

The other emotions that desk rejection creates in authors are inability and failure. Authors who received a desk rejection are preoccupied with feelings of incapability, and the feeling of being successful can be characterized as a precursor to inability. Two other participants similarly sent a photo of an arrow missing the target in the dart and expressed their feelings as follows.

An editor’s initial perception of a manuscript is closely connected with their mood when they first receive the article. In my opinion, getting the article through the editor is more about the editor’s bias than its content. The editor chooses manuscripts as depicted in this picture (P3, Fig. 2a).

I am an academic interested in archery. I consider manuscript rejection in relation to the sports I am professionally interested in. I feel the same way about rejection as I feel about a missed shooting, an overshooting. Lots of mixed negative emotions (P13, Fig. 2b).

Desk rejection caused the participants to feel intense anger along with other emotions such as shock, disappointment, and sadness. In the case of desk rejection, the participants expressed experiencing mixed emotions, including shock, surprise (P6), disappointment, anger (P14, P16, P19, P24, P25, P26,), sadness (P15, P19, P24, P25, P26), worthlessness (P21, P27), inefficacy, severely shattered ego, and discouragement (P16, P27). The followings are the quotes from the pictures sent by the participants who were upset about the editor’s rejection decision and those constantly rejected by the editor.

I get really angry if I am rejected by the editor, but I respect the peer review rejection. I read and think about the reviewers’ reasons for rejection, evaluate the lessons to be learned, and see it as an improvement opportunity to look ahead (P12, Fig. 3a).

…The pencil case represented the SSCI-indexed journal containing colorful highlighters (quality articles) that wrote excellently on many topics. …The cap, in this case, was the journal’s editor. After receiving so many rejections, what I felt was a realization that I was forcing myself to sharpen my way into the journal, just like the pencil in this picture. Yet, I could not write an article qualified enough to convince the editor to open the cap (P5, Fig. 3b).

In brief, many participants stated that desk rejection created more intense negative emotions than peer-review rejection. However, the limited number of authors in the study (P23, P27) who published eleven or more publications, stated that they have experiences in the submitting process and found the desk rejection reasonable and understandable. They also emphasized that desk rejection did not affect them emotionally and that the rejection decision was the authors’ fault.

At the end of the peer-review process, if the article was rejected in the first round, the participants (P1, P11, P25, P27) expressed feeling shocked about the reviewer rejection, as they did about desk rejection. Following the shock, they felt anger, disappointment, and failure. As little can be done following a shocking rejection, authors who face anger, disappointment, and failure feel desperate. The quotations related to the image describing the feeling of shock and desperation are as follows:

After a long preparation period, I was shocked to receive a rejection from the first journal I sent my article to. Later, when my article, which I revised based on the reviewer criticism, was rejected by other journals. I felt like a burning candle trying to illuminate the darkness (P7, Fig. 4a).

What I feel when I receive a rejection is absolute devastation. I feel like a collapsed wall. Worn, defeated, surrendered. So scattered (P4, Fig. 4b).

Following these initial feelings, the participants’ sense of curiosity predominated, and the author attentively read and interpreted the reviewer reports. Nearly all participants stated having a negative first reaction when reading these reports. However, in reviewing the reports, some participants evaluated the feedback positively and agreed with the comments. They also expressed self-criticism regarding the rejection decision, stating that they were blinded by their work during an intense research process, and the reviewers’ feedback enabled them to view the article from a broader perspective (e.g., P2). However, the participants (e.g., P6, P12, P17, P22, P27) who found the reviewers’ comments unjust and insufficient after reading the reports stated that their feelings of disappointment, anger, humiliation, worthlessness, and failure gradually increased.

One of the noteworthy points about peer review rejection was the round of revision in which the manuscript was rejected. If the participant’s manuscript (P10, P24, P25, P26, P27) was rejected after two or more rounds of revision, the rejection emotions were more intense. The reason was that the participants presumed to fulfill the requirements for manuscript revision and expected their article to be accepted, and when their expectations failed, they experienced a more intense state of shock.

