Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) primarily affect the motor and frontotemporal areas of the brain, respectively. These disorders share clinical, genetic, and pathological similarities, and approximately 10–15% of ALS-FTD cases are considered to be multisystemic. ALS-FTD overlaps have been linked to families carrying an expansion in the intron of C9orf72 along with inclusions of TDP-43 in the brain. Other overlapping genes (VCP, FUS, SQSTM1, TBK1, CHCHD10) are also involved in similar functions that include RNA processing, autophagy, proteasome response, protein aggregation, and intracellular trafficking. Recent advances in genome sequencing have identified new genes that are involved in these disorders (TBK1, CCNF, GLT8D1, KIF5A, NEK1, C21orf2, TBP, CTSF, MFSD8, DNAJC7). Additional risk factors and modifiers have been also identified in genome-wide association studies and array-based studies. However, the newly identified genes show higher disease frequencies in combination with known genes that are implicated in pathogenesis, thus indicating probable digenetic/polygenic inheritance models, along with epistatic interactions. Studies suggest that these genes play a pleiotropic effect on ALS-FTD and other diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Ataxia, and Parkinsonism. Besides, there have been numerous improvements in the genotype–phenotype correlations as well as clinical trials on stem cell and gene-based therapies. This review discusses the possible genetic models of ALS and FTD, the latest therapeutics, and signaling pathways involved in ALS-FTD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- fALS:

-

Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- fFTD:

-

Familial frontotemporal dementia

- sALS:

-

Sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- sFTD:

-

Sporadic frontotemporal dementia

- TARDBP :

-

TAR DNA-binding protein-43

- TDP-43 :

-

TAR DNA-binding protein 43

- HIV-1:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- c9orf72:

-

Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72

- FUS :

-

Fused in sarcoma

- SQSTM1 :

-

Sequestrome-1

- SOD1 :

-

Superoxide dismutase 1

- GRN :

-

Granulin

- MAPT :

-

Microtubule-associated protein tau

- VCP :

-

Valosin-containing protein

- PFN1 :

-

Profilin1

- TBK1 :

-

TANK-binding kinase

- CCNF :

-

Cyclin F

- KIF5A :

-

Kinesin family member 5A

- GLT8D1 :

-

Glycosyltransferase 8 domain containing 1

- NEK1 :

-

NIMA-related kinase 1

- CHMP2B:

-

Charged multivesicular body protein 2B

- CHCHD10:

-

Coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain containing 10

- WGS:

-

Whole-genome sequencing

- WES:

-

Whole-exome sequencing

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association studies

- RAN:

-

Repeat-associated non-AUG

- DPR:

-

Dipeptide repeat

- OPTN :

-

Optineurin

- C21orf2 :

-

Chromosome 21 open reading frame 2

- DNAJC7:

-

DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C7

- TBP:

-

TATA-box binding protein

- CTSF:

-

Cathepsin F

- MFSD8:

-

Major facilitator superfamily domain 8

- PGRN:

-

Glycoprotein called progranulin

- TDP-43:

-

TAR DNA-binding protein-43

- hnRNP:

-

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- DPRs:

-

Dipeptide repeat proteins

- TBK1:

-

TANK-binding kinase 1

- UMN:

-

Upper motor neuron

- LMN:

-

Lower motor neuron

- FTLD:

-

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- FTDP-17T:

-

Frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism-17 T

- PSP:

-

Progressive supranuclear palsy

- CBD:

-

Corticobasal degeneration

- NFTs:

-

Neurofibrillary tangles

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- PD:

-

Parkinson’s disease

- CJD:

-

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- UPS:

-

Ubiquitin–proteasome system

- RRM2:

-

Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase subunit M2

- VCP:

-

Valosin-containing protein

- VAPB:

-

VAMP-associated protein B And C

- HNRNPA1:

-

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1

- AMPA:

-

α-Amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate

- GABAA:

-

γ-Aminobutyric acid type A receptors

- LLPS:

-

Liquid–liquid phase separation

- LCD:

-

Low complexity domain

- TUBA4A:

-

Tubulin Alpha 4a

- ALS2:

-

Alsin

- LAMP-2:

-

Lysosomal associated membrane protein-2

- CTSD:

-

Cathepsin D

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- ASOs:

-

Antisense oligonucleotides

- CuATSM:

-

Diacetylbis(N(4)-methylthiosemicarbazonato) copper II

- iPSCs:

-

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

References

Abramzon YA, Fratta P, Traynor BJ, Chia R (2020) The overlapping genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Front Neurosci 14:42

Ji AL, Zhang X, Chen WW, Huang WJ (2017) Genetics insight into the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia spectrum. J Med Genet 54. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104271

Lattante S, Ciura S, Rouleau GA, Kabashi E (2015) Defining the genetic connection linking amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) with frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Trends Genet 31:263–73

Nguyen HP, Van Broeckhoven C, van der Zee J (2018) ALS genes in the genomic era and their implications for FTD. Trends Genet 34

