Abstract

University dropout represents a serious problem across the world. Past research has suggested the merits of studying both additive and multiplicative effects among the variables that affect the intention to drop out. In the present study, we tested the potential moderating effect of friendships at university, on both the association between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and intention to drop out and the associations between different motivations for attending university and intention to drop out. A sample of 404 Italian university students (Mage = 21.83; SD = 2.37) completed an online questionnaire. The outcomes showed that having friends at university was a protective factor in the relationship between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and intention to drop out. Students with a high number of university friends and low self-efficacy were less likely to intend to drop out than students with few university friends and low self-efficacy. Thus, having friends at university appears to protect students from developing the intention to drop out.

Similar content being viewed by others

The aims of the Europe 2020 strategy include increasing the percentage of students with a tertiary education by decreasing the rate of university dropout. To attain this goal, we need to advance our understanding of the processes and risk/protective factors implicated in students’ decision to abandon their university studies (Vossensteyn et al., 2015). According to the Sustainable Development Goals Report (Istat, 2019), Italy has the lowest percentage of graduates in Europe: only 28% of people aged 25–34 years hold a degree. As suggested by Heublein and Wolter (2011), students perceive university dropout as a personal failure with possible negative repercussions such as lower financial remuneration, worse job prospects, and fewer life opportunities. Thus, academic success in young adulthood appears to be a key developmental task that is tied up with the construction of identity and personal growth.

Previous research has investigated academic success by evaluating levels of “real dropout” and assessing academic persistence in terms of the length of time for which students are enrolled at university and their decision (where applicable) to give up their university studies (Robbins et al., 2004). As demonstrated by Respondek et al. (2017), early studies in this area displayed a key limitation: they were all conducted after dropout had occurred. In an effort to overcome this shortcoming, studies by Bean (1982) and Cabrera et al. (1993) investigated the intention to drop out of university and found it to be strongly related to—and predictive of—actual dropout rates. The intention to drop out of university is typically operationalized as comprising two aspects: (i) deliberation over whether or not to leave university; and (ii) discussion with parents, friends, or others about this issue. If universities can identify students who are thinking about withdrawing from university at an early stage (i.e., detect warning signs of dropout), they may be able to implement intervention programs to prevent students from following through with this intention (Morelli et al., 2021).

Previous research has suggested that there is an association between the intention to drop out of university and low academic grades (Allen et al., 2008; Bean, 1985). On the one hand, students who perform well academically may be more convinced that university was the right choice for them and feel more motivated to continue with their studies; on the other, students with poor academic performance may feel that their decision to attend university was misguided. Two of the main predictors of academic performance are self-efficacy and motivation. These same factors may also predict the intention to drop out of university.

Self-Regulated Learning Self-Efficacy

According to Bandura (1997) and social cognitive theory, self-efficacy is the belief that one can organize and effectively execute a series of actions to appropriately deal with new situations, trials, and challenges. Thus, low self-efficacy—rather than experiencing failure—is associated with a lack of belief in one’s own skills and abilities (Tak et al., 2017). From the perspective of social cognitive theory, people with high self-efficacy are more likely to view failure as a challenge and this may even strengthen their commitment to their goals. On the contrary, people with low self-efficacy may lose confidence in the face of failure, leading them to abandon the activity in question. In particular, self-regulated learning self-efficacy has been defined as the self-perceived ability to plan and organize one’s study time and activities, choose appropriate places to study, and ask for help when facing difficulty studying (Elias & MacDonald, 2007; Girelli et al., 2018; Komarraju & Nadler, 2013; Köseoğlu, 2015; Pajares, 1996). Self-regulated learning self-efficacy has been found to play a key role in school success (Alivernini & Lucidi, 2011; Caprara et al., 2011) and to mediate the relationship between external regulation and school achievement (Cattelino et al., 2019).

Meta-analyses (Robbins et al., 2004; Valentine et al., 2004) have confirmed the pivotal role of self-efficacy in predicting academic achievement and persistence, suggesting that students with good self-regulated learning self-efficacy are likely to deploy a range of self-regulatory learning strategies (e.g., self-monitoring, self-evaluation) that benefit their academic performance (Multon et al., 1991; Zimmerman, 2000). Consequently, students who perceive themselves as more capable and efficacious are more likely to complete their university studies, even if they meet challenges in the course of their college experience (Ojeda et al., 2011).