The interviews demonstrated that the rejection experience varied based on the participants’ academic title, submission experience, number of (co-)authors, number of previously published articles, and number of rejections. We observed that participants’ first rejection caused emotions such as discouragement, self-questioning about the profession, and hopelessness (P4, P5, P27), while the intensity of such emotions decreased over time as the number of rejections increased. Additionally, such variables as the number of authors, whether or not one is the corresponding author, the work’s contribution to one’s academic promotion, and the author’s contribution to the study impacted the intensity of these emotions. For example, one of the participants stated that they were more upset with the rejection decision because the co-author needed the publication to apply for associate professorship (P14).

Another observation was the participants’ despair of beginning a whole new process for another journal after the rejection (P6, P14, P19). The selection of a journal, following its submission guidelines and expecting news from the editor was considered reliving an experience and seen as a state of Déjà vu. Participants may feel frustrated, overwhelmed, humiliated, oppressed, and worthless after rejection and experience a loss of excitement and desire for a new publication process. The quotes attached to the two pictures sent by the participants are presented below.

The moment you feel you have reached the perfect version and take a deep breath, it falls apart and starts from scratch. Just like that moment when you are tired after a dance practice, sit in a corner and look at your shoes feeling that tiredness (P17, Fig. 5a).

You belittled me, treated me with prejudgment, disregarded my efforts, so you easily neglected my work and trampled me with your power (P16, Fig. 5b).

Avoidance strategies

Denial

One of the most commonly used coping strategies was denial. This strategy was defensive rather than confrontational because it indicated a refusal to recognize the problem. In other words, it was defined as rejecting a rejection. Denial or rejection refers to the fear when authors face the editor or reviewers’ rejection decision and its rationale. “Küçük Emrah” (Little Emrah), a movie character in Turkish cinema depicting a child with life struggles, generated a metaphorical usage in the Turkish culture to depict someone under severe conditions. In this case, the metaphor was relatable to explain denial and rejection, and the discourse of ‘Emrah’a Bağlamak’ (a state of self-pity) was rhetorically associated with the rejection experience generating intense emotions. This tragedy-focused perspective revealed an aspect the participants often experienced personally and did not express outwardly. The participants seemed to attribute the rejection decision to the editor and reviewers’ biased and unfair judgment rather than the quality of the manuscript. Moreover, one participant tried to explain the rejection by stating, “the reviewer had a trauma relating to my country.” Denial can also be characterized as a strategy in which ‘blame attribution’ (co-author, reviewer, editor) is exhibited in coping with emotions.

Self-distraction

This strategy enabled the authors to remain busy with other work to distance themselves from the rejection or avoid reviving the experience. After the rejection, the participants gravitated to focus on other studies, which we categorized as a self-distraction strategy. Distraction was another post-rejection coping strategy commonly addressed by the participants. The experiences common to the interviewees formed the main indicators of this strategy. For example, one of the participants (e.g., P21, P24) stated that they went for a walk in Rome, Italy, and talked to their family on the phone, while another participant preferred to ride a motorcycle as a self-distraction activity (e.g., P20) after receiving the rejection decision. Other participants mentioned going out for a coffee (e.g., P2), going to class to walk away from the rejection (e.g., P17), and clearing their heads by doing useless things, not concentrating on anything particular. Two participants’ quotes attached to the pictures, one going for a motorcycle ride and another walking away from their present environment, are presented below.

The findings showed that many participants’ views of leisure motivation activities supported the self-distraction category. Overcoming this intense and negative affective state and the laborious process was interpreted as a way to return to one’s regular rhythm. The self-distraction mechanism showed the ways in which participants found or participated in various leisure activities or proceeded with new or existing academic studies.