Brenner D, Weishaupt JH (2019) Update on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. CurrOpin Neurol 32

Sirkis DW, Geier EG, Bonham LW, et al (2019) Recent advances in the genetics of frontotemporal dementia. Curr Genet Med Rep 7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40142-019-0160-6

Keogh MJ, Wei W, Aryaman J, et al (2018) Oligogenic genetic variation of neurodegenerative disease genes in 980 postmortem human brains. J NeurolNeurosurg Psychiatry 89. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2017-317234

Bradley WG, Andrew AS, Traynor BJ, et al (2019) Gene-environment-time interactions in neurodegenerative diseases: hypotheses and research approaches. Ann Neurosci 25. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495321

Chou CC, Zhang Y, Umoh ME, et al (2018) TDP-43 pathology disrupts nuclear pore complexes and nucleocytoplasmic transport in ALS/FTD. Nat Neurosci 21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-017-0047-3

Parobkova E, Matej R (2021) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degenerations: similarities in genetic background. Diagnostics 11

Conforti FL, Renton AE, Houlden H (2021) Editorial: multifaceted genes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal dementia. Front Neurosci 15

Chia R, Chiò A, Traynor BJ (2018) Novel genes associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: diagnostic and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol 17

Guerreiro R, Gibbons E, Tábuas-Pereira M, et al (2020) Genetic architecture of common non-Alzheimer’s disease dementias. Neurobiol Dis 142

Ciani M, Benussi L, Bonvicini C, Ghidoni R (2019) Genome wide association study and next generation sequencing: a glimmer of light toward new possible horizons in frontotemporal dementia research. Front Neurosci 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00506

Zhang S, Cooper-Knock J, Weimer AK, et al (2021) Genome-wide identification of the genetic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3744427

Seelaar H, Rohrer JD, Pijnenburg YAL, et al (2011) Clinical, genetic and pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal dementia: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 82

Pottier C, Bieniek KF, Finch NC, et al (2015) Whole-genome sequencing reveals important role for TBK1 and OPTN mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration without motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol 130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1436-x

Marangi G, Traynor BJ (2015) Genetic causes of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: new genetic analysis methodologies entailing new opportunities and challenges. Brain Res 1607

Lagier-Tourenne C, Baughn M, Rigo F, et al (2013) Targeted degradation of sense and antisense C9orf72 RNA foci as therapy for ALS and frontotemporal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1318835110

Martier R, Liefhebber JM, García-Osta A, et al (2019) Targeting RNA-mediated toxicity in C9orf72 ALS and/or FTD by RNAi-based gene therapy. Mol Ther - Nucleic Acids 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2019.02.001

Berry JD, Cudkowicz ME, Windebank AJ, et al (2019) NurOwn, phase 2, randomized, clinical trial in patients with ALS: safety, clinical, and biomarker results. Neurology 93.https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008620

Noori A, Mezlini AM, Hyman BT, et al (2021) Systematic review and meta-analysis of human transcriptomics reveals neuroinflammation, deficient energy metabolism, and proteostasis failure across neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis 149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105225

Renton AE, Chiò A, Traynor BJ (2014) State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat Neurosci 17

DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, et al (2011) Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011

Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, et al (2011) A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010

Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, et al (1993) Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 362.https://doi.org/10.1038/362059a0

Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, et al (1994) Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science (80- ) 264 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8209258

Andersen PM (2006) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with mutations in the CuZn superoxide dismutase gene. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 6

de AraújoBrasil A, de Carvalho MDC, Gerhardt E, et al (2019) Characterization of the activity, aggregation, and toxicity of heterodimers of WT and ALS-associated mutant Sod1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1902483116

Sau D, De Biasi S, Vitellaro-Zuccarello L, et al (2007) Mutation of SOD1 in ALS: a gain of a loss of function. Hum Mol Genet 16. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddm110

Perrone B, Conforti FL (2020) Common mutations of interest in the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: how common are common mutations in ALS genes? Expert Rev Mol Diagn 20

Sibilla C, Bertolotti A (2017) Prion properties of SOD1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and potential therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 9. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a024141

Zelko IN, Mariani TJ, Folz RJ (2002) Superoxide dismutase multigene family: a comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free Radic Biol Med 33

McCord JM, Fridovich I (1969) Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J Biol Chem 244

Dröge W (2002) Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev 82

Rhee SG, Yang KS, Kang SW, et al (2005) Controlled elimination of intracellular H2O2: regulation of peroxiredoxin, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase via post-translational modification. Antioxidants Redox Signal 7

O’Brien EM, Dirmeier R, Engle M, Poyton RO (2004) Mitochondrial protein oxidation in yeast mutants lacking manganese- (MnSOD) or copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD): evidence that mnsod and cuznsod have both unique and overlapping functions in protecting mitochondrial proteins from. J BiolChem 279. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M405958200

Aquilano K, Vigilanza P, Rotilio G, et al (2006) Mitochondrial damage due to SOD1 deficiency in SH‐SY5Y neuroblastoma cells: a rationale for the redundancy of SOD1. FASEB J 20. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.05-5225fje