Motivation for Attending University

The process by which students decide to attend university is key to their retention and to the level of persistence that they display throughout their university studies (Girelli et al., 2018). A leading theoretical framework for understanding students’ motivation to attend university is self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2017). From this perspective, “humans are active, growth-oriented organisms, with an inherent tendency toward integrating experiences into a unified regulatory process” (Deci & Ryan, 2004, p. 433). Deci and Ryan (1985) distinguished between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, conceptualizing different motivational styles that vary according to subjects’ level of autonomy. Indeed, self-determination theory posits a continuum of self-determination, ranging from amotivation (i.e., the lowest level of self-determination and autonomy) to intrinsic motivation (i.e., the highest level of self-determination, which implies the deployment of autonomous regulation strategies). Altogether, as described by Girelli et al., (2018), there are five kinds of motivation along this continuum: (a) amotivation, defined as a total lack of interest in, and reasons for, attending university, which is typical of students with neither extrinsic nor intrinsic motivation, who demonstrate no personal sense of causation and who choose university because they do not know what else to do; (b) external motivation characterizing students whose decision to attend university is made, or forced upon them, by another person (e.g., a parent) and who are driven mainly by the desire to avoid punishment or negative consequences; (c) introjected motivation, which marks students whose decision to attend university is made in order to appear as capable as others (e.g., friends) and to feel proud of themselves, in an attempt to avoid guilt and anxiety and boost their ego and self-esteem; (d) identified motivation, which is a more autonomous and self-determined form of extrinsic motivation and characterizes students who decide to attend university because they are convinced of its importance for their future professional careers and personal growth; and finally (e) intrinsic motivation, the highest level of self-determination—associated with feelings of competence and autonomy—which is displayed by students who choose university on the basis of their interest and pleasure in studying a particular subject and discovering new knowledge within a specific domain, as well as on the sense of satisfaction they experience when studying (Van Herpen et al., 2017).

Numerous studies have found that self-determined motivation (i.e., intrinsic and autonomous motivation) to attend university is associated with greater academic achievement and student retention (Alivernini et al., 2016; Fan & Williams, 2018; Gillet et al., 2012; Girelli et al., 2018; Trevino & DeFreitas, 2014), while low self-determined motivation (i.e., amotivation, extrinsic regulation) is not (Ratelle et al., 2007). Litalien and Guay (2015) and Guiffrida et al. (2013) also reported that students with low intrinsic motivation more frequently intend to drop out of university, in contrast with students with high self-determined motivation, whose decision to attend university is based on their need for autonomy and who are more likely to perform well academically and less likely to intend to drop out. Furthermore, students who attend university for intrinsic and internal motivations rather than external reasons (such as to please parents and others) tend to be more academically competent and to achieve better academic outcomes (Kennett et al., 2013; Leontiev et al., 2020). Generally speaking, multiple studies across different countries and settings have contributed to shedding light on the role of self-determined motivation in developing and maintaining behavior that supports academic achievement (Deci et al., 2013; Girelli et al., 2016; Hagger & Chatzisarantis, 2016).

Social Relationships at University

Research has indicated that, in addition to individual and psychological aspects related to academic self-efficacy and motivation, good social relationships with peers at university is another key variable in academic success (Kutsyuruba et al., 2015). Even the first theoretical models of academic persistence and academic success by Tinto (1998) and Pascarella and Terenzini (2005) identified academic and social integration as leading factors in student well-being. Positive and supporting university environments are associated with stronger academic achievement (Abdullah et al., 2014; DeBerard et al., 2004; Lent et al., 2007; Mattanah et al., 2012; Yasin & Dzulkifli, 2011), and positive social relationships at university have been found to contribute to better university adjustment on the part of students (Duru, 2008; Lidy & Kahn, 2006; Schneider & Ward, 2003; Salami, 2011; Yusoff, 2012). These findings apply strongly in Italy, where the academic system requires students to attend class with the same group of peers for the entire day and the entire 3-year or 5-year duration of their degree course (Bonino & Cattelino, 2012).

A study by Mattanah et al. (2012) showed that university freshmen involved in social support group programmes felt less lonely and displayed higher levels of academic achievement. Isolated students, in contrast, reported a weaker sense of connection with their university peers and a lesser ability to use these relationships as capital; their academic performance was poorer and they were more likely to develop the intention to leave university. Therefore, positive relationships at university not only enhance adjustment, but also boost students’ academic performance. Furthermore, students with social relationships at university may find it easier to concentrate while studying and, when encountering difficulty, to ask for help and seek comfort; this may prevent them from developing the intention to leave university. Several studies have demonstrated that enjoying positive relationships with peers (Graham et al., 1992; Hagenauer & Volet, 2014) and perceiving themselves as academically integrated are factors that positively influence students’ growth and intellectual interest, thereby increasing their academic persistence and success (Berger & Milem, 1999; Schneider & Preckel, 2017). A recent study confirmed that having many relationships with classmates can protect high-school students with low self-efficacy due to poor school grades from developing depressive symptoms (Cattelino, Chirumbolo et al., 2021). Thus, peer relationships at school can function as a protective factor, moderating the relationship between school achievement and depressive symptoms, itself mediated by self-perceived efficacy in deploying self-regulation strategies. Another recent study found that having friends at university moderates the association between measures of self-determination and academic satisfaction (Morelli et al., 2021).

Aims and Hypotheses

Intention to drop out of university is associated with a history of uneven academic progress that reflects a problematic situation (Felice, 2005). It does not consist of a single event, but rather is the final phase in a dynamic, cumulative, and multifactorial process of student disengagement (De Witte et al., 2013; Lehr et al., 2003). It is important to investigate the factors influencing academic failure from a multivariate perspective (Ghione, 2005), in keeping with a recent review of the literature on school dropout (De Witte et al., 2013) which underscored the complex interaction among the numerous factors that contribute to academic success.