Venting

The participants accumulated negative emotions and internalized these emotions in the publication process. The venting or expression of such internalized emotions served as a relaxation mechanism. Emotional venting included sharing the rejection decision with the trusted and respected academics in one’s academic circle. In this sense, venting refers to the author’s decision to communicate reviewer comments and their emotions about the shortcomings of their work with their social network. Thus, one seeks relief by disclosing their situation to others and venting, which helps overcome the problem psychologically. At the end of the interview, one participant (P5) admitted to the interviewer that they felt a sense of relief expressing their feelings, which was evaluated as an important indicator of venting. In general, many other participants implicitly mentioned this coping mechanism. During the interviews, the participants emphasized that rejection was expected and should be discussed with others. Rejection was considered a reference point for overcoming the negative experience both institutionally and personally. The difference between the venting and support strategies is that venting sometimes includes negative discourses (e.g., bad language, profanity), while support indicates a potential to take positive action with emotional support.

Neutral

Humor

Humor is one of the mechanisms or strategies used to neutralize and overcome rejection. The person who receives rejection attempts to legitimize it with jokes or humor. Humor can help authors regain a sense of control. It enables authors to accommodate criticism about their rejected papers. One of the interviewees (P5) stated that if the Turkish Academy of Sciences (TÜBA), one of the important scientific institutions in Turkey, had a “Rejected Manuscript Champion” award, they could be a candidate and easily win the award. The participant had an extremely pleasant facial expression while making this remark and thus normalized and neutralized the situation. Similarly, another participant (P22) expressed the situation with a humorous approach.

Think about it. By the time I got myself a cup of coffee and came back, I got rejected, so fast and nicely that I must get a “rejection champion of the year” award, an Oscar, so to say. I am not giving up on this award. I dedicate this award to all those that have been rejected (P5, Fig. 7a).

When I got the rejection letter, I felt like injured a person by a mule kick. I consider the situation as fun and try to get over it that way (P22, Fig. 7b).

Approach strategies

Acceptance

The majority of participants in the interviews commonly shared mixed negative emotions and dispersed feelings resulting from the rejection experience. They addressed physiological changes alongside the feelings of shock, sadness, surprise, disappointment, and unhappiness (P10) when their article was rejected. To get rid of these negative emotions, some participants mentioned going for a long walk, sitting around, watching a TV program, or sleeping. Participation in such activities established the basis of a passive strategy called self-distraction. Eventually, this initially passive process became a channel to acceptance. The next stage was reading the reviewer report and trying to understand why the study was rejected. At this stage, the author carefully read the reports. The participants mentioned having accepted the rejection decision of the journal, whether or not the reviewer feedback convinced them (e.g., P12, P9). One participant made the following remark about the picture below, indicating that they were aware of their knowledge and competence and accepted the rejection decision yet refused to be convinced.

This tail is quite long, which shows the extent of my knowledge and competence. You didn’t notice me. I progressed with my knowledge, and now you have to notice me (P16, Fig. 8a).

Support

Another strategy that followed acceptance was support. While these support mechanisms consisted of consultations among the authors, immediate family such as spouses (e.g., P14, P10, P27) or social circles also provided support. Some participants quite marginally stated to have tried overcoming rejection by sharing their feelings with objects (such as toys) with attached significance.

While thinking aloud about the reviewers’ feedback, I mostly share with my goat (a toy) and read it aloud. I will find the answer there. It is, in fact, my dialogue with the goat inside me, but I somehow objectify it. The goat reminds me of the challenge I have chosen by doing academic work and that I must excel at it. It allows me to imagine that I will overcome this rejection and strive to do better (P9, Fig. 8b).

Considering the support strategy from a broader perspective, we observed that the individuals shared their experience with other people who had also experienced rejection and thus normalized it, which represented the confines of support.

Planning

Planning was the process of trying to find a strategy for what the participants would do after accepting the rejection and deciding what steps to take next. At this stage, the participants decided on the journal to submit their manuscripts and which revisions to consider. They seemed to have experienced this process differently. Some authors sent their papers to another journal without undertaking any revisions after receiving the rejection decision by simply following the submission guidelines of the new journal. This planning process appeared to be more common among the participants who received desk rejection. Another planning method was to reconsider the study according to the reviewers’ criticisms based on the suggested revisions.

