Abstract

Generic early-warning signals such as increased autocorrelation and variance have been demonstrated in time-series of systems with alternative stable states approaching a critical transition. However, lag times for the detection of such leading indicators are typically long. Here, we show that increased spatial correlation may serve as a more powerful early-warning signal in systems consisting of many coupled units. We first show why from the universal phenomenon of critical slowing down, spatial correlation should be expected to increase in the vicinity of bifurcations. Subsequently, we explore the applicability of this idea in spatially explicit ecosystem models that can have alternative attractors. The analysis reveals that as a control parameter slowly pushes the system towards the threshold, spatial correlation between neighboring cells tends to increase well before the transition. We show that such increase in spatial correlation represents a better early-warning signal than indicators derived from time-series provided that there is sufficient spatial heterogeneity and connectivity in the system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abrupt extensive changes have been identified in a range of ecosystems (Scheffer et al. 2001). Some of these shifts are suggested to be critical transitions between alternative states (Scheffer and Carpenter 2003). Such critical transitions have been described, among others, for lakes (Scheffer 1998; Carpenter 2005), for marine and coastal environments (Petraitis and Dudgeon 1999; Daskalov et al. 2007), for terrestrial communities (Handa et al. 2002; Schmitz et al. 2006), and for semi-arid ecosystems (Rietkerk et al. 2004; Narisma et al. 2007).

Predicting critical transitions is a difficult task (Clark et al. 2001). However, recent theoretical work suggests that there may be generic leading indicators for critical transitions even when mechanistic insight is insufficient to build reliable predictive models (Scheffer et al. 2009). The underlying principle of most of these indicators is a phenomenon known in dynamical systems theory as ‘critical slowing down’ (Strogatz 1994). Critical slowing down occurs in most bifurcation points when the dominant eigenvalue characterizing the rates of change around the equilibrium becomes zero. This implies that approaching such critical points, the system becomes slower in recovering from perturbations (Wissel 1984; Held and Kleinen 2004; van Nes and Scheffer 2007). In reality, all systems are permanently subject to disturbances. It has been shown in models that in such situations, one should expect that there is an increase in autocorrelation (Ives 1995; Kleinen et al. 2003; Held and Kleinen 2004) and in variance (Carpenter and Brock 2006) in the pattern of fluctuations as a bifurcation is approached.

A major drawback of such signals is that in practice, real-time detection may come too late to take action, as long time-series of good quality and resolution are needed (Biggs et al. 2009; Scheffer et al. 2009). In theory, spatial patterns may provide more powerful leading indicators, as they contain more information than a single data point in a time-series (Guttal and Jayaprakash 2009; Donangelo et al. 2009). Indeed, various studies have shown spatial signatures of upcoming transitions. For systems that have self-organized pattern formation, there are specific signals (von Hardenberg et al. 2001; Rietkerk et al. 2004; Kéfi et al. 2007). However, these signals tend to be specific to the particular mechanism involved (Pascual and Guichard 2005) and cannot be generalized to other systems. In a stochastic extinction–colonization model, Oborny et al (2005) showed that spatial variance of population densities increases near the critical extinction threshold. In similar stochastic spatial metapopulation models, spatial correlation increases prior to species extinction as a function of occupied patches (Bascompte 2001), transient time to extinction diverges near the spatial threshold (Gandhi et al. 1998; Ovaskainen et al. 2002), and the size of maximum patches declines as habitat fragmentation increases (Bascompte and Sole 1996). Recently, it has been shown that rising variance accompanied by a peak in skewness preludes the transition of an underexploited resource to overexploitation in a spatial model with local alternative stable states (Guttal and Jayaprakash 2009).

Here, we first explore whether critical slowing down might in theory generate spatial signals in spatially heterogeneous ecosystems that can go through a critical transition. In particular, we propose a direct link between critical slowing down and increasing spatial correlation prior to a transition, analogous to what has been demonstrated in non-spatial systems (Scheffer et al. 2009). We show that an increase in spatial correlation can serve as an early-warning signal prior to a bifurcation point. Even though such divergence in long-range coherence has been shown in phase transitions (Stanley 1971; Fisher 1974; Solé et al. 1996), to our knowledge, there is no work that investigates this phenomenon in spatially explicit ecological models of alternative stable states as the ones we use in this study. Furthermore, we compare spatial and temporal correlation as leading indicators of transitions in three different spatially explicit models and we show that their performance depends on the assumptions over the underlying connectivity and heterogeneity of the landscape.