Research on academic success should consider multiple protective and risk factors, including individual, psychological, and relational factors (De Witte et al., 2013). Drawing on the theoretical frameworks of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997) and self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000), the aim of the present study was to investigate the role of self-regulated learning self-efficacy and the various kinds of motivation for attending university (i.e., amotivation, extrinsic motivation, external motivation, introjected motivation, identified motivation, and intrinsic motivation) in the intention to drop out of university, while controlling for the effect of students’ biological sex and age. It was expected that greater academic self-efficacy (Girelli et al., 2018; Valentine et al., 2004) and intrinsic motivation (as well as lower levels of amotivation) would be associated with a lesser likelihood of intending to drop out of university (Girelli et al., 2018; Guiffrida et al., 2013; Litalien & Guay, 2015).

Furthermore, as recommended by De Witte et al. (2013) and Bardach et al. (2019) based on their literature reviews, the present study was designed to offer an original analysis of both additive and multiplicative effects among the identified variables, in order to detect potential interactions among the factors implicated in academic failure. More specifically, we set out to investigate the possible moderating effect of friendships at university on the association between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and the intention to drop out, as well as on the respective associations between each kind of motivation (i.e., amotivation, extrinsic motivation, external motivation, introjected motivation, identified motivation, intrinsic motivation) and intention to drop out of university. We expected that having many friends at university would protect against the intention to drop out of university in students with low self-regulated learning self-efficacy and high amotivation or external motivation, in light of the known key role of social support during the university years (Cattelino, Chirumbolo et al., 2021; Lidy & Kahn, 2006; Mattanah et al., 2012). Indeed, self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) posits that the most strongly motivating activities are those that fulfil three basic needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Thus, precisely in situations where people experience low levels of intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy, having friends can act as a key protective factor against the tendency to withdraw. This is even more the case during adolescence and young adulthood, periods of development when friendships play a central role in individual wellbeing and choices (Arnett, 2015; Bagwell & Bukowski, 2018).

The moderating role of friendship is also consistent with the lifespan development model proposed by Hendry and Kloep (2002), which defines challenges as tasks or situations that require individuals to mobilize all their resources: even in the face of insufficient personal resources (in this case, low internal motivation and low self-efficacy), additional social resources (in this case, having friends at university) can help to address and overcome challenges, thereby reducing the risk of deterioration and withdrawal (in this case, the intention to drop out).

Method

Participants and Procedure

In order to determine the necessary sample size, we conducted an a priori power analysis, setting alpha was fixed at the conventional level of 0.05 and power at 0.80 (Cohen, 1988), and hypothesizing a small effect size (r = 0.20, Cohen, 1988). Given these parameters, the power analysis indicated a required minimum sample size of N = 194.

Participants were 404 students enrolled at Italian universities (age range = 18–30 years; M = 21.83; SD = 2.37; 84.7% female); 94.4% of participants (n = 407) were of Italian nationality. With regard to socio-economic status (SES), 308 (76.2%) reported that their families were of medium SES, while 114 (28.2%) reported a low personal SES and 261 (64.6%) a medium personal SES. Participants were attending different years of university: 89 (22%) were in their first year, 107 (26.5%) in their second year, 100 (24.8%) in their third year, 38 (9.4%) in their fourth year, and 40 (9.9%) in their fifth year, while 30 (n = 7.4%) were taking longer than the standard allotted period to complete their degree course. Finally, with regard to occupational status, 147 students (36.3%) reported working full- or part-time alongside their university studies, while the remaining 257 (63.6%) stated that they did not hold a job.

The researchers invited students to participate in the study via an email containing a link to the online survey. Recipients were asked to share the invitation with their friends by posting this link on their social networking platforms. Thus, we recruited participants via a snowball sampling procedure that spanned several Italian universities. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, each student provided informed consent on the first page of the online survey by clicking on the tab: “Yes, I agree to participate in the study.” The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sapienza University of Rome.

Measures

Socio-Demographic Information

Participants were asked to report selected demographic information, including: biological sex, age, nationality, family and personal SES, year and type of course/university attending, and occupational status.

Self-Regulated Learning Self-Efficacy

Students completed a modified version of the Multidimensional Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale (Bandura, 1990; Italian validated version by Pastorelli et al., 2001) so that their perceived self-regulated learning efficacy could be evaluated. The researchers adapted the 11-item scale ad hoc for the university students in the study. The scale is designed to assess students’ perceived ability to plan and organize their study time and activities, choose appropriate places to study, and ask for help when finding difficulty studying. Respondents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all capable) to 5 (totally capable). A sample item is: “How good are you at completing your exam revision on time?” In the present study, the scale displayed good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.83.

Motivation for Attending University

We investigated the students’ motivation for attending university via the Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire (A-SRQ; Ryan & Connell, 1989; Italian validated version by Alivernini & Lucidi, 2008; Girelli et al., 2018; Girelli et al., 2018), which asks students to consider why they decided to attend college. The instrument comprises 20 items to be rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (does not correspond at all) to 5 (corresponds exactly). Specifically, the questionnaire assesses five types of motivation to attend university: (1) amotivation, which is a total lack of interest in and reasons for attending university (four items; sample item: “I don’t know, for me it was a decision like any another”); (2) external motivation, which reflects a decision made by someone else, such as a parent (four items; sample item: “Someone else wants me to do it”); (3) identified motivation, or the perceived importance of a university education for one’s future professional career (four items; sample item: “Because I need it for what I want to do in life”); (4) intrinsic motivation, which links the decision to attend university to interest and pleasure in engaging in the chosen course of study (four items; sample item: “Because what we do on the degree course I am enrolled on is interesting to me”); and (5) introjected motivation, which attributes the decision to attend university to a perceived need to demonstrate capability and bolster one’s self-esteem (four items; sample item: “Because by completing this degree course, I can show what I am worth”). In the present study, the subscales for each of the five kinds of motivation displayed good reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.74 to 0.91.