The transition to the planning stage varied for the participants. Some participants indicated that they did not return to the study and slept on it for a long time after accepting the rejection decision (e.g., P19, P21, P22, P27), whereas others (e.g., P2, P6, P14, P18, P19, P24, P26) chose to initiate a planning process immediately after the rejection. Figure 9 is an example of the planning strategy, which represents proceeding from the reviewer feedback, and the related quotes are presented below.

I keep all my rejection files, print out the reviewer reports, and read them repeatedly even if it hurts me. It is alright to shed tears and be angry at such times. It is even one’s right to do so because such intense work has not been understood and thus subjected to serious injustice!!!….but right after this, even before the sadness ends, different emotions blossom in me, which is part of my temperament, I know. A fresh hope blinks through the sadness and says shyly, “doing better is possible; try harder”… That is when a white paper comes out… It is the time for the old to be kept away, and the new to come to light (P10, Fig. 9a).

To me, rejection is like a plant trying to grow without water. Coping, on the other hand, is trying to grow nevertheless (P15, Fig. 9b).

Positive reframing

The participants felt strong academically due to receiving a manuscript rejection, discovering deficiencies in the planning stage of their study, and making revisions based on peer comments. In this sense, the shock of the rejection decision resulted in a good management process and the implementation of a positive coping strategy. In such a case, authors struggled for an academic triumph by transforming a negative situation into a positive experience. They revised, reinforced, and re-edited their rejected articles, and as the metaphor goes, they rose like a “phoenix” from the ashes. On the one hand, new experiences, disappointments, and disenchantment with the academic lifestyle weakened individuals, causing them to collapse. On the other hand, academics became more resilient, persistent, and knowledgeable in the following manuscript submission process with meaningful and constructive reviewer feedback. This transformation depended on the academic hierarchy and the frequency of rejection experiences. Although rejection experience always contains feelings of sadness, offense, and disappointment, the process helps a person transform with resilience, experience, and knowledge, leading to a positive outcome. Here are two quotes from the two participants’ pictures regarding positive reframing.

Although we are saddened by a rejection, turning the process into an advantage and continuing your way is necessary. As a result of these rejections, we begin to work better, like two arrows that hit the target one after the other. In other words, we are able to make better judgments (submission) with our lived experiences (P13, Fig. 10a).

I experience a short-term sadness upon receiving a manuscript rejection. However, I gather my strength using my own strategies and elevate my mood. I eliminate the reasons for my rejection as much as possible and prepare myself for a new submission (P19, Fig. 10b).

Regarding this strategy, another participant stated,

If the feedback is reasonable, I always think it helps me develop, and I make the necessary changes and continue working as usual. If there is no reason as to why I am rejected, I get outraged and go running to vent my rage. Of course, this is just a metaphor. What I mean is working harder and producing more. I mean, it is not much of a hindrance for me. Perhaps it is because I faced many obstacles throughout my career and had to overcome them. Thus, instead of wasting time on obstacles, I move on (P1).

This was a typical case among the participants (e.g., P1, P7, P11, P25, P23), which marked the significance of the reviewers’ feedback attached to the rejection.

Discussion and conclusion

The study aimed to illustrate the emotions related to manuscript rejection experiences and coping strategies. The findings based on the interview and photovoice methods indicated that desk rejections and peer review rejections caused negative emotions among the participants. We demonstrated that rejection-focused emotions varied based on their academic position (title), years of working experience, and the number of accepted papers. According to Bunner and Larson (2012), an author may be sad about being rejected but benefit from the constructiveness of reviewer comments. It can be attributed to the pain of rejection and that authors of the rejected manuscripts generally have much less publication experience. Put differently, rejection-focused emotion and its degree varied based on the participants’ characteristics.