Spatial consequences of critical slowing down

In models, bifurcations represent thresholds where a tiny change in a parameter can lead to a qualitative change in the behavior of the system (Strogatz 1994). At such critical points, the dominant eigenvalue characterizing the rates of change around the equilibrium becomes zero. This implies that approaching such bifurcation points, the system becomes increasingly slow in recovering from small perturbations back to its equilibrium. In the case of the classical fold bifurcation, the consequences can be seen intuitively from stability landscapes (Fig. 1). The size of the basin of attraction around an equilibrium shrinks as the bifurcation point is approached by slowly tuning a control parameter (until the basin of attraction of one of the two equilibria disappears; Fig. 1a, b). However, also the slopes of the stability landscape representing the return rate to equilibrium (engineering resilience) change. As the basin shrinks, these slopes become less steep before they eventually flatten out at the threshold. The corresponding smooth decline in return rates represented by eigenvalues happens in any continuous model approaching a fold bifurcation (Wissel 1984), and analysis of various models shows that such slowing down typically starts already far from the bifurcation point (van Nes and Scheffer 2007; Chisholm and Filotas 2009). If one exposes such a system to stochastic perturbations which are normally distributed and in the limit of the equilibrium so that the linear approximation still holds, slowing down implies that the state of the system at any given moment becomes more and more like its past state, as the return rate to equilibrium goes to zero at the bifurcation (Fig. 1d, f).

Time: balls and cups representation of the stability properties of a system exhibiting alternative stable states. a At high resilience, small disturbances to the equilibrium are counterbalanced by high recovery rates back to equilibrium. As a result, when monitoring the state variable in time, the collected time-series is characterized by low correlation between subsequent values (panels c, d). b At low resilience, the basin of attraction shrinks and the system is closer to the transition point. Small disturbances not only increase the chance of pushing the system to the alternative state, but they are not anymore effectively damped due to low recovery rates back to equilibrium. The resulting time-series is highly autocorrelated (panels e, f). Space: dynamics of two strongly connected units embedded in a hypothetical spatial system. When the system is far away from the transition (high resilience), dynamics in each unit are defined more by their own reaction processes than by dispersion (panel g) and appear weakly correlated (panel h). Close to the transition (low resilience), reaction processes are minimized due to critical slowing down and dispersion dominates (panel i). Units now are strongly correlated (panel j)

What might be the consequence of critical slowing down in a system where we have many coupled units, each with alternative stable states? This may correspond for instance to a spatial grid of an ecosystem model with alternative stable states. If we assume that the conditions are different for each grid cell, i.e., the intrinsic equilibrium states of the units in isolation are different for each grid cell for instance due to different environmental conditions, then the diffusive exchange between the units will continuously tend to reduce such variation between cells. More precisely, the dynamics between two neighboring units (x 1 and x 2) will be governed by a reaction part (f) and a diffusion part governed by a dispersion rate (D):

where p i is a parameter that defines heterogeneity between the two units and c is the control parameter that drives the system to the transition point. The Jacobian matrix of this system at equilibrium \( \left( {x_1^*, x_2^* } \right) \) is:

with eigenvalues:

When connectivity is very low, we may assume that \( D < < f\prime \left( {x_i^*, {p_i},c} \right) \) which renders the eigenvalues of the system equal to: \( {\lambda_1} \approx f\prime \left( {x_1^*, {p_1},c} \right) \) and \( {\lambda_2} \approx f\prime \left( {x_2^*, {p_2},c} \right) \). This assumption basically implies that the two units can be regarded as being disconnected. Under these conditions, each unit is governed by its own dynamics and shifts at a different critical threshold c i . Changes in each unit are independent from each other. As a consequence, one would expect to find no correlation between units.

When there is exchange between the units, units are no longer independent. If connectivity is strong, the critical thresholds at which each unit shifts converge (c 1 ≈ c 2 ≈ c*). When the system is far away from the transition, units are governed by both ‘reaction’ and diffusion processes (Eqs. 3 and 4). Close to the transition point, ‘reaction’ within each unit becomes smaller due to critical slowing down \( \left( {f\prime \left( {x_i^*, {p_i},{c^* }} \right) \to 0} \right) \). On the contrary, diffusion is independent of the proximity to the transition but depends only on the gradient between the two units \( \left( {x_1^* - x_2^* } \right) \). We may thus assume that at this point \( D > > f\prime \left( {x_i^*, {p_i},{c^* }} \right) \), and we may neglect \( f\prime \left( {x_i^*, {p_i},{c^* }} \right) \): the eigenvalues of the system approach: λ 1 ≈ 0 and λ 2 ≈ −2D. This means that the system slows down each unit and diffusion will dominate, equalizing differences between units with rate 2D (the second eigenvalue characterizes the dynamics between the two units). Now, the state in a unit will be strongly dependent on that of its neighbor. As a result, units will become more strongly correlated close to the transition (Fig. 1g–j).

Methods

Models description

We adapt three well-studied minimal models that can have alternative stable states (Table 1). The first model describes a logistically growing resource with fixed grazing rate (Noy-Meir 1975; May 1977). It describes the transition of an underexploited system to overexploitation as grazing pressure crosses a threshold. The second model describes the nutrient dynamics of a eutrophic lake (Carpenter et al. 1999). At low nutrient input rates, the lake remains oligotrophic through nutrient losses to sediment or hypolimnion. At increased nutrient loading, there is a high recycling of nutrients from the sediment or hypolimnion back to the water column due to lower oxygen levels and the lake may suddenly become eutrophic. The third model describes the transition of a clear water shallow lake dominated by macrophytes to a turbid water state where macrophytes are practically absent (Scheffer 1998). It models the interactions between macrophyte coverage and turbidity of a shallow lake.