Friendships at University

The researchers devised a single ad hoc item to measure the extent of the students’ circle of friends in the university setting. Specifically, respondents were asked to rate their number of friends at university on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (nobody) to 5 (6 or more friends). The instrument was designed to quantify friends (not simply classmates), given that intimacy and positive support are particularly characteristic of social relationships with friends (Rubin et al., 2006). Similar single-item measures have proved salient and informative in previous studies conducted with adolescents and young adults (Bonino et al., 2005; Jessor, 2016; Morelli et al., 2021).

Intention to Drop out of University

The researchers devised a six-item scale to measure intention to drop out of university based on an earlier-developed measure by Bonino et al. (2005). A sample item is: “Have you ever talked seriously with your parents (or anybody else) about leaving university?” Respondents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The instrument displayed good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.89.

Data Analysis

We conducted correlational analyses among all the study variables. Subsequently, we performed a series of moderated regression analyses to test the moderating effect of friendships at university on both the association between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and intention to drop out of university and the associations between the various kinds of motivation to attend college (i.e., amotivation, external motivation, intrinsic motivation, identified motivation, introjected motivation) and intention to drop out, while controlling for students’ biological sex and age. We ran slopes analyses to shed further light on the direction of the interactions. We converted the raw scores for all variables into z-scores in order to completely standardize the data set (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

Correlations Among Variables

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for all the study variables are reported in Table 1. Intention to drop out of university was significantly positively correlated with age, amotivation, external motivation, and introjected motivation; and significantly negatively correlated with self-regulated learning self-efficacy, identified motivation, intrinsic motivation, and friendships at university.

Moderated Regression Analyses

We ran a series of moderated regression analyses to test for potential moderating effects of friendships at university on the association between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and intention to drop out of university, and on the associations between each of the different kinds of motivation to attend university (i.e., amotivation, external motivation, intrinsic motivation, identified motivation, introjected motivation) and intention to drop out, while controlling for students’ biological sex and age. We found that age, b = 0.09, p = 0.03, self-regulated learning self-efficacy, b = -0.15, p = 0.003, amotivation, b = 0.27, p < 0.001, identified motivation, b = -0.21, p < 0.001, and the interaction between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and friendships at the university, b = 0.10, p = 0.03, were significant predictors of intention to drop out, accounting for 33% of variance, R = 0.57, p < 0.001. All the outcomes of the final model are reported in Table 2.

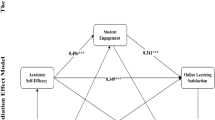

To shed further light on the direction of the interactions, we conducted a set of simple slopes analyses, plotting the predicted values of intention to drop out of university as a function of self-regulated learning self-efficacy and three different levels of the moderator variable (i.e., friendships at university; see Fig. 1). In slopes analysis, a low score on the moderator variable is conventionally set at one standard deviation below the mean (-1 SD), a high score at one standard deviation above the mean (+ 1 SD), and a medium score at the mean itself (Aiken & West, 1991). In our case, a low number of friendships at university was associated with a significant negative relationship between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and intention to drop out of university, b = -0.24, t = -3.90, p < 0.001. At the mean number of friendships at university, the main effect of self-regulated learning self-efficacy on intention to drop out of university was b = -0.15, t = -3.04, p = 0.003. When a high number of friendships at university was reported, the relationship between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and intention to drop out of university became weaker and non-significant, b = -0.07, t = -1.05, p = 0.29. Thus, friendships at university conditioned the impact of self-regulated learning self-efficacy on intention to drop out of university. More specifically, having many friends in their university environment appeared to protect students with low self-regulated learning self-efficacy from developing the intention to drop out (see Fig. 1). On the contrary, having few friends at college appeared to represent a risk factor for students with low self-regulated learning self-efficacy, who were more likely to develop the intention to withdraw from their university course.

Discussion

University dropout is a serious problem all over the world. A report by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2020) showed that only 28% of Italian and 49.4% of American students aged 25–34 have completed third-level education. Given the gravity of the phenomenon, there is an urgent need for research investigating and identifying the factors that influence university dropout, so that effective preventive interventions can be implemented. Defeating university dropout by increasing the number of students who are able to complete tertiary education is key to individual well-being over the long term, given that a low level of education can be an obstacle to social and work inclusion and life satisfaction (Heublein & Wolter, 2011).

Raising the rate of students completing tertiary education requires strategies that aim at, on the one hand, increasing the number of students enrolled at university and, on the other hand, reducing the number of dropouts. The present study was focused on the second of these aspects, investigating factors that may help students to complete their university studies and thereby prevent them from developing the intention to drop out.