Klöppel C, Michels C, Zimmer J, et al (2010) In yeast redistribution of Sod1 to the mitochondrial intermembrane space provides protection against respiration derived oxidative stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.129

Fischer LR, Igoudjil A, Magrané J, et al (2011) SOD1 targeted to the mitochondrial intermembrane space prevents motor neuropathy in the Sod1 knockout mouse. Brain 134.https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq314

Vehviläinen P, Koistinaho J, Goldsteins G (2014) Mechanisms of mutant SOD1 induced mitochondrial toxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front Cell Neurosci 8

Valentine JS, Hart PJ (2003) Misfolded CuZnSOD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100

Pansarasa O, Bordoni M, Diamanti L, et al 2018 Sod1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: “ambivalent” behavior connected to the disease Int J Mol Sci 19

Zarei S, Carr K, Reiley L, et al (2015) A comprehensive review of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Surg Neurol Int 6

Brownell AL, Kuruppu D, Kil KE, et al (2015) PET imaging studies show enhanced expression of mGluR5 and inflammatory response during progressive degeneration in ALS mouse model expressing SOD1-G93A gene. J Neuroinflammation 12.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0439-9

Benkler C, O’Neil AL, Slepian S, et al (2018) Aggregated SOD1 causes selective death of cultured human motor neurons. Sci Rep 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34759-z

Grad LI, Rouleau GA, Ravits J, Cashman NR (2017) Clinical spectrum of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 7

Saccon RA, Bunton-Stasyshyn RKA, Fisher EMC, Fratta P (2013) Is SOD1 loss of function involved in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Brain 136

Saba L, Viscomi MT, Caioli S, et al (2016) Altered functionality, morphology, and vesicular glutamate transporter expression of cortical motor neurons from a presymptomatic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cereb Cortex 26. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhu317

van den Bos MAJ, Geevasinga N, Higashihara M, et al (2019) Pathophysiology and diagnosis of ALS: insights from advances in neurophysiological techniques. Int J Mol Sci 20

Özdinler PH, Benn S, Yamamoto TH, et al (2011) Corticospinal motor neurons and related subcerebral projection neurons undergo early and specific neurodegeneration in hSOD1G93A transgenic ALS mice. J Neurosci 31. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4184-10.2011

Wainger BJ, Kiskinis E, Mellin C, et al (2014) Intrinsic membrane hyperexcitability of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient-derived motor neurons. Cell Rep 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.019

Saxena S, Roselli F, Singh K, et al (2013) Neuroprotection through excitability and mTOR required in ALS motoneurons to delay disease and extend survival. Neuron 80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.027

Leroy F, Lamotted’Incamps B, Imhoff-Manuel RD, Zytnicki D (2014) Early intrinsic hyperexcitability does not contribute to motoneuron degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Elife 3. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.04046

Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, et al (2006) Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature 442.https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05016

Gass J, Prudencio M, Stetler C, Petrucelli L (2012) Progranulin: an emerging target for FTLD therapies. Brain Res 1462

Ferrari R, Hernandez DG, Nalls MA, et al (2014) Frontotemporal dementia and its subtypes: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol 13.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70065-1

De Muynck L, Van Damme P (2011) Cellular effects of progranulin in health and disease. In J Mole Neurosci

Holler CJ, Taylor G, Deng Q, Kukar T (2017) Intracellular proteolysis of progranulin generates stable, lysosomal granulins that are haploinsufficient in patients with frontotemporal dementia caused by GRN mutations. eNeuro 4 https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0100-17.2017

Chang MC, Srinivasan K, Friedman BA, et al (2017) Progranulin deficiency causes impairment of autophagy and TDP-43 accumulation. J Exp Med 214.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20160999

Amin S, Carling G, Gan L (2022) New insights and therapeutic opportunities for progranulin-deficient frontotemporal dementia. Curr Opin Neurobiol 72

Valdez C, Wong YC, Schwake M, et al (2017) Progranulin-mediated deficiency of cathepsin D results in FTD and NCL-like phenotypes in neurons derived from FTD patients. Hum Mol Genet 26. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddx364

Ward ME, Taubes A, Chen R, et al (2014) Early retinal neurodegeneration and impaired Ran-mediated nuclear import of TDP-43 in progranulin-deficient FTLD. J Exp Med 211.https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20140214

Azam S, Haque ME, Kim IS, Choi DK (2021) Microglial turnover in ageing-related neurodegeneration: therapeutic avenue to intervene in disease progression. Cells 10

Krabbe G, Minami SS, Etchegaray JI, et al (2017) Microglial NFκB-TNFα hyperactivation induces obsessive-compulsive behavior in mouse models of progranulin-deficient frontotemporal dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1700477114

Weingarten MD, Lockwood AH, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW (1975) A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. ProcNatl Acad Sci U S A 72. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.72.5.1858

Ghetti B, Oblak AL, Boeve BF, et al (2015) Invited review: frontotemporal dementia caused by microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) mutations: a chameleon for neuropathology and neuroimaging. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41 115