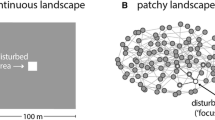

By adding a dispersion term, we can extend the models in two-dimensional space (Okubo 1980). As ecosystems are usually patchy, we assume that space is discrete (Keitt et al 2001), by assuming that the dynamics take place in a n × n-squared lattice which consists of evenly spaced coupled cells (Keitt et al. 2001; van Nes and Scheffer 2005). Each cell can individually switch to its alternative state and is connected with its four neighboring cells. Connectivity is modeled as exchange of matter or biomass among neighboring cells mimicked through a simple diffusive process. Spatial heterogeneity in the landscape (e.g., topographic situation, local hydrological differences) is introduced in the model by randomly and independently setting a parameter p i,j in each cell (Table 1). We also assume there are random independent disturbances in each cell. Thus, the general form of our models is:

where f is the deterministic equation of the non-spatial model that governs the dynamics of the state variable X i,j at each cell as a function of parameter p i,j which introduces heterogeneity among cells, and as a function of c, the control parameter which causes each cell individually to switch between alternative states. D is the dispersion coefficient and dW i,j /dt, a white noise process independently added to each cell with a scaling factor σ (Table 1). To prevent edge effects, we define periodic boundaries for the total lattice.

Models analysis

All simulations started with random initial conditions, where all cells were in the same state. We then increased a control parameter in small steps until a critical value where the shift occurs. After each stepwise change in the control parameter, we ran the model for 1,000 time steps to minimize transient effects. At the end of the 1,000 time steps, we used the last achieved local values of the state variables in each cell of the whole grid (50 × 50 cells) to calculate the spatial correlation of neighboring cells. This index was defined as the two-point correlation for all pairs of cells separated by distance 1, using the Moran’s coefficient (Legendre and Fortin 1989):

in which we associated a weight w i,j to each pair of cells (x i , x j ) which takes the value of 1 for neighboring cells and 0 otherwise. W is the total number of pairs of neighboring cells. To test how parsimonious spatial correlation between neighboring cells for indicating the proximity to a transition is compared to spatial correlation between cells at higher distances, we also estimated spatial correlation at higher lags (δ up to 25). We quantified the increase of spatial correlation at higher distances by estimating the correlation length ψ from the exponential fit exp(−δ/ψ). The correlation length ψ describes the distance over which the behavior of a macroscopic variable is affected by the behavior of another (Solé et al. 1996). A growing correlation length ψ indicates that spatial correlation increases at longer distances.

Since we were interested in comparing changes in the spatial correlation between cells to changes in the temporal autocorrelation within cells (another potential early-warning signal), we also tracked 25 randomly chosen cells (1% of the total lattice) over the last 100 time steps of each run to estimate the temporal autocorrelation at-lag-1 (Held and Kleinen 2004). We thus used an equal amount of information for comparison of the spatial and temporal indicators: 1 × 2,500 cells versus 100 × 25 cells. We calculated temporal autocorrelation using the mean of the autocorrelation at-lag-1 estimated at each of the 25 sampled cells (see simulation scheme in Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 1). To compare the performance of the spatial and temporal indicators, we quantified their trend using the nonparametric Kendall τ rank correlation of the control parameter and the spatial and temporal correlation estimates.

We explored three different levels of heterogeneity (Table 1): (1) no spatial heterogeneity (p i,j equal in all cells), (2) low spatial heterogeneity (p i,j drawn from a uniform distribution with low variance), and (3) high spatial heterogeneity (p i,j drawn from a uniform distribution with high variance). In each of these settings, we studied the effect of different levels of connectivity (mimicked by the diffusive exchange term D = [0, 0.001, 0.0025, 0.005, 0.01, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1]).

Since we are interested in signals that warn before the shift, we excluded the dynamics during the transition from our analysis. In spatial heterogeneous systems, different cells may shift at different times. Therefore, it is not obvious how a threshold point should be determined. Here, we defined a threshold simply as the point when the first cell shifted to the alternative state (see Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 2). This ensures that we are really focusing on early-warning signals rather than detecting changes that occur during the shift itself.

All simulations and statistical analyses were performed in MATLAB (v. 7.0.1). We solved the stochastic equations using a Euler–Murayama integration method with Ito calculus (Grasman J. van Herwaarden OA 1999).

Results

A simplified spatial scenario

To see how critical slowing down affects dynamics in space in a transparent way, we first implemented the overharvesting model of May (1977) in only two cells. In this oversimplified spatial scenario, the two cells have different carrying capacities and are harvested with the same rate. When connectivity is low, each cell shifts at a different harvesting rate. When the system is strongly connected, the two cells shift at the same harvesting pressure (Fig. 2a, b).