As brought to light by previous studies (De Witte et al., 2013; Lehr et al., 2003), factors that foster academic persistence and mitigate university dropout need to be analysed from a complex and multifactorial perspective that takes into account both individual and contextual variables. Indeed, the intention to drop out of university can stem from the complex interaction of multiple factors. The present findings confirm that key individual factors that protect against developing the intention to drop out of university are self-regulated learning self-efficacy, identified motivation, and the absence of amotivation. These results are in line with previously reported research evidence (Girelli et al., 2016; Ratelle et al., 2007; Robbins et al., 2004), which suggests that students who perceive themselves as able to control their study practices, and who are motivated to engage in their university studies mainly because they think that doing so is important for their future careers and personal growth, are less inclined to drop out.

The added value of the present research is its consideration of the possible moderating effect of having friends at university on the relationship between individual variables (i.e., self-regulated learning self-efficacy and different kinds of motivation for attending university) and the intention to drop out. Attending university is a key developmental task and personal growth challenge for young adults. Thus, it can be particularly meaningful for students to face the more demanding aspects of their university studies alongside friends within a shared environment, and this can protect them from developing academic disengagement (Brint & Cantwell, 2014) and the intention to drop out (Yasin & Dzulkifli, 2011). More specifically, the moderated regression analyses in this study showed that having friends at university can wield a protective effect on the relationship between self-regulated learning self-efficacy and intention to drop out of university. Students with many friends at university and low self-regulated learning self-efficacy were less likely to report the intention to drop out. Conversely, students with few friends at university and low self-regulated learning self-efficacy were more likely to have thoughts of dropping out. Thus, having friends in one’s university environment appears to be a key protective factor against university dropout. In keeping with this finding, previous studies have shown that social support can mitigate stress (Pauley & Hesse, 2009; Wright, 2012), help students to cope with academic challenges (Thompson, 2008), and motivate them to learn (Jones, 2008). These results are also in keeping with self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), which highlights the key contribution of fulfilling the need for relatedness to fostering engagement and retention: particularly in situations where other needs, such as competence, are not satisfied, intimate relationships, such as friendship, can the propensity to give up an activity. Finally, based on the lifespan development model (Hendry & Kloep, 2002), it might be argued that when personal resources, such as self-efficacy, are scarce, social resources, such as having many friends at university, can help students to cope with and overcome challenges by reducing their risk of developing the intention to drop out.

Positive academic relationships may help students to develop a sense of belonging, which in turn protects them from feelings of loneliness (Davis et al., 2019), a common experience among university students (Limarutti et al., 2021), especially during their first year, and a phenomenon that can negatively impact student retention (Schneider & Preckel, 2017). The present study is of particular salience to the Italian (Felice, 2005) and other cultural contexts where peer relations are not actively encouraged at many universities and university dropout is mainly countered via individual cognitive-motivational interventions (Girelli et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, the study presents some limitations. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, it is not possible to infer causal relationships among the variables. Future longitudinal studies are required to improve our understanding of how protective and risk factors in academic success co-evolve over time. Furthermore, the participants did not comprise a representative sample of the general population of university students; thus, the generalizability of the results is limited. However, the size and direction of the identified relationships were theoretically plausible and empirically similar to those reported in the literature. Thus, the lack of sample representativeness is not likely to be a major limitation of the study. Finally, friendships were measured via a single item asking respondents to rate the number of friends they had in their university environment. While this is a salient and informative item (Bonino et al, 2005; Jessor, 2016), future studies should go on to investigate which specific characteristics of friendship (e.g., help, sharing, support, or intimacy) are most effective in combating the intention to drop out, especially in individuals with poor self-efficacy.

Despite the shortcomings just outlined, the present study can usefully inform the development and implementation of effective prevention programs and interventions aimed at reducing academic failure and dropout, thus promoting academic well-being among students. The findings suggest that intervention and prevention programs should focus not only on enhancing student performance but also on creating a context in which students can establish positive relationships with their peers (Bronkema, & Bowman, 2019). Indeed, universities should foster and sustain academic integration and social relationships among students by setting up and enhancing group activities and communal meeting places for students, especially in contexts lacking campus facilities. In attempting to reduce university dropout, it is important not only to boost students’ self-efficacy (Zimmerman, 2000), but also to construct university environments that offer opportunities for students to meet and interact with peers, thereby forming new friendships (Morelli et al., 2021). Thus, intervention and prevention programs should be aimed at impacting both the individual and social/contextual levels. To this end, universities might consider inviting all undergraduates to participate in the annual opening ceremony, especially the first-year students; indeed, this type of event can function as a bonding ritual that fosters student’ sense of belonging to the university institution. Colleges should also encourage cultural, recreational, and sports activities and events outside of class time, and the setting up of common study areas on campus, with a view to helping students overcome the loneliness and “homesickness” that are often a feature of attending university and to preventing student disengagement (Chipchase et al., 2017).

Previous research has suggested the importance of peer tutoring (Da Re & Riva, 2018; Griffin & Griffin, 1997); indeed, peer tutors can be particularly effective in helping students to manage difficulties, for example by suggesting strategies and tips for coping with exams. Symmetrical and balanced relationships, such as those with peer tutors, can be of great assistance for students who find it difficult to ask for help. Assigning peer tutors could contribute to enhancing students’ academic self-efficacy, given that tutors can increase students’ self-perceived ability to organize and manage shared university challenges. Enhancing both students’ self-regulated learning self-efficacy and their social relationships at university could contribute significantly to reducing academic failure.