The second part of the study explained the three coping strategies; avoidant strategies, neutral (neither approach nor avoidant) strategies, and approach strategies. Approach strategies consisted of acceptance, support, planning, and positive reframing, while avoidant strategies included denial, self-distraction, and venting. We also found that neutral strategies had humor as the only dimension (see Fig. 11). While our findings supported the existing studies on coping strategies, the difference in our research is that, as MacIntyre et al. (2020), the strategies for coping rejection were not precisely hierarchical as described in the studies on well-being, cancer, and grief. In other words, the participants who experienced manuscript rejection could prefer different coping strategies at different stages due to their lived experiences, personal characteristics, and being a responsible author. In coping with negative emotions, authors occasionally relied on “blame attribution” (co-author, reviewer, editor). This finding underlined blame attribution, as in many cases, rather than assuming responsibility (Arceneaux, 2003).

Rejection emotions and coping (figure inspired by Pandey et al., 2022)

The study’s novelty and significance lie in that emotions and coping with these emotions can be evaluated based on individuals’ expectations. In the literature, the expectation is rarely considered when evaluating the emotions and coping strategies associated with article rejection (e.g., Horn 2016). With this aspect, it is possible to assert that the study contributes. In fact, some participants with a high number of publications may perceive rejection as a reasonable or non-negative emotion, whereas those with high expectations for their studies may perceive it as the opposite. In the study, some authors with more than eleven WoS publications considered desk rejection reasonable, whereas others with similar or fewer publications considered desk rejection more destructive or negative. This can be interpreted to indicate that the outcome and the coping strategy to be applied may be related to the expectation. While the feedback or rejection received by an author who expects to receive feedback from a journal with a high rejection rate does not affect emotionally, another author with a high expectation of acceptance may experience negative emotions. For instance, authors who are rejected after multiple rounds of revision may feel more demoralized. The coping strategy used for this also differs, resulting in Feeling bad – attributed to others (Evans et al., 2008). On the other hand, authors who receive rejection in line with their expectations may exhibit behaviors suitable for seeking feedback (Fetzer, 2004), not taking the rejection personally, or positive about the future (Evans et al., 2008) coping strategies.

The present study has implications regarding understanding, interpreting, and managing academic failure among academics receiving a manuscript rejection. Although existing research has focused on academics’ negative experiences, our study highlighted rejection-focused emotions and coping strategies, often ignored in the literature. The relation between the failure of academic publishing for promotional purposes and coping strategies was significant, and when the expectation component was neglected, the study could add little to knowledge in the field. Nevertheless, this study provided important insights into many peoples’ publication experiences in academia. It depicted what the authors experiencing rejection thought about academic failure, how they approached and interpreted this experience, and what they did upon rejection. The findings illustrated that coping played a role in the rejection process and could impact individuals’ happiness, well-being, and self-esteem. This study also demonstrated that coping would significantly impact various outcomes, including the author’s mood, attitudes toward failure, and possibly the level of academic experience. We suggest some implications to help academics learn how to manage their actions actively or passively in terms of cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions to cope with failure in publishing. Many studies on coping with manuscript rejection have advised academics to perceive rejection as normal and redefine this process as a development opportunity (e.g., Nundy et al., 2022; Venketasubramanian & Hennerici, 2013).

On the other hand, the findings in this study can also inform the opposite side of the coin. First of all, the reviewers and editors who evaluate manuscripts have a chance to observe the experiences and perspectives of academics coping with rejection in more detail and with further depth. The study significantly contributes to both the reviewers’ and editors’ understanding of the perspectives of those who attribute failure (rejection), particularly to the review process and reviewers’ lack of expertise in evaluating the topic of manuscripts. The editorial group or other parties of the journals can take these findings as an opportunity to undertake precautions to prevent or explain misunderstandings. As Khadilkar (2018) advises, one should not be disappointed by rejection. When rejection rates are examined, about 80 of the 100 studies are destined to be rejected. Given this statistic, acknowledging the issue or the problem facilitates the coping process. The first and most important step in coping is staying calm, and avoiding responding to the rejection in a tantrum and acting emotionally, aggressively, or impulsively. Authors can turn a disadvantage into an advantage with a proper and impartial evaluation of the reasons for rejection and obtaining feedback on the rejection decision. Good authors learn and benefit from rejections for their future work. In addition, the success of an article seemed not to depend on initial rejections. For example, Furnham (2021) found that one of his papers rejected four times had over 500 citations, while his three best papers, in his view, did not even appear in the top 150 of his cited papers. This example indicates that articles accepted without rejection may not be successful.