Overharvesting model by May (1977) implemented in a simplistic two-cell spatial system. a, b Equilibrium values for resource biomass in both cells as a function of control parameter (harvesting rate c) that shifts the system from high resource biomass to low resource biomass. c, d Perturbation experiment (in both cases 15% reduction in biomass) showing the effect of “critical slowing down” in cell 1 for a highly connected system far and close to the transition. The dotted lines indicate the deterministic equilibrium value of the cell (parameters used: D = 0.5 K 1 = 10, K 2 = 6 r = 1, c = 2 in c, c = 1 in d)

We tested whether critical slowing down occurs despite high connectivity by performing a perturbation experiment (van Nes and Scheffer 2007). Indeed, biomass in the perturbed cell 1 recovered slower before the transition compared to a situation far from the transition (Fig. 2c, d). Note that changes in cell 1 strongly affect dynamics of cell 2 (Fig. 2c). This is in line with our theoretical prediction that close to the transition, units become less responsive to their own dynamics and more influenced by the dynamics of neighboring units. Also, it can be seen that there is a conspicuous increase in similarity as the system approaches the transition provided that there is sufficient connectivity (D; Fig. 3a), and spatial heterogeneity (δ; Fig. 3b).

Effect of connectivity (dispersion rate D) and heterogeneity (δ defined as the difference in the carrying capacities K i of the two cells) on the dissimilarity between neighbors for increasing levels of harvesting rate (c) in the 2 cell spatial overharvesting model by May (1977). a When connectivity is high (D > 0.1) cells not only shift in sync, but they are becoming increasingly similar prior to the transition. b Such increase in similarity is greater the more inherently heterogeneous the cells are (δ > 0)

Correlation in space and time

In the previous analysis, we showed that critical slowing down causes the state of two cells to converge close to a transition. We now explore the effect of critical slowing down in the complete spatial models. Simulations show that indeed, spatial correlation between neighboring cells increased prior to the transition in a wide range of conditions for all three models (see Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 3). For example, in the vegetation–turbidity model spatial correlation between neighboring cells started to increase well before the shift (Fig. 4a, b). As expected, with weakly connected cells (Fig. 4c, d), spatial correlation between neighboring cells did not show a strong increase before the transition.

An example of the evolution of spatial and temporal correlation between neighboring cells in the vegetation turbidity model (Scheffer, 1998). Panels a, c show the spatial mean of the system’s state variable following the slow change in the control parameter. The gray-shaded area indicates the period before the system starts flipping. c Note the shift in the case of low connectivity is gradual, as each cell shifts almost independently from its neighbor. a The shift is abrupt when connectivity is high and the system reaches the transition globally. b Spatial correlation signals well in advance the shift of the lake to turbid conditions, outperforming the increase in temporal autocorrelation. d At low connectivity, spatial correlation hardly changes before the onset of transition, but the trend in temporal autocorrelation is stronger. Top panels are snapshots of the spatial distribution of vegetation cover far from the transition (high resilience), and just before the transition (low resilience; parameter values as in Table 1 for high heterogeneity in h E)

Interestingly, temporal autocorrelation performed in a somehow complementary way compared to spatial correlation (see also Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 4); when connectivity was high, temporal autocorrelation showed a weaker trend with the control parameter (Kendall τ = 0.26, P < 0.05) than its spatial analog (Kendall τ = 0.83, P < 0.05; Fig. 4b). However, trends in temporal autocorrelation (Kendall τ = 0.31, P < 0.05) outperformed trends in spatial correlation when connectivity was low (Kendall τ = 0.1, P > 0.05; Fig. 4d).

To check how generic these results are, we systematically analyzed the trends in the spatial and temporal correlations up to the transition for a range of dispersion and heterogeneity conditions (Fig. 5). The Kendall τ correlation statistic was used to quantify the strength of the trend of the correlation indicators for every level of dispersion rate. A higher value of this trend-statistic implies a more significant increase in the indicator prior to the transition. Despite some differences in the three models, two general patterns emerged: (1) high connectivity between patches favored a strong increase in the spatial correlation of neighbors, especially when there was inherent heterogeneity in the environment; (2) high environmental heterogeneity reduced the strength of the temporal correlation. The latter pattern is due to the fact that in this situation, each cell shifts at a different level of the control parameter, implying that the autocorrelation measured at each cell is different, and consequently the estimate of their mean is noisy. Connectivity had no apparent effect on the trends in temporal autocorrelation.

Summary of the Kendall τ rank correlation coefficients of the temporal and spatial leading indicators estimated for all dispersion levels and heterogeneity conditions for all three models. The Kendall τ statistic measures the strength of the trend of the leading temporal and spatial indicators before the shift of the spatial system. Significance levels for each statistic are summarized in Electronic Supplementary Material Table 1

We checked whether an increase in spatial correlation between neighboring cells for indicating the proximity to a transition is more parsimonious compared to changes in spatial correlation between cells at higher distances. We found that spatial correlation also at higher lags does indeed tend to increase prior to a transition, whereas after the transition, the correlation is limited only to a few neighboring cells (see Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 5a, b). Such increase in long-range coherence is reflected in the growing correlation length ψ which can also serve as leading indicator of an imminent shift (Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 5c) However, the almost 1:1 relationship between the trends of both signals strongly implies that spatial correlation between neighbors is a parsimonious indicator of an upcoming transition (Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 6).