Finally, in terms of more classical interventions aimed at enhancing academic self-efficacy, teachers might encourage the formation of study groups among students, because self-efficacy and academic success can also be enhanced by exchanges with and reinforcement from peers more generally (Bandura, 1997). Participating in study groups, alongside other social activities, may help students to develop more realistic perceptions of their own study skills, thus protecting them from academic disengagement, isolation, and depression, which are commonly experienced during the university years (Cattelino, Chirumbolo et al., 2021; Cattelino, Testa et al., 2021, 2020, 2021; Nelson et al., 2012). Furthermore, this kind of intervention may not only affect individual students, but also the university social environment, by providing new opportunities for students to form friendships with their peers.

Finally, the present findings bear some clear research implications. Future studies should investigate which aspects of friendship (e.g., support, intimacy) are most salient to preventing dropout and also how social support more broadly (i.e., beyond having friends at university) might play a role in enhancing academic persistence.

Data availability

Data are available under request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abdullah, M. C., Kong, L. L., & Talib, A. R. (2014). Perceived social support as predictor of university adjustment and academic achievement amongst first year undergraduates in a Malaysian Public university. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 11, 59–73.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage.

Alivernini, F., & Lucidi, F. (2008). The Academic Motivation Scale (AMS): Factorial structure, invariance and validity in the Italian context. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 15(4), 211–220.

Alivernini, F., & Lucidi, F. (2011). Relationship between social context, self-efficacy, motivation, academic achievement, and intention to drop out of high school: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Educational Research, 104, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671003728062

Alivernini, F., Manganelli, S., & Lucidi, F. (2016). The last shall be the first: Competencies, equity and the power of resilience in the Italian school system. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.08.010

Allen, J., Robbins, S. B., Casillas, A., & Oh, I. S. (2008). Third-year college retention and transfer: Effects of academic performance, motivation, and social connectedness. Research in Higher Education, 49, 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9098

Arnett, J. J. (Ed.). (2015). The Oxford handbook of emerging adulthood. Oxford University Press.

Bagwell, C. L., & Bukowski, W. M. (2018). Friendship in childhood and adolescence: Features, effects, and processes. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 371–390). The Guilford Press.

Bandura, A. (1990). Multidimensional scales of perceived academic efficacy. Stanford University.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Bardach, L., Lüftenegger, M., Oczlon, S., Spiel, C., & Schober, B. (2019). Context-related problems and university students’ dropout intentions—the buffering effect of personal best goals. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-019-00433-

Bean, J. P. (1982). Student attrition, intentions, and confidence: Interaction effects in a path model. Research in Higher Education, 17(4), 291–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00977899

Bean, J. P. (1985). Interaction effects based on class level in an explanatory model of college student dropout syndrome. American Educational Research Journal, 22(1), 35–64. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312022001035

Berger, J. B., & Milem, J. F. (1999). The role of student involvement and perceptions of integration in a causal model of student persistence. Research in Higher Education, 40(6), 641–664. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018708813711

Bonino S., & Cattelino E. (2012). “Italy”. In Jeffrey Jensen Arnett Adolescent psychology around the world. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 290-305.

Bonino, S., Cattelino, E., & Ciairano, S., (2005). Adolescents and risk. Behaviors, functions and protective factors. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag.

Brint, S., & Cantwell, A. M. (2014). Conceptualizing, measuring, and analyzing the characteristics of academically disengaged students: Results from UCUES 2010. Journal of College Student Development, 55(8), 808–823. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2014.0080

Bronkema, R. H., & Bowman, N. A. (2019). Close campus friendships and college student success. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 21(3), 270–285.

Cabrera, A. F., Nora, A., & Castaneda, M. B. (1993). College persistence: Structural equa-tions modeling test of an integrated model of student retention. The Journal of Higher Education, 64, 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1993.11778419

Caprara, G. V., Vecchione, M., Alessandri, G., Gerbino, M., & Barbaranelli, C. (2011). The contribution of personality traits and self-efficacy beliefs to academic achievement: A longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(1), 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1348/2044-8279.002004

Cattelino, E., Morelli, M., Baiocco, R., & Chirumbolo, A. (2019). From external regulation to school achievement: The mediation of self-efficacy at school. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 60, 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2018.09.007

Cattelino E., Testa S., Calandri E., Fedi A., Gattino S., Graziano F., Rollero C., Begotti T. (2021). Self-efficacy, subjective well-being and positive coping in adolescents with regards to Covid-19 lockdown. Current Psychology, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01965-4

Cattelino, E., Chirumbolo, A., Calandri, E., Baiocco, R., & Morelli, M. (2021). School achievement and depressive symptoms in adolescence: The role of self-efficacy and peer relationships at school. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01043-z

Chipchase, L., Davidson, M., Blackstock, F., Bye, R., Clothier, P., Klupp, N., ... & Williams, M. (2017). Conceptualising and measuring student disengagement in higher education: A synthesis of the literature. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(2), 31-42.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Davis, G. M., Hanzsek-Brill, M. B., Petzold, M. C., & Robinson, D. H. (2019). Students’ sense of belonging: The development of a predictive retention model. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 19(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v19i1.26787

De Witte, K., Cabus, S., Thyssen, G., Groot, W., & van den Brink, H. M. (2013). A critical review of the literature on school dropout. Educational Research Review, 10, 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.002

DeBerard, M. S., Spielmans, G. I., & Julka, D. L. (2004). Predictors of academic achievement and retention among college freshmen: A longitudinal study. College Student Journal, 38(1), 66–81.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The" what" and" why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., & Guay, F. (2013). Self-determination theory and actualization of human potential. In D. McInerney, H. Marsh, R. Craven, & F. Guay (Eds.), Theory Driving Research: New Wave Perspectives on Self Processes and Human Development (pp. 109–133). Information Age Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of self-determination research. University Rochester Press.