Spillantini MG, Bird TD, Ghetti B (1998) Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: a new group of tauopathies. In Brain Pathology

Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, et al (1998) Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol 43. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410430617

Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, et al (1998) Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393.https://doi.org/10.1038/31508

Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, et al (1998) Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737

Lee Virginia MY, Zhukareva V, Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V, et al (1998) Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science (80- ) 282 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.282.5395.1914

Poorkaj P, Grossman M, Steinbart E, et al (2001) Frequency of tau gene mutations in familial and sporadic cases of non-Alzheimer dementia. Arch Neurol 58. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.58.3.383

Pittman AM, Myers AJ, Abou-Sleiman P, et al (2005) Linkage disequilibrium fine mapping and haplotype association analysis of the tau gene in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. J Med Genet 42.https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.2005.031377

Lillo P, Hodges JR (2009) Frontotemporal dementia and motor neurone disease: overlapping clinic-pathological disorders. J Clin Neurosci 16

Lee VMY, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ (2001) Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci 24

Mackenzie IRA, Neumann M (2016) Molecular neuropathology of frontotemporal dementia: insights into disease mechanisms from postmortem studies. J Neurochem

Halliday G, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, et al (2012) Mechanisms of disease in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: gain of function versus loss of function effects. Acta Neuropathol 124

Raffaele F, Claudia M, John H (2019) Genetics and molecular mechanisms of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update and future avenues. Neurobiol Aging 78

Bennion Callister J, Pickering-Brown SM (2014) Pathogenesis/genetics of frontotemporal dementia and how it relates to ALS. Exp Neurol 262

Van Blitterswijk M, Dejesus-Hernandez M, Rademakers R (2012) How do C9ORF72 repeat expansions cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: can we learn from other noncoding repeat expansion disorders? Curr Opin Neurol 25

Hsiung GYR, Dejesus-Hernandez M, Feldman HH, et al (2012) Clinical and pathological features of familial frontotemporal dementia caused by C9ORF72 mutation on chromosome 9p. Brain 135. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr354

Byrne S, Elamin M, Bede P, et al (2012) Cognitive and clinical characteristics of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis carrying a C9orf72 repeat expansion: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Neurol 11.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70014-5

Zhu Q, Jiang J, Gendron TF, et al (2020) Reduced C9ORF72 function exacerbates gain of toxicity from ALS/FTD-causing repeat expansion in C9orf72. Nat Neurosci 23. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0619-5

Ferrari R, Kapogiannis D, D. Huey E, Momeni P (2011) FTD and ALS: a tale of two diseases. Curr Alzheimer Res 8.https://doi.org/10.2174/156720511795563700

Ou SH, Wu F, Harrich D, et al (1995) Cloning and characterization of a novel cellular protein, TDP-43, that binds to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TAR DNA sequence motifs. J Virol 69. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.69.6.3584-3596.1995

Liscic RM, Grinberg LT, Zidar J, et al (2008) ALS and FTLD: two faces of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Eur J Neurol 15

Prasad A, Bharathi V, Sivalingam V, et al (2019) Molecular mechanisms of TDP-43 misfolding and pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Front Mol Neurosci 12

Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Kwong LK et al (2009) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis frontotemporal dementia and beyond:The TDP-43 diseases. J Neurol 256:1205

Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY (2007) TDP-43: a novel neurodegenerative proteinopathy. Curr Opin Neurobiol 17:548–55

Charif SE, Vassallu MF, Salvañal L, Igaz LM (2022) Protein synthesis modulation as a therapeutic approach for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Neural Regen Res 17:1423–1430. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.330593

Schludi MH, May S, Grässer FA, et al (2015) Distribution of dipeptide repeat proteins in cellular models and C9orf72 mutation cases suggests link to transcriptional silencing. Acta Neuropathol 130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1450-z

Cirulli ET, Lasseigne BN, Petrovski S et al (2015) Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science 347:1436–41. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa3650

Freischmidt A, Wieland T, Richter B, et al (2015) Haploinsufficiency of TBK1 causes familial ALS and fronto-temporal dementia. Nat Neurosci 18. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4000

Gijselinck I, Van Mossevelde S, Van Der Zee J, et al (2015) Loss of TBK1 is a frequent cause of frontotemporal dementia in a Belgian cohort. Neurology 85. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002220

Van Rheenen W, Shatunov A, Dekker AM, et al (2016) Genome-wide association analyses identify new risk variants and the genetic architecture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet 48. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3622

Van Mossevelde S, Van Der Zee J, Gijselinck I, et al (2016) Clinical features of TBK1 carriers compared with C9orf72, GRN and non-mutation carriers in a Belgian cohort. Brain 139.https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv358

de Majo M, Topp SD, Smith BN, et al (2018) ALS-associated missense and nonsense TBK1 mutations can both cause loss of kinase function. Neurobiol Aging 71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.06.015