Discussion

Our analysis suggests that an increase in spatial correlation may be a leading indicator for an impending critical transition. Although we explored only three models explicitly, the fact that increased spatial correlation follows from the universal phenomenon of critical slowing down at bifurcations implies that it may be a generic phenomenon for a wide class of transitions (van Nes and Scheffer 2007).

Our results also indicate that given the same number of data-points, spatial correlation may generally outperform indicators derived from time-series as early-warning signal, corroborating to the suggestion that spatial indicators may be more reliable then temporal indicators (Guttal and Jayaprakash 2009). However, we note that the performance of both spatial and temporal indicators depends on the underlying connectivity and heterogeneity of the landscape. For instance, temporal autocorrelation is likely to be better only in homogeneous environments or extremely well-‘mixed’ (connected) systems which effectively start behaving as a single unit (see Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 7). Also, spatial correlation does not work well in systems with very little connectivity (Fig. 4c, d). However, it should be noted that if the environment is heterogeneous in such unconnected systems, temporal information from a single location will not be sufficient to warn for a critical transition on a large scale either, as the monitored patch might shift earlier or later than average. Thus, monitoring many patches is still required in such situations. A practical issue when it comes to optimizing monitoring strategies is that, using remote sensing, it may typically be much easier to obtain information for numerous points in space than for the same amount of points in time (e.g., 1,000 spatially spread sampling points versus 1,000 weekly measurements at the same spot). Still, even if spatial data are easier to obtain, the typical spatial and temporal resolution needed to acquire reliable estimates of the leading indicators remains an open question. This is because such scale will tend to be system-specific. The spatial unit at which information is gathered in order to estimate spatial correlation will be determined by the scale to which processes in the landscape operate. Similarly, temporal dynamics are governed by specific timescales. For instance, had we been monitoring plankton transitions, we should be monitoring the dynamics in days (the generation time for most phytoplankton species).

Clearly, our analysis is merely a starting point when it comes to exploring the possibility of using an increase in spatial correlation as leading indicator for systemic shifts. In most cases, the dispersal of seeds or animals is not only limited to neighboring cells as we assumed in our work. Guttal and Jayaprakash (2009) showed that the performance of spatial variance and spatial skewness as indicators of transitions in the same type of systems is insensitive to different dispersal patterns. We expect that the same will also hold for our results. Another simplified assumption in our models is that we have ignored that landscape characteristics are usually spatially correlated due to the underlying physical morphology or to the ecological memory that shapes the landscape (Peterson 2002). Therefore, for instance, dispersion rates are not expected to be constant across space. Nor growth rates of a particular resource will be uncorrelated in space. Instead connectivity will differ due to fragmentation in the landscape or there will be “islands” of high fertility where growth rates will be higher. We tested these two assumptions and we found that they do not affect the performance of spatial correlation as leading indicator of upcoming transitions (see Electronic Supplementary Material Figs. 8, 9).

One aspect to explore further is the likelihood of false positives (false alarms) or false negatives (no warning). For instance, it could well be that spatial correlation would also rise in situations which are unrelated to the proximity to a critical point (false alarms). As we showed, spatial correlation is dependent on the existing connectivity and environmental heterogeneity. This means for instance that if connectivity increases (e.g., because of stronger currents, increased mixing, etc), spatial correlation also becomes stronger (Fig. 6a). Similarly, false alarms could result from changes in heterogeneity: if heterogeneity in the environment is accentuated as conditions change through time or as small-scale disturbances increase patchiness in the landscape, this could potentially lead to an increase in spatial correlation producing a false warning of an impending shift (Fig. 6b). Just as any early-warning signal, correlation is obviously likely to fail in providing early-warning (false negatives), if systems are hit by large disturbances. A global strong disturbance (compared to a local strong disturbance) may well tip the whole system to the alternative state, leaving no space for warning. To obtain a better feeling for the reliability of leading indicators, it would clearly be important to study their performance in more realistic scenarios of spatially correlated disturbances of multiple scales.

False positives in the performance of spatial correlation between neighbors for indicating the proximity to an upcoming transition in the overharvesting model of May (1977). a Spatial correlation increases as connectivity in the landscape becomes stronger both when the system is far (c = 1) or closer to the transition (c = 1.6; parameter values as in Table 1 for high heterogeneity in r). b Spatial correlation also increases as heterogeneity in the landscape becomes stronger regardless of the proximity to the transition (parameter values as in Table 1 for D = 0.5)

In this study, we explicitly explored only one class of models, e.g., the ones that have a fold bifurcation on a local level. In view of the connection to critical slowing down, we expect spatial correlation to increase also prior to systemic shifts in systems with other bifurcations. For instance, the Hopf bifurcation, marking the transition of a stable to an oscillatory system is associated to critical slowing down (Chisholm and Filotas 2009) and so is the phenomenon of phase locking between coupled oscillators (Leung 2000). On the other hand, sharp transitions are also described in systems with self-organized spatial patterns (von Hardenberg et al. 2001; Rietkerk et al. 2004; Kéfi et al. 2007) for which it is unclear whether they display slowing down. In these systems, Turing instability points give birth to regular pattern formation (HilleRisLambers et al. 2001) or long-range correlations characterized by power law relationships emerge before the transition due to short range interactions (Pascual and Guichard 2005). Clearly, it would be worthwhile exploring the applicability of the correlation indicators presented in this work to a wider class of models.