Duru, E. (2008). The predictive analysis of adjustment difficulties from loneliness, social support, and social connectedness. Educational Sciences: Theories & Practice, 8(3), 849–856.

Elias, S. M., & MacDonald, S. (2007). Using past performance, proxy efficacy, and academic self-efficacy to predict college performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 2518–2531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00268.x

Fan, W., & Williams, C. (2018). The mediating role of student motivation in the linking of perceived school climate and achievement in reading and mathematics. Frontiers in Education, 3(50), https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00050

Felice, A. (2005). L'accompagnamento per contrastare la dispersione universitaria: mentoring e tutoring a sostegno degli studenti. [Accompaniment to counter university dispersion: mentoring and tutoring in support of students]. Retrieved from http://isfoloa.isfol.it/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/1524/Isfol_FSE68.pdf?sequence=1

Ghione, V. (2005). La dispersione scolastica. Le parole chiave. [Early school leaving. The keywords]. Roma: Carocci.

Gillet, N., Berjot, S., Vallerand, R. J., & Amoura, S. (2012). The role of autonomy support and motivation in the prediction of interest and dropout intentions in sport and education settings. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34(3), 278–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.674754

Girelli, L., Hagger, M., Mallia, L., & Lucidi, F. (2016). From perceived autonomy support to intentional behaviour: Testing an integrated model in three healthy eating behaviours. Appetite, 96, 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.027

Girelli, L., Alivernini, F., Lucidi, F., Cozzolino, M., Savarese, G., Sibilio, M., & Salvatore, S. (2018). Autonomy supportive contexts, autonomous motivation, and self-efficacy predict academic adjustment of first-year university students. Frontiers in Education, 3(95), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00095

Graham, E. E., West, R., & Schaller, K. A. (1992). The association between the relational teaching approach and teacher job satisfaction. Communication Reports, 5(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934219209367539

Griffin, B. W., & Griffin, M. M. (1997). The effects of reciprocal peer tutoring on graduate students’ achievement, test anxiety, and academic self-efficacy. The Journal of Experimental Education, 65(3), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1997.9943454

Guiffrida, D. A., Lynch, M. F., Wall, A. F., & Abel, D. S. (2013). Do reasons for attending college affect academic outcomes? A test of a motivational model from a self-determination theory perspective. Journal of College Student Development, 54, 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2013.0019

Hagenauer, G., & Volet, S. E. (2014). Teacher–student relationship at university: An important yet under-researched field. Oxford Review of Education, 40(3), 370–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.921613

Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2016). The trans-contextual model of autonomous motivation in education: Conceptual and empirical issues and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 360–407. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315585005

Hendry, L.B., & Kloep, M. (2002). Lifespan development. Resources, challenges and risks. London: Thomson Learning.

Heublein, U., & Wolter, A. (2011). Studienabbruch in Deutschland: Definition, Häufigkeit, Ursachen, Maßnahmen [Dropout in Germany: Definition, Frequency, Cause, Interventions]. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik, 57, 214–236.

Jessor R. (2016). The Origins and Development of Problem Behavior Theory. The Collected Works of Richard Jessor. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40886-6

Jones, A. C. (2008). The effects of out-of-class support on student satisfaction and motivation to learn. Communication Education, 57(3), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520801968830

Kennett, D. J., Reed, M. J., & Stuart, A. S. (2013). The impact of reasons for attending university on academic resourcefulness and adjustment. Active Learning in Higher Education, 14, 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787413481130

Komarraju, M., & Nadler, D. (2013). Self-efficacy and academic achievement: Why do implicit beliefs, goals, and effort regulation matter?. Learning and Individual Differences, 25, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.01.005

Köseoğlu, Y. (2015). Self-efficacy and academic achievement – A case from Turkey. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(29), 131–141.

Kutsyuruba, B., Klinger, D. A., & Hussain, A. (2015). Relationships among school climate, school safety, and student achievement and well-being: A review of the literature. Review of Education, 3(2), 103–135.

Lehr, C. A., Hansen, A., Sinclair, M. F., & Christenson, S. L. (2003). Moving beyond dropout towards school completion: An integrative review of data-based interventions. School Psychology Review, 32(3), 342–365.

