Abstract

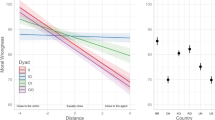

We tested whether moral judgments in a cross-cultural setting are related to both culture and moral foundations. Our objective was to verify if the relationship between cultural power distance and moral judgment of both egoistic and other-oriented lies told to one’s supervisor is mediated by adherence to the ethics of authority. We analyzed data from Mexican, Spanish, Estonian, Dutch, Swedish, and Polish respondents (N = 1176). The hypothesized mediation effects were found to be significant: higher power distance entailed more negative moral judgments. Power distance was positively related to the ethics of authority, which was in turn related to harsher moral judgments. When we controlled for the influence of the ethics of authority, power distance was no longer related to moral judgments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The entire project was conducted on 1482 participants. However, in the first part of the project we showed that egoistic lies regarding professional and private life merged into one factor in Ireland (Cantarero et al. 2018). To be able to better answer the research question for the second part of the project described in this paper, we excluded data from Ireland in the analysis, which resulted in the analyzed sample consisting of 1176 participants.

References

Aune, R. K., & Waters, L. L. (1994). Cultural differences in deception: Motivations to deceit in Samoans and North Americans. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18(2), 159–172.

Autio, E., Pathak, S., & Wennberg, K. (2013). Consequences of cultural practices for entrepreneurial behaviors. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(4), 334–362.

Auzoult, L., Abdellaoui, S., & Gangloff, B. (2015). L’impact des distances psychologiques et des valeurs de distances de pouvoir sur le jugement socio-moral vis-ŕ-vis de transgressions et de conduites atypiques en milieu professionnel. Psychologie du Travail et des Organisations, 21, 380–394.

Bame-Aldred, C. W., Cullen, J. B., Martin, K. D., & Parboteeah, K. P. (2013). National culture and firm-level tax evasion. Journal of Business Research, 66(3), 390–396.

Bessarabova, E. (2014). The effects of culture and situational features on in-group favoritism manifested as deception. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 39, 9–21.

Bobbio, A., Nencini, A., & Sarrica, M. (2011). Il moral foundation questionnaire: Analisi della struttura fattoriale della versione Italiana. Giornale di Psicologia, 5, 7–18.

Cantarero, K., Szarota, P., Stamkou, E., Navas, M., & Dominguez Espinosa, A. (2018).When is a lie acceptable? Work and private life lying acceptance depends on its beneficiary. The Journal of Social Psychology ,158(2), 220–235.

Carl, D., Gupta, V., & Javidan, M. (2004). Power distance. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 513–563). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Clifford, S. (2017). Individual differences in group loyalty predict partisan strength. Political Behavior, 39(3), 531–552.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 98–104.

DePaulo, B. M., Kashy, D. A., Kirkendol, S. E., Wyer, M. M., & Epstein, J. A. (1996). Lying in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(5), 979–995.

Dunleavy, K. N., Chory, R. M., & Goodboy, A. K. (2010). Responses to deception in the workplace: Perceptions of credibility, power and trustworthiness. Communication Studies, 61, 239–255.

Fu, G., Xu, F., Cameron, C. A., Heyman, G., & Lee, K. (2007). Cross-cultural differences in children’s choices, categorizations, and evaluations of truths and lies. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 278–293.

Gold, N., Colman, A. M., & Pulford, B. D. (2014). Cultural differences in responses to real-life and hypothetical trolley problems. Judgment and Decision Making, 9(1), 65–76.

Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2013). Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 55–130.

Grover, S. L., & Hui, C. (2005). How job pressures and extrinsic rewards affect lying behavior. The International Journal of Conflict Management, 16(3), 287–300.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Haidt, J. (2013). The righteous mind. Why good people are divided by politics and religion. London: Penguin Books.

Haidt, J., & Bjorklund, F. (2008). Social intuitionists answer six questions about moral psychology. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Moral psychology, volume 2. The cognitive science of morality: Intuition and diversity (pp. 181–219). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20, 98–116.

Haidt, J., & Hersh, M. A. (2001). Sexual morality: The cultures and emotions of conservatives and liberals. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(1), 191–221.

Haidt, J., Koller, S. H., & Dias, M. G. (1993). Affect, culture and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 613–628.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications.

Ho, Y. H., & Lin, C. Y. (2016). The moral judgment relationship between leaders and followers: A comparative study across the Taiwan Strait. Journal of Business Ethics, 134, 299–310.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hox, J. J. (1998). Multilevel modeling: When and why. In I. Balderjahn, R. Mathar, & M. Schader (Eds.), Classification, data analysis and data highways (pp. 147–154). New York: Springer.

Indvik, J., & Johnson, P. (2009). Liar! Liar! Your pants are on fire: Deceptive communication in the workplace. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications, and Conflict, 13(1), 1–8.