Finally, we should acknowledge that although early-warning signals for regime shifts are potentially useful for managing transitions of real ecosystems, they still remain elusive in their application. Most of the proposed indicators are developed in simple ecological models and have not yet been tested in the field (Scheffer et al. 2009). Modeling exercises demonstrate that they may well fail to be used successfully in averting impending transitions (Biggs et al. 2009; Contamin and Ellison 2009). One problem is the large amount of data needed (Carpenter et al. 2008; Dakos et al. 2008; Guttal and Jayaprakash 2008). Another drawback is that generic early-warning signals typically do not indicate the proximity to the critical threshold in absolute terms (van Nes and Scheffer 2007). Instead, they can only be used to indicate a relative change of the system’s resilience. Finally, there is the difficulty of moving from science to policy in a swift way (Scheffer et al. 2003; Biggs et al. 2009). Management actions usually take years to implement due to institutional inertia or stakeholders’ conflicting interests. Nonetheless, it is encouraging that there is an increasing number of examples where leading indicators have been identified for real systems (Scheffer et al. 2009), like the marine environment (Beaugrand et al. 2008), semi-arid ecosystems (Kéfi et al. 2007), or even climate (Livina and Lenton 2007; Dakos et al. 2008).

Our results resonate with earlier findings that long-range coherence increases in percolating systems close to phase transitions (Stanley 1971; Solé et al. 1996; Pascual and Guichard 2005), suggesting that changes in spatial correlation may well turn out to be rather generic indicators of shifts in a variety of spatio-temporal systems, like the ones in this study with fold bifurcations. Potential applications might range from anticipating epidemic outbreaks (Davis et al. 2008) and the collapse of metapopulations (Bascompte and Sole 1996) to warning for epileptic seizures (Lehnertz and Elger 1998) or large-scale climate transitions (Tsonis et al. 2007).

References

Bascompte J (2001) Aggregate statistical measures and metapopulation dynamics. J Theor Biol 209:373–379

Bascompte J, Sole RV (1996) Habitat fragmentation and extinction thresholds in spatially explicit models. J Anim Ecol 65:465–473

Beaugrand G, Edwards M, Brander K, Luczak C, Ibanez F (2008) Causes and projections of abrupt climate-driven ecosystem shifts in the North Atlantic. Ecol Lett 11:1157–1168

Biggs R, Carpenter SR, Brock WA (2009) Turning back from the brink: detecting an impending regime shift in time to avert it. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:826–831

Carpenter SR (2005) Eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems: bistability and soil phosphorus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:10002–10005

Carpenter SR, Brock WA (2006) Rising variance: a leading indicator of ecological transition. Ecol Lett 9:311–318

Carpenter SR, Ludwig D, Brock WA (1999) Management of eutrophication for lakes subject to potentially irreversible change. Ecol Appl 9:751–771

Carpenter SR, Brock WA, Cole JJ, Kitchell JF, Pace ML (2008) Leading indicators of trophic cascades. Ecol Lett 11:128–138

Chisholm RA, Filotas E (2009) Critical slowing down as an indicator of transitions in two-species models. J Theor Biol 257:142–149

Clark JS, Carpenter SR, Barber M, Collins S, Dobson A, Foley JA, Lodge DM, Pascual M, Pielke R, Pizer W, Pringle C, Reid WV, Rose KA, Sala O, Schlesinger WH, Wall DH, Wear D (2001) Ecological forecasts: an emerging imperative. Science 293:657–660

Contamin R, Ellison AM (2009) Indicators of regime shifts in ecological systems: what do we need to know and when do we need to know it? Ecol Appl 19:799–816

Dakos V, Scheffer M, van Nes EH, Brovkin V, Petoukhov V, Held H (2008) Slowing down as an early warning signal for abrupt climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:14308–14312

Daskalov GM, Grishin AN, Rodionov S, Mihneva V (2007) Trophic cascades triggered by overfishing reveal possible mechanisms of ecosystem regime shifts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:10518–10523

Davis S, Trapman P, Leirs H, Begon M, Heesterbeek JAP (2008) The abundance threshold for plague as a critical percolation phenomenon. Nature 454:634–637

Donangelo R, Fort H, Dakos V, Scheffer M, van Nes EH (2009) Early Warning Signals for catastrophic shifts in ecosystems: Comparison between spatial and temporal indicators. Int J Bifurcation Chaos in press

Fisher ME (1974) Renormalization group in theory of critical behavior. Rev Mod Phys 46:597–616

Gandhi A, Levin S, Orszag S (1998) "Critical slowing down" in time-to-extinction: an example of critical phenomena in ecology. J Theor Biol 192:363–376

Grasman J. van Herwaarden OA (1999). Asymptotic methods for the Fokker-Planck equation and the exit problem in applications. Springer, New York.