Lent, R. W., Singley, D., Sheu, H. B., Schmidt, J. A., & Schmidt, L. C. (2007). Relation of social-cognitive factors to academic satisfaction in engineering students. Journal of Career Assessment, 15(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072706294518

Leontiev, D. A., Osin, E. N., Fam, A. K., & Ovchinnikova, E. Y. (2020). How you choose is as important as what you choose: Subjective quality of choice predicts well-being and academic performance. Current Psychology, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01124-1

Lidy, K. M., & Kahn, J. H. (2006). Personality as a predictor of first-semester adjustment to college: The mediational role of perceived social support. Journal of College Counseling, 9(2), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2006.tb00099.x

Limarutti, A., Maier, M. J., & Mir, E. (2021). Exploring loneliness and students’ sense of coherence (S-SoC) in the university setting. Current Psychology, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02016-8

Litalien, D., & Guay, F. (2015). Dropout intentions in PhD studies: A comprehensive model based on interpersonal relationships and motivational resources. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.004

Mattanah, J. F., Brooks, L. J., Brand, B. L., Quimby, J. L., & Ayers, J. F. (2012). A social support intervention and academic achievement in college: Does perceived loneliness mediate the relationship? Journal of College Counseling, 15(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00003.x

Morelli, M., Chirumbolo, A., Baiocco, R., & Cattelino, E. (2021). Academic failure: Individual, organizational, and social factors. Psicología Educativa, 27(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a8

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(1), 30–38.

Nelson, K. J., Quinn, C., Marringron, A., & Clarke, J. A. (2012). Good practice for enhancing the engagement and success of commencing students. Higher Education, 63, 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9426-y

OECD (2020). Population with tertiary education (indicator). Retrieved from https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/population-with-tertiary-education.html. https://doi.org/10.1787/0b8f90e9-en

Ojeda, L., Flores, L. Y., & Navarro, R. L. (2011). Social cognitive predictors of Mexican American college students’ academic and life satisfaction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021687

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 543–578. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066004543

Pascarella, E., & Terenzini, P. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research. Wiley.

Pastorelli, C., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Rola, J., Rozsa, S., & Bandura, A. (2001). The structure of children’s perceived self-efficacy: A cross-national study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 17(2), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.17.2.87

Pauley, P. M., & Hesse, C. (2009). The effects of social support, depression, and stress on drinking behaviors in a college student sample. Communication Studies, 60(5), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970903260335

Ratelle, C. F., Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., Larose, S., & Senécal, C. (2007). Autonomous, controlled, and amotivated types of academic motivation: A person-oriented analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(4), 734–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.734

Da Re, L., & Riva, C. (2018). Favorire il successo accademico con il Tutorato Formativo. L'esperienza del Corso di Laurea in Scienze Sociologiche dell'Università di Padova. [Encouraging academic success with the Training Tutorship. The experience of the Degree Course in Sociological Sciences of the University of Padua.], Scuola Democratica, 9(2), 271–290. 12828/90562

Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Stupnisky, R., & Nett, U. E. (2017). Perceived academic control and academic emotions predict undergraduate university student success: Examining effects on dropout intention and achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(243), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00243

Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.261

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. Social, emotional, and personality developmentIn W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 571–645). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749–761. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.749

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

Salami, S. O. (2011). Psychosocial predictors of adjustment among first year college of education students. US-China Education Review, 8(2), 239–248.

Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2017). Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 143(6), 565–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000098

Schneider, M. E., & Ward, D. J. (2003). The role of ethnic identification and perceived social support in Latinos’ adjustment to college. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25(4), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986303259306

Tak, Y. R., Brunwasser, S. M., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., & Engels, R. C. (2017). The prospective associations between self-efficacy and depressive symptoms from early to middle adolescence: A cross-lagged model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 744–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0614-z

Thompson, B. (2008). How college freshmen communicate student academic support: A grounded theory study. Communication Education, 57(1), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520701576147

Tinto, V. (1998). Colleges as communities: Taking research on student persistence seriously. Review of Higher Education, 21, 167–177. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/30046.

Trevino, N. N., & DeFreitas, S. C. (2014). The relationship between intrinsic motivation and academic achievement for first generation Latino college students. Social Psychology of Education, 17(2), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-013-9245-3

Valentine, J. C., DuBois, D. L., & Cooper, H. (2004). The relation between self-beliefs and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_3

van Herpen, S. G. A., Meeuwisse, M., Hofman, W. H. A., Severiens, S. E., & Arends, L. R. (2017). Early predictors of first-year academic success at university: Pre-university effort, pre-university self-efficacy, and pre-university reasons for attending university. Educational Research and Evaluation, 23(1–2), 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2017.1301261

Vossensteyn, J. J., Kottmann, A., Jongbloed, B. W. A., Kaiser, F., Cremonini, L., Stensaker, B., ... & Wollscheid, S. (2015). Dropout and completion in higher education in Europe: main report. European Union. https://doi.org/10.2766/826962

Wright, K. B. (2012). Emotional support and perceived stress among college students using Facebook.com: An exploration of the relationship between source perceptions and emotional support. Communication Research Reports, 29(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2012.695957

Yasin, A. S. M., & Dzulkifli, M. A. (2011). The relationship between social support and academic achievement. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(5), 277–281.

Yusoff, Y. M. (2012). Self-efficacy, perceived social support, and psychological adjustment in international undergraduate students in a public higher education institution in Malaysia. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(4), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311408914

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the ethic committee of University (blinded for peer review).

Consent to Participate

Each participant gave his/her consent to participate in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morelli, M., Chirumbolo, A., Baiocco, R. et al. Self-regulated learning self-efficacy, motivation, and intention to drop-out: The moderating role of friendships at University. Curr Psychol 42, 15589–15599 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02834-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02834-4