Iyer, R., Spassena, K. P., Graham, J., Ditto, P. H., & Haidt, J. (2012). Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological roots of an individualist ideology. PLoS One, 7(8), e42366. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042366.

Laham, S. M., Chopra, S., Lalljee, M., & Parkinson, B. (2010). Emotional and behavioral reactions to moral transgressions: Cross-cultural and individual variations in India and Britain. International Journal of Psychology, 45(1), 64–71.

Matsumoto, D., & Yoo, H. S. (2006). Toward a new generation of cross-cultural research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(3), 234–250.

Mealy, M., Stephen, W., & Urrutia, C. I. (2007). The acceptability of lies: A comparison of Ecuadorians and euro-Americans. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31, 689–702.

Richter, T. (2006). What is wrong with ANOVA and multiple regression? Analyzing sentence reading times with hierarchical linear models. Discourse Processes, 41, 221–250.

Rodriguez, J. I. (1997). Deceptive communication from collectivistic and individualistic perspectives. Intercultural Communication Studies, 6(2), 111–118.

Seiter, J. S., Bruschke, J., & Bai, C. (2002). The acceptability of deception as a function of perceivers’ culture, deceiver’s intention and deceiver-deceived relationship. Western Journal of Communication, 66(2), 158–180.

Shweder, R. A. (1990). In defense of moral realism: Reply to Gabennesch. Child Development, 61, 2060–2067.

Sims, R. L. (2000). The relationship between employee attitudes and conflicting expectations for lying behavior. The Journal of Psychology, 134(6), 619–633.

Smith, P. B. (2002). Levels of analysis in cross-cultural psychology. In W. J. Lonner, D. L. Dinnel, S. A. Hayes, & D. N. Sattler (Eds.), Online readings in psychology and culture (unit 2, chapter 7), Center for cross-cultural research (Vol. 2). Bellingham: Western Washington University.

Stedham, Y., & Beekun, R. I. (2013). Ethical judgment in business: Culture and differential perceptions of justice among Italians and Germans. Business Ethics, 22, 189–201.

Van Leeuwen, F., Park, J. H., Koening, B. L., & Graham, J. (2012). Regional variation in pathogen prevalence predicts endorsement of group-focused moral concerns. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(5), 429–437.

Acknowledgements

This project was conducted thanks to research grant awarded to Katarzyna Cantarero by the National Science Centre in Poland. The grant title was ‘Cross-cultural differences in the acceptance of lying in view of the Moral Foundations Theory’, no. UMO-2011/01/N/HS6/02211.

Research presented in this paper was part of Katarzyna Cantarero doctoral thesis. We would like to thank Hillie Aaldering, Wijnand Van Tilburg, Eric Igou, Andero Teras and other friends and colleagues that helped in reaching participants. We thank Katarzyna Byrka for her valuable comments on this work.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Science Centre in Poland (grant number UMO-2011/01/N/HS6/02211).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants engaged in the study.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Stories depicting work-related lying and the instruction used in the study. All the stories that proved to be most representative and allowed to confirm the four factorial structure of lying acceptability are presented in Cantarero et al. (2018, pp. 234–235). Denomination of the type of each lie is in parenthesis (this information was not given to participants).

Presented below are various social situations. Please take a stance on each of them by ticking the extent to which you think the presented behavior can be characterized by a given expression.

On a message from person B (superior of persons A and C) that person C made an error at work, person A tells person B, that person C made the mistake because he/she was not informed about new guidelines, even though person A knows that person C was aware of them. (other-oriented, professional domain)

Person A tells person B (superior of persons A and person C) that person C went to the toilet, even though in fact person C was late to work. (other-oriented, professional domain)

Person A calls to person B (his/her supervisor) and tells him/her that he/she is not feeling well and will not come to work, even though in reality he/she feels good. (egoistic, professional domain)

Person A knows that in order to obtain the possibility of executing a task, which he/she is really counting on, he/she must be skilled in a particular field. He/she says to person B (his/her supervisor) that he/she is skilled in this field even though he/she knows he/she is not as skilled, as he/she claims. (egoistic, professional domain)

Person A informs person B (his/her supervisor) about successes, which in fact he/she did not achieve. (egoistic, professional domain)

Person A tells person B (his/her supervisor), that person C is a co-author of a project, of which person C was supposed to take part in, although in reality person C did not take part in it. (other-oriented, professional domain)

Person A tells person B (supervisor of person A and person C) about the successes of person C, even though he/she knows that he/she did not achieve them. (other-oriented, professional domain)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cantarero, K., Szarota, P., Stamkou, E. et al. The effects of culture and moral foundations on moral judgments: The ethics of authority mediates the relationship between power distance and attitude towards lying to one’s supervisor. Curr Psychol 40, 675–683 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9945-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9945-0