This photovoice study, a community-based participatory research method, is novel and distinctive in methodology and theoretical perspective. This widely used policymaking method can also contribute to policymaking in terms of editorial and reviewing processes. The importance of the photovoice methodology in the study is that it can be evaluated based on the benefit it can provide that goes beyond individual benefits. Seeking to understand the coping strategies researchers employ significantly contributes to the perception that rejection is normal, particularly in the publication process. For instance, during a three-day scientific activity on academic writing, the first author of this study gave a presentation titled “the unbearable lightness of rejection” to approximately 150 participants who were primarily early-career researchers. At the end of the activity, feedback was obtained to confirm that the procedure should be considered normal.

Regarding the idea of policy making, the findings have important implications for university administrations or editorial boards’ policy-making process. The acceptance rates for journals indicate that many academics are destined to fail in publishing their work and receive rejections in their academic career. In this case, academics’ affiliated units or editorial boards can organize workshops or panels on how authors can manage and benefit from the rejection process. Considering the high possibility of failing to publish, academic institutions and editorial boards are advised to provide faculty members with resources not only when they fail but also on how to prepare for and cope with failure. Our findings can both inform the manuscript rejection processes and suggest potential implications or strategic examples that we can indirectly apply to other academic failures. According to Furnham (2021), publication pressure “seems to transcend disciplines and countries and tends to be more common at elite universities” (p. 843). Jaremka et al. (2020) suggest that focusing on individual-level solutions to help people cope with rejection cannot fully resolve the problem. Thus, we need a variety of measures at the institutional or stakeholder levels to help alter potentially toxic norms. Accordingly, Jaremka et al. (2020) highlight their suggested individual-level and structural/cultural changes.

As individuals often learn the best in their professional communities, professional institutions may also support researchers in coping with the negative emotions resulting from rejection. As many associations organize seminars or workshops to explain the approach to preparing a manuscript and the submission process, these meetings may also cover coping strategies. As it is known that professional training programs help individuals cope with difficult situations (Yip et al., 2008), professional communities, such as associations, can offer seminars and workshops to explain how rejections can be used to an academic’s advantage for improvement and to prepare participants for better preparation of manuscripts. Joint training programs between professional associations and higher education institutions that focus on evaluating manuscripts will also assist academics in engaging with the process to their advantage. In fact, academics can learn how to handle situations before they become stressful through participation in these activities.

Lastly, what distinguishes the specific coping strategies found in this study from those for other challenging life experiences (dealing, support strategies) is the potential to reach a better point than the initial one, especially through the approach strategies of acceptance, support, planning, and positive reframing. There are similarities and differences between the coping strategies used by individuals dealing with significantly more serious situations (such as rejection from the opposite sex, coping with cancer, social exclusion in the community, and coping with bereavement) and manuscript rejection. Compared to other psychologically challenging life experiences, active coping strategies are more likely to yield more effective results in article rejection.

Limitations and future studies

Since the study was conducted with a limited number of participants in a single country (Turkey), generalizability was a significant limitation, as in many qualitative studies. We recommend that future studies investigate rejection in different countries or cultures and explore how coping is considered in individualistic or collectivist cultures, which can provide a broad perspective on rejection. Other variables that this study do not consider, such as personality traits and self-control levels, can potentially help address the issue.