Cui R, Tuo M, Li P, Zhou C (2018) Association between TBK1 mutations and risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia spectrum: a meta-analysis. Neurol Sci 39:811–820

van der Zee J, Gijselinck I, Van Mossevelde S, et al (2017) TBK1 mutation spectrum in an extended european patient cohort with frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mutat 38. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.23161

Dols-Icardo O, García-Redondo A, Rojas-García R, et al (2018) Analysis of known amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia genes reveals a substantial genetic burden in patients manifesting both diseases not carrying the C9orf72 expansion mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 89. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2017-316820

Duan W, Guo M, Yi L et al (2019) Deletion of Tbk1 disrupts autophagy and reproduces behavioral and locomotor symptoms of FTD-ALS in mice. Aging (Albany NY) 11:2457–2476. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.101936

Bonnard M (2000) Deficiency of T2K leads to apoptotic liver degeneration and impaired NF-kappaB-dependent gene transcription. EMBO J 19. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/19.18.4976

Korac J, Schaeffer V, Kovacevic I, et al (2013) Ubiquitin-independent function of optineurin in autophagic clearance of protein aggregates. J Cell Sci 126. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.114926

Heo JM, Ordureau A, Paulo JA, et al (2015) The PINK1-PARKIN mitochondrial ubiquitylation pathway drives a program of OPTN/NDP52 recruitment and TBK1 activation to promote mitophagy. Mol Cell 60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.016

Weidberg H, Elazar Z (2011) TBK1 mediates crosstalk between the innate immune response and autophagy. Sci Signal 4:pe39

Uhlen M, Uhlén M, Fagerberg L et al (2015) Proteomics Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347:1260419

Li X, Zhang Q, Ding Y, et al (2016) Methyltransferase Dnmt3a upregulates HDAC9 to deacetylate the kinase TBK1 for activation of antiviral innate immunity. Nat Immunol 17. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3464

Lattante S, Doronzio PN, Marangi G, et al (2019) Coexistence of variants in TBK1 and in other ALS-related genes elucidates an oligogenic model of pathogenesis in sporadic ALS. Neurobiol Aging 84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.03.010

Müller K, Brenner D, Weydt P, et al (2018) Comprehensive analysis of the mutation spectrum in 301 German ALS families. J NeurolNeurosurg Psychiatry 89. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2017-317611

Pozzi L, Valenza F, Mosca L, et al (2017) TBK1 mutations in Italian patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: genetic and functional characterization. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 88. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2017-316174

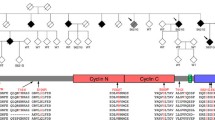

Williams KL, Topp S, Yang S, et al (2016) CCNF mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Nat Commun 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11253

Pan C, Jiao B, Xiao T, et al (2017) Mutations of CCNF gene is rare in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia from Mainland China. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener 18.https://doi.org/10.1080/21678421.2017.1293111

Galper J, Rayner SL, Hogan AL et al (2017) Cyclin F: a component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex with roles in neurodegeneration and cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 89:216–220

Li QS, Tian C, Hinds D, Seabrook GR (2020) The association of clinical phenotypes to known AD/FTD genetic risk loci and their interrelationship. PLoS One 15.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241552

Lee A, Rayner SL, Gwee SSL, et al (2018) Pathogenic mutation in the ALS/FTD gene, CCNF, causes elevated Lys48-linked ubiquitylation and defective autophagy. Cell Mol Life Sci 75.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-017-2632-8

Hogan AL, Don EK, Rayner SL, et al (2017) Expression of ALS/FTD-linked mutant CCNF in zebrafish leads to increased cell death in the spinal cord and an aberrant motor phenotype. Hum Mol Genet 26. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddx136

Yu Y, Nakagawa T, Morohoshi A, et al (2019) Pathogenic mutations in the ALS gene CCNF cause cytoplasmic mislocalization of cyclin F and elevated VCP ATPase activity. Hum Mol Genet 28. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddz119

Brenner D, Yilmaz R, Müller K, et al (2018) Hot-spot KIF5A mutations cause familial ALS. Brain 141.https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx370

Nicolas A, Kenna K, Renton AE, et al (2018) Genome-wide analyses identify KIF5A as a novel ALS gene. Neuron 97.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.02.027

Hirokawa N, Niwa S, Tanaka Y (2010) Molecular motors in neurons: transport mechanisms and roles in brain function development and disease. Neuron 68:610–38

Millecamps S, Julien JP (2013) Axonal transport deficits and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 14:161–76

Kanai Y, Dohmae N, Hirokawa N (2004) Kinesin transports RNA: isolation and characterization of an RNA-transporting granule. Neuron 43.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.022

Guo W, Naujock M, Fumagalli L, et al (2017) HDAC6 inhibition reverses axonal transport defects in motor neurons derived from FUS-ALS patients. Nat Commun 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00911-y

Matsuzaki F, Shirane M, Matsumoto M, Nakayama KI (2011) Protrudin serves as an adaptor molecule that connects KIF5 and its cargoes in vesicular transport during process formation. Mol Biol Cell 22. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E11-01-0068