Guttal V, Jayaprakash C (2008) Changing skewness: an early warning signal of regime shifts in ecosystems. Ecol Lett 11:450–460

Guttal V, Jayaprakash C (2009) Spatial variance and spatial skewness: leading indicators of regime shifts in spatial ecological systems. Theor Ecol 2:3–12

Handa IT, Harmsen R, Jefferies RL (2002) Patterns of vegetation change and the recovery potential of degraded areas in a coastal marsh system of the Hudson Bay lowlands. J Ecol 90:86–99

Held H, Kleinen T (2004) Detection of climate system bifurcations by degenerate fingerprinting. Geophys Res Lett 31

HilleRisLambers R, Rietkerk M, Van den Bosch F, Prins HT, De Kroon H (2001) Vegetation pattern formation in semi-arid grazing systems. Ecology 82:50–61

Ives AR (1995) Measuring resilience in stochastic systems. Ecol Monogr 65:217–233

Kéfi S, Rietkerk M, Alados CL, Pueyo Y, Papanastasis VP, ElAich A, de Ruiter PC (2007) Spatial vegetation patterns and imminent desertification in Mediterranean arid ecosystems. Nature 449:213–217

Keitt TH, Lewis MA, Holt RD (2001) Allee effects, invasion pinning, and species’ borders. Am Nat 157:203–216

Kleinen T, Held H, Petschel-Held G (2003) The potential role of spectral properties in detecting thresholds in the Earth system: application to the thermohaline circulation. Ocean Dynam 53:53–63

Legendre P, Fortin MJ (1989) Spatial pattern and ecological analysis. Plant Ecol 80:107–138

Lehnertz K, Elger CE (1998) Can epileptic seizures be predicted? Evidence from nonlinear time series analysis of brain electrical activity. Phys Rev Lett 80:5019–5022

Leung HK (2000) Bifurcation of synchronization as a nonequilibrium phase transition. Physica A 281:311–317

Livina VN, Lenton TM (2007) A modified method for detecting incipient bifurcations in a dynamical system. Geophys Res Lett 34

Noy-Meir I (1975) Stability of grazing systems an application of predator prey graphs. J Ecol 63:459–482

May M (1977) Thresholds and breakpoints in ecosystems with a multiplicity of stable states. Nature 269:471–477

Narisma GT, Foley JA, Licker R, Ramankutty N (2007) Abrupt changes in rainfall during the twentieth century. Geophys Res Lett 34

Oborny B, Meszena G, Szabo G (2005) Dynamics of populations on the verge of extinction. Oikos 109:291–296

Okubo A (1980) Diffusion and ecological problems: mathematical models. Springer, Berlin

Ovaskainen O, Sato K, Bascompte J, Hanski I (2002) Metapopulation models for extinction threshold in spatially correlated landscapes. J Theor Biol 215:95–108

Pascual M, Guichard F (2005) Criticality and disturbance in spatial ecological systems. Trends Ecol Evol 20:88–95

Peterson GD (2002) Contagious disturbance, ecological memory, and the emergence of landscape pattern. Ecosystems 5:329–338

Petraitis PS, Dudgeon SR (1999) Experimental evidence for the origin of alternative communities on rocky intertidal shores. Oikos 84:239–245

Rietkerk M, Dekker SC, de Ruiter PC, van de Koppel J (2004) Self-organized patchiness and catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Science 305:1926–1929

Scheffer M (1998) Ecology of shallow lakes, 1st edn. Chapman and Hall, London

Scheffer M, Carpenter SR (2003) Catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems: linking theory to observation. Trends Ecol Evol 18:648–656

Scheffer M, Carpenter S, Foley JA, Folke C, Walker B (2001) Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature 413:591–596

Scheffer M, Westley F, Brock W (2003) Slow response of societies to new problems: causes and costs. Ecosystems 6:493–502

Scheffer M, Bascompte J, Brock WA, Brovkin V, Carpenter SR, Dakos V, Held H, van Nes EH, Rietkerk M, Sugihara G (2009) Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature 461:53–59

Schmitz OJ, Kalies EL, Booth MG (2006) Alternative dynamic regimes and trophic control of plant succession. Ecosystems 9:659–672

Solé RV, Manrubia SC, Luque B, Delgado J, Bascompte J (1996) Phase transitions and complex systems. Complexity 1:13–26

Stanley E (1971) Introduction to phase transitions and critical phenomena. Clarendon, Oxford

Strogatz SH (1994) Nonlinear dynamics and chaos with applications to physics, biology, chemistry and engineering. Perseus, New York