The themes explored in the study are restricted to the volunteer participants’ experiences. Another significant limitation was that our participants had articles published in WoS-indexed journals. Similar qualitative research conducted with academics without publications may produce different results. Besides, our participants had different academic titles. The study could suggest different results if the academic title was homogenous among the participants (e.g., assistant professor, doctorate students). One other limitation was our scope, in which coping with rejection diverged from many conventional topics. That is, academics who desire to pursue an academic career eventually have to accept the rejection process and continue their studies, making the topic of this study distinctive. It was impossible to reflect on the experiences and opinions of those who chose not to participate in the study, which may be a limitation.

We recommend focusing on quantitative research, using, for example, the COPE Inventory (Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced) for more generalizable results. Future studies can apply scales on rejection-focused emotions and coping strategies in many countries to contribute to obtaining comparative and generalizable results. Similarly, structural equation modeling (SEM), which can reveal the relationship between rejection-focused emotions and coping strategies and such dimensions as life satisfaction, well-being, and expectations, can help frame how a wider audience evaluates rejection more thoroughly.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Admiraal, W. F., Korthagen, F. A., & Wubbels, T. (2000). Effects of student teachers’ coping behaviour. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709900157958

Agah, N. N. (2019). Examining motivation theory in higher education among tenured and non-tenured faculty: Scholarly activity and academic rank (Doctoral dissertation, Fayetteville State University).

Anastas, J. W. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: issues and possible answers. Research on Social Work Practice, 14(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731503257870

Anderson, A. E., Hure, A. J., Kay-Lambkin, F. J., & Loxton, D. J. (2014). Women’s perceptions of information about alcohol use during pregnancy: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1048

Arceneaux, K. (2003). The conditional impact of blame attribution on the relationship between economic adversity and turnout. Political Research Quarterly, 56(1), 67–75.

Ashkar, P. J., & Kenny, D. T. (2008). Views from the inside: young offenders’ subjective experiences of incarceration. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 52(5), 584–597.

Barendregt, C. S., Van der Laan, A. M., Bongers, I. L., & Van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2015). Adolescents in secure residential care: the role of active and passive coping on general well-being and self-esteem. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(7), 845–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0629-5

Berk, B. (1977). Face-saving at the singles dance. Social Problems, 24(5), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.2307/800123

Booth, T., & Booth, W. (2003). In the frame: photovoice and mothers with learning difficulties. Disability & Society, 18(4), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759032000080986

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brown, G. K., & Nicassio, P. M. (1987). Development of a questionnaire for the assessment of active and passive coping strategies in chronic pain patients. Pain, 31(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(87)90006-6

Bunner, C., & Larson, E. L. (2012). Assessing the quality of the peer review process: author and editorial board member perspectives. American Journal of Infection Control, 40(8), 701–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2012.05.012

Burleson, B. R., & Goldsmith, D. J. (1996). How the comforting process works: Alleviating emotional distress through conversationally induced reappraisals. In Handbook of communication and emotion (pp. 245–280). Academic. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012057770-5/50011-4

Cluley, V. (2017). Using photovoice to include people with profound and multiple learning disabilities in inclusive research. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12174

Collingridge, D. S., & Gantt, E. E. (2008). The quality of qualitative research. American Journal of Medical Quality, 23(5), 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860608320646

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21.

Cox, A., & Benson, M. (2017). Visual methods and quality in information behaviour research: the cases of photovoice and mental mapping. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, 22(2), n2.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications.