Xia CH, Roberts EA, Her LS, et al (2003) Abnormalneurofilament transport caused by targeted disruption of neuronal kinesin heavy chain KIF5A. J Cell Biol 161. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200301026

Al-Chalabi A, Andersen PM, Nilsson P, et al (1999) Deletions of the heavy neurofilament subunit tail in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 8. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/8.2.157

Karle KN, Möckel D, Reid E, Schöls L (2012) Axonal transport deficit in a KIF5A -/- mouse model. Neurogenetics 13.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10048-012-0324-y

Smith EF, Shaw PJ, De Vos KJ (2019) The role of mitochondria in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurosci Lett 710:132933

Heisler FF, Lee HK, Gromova K V., et al (2014) GRIP1 interlinks N-cadherin and AMPA receptors at vesicles to promote combined cargo transport into dendrites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1304301111

Nakajima K, Yin X, Takei Y, et al (2012) Molecular motor KIF5A is essential for GABAA receptor transport, and KIF5A deletion causes epilepsy. Neuron 76.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.012

Thiel C, Kessler K, Giessl A, et al (2011) NEK1 mutations cause short-rib polydactyly syndrome type majewski. Am J Hum Genet 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.12.004

Wu CH, Fallini C, Ticozzi N, et al (2012) Mutations in the profilin 1 gene cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 488.https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11280

Campbell PD, Shen K, Sapio MR, et al (2014) Unique function of kinesin Kif5A in localization of mitochondria in axons. J Neurosci 34.https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2770-14.2014

Hares K, Kemp K, Loveless S, et al (2021) KIF5A and the contribution of susceptibility genotypes as a predictive biomarker for multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 268.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10373-w

Cooper-Knock J, Moll T, Ramesh T, et al (2019) Mutations in the glycosyltransferase domain of GLT8D1 are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cell Rep 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.006

Harschnitz O, Jongbloed BA, Franssen H, et al (2014) MMN: from immunological cross-talk to conduction block. J Clin Immunol 34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-014-0026-3

Yu RK, Tsai YT, Ariga T, Yanagisawa M (2011) Structures, biosynthesis, and functions of gangliosides-an overview. J Oleo Sci 60:537–44

Moll T, Shaw PJ, Cooper-Knock J (2020) Disrupted glycosylation of lipids and proteins is a cause of neurodegeneration. Brain 143.https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz358

Sasayama D, Hori H, Yamamoto N, et al (2014) ITIH3 polymorphism may confer susceptibility to psychiatric disorders by altering the expression levels of GLT8D1. J Psychiatr Res 50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.12.002

Yang CP, Li X, Wu Y, et al (2018) Comprehensive integrative analyses identify GLT8D1 and CSNK2B as schizophrenia risk genes. Nat Commun 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03247-3

Mackenzie IR, Nicholson AM, Sarkar M, et al (2017) TIA1 mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia promote phase separation and alter stress granule dynamics. Neuron 95.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.025

Brand P, Dyck PJB, Liu J, et al (2016) Distal myopathy with coexisting heterozygous TIA1 and MYH7 Variants. NeuromusculDisord 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2016.05.012

Hackman P, Sarparanta J, Lehtinen S, et al (2013) Welander distal myopathy is caused by a mutation in the RNA-binding protein TIA1. Ann Neurol 73. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.23831

Klar J, Sobol M, Melberg A, et al (2013) Welander distal myopathy caused by an ancient founder mutation in TIA1 associated with perturbed splicing. Hum Mutat 34. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.22282

van der Spek RA, van Rheenen W, Pulit SL et al (2018) Reconsidering the causality of TIA1 mutations in ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler Front Degener 19:1–3

Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Nicholson A, Pottier C, et al (2018) Clinical and neuropathological features of ALS/FTD with TIA1 mutations . Can J NeurolSci / J Can des Sci Neurol 45. https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2018.48

Hirsch-Reinshagen V, Pottier C, Nicholson AM, et al (2017) Clinical and neuropathological features of ALS/FTD with TIA1 mutations. ActaNeuropathol Commun 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-017-0493-x

Brenner D, Müller K, Wieland T et al (2016) NEK1 mutations in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 139:e28

Kenna KP, Van Doormaal PTC, Dekker AM, et al (2016) NEK1 variants confer susceptibility to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet 48. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3626

Chen Y, Chen CF, Riley DJ, Chen PL (2011) Nek1 kinase functions in DNA damage response and checkpoint control through a pathway independent of ATM and ATR. Cell Cycle 10.https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.10.4.14814

Higelin J, Catanese A, Semelink-Sedlacek LL, et al (2018) NEK1 loss-of-function mutation induces DNA damage accumulation in ALS patient-derived motoneurons. Stem Cell Res 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scr.2018.06.005

Shalom O, Shalva N, Altschuler Y, Motro B (2008) The mammalian Nek1 kinase is involved in primary cilium formation. FEBS Lett 582.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.036