Tsonis AA, Swanson K, Kravtsov S (2007) A new dynamical mechanism for major climate shifts. Geophys Res Lett 34

van Nes EH, Scheffer M (2005) Implications of spatial heterogeneity for regime shifts in ecosystems. Ecology 86:1797–1807

van Nes EH, Scheffer M (2007) Slow recovery from perturbations as a generic indicator of a nearby catastrophic shift. Am Nat 169:738–747

von Hardenberg J, Meron E, Shachak M, Zarmi Y (2001) Diversity of vegetation patterns and desertification. Phys Rev Lett 8719 Art No 198101

Wissel C (1984) A universal law of the characteristic return time near thresholds. Oecologia 65:101–107

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sasha Panfilov and Notubo Takeuchi for valuable discussions. We also thank Sonia Kéfi, Andrea Downing, Reinette Biggs, and Jordi Bascompte, as well as Alan Hastings and the three anonymous reviewers whose comments helped improve the manuscript. H.F and R.D. are supported by project PDT 63/13 and PEDECIBA-Uruguay. V.D. is supported by a Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research grant (NWO).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Table 1

Kendall correlation statistics for the spatial and temporal correlation trend estimated in the three models analyzed in the main text. Values in bold are two-tail significant (p < 0.05). (DOC 109 kb)

Fig. 1

Schematic description of simulation scheme and sampling protocol for the estimation of the spatial and temporal correlation leading indicators. (DOC 131 kb)

Fig. 2

Bifurcation plots along the control parameter for all models used to define thresholds for assigning cells in one or the other stable state. In the overharvesting model (panel a), cells were considered underexploited if their biomass was higher 5. In the eutrophication model (panel b), patches with nutrient concentration below 1 were considered oligotrophic. In the vegetation turbidity model (panel c), patches with vegetation cover over 50% were considered vegetated. (DOC 88 kb)

Fig. 3

Spatial correlation as a function of control parameter for all levels of connectivity (D) in the three models analyzed in the main text. (DOC 380 kb)

Fig. 4

Mean temporal correlation of the 25 sampled cells as a function of control parameter for all levels of connectivity (D) in the three models analyzed in the main text. (DOC 446 kb)

Fig. 5

Spatial correlation estimated up to 25 cells distance (lags) in the overharvesting model of May (1977). a Each line in the correlogram corresponds to a value of the grazing rate c as the spatial system approaches the transition. The spatial correlation increases not only for the neighboring cells (lag 1) but extends up to approximately 15 cells distance before the shift. b After the transition the correlation is limited only to a few neighboring cells. c A growing correlation length ψ (estimated for each line in panels a, b) indicates increasing correlation at higher distances. (Parameter values as in Table 1 for D = 0.5 and high heterogeneity in r). (DOC 161 kb)

Fig. 6

Kendall τ coefficients of the spatial correlation of neighbors and correlation length indicators estimated for all dispersion levels and heterogeneity conditions for all three models. The Kendall τ coefficient measures the strength of the trend of the spatial correlation and correlation length before the shift of the spatial system. The almost 1:1 relationship between the trends of both indicators strongly implies that spatial correlation between neighbors (lag 1) is a parsimonious indicator of an upcoming transition. (DOC 113 kb)

Fig. 7

Spatial correlation of neighbors and mean temporal correlation of the 25 sampled cells as a function of the control parameter for an extreme high level of connectivity (D = 100) in the overharvesting model with high heterogeneous conditions. As conjectured in the main text, in highly connected systems (due to high dispersal rates) spatial correlation is already high far away from the transition (≈0.897) and rises only slightly before the shift (≈0.946), indicating that its detection can prove problematic. Instead the rise in the temporal autocorrelation is much stronger. (DOC 69 kb)

Fig. 8

The evolution of spatial correlation of neighbors in correlated and uncorrelated landscapes for two levels of connectivity (D) in the overharvesting model of May (1977). Spatial correlation of neighbors is increasing prior to the transition in both correlated and uncorrelated landscapes. Note that the shift is gradual in an uncorrelated landscape but abrupt when there is underlying correlation (panel a). Top panels are images of the spatial distribution of resource biomass growth rates r. Dotted line indicates the transition. (Parameter values as in Table 1 for high heterogeneity in r). (DOC 144 kb)

Fig. 9

The evolution of spatial correlation of neighbors for different patterns of connectivity (D) in the overharvesting model of May (1977). Red line: dispersion is equal to 0.25 across the landscape. Black line: dispersion is randomly assigned between 0.2-0.3 (mean 0.25) across the landscape. Blue line: dispersion is randomly assigned between 0–0.5 (mean 0.25) across the landscape. Spatial correlation of neighbors is increasing prior to the transition in all cases. Dotted line indicates the transition. (Parameter values as in Table 1 for high heterogeneity in growth rates r). (DOC 79 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dakos, V., van Nes, E.H., Donangelo, R. et al. Spatial correlation as leading indicator of catastrophic shifts. Theor Ecol 3, 163–174 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-009-0060-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-009-0060-6