Crocker, P. R., Kowalski, K. C., & Graham, T. R. (1998). Measurement of coping strategies in sport. In J. Duda (Ed.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement (pp. 149–161). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

Day, N. E. (2011). The silent majority: manuscript rejection and its impact on scholars. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(4), 704–718. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2010.0027

Driver, M. (2007). Reviewer feedback as discourse of the other: a psychoanalytic perspective on the manuscript review process. Journal of Management Inquiry, 16(4), 351–360.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, L., Cheung, C. M., Conboy, K., Duan, Y., Dubey, R., & Viglia, G. (2022). How to develop a quality research article and avoid a journal desk rejection. International Journal of Information Management, 62, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102426

Dohrenwend, B. S., Dohrenwend, B. P., Dodson, M., & Shrout, P. E. (1984). Symptoms, hassles, social supports, and life events: problem of confounded measures. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93(2), 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.93.2.222

Estes, B., & Polnick, B. (2012). Examining motivation theory in higher education: An expectancy theory analysis of tenured faculty productivity. International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration, 15 (1), 1–7.

Evans, T., Dobele, A., Hartley, N. S., & Benton, I. (2008). Academic rejection: the coping strategies of women. Studies in Learning, Evaluation, Innovation and Development (SLEID), 5(1), 34–45.

Fetzer, J. (2004). Dealing with reviews—the work of getting your paper accepted. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 379(3), 323–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-004-2608-z

Fielden, S. L., & Davidson, M. J. (1998). Social support during unemployment: are women managers getting a fair deal? Women in Management Review, 13(7), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649429810237123

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.1.150

Frambach, J. M., van der Vleuten, C. P., & Durning, S. J. (2013). AM last page: quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research. Academic Medicine, 88(4), 552. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f

Furnham, A. (2021). Publish or perish: rejection, scientometrics and academic success. Scientometrics, 126(1), 843–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03694-0

Graham, J. W., & Stablein, R. E. (1995). A funny thing happened on the way to publication: Newcomers’ perspectives on publishing in the organizational sciences. In L.L Cummings and P.J. Frost, (eds.) Publishing in the Organizational Sciences, (pp. 113-131). L.L. . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Gupta, V., Roy, H., & Sahu, G. (2021). HOW the tourism & hospitality lecturers coped with the transition to online teaching due to COVID-19: an assessment of stressors, negative sentiments & coping strategies. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 100341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100341

Hall, S. A., & Wilcox, A. J. (2007). The fate of epidemiologic manuscripts: a study of papers submitted to epidemiology. Epidemiology, 18(2), 262–265.

Holt, N. L., Hoar, S. D., & Fraser, S. (2005). Developmentally-based approaches to youth coping research: a review of literature. European Journal of Sports Sciences, 5(1), 25–39.

Horn, S. A. (2016). The social and psychological costs of peer review: stress and coping with manuscript rejection. Journal of Management Inquiry, 25(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492615586597

Jaremka, L. M., Ackerman, J. M., Gawronski, B., Rule, N. O., Sweeny, K., Tropp, L. R., & Vick, S. B. (2020). Common academic experiences no one talks about: repeated rejection, impostor syndrome, and burnout. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(3), 519–543.

Jurkowski, J. M. (2008). Photovoice as participatory action research tool for engaging people with intellectual disabilities in research and program development. Intellectual And Developmental Disabilities, 46(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2008)46[1:PAPART]2.0.CO;2

Kashdan, T. B., Barrios, V., Forsyth, J. P., & Steger, M. F. (2006). Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(9), 1301–1320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.003

Kaun, D. E. (1991). Writers die young: the impact of work and leisure on longevity. Journal of Economic Psychology, 12(2), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(91)90021-K

Khadilkar, S. S. (2018). Rejection blues: why do research papers get rejected? The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India, 68(4), 239–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-018-1153-1

Kim, S. D., Petru, M., Gielecki, J., & Loukas, M. (2019). Causes of manuscript rejection and how to handle a rejected manuscript. A Guide to the Scientific Career: Virtues, Communication, Research and Academic Writing, 419–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118907283.ch45

Kvale, S. (1994). Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications, Inc.

Latz, A. O. (2012). Toward a new conceptualization of photovoice: blending the photographic as method and self-reflection. Journal of Visual Literacy, 31(2), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2012.11674700

Lazarus, R. S. (2006). Stress and emotion: a new synthesis. Springer.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.