Chang J, Baloh RH, Milbrandt J (2009) The NIMA-family kinase Nek3 regulates microtubule acetylation in neurons. J Cell Sci 122.https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.048975

Smith BN, Ticozzi N, Fallini C, et al (2014) Exome-wide rare variant analysis identifies TUBA4A mutations associated with familial ALS. Neuron 84.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.027

Fang X, Lin H, Wang X, et al (2015) The NEK1 interactor, C21ORF2, is required for efficient DNA damage repair. ActaBiochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 47. https://doi.org/10.1093/abbs/gmv076

Amin P, Florez M, Najafov A, et al (2018) Regulation of a distinct activated RIPK1 intermediate bridging complex I and complex II in TNFα-mediated apoptosis. ProcNatl Acad Sci U S A 115. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1806973115

Khan AO, Eisenberger T, Nagel-Wolfrum K, et al (2015) C21orf2 is mutated in recessive earlyonset retinal dystrophy with macular staphyloma and encodes a protein that localises to the photoreceptor primary cilium. Br J Ophthalmol 99.https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307277

Wang Z, Horemuzova E, Iida A, et al (2017) Axial spondylometaphyseal dysplasia is also caused by NEK1 mutations. J Hum Genet 62.https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2016.157

Wheway G, Schmidts M, Mans DA, et al (2015) An siRNA-based functional genomics screen for the identification of regulators of ciliogenesis and ciliopathy genes. Nat Cell Biol 17. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb3201

Farhan SMK, Howrigan DP, Abbott LE, et al (2019) Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis implicates a novel gene, DNAJC7, encoding a heat-shock protein. Nat Neurosci 22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0530-0

Farhan SMK, Howrigan DP, Abbott LE et al (2019) Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis implicates a novel gene, DNAJC7, encoding a heat-shock protein. Nat Neurosci 22:1966–1974. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-019-0530-0

Olszewska DA, Fallon EM, Pastores GM, et al (2019) Autosomal dominant gene negative frontotemporal dementia-think of SCA17. Cerebellum 18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-018-0998-2

Ranganathan R, Haque S, Coley K et al (2020) Multifaceted genes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-frontotemporal dementia. Front Neurosci 14:684

Van Der Zee J, Mariën P, Crols R, et al (2016) Mutated CTSF in adult-onset neuronal ceroidlipofuscinosis and FTD. Neurol Genet 2. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXG.0000000000000102

Geier EG, Bourdenx M, Storm NJ, et al (2019) Rare variants in the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis gene MFSD8 are candidate risk factors for frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol 137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1925-9

Tang C-H, Lee J-W, Galvez MG, et al (2006) Murine cathepsin F deficiency causes neuronal lipofuscinosis and late-onset neurological disease. Mol Cell Biol 26.https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.26.6.2309-2316.2006

Wang B, Shi GP, Yao PM et al (1999) Human cathepsin F Molecular cloning functional expression, tissue localization, and enzymatic characterization. J Biol Chem 273:3200. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.48.32000

Blauwendraat C, Wilke C, Simón-Sánchez J, et al (2018) The wide genetic landscape of clinical frontotemporal dementia: systematic combined sequencing of 121 consecutive subjects. Genet Med 20. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.102

Siintola E, Topcu M, Aula N, et al (2007) The novel neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis gene MFSD8 encodes a putative lysosomal transporter. Am J Hum Genet 81. https://doi.org/10.1086/518902

Aiello C, Terracciano A, Simonati A, et al (2009) Mutations in MFSD8/CLN7 are a frequent cause of variant-late infantile neuronal ceroidlipofuscinosis. Hum Mutat 30. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.20975

Smith KR, Dahl HHM, Canafoglia L, et al (2013) Cathepsin F mutations cause type B Kufs disease, an adult-onset neuronal ceroidlipofuscinosis. Hum Mol Genet 22. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/dds558

Guerreiro R, Brás J, Hardy J (2015) SnapShot: genetics of ALS and FTD. Cell 160:798

Taskesen E, Mishra A, van der Sluis S, et al (2017) Susceptible genes and disease mechanisms identified in frontotemporal dementia and frontotemporal dementia with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by DNA-methylation and GWAS. Sci Rep 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09320-z

Zhao J, Cooper LT, Boyd AW, Bartlett PF (2018) Decreased signalling of EphA4 improves functional performance and motor neuron survival in the SOD1G93A ALS mouse model. Sci Rep 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29845-1

Karch CM, Wen N, Fan CC, et al (2018) Selective genetic overlap between amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and diseases of the frontotemporal dementia spectrum. JAMA Neurol 75. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0372

Benyamin B, He J, Zhao Q, et al (2017) Cross-ethnic meta-analysis identifies association of the GPX3-TNIP1 locus with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Commun 8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00471-1

Dash BP, Naumann M, Sterneckert J, Hermann A (2020) Genome wide analysis points towards subtype-specific diseases in different genetic forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int J MolSci 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186938

Giannoccaro MP, Bartoletti-Stella A, Piras S, et al (2017) Multiple variants in families with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia related to C9orf72 repeat expansion: further observations on their oligogenic nature. J Neurol 264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-017-8540-x

Cady J, Allred P, Bali T, et al (2015) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis onset is influenced by the burden of rare variants in known amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genes. Ann Neurol 77. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24306

Majounie E, Abramzon Y, Renton AE, et al (2012) Repeat expansion in C9ORF72 in Alzheimer’s disease . N Engl J Med 366. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1113592

Goldman JS, Quinzii C, Dunning-Broadbent J, et al (2014) Multiple system atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a family with hexanucleotide repeat expansions in C9orf72. JAMA Neurol 71.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5762

Cooper DN, Krawczak M, Polychronakos C et al (2013) Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum Genet 132:1077–130

Volk AE, Weishaupt JH, Andersen PM et al (2018) Current knowledge and recent insights into the genetic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Med Genet 30:252–258

Van Blitterswijk M, Van Es MA, Hennekam EAM, et al (2012) Evidence for an oligogenic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 21. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/dds199

Murphy NA, Arthur KC, Tienari PJ, et al (2017) Age-related penetrance of the C9orf72 repeat expansion. Sci Rep 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02364-1

Mis MSC, Brajkovic S, Tafuri F et al (2017) Development of therapeutics for C9ORF72 ALS/FTD-related disorders. Mol Neurobiol 54:4466–4476

Kumar S, Phaneuf D, Cordeau P, et al (2021) Induction of autophagy mitigates TDP-43 pathology and translational repression of neurofilament mRNAs in mouse models of ALS/FTD. MolNeurodegener 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-020-00420-5

Liu Y, Dodart JC, Tran H, et al (2021) Variant-selective stereopure oligonucleotides protect against pathologies associated with C9orf72-repeat expansion in preclinical models. Nat Commun 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21112-8

Van Giau V, An SS, Kim S, Bagyinszky E (2016) TD-P-002: genetic diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorders based on gene panels and primers by next-generation sequencing. Alzheimer’s Dement 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.248

Lacomblez L, Bensimon G, Leigh PN, et al (1996) Dose-ranging study of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91680-3

Abe K, Aoki M, Tsuji S, et al (2017) Safety and efficacy of edaravone in well defined patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 16.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30115-1

Tsai RM, Boxer AL (2014) Treatment of frontotemporal dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol 16:319

Abati E, Bresolin N, Comi G, Corti S (2020) Silence superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1): a promising therapeutic target for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Expert Opin Ther Targets 24:295–310

Li Y, Balasubramanian U, Cohen D, et al (2015) A comprehensive library of familial human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One 10.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118266

Miller TM, Pestronk A, David W, et al (2013) An antisense oligonucleotide against SOD1 delivered intrathecally for patients with SOD1 familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase 1, randomised, first-in-man study. Lancet Neurol 12.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70061-9

Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Cialic R, et al (2015) Targeting miR-155 restores abnormal microglia and attenuates disease in SOD1 mice. Ann Neurol 77. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24304

Vieira FG, Hatzipetros T, Thompson K, et al (2017) CuATSM efficacy is independently replicated in a SOD1 mouse model of ALS while unmetallated ATSM therapy fails to reveal benefits. IBRO Reports 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibror.2017.03.001

Balendra R, Isaacs AM (2018) C9orf72-mediated ALS and FTD: multiple pathways to disease. Nat Rev Neurol 14:544–558

Biferi MG, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Cappelletto A, et al (2017) A new AAV10-U7-mediated gene therapy prolongs survival and restores function in an ALS mouse model. Mol Ther 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.05.017

Scoles DR, Pulst SM (2018) Oligonucleotide therapeutics in neurodegenerative diseases. RNA Biol 15:707–714

Pritchard C, Silk A, Hansen L (2019) Are rises in electro-magnetic field in the human environment, interacting with multiple environmental pollutions, the tripping point for increases in neurological deaths in the Western World? Med Hypotheses 127.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2019.03.018

Bandres-Ciga S, Noyce AJ, Hemani G, et al (2019) Shared polygenic risk and causal inferences in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 85. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25431

Cochran JN, Geier EG, Bonham LW, et al (2020) Non-coding and loss-of-function coding variants in TET2 are associated with multiple neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Hum Genet 106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.03.010

Funding

LK is supported by Malaviya Postdoctoral Fellowship by Institute of Eminence (IoE), Banaras Hindu University (BHU) from Ministry of Education (MoE), Government of India (GOI). Funding from IoE, BHU to MM and AM is duly acknowledged. MM is supported by SERB-Power Fellowship by Science and Engineering Research Board, GOI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. K. and M. M. generated the theme for this article, and L. K. executed the literature search, tabulations, figures, data collection, and analysis. The final draft was edited and modified by L. K., A. M., and M. M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

All authors have given their consent to publish this manuscript in Molecular Neurobiology.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kirola, L., Mukherjee, A. & Mutsuddi, M. Recent Updates on the Genetics of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. Mol Neurobiol 59, 5673–5694 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-022-02934-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-022-02934-z