Abstract

Glycyrrhizin, a component of Chinese medicine licorice root, has the ability to inhibit the functions of high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). While glycyrrhizin is known to have anti-inflammatory activities, the underlying mechanisms by which glycyrrhizin inhibits inflammation during the development of trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced experimental colitis are not well understood. This study systemically examined the regulatory effects of glycyrrhizin on inflammatory response in TNBS-induced murine colitis and explored the potential mechanisms involved in this process. We reported that glycyrrhizin treatment ameliorated colitis and decreased the production of inflammatory mediators HMGB1, IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-17. In addition, glycyrrhizin regulated responses of dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages during the development of colitis. Furthermore, administration of glycyrrhizin suppressed the proliferation of Th17 cells in colitis. Moreover, the ability of DCs and macrophages to induce the differentiation of Th17 cells was enhanced in presence of HMGB1, which was inhibited by glycyrrhizin. These results demonstrated that glycyrrhizin alleviated colitis by inhibiting the promotive effect of HMGB1 on DC/macrophage-mediated Th17 proliferation. In conclusion, HMGB1 plays an important role in the development of colitis. As an inhibitor of HMGB1, glycyrrhizin might be a novel therapy for colitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46–54 e42. quiz e30 doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001.

Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573–621. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225.

Strober W, Fuss I, Mannon P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(3):514–21. doi:10.1172/JCI30587.

Macdonald TT, Monteleone G. Immunity, inflammation, and allergy in the gut. Science. 2005;307(5717):1920–5. doi:10.1126/science.1106442.

Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448(7152):427–34. doi:10.1038/nature06005.

Mowat AM, Agace WW. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(10):667–85.

Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1590–605. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9.

Kato T, Horie N, Hashimoto K, Satoh K, Shimoyama T, Kaneko T, et al. Bimodal effect of glycyrrhizin on macrophage nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 production. In vivo. 2008;22(5):583–6.

Yoshida T, Abe K, Ikeda T, Matsushita T, Wake K, Sato T, et al. Inhibitory effect of glycyrrhizin on lipopolysaccharide and d-galactosamine-induced mouse liver injury. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;576(1–3):136–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.08.012.

Schrofelbauer B, Raffetseder J, Hauner M, Wolkerstorfer A, Ernst W, Szolar OHJ. Glycyrrhizin, the main active compound in liquorice, attenuates pro-inflammatory responses by interfering with membrane-dependent receptor signalling. Biochem J. 2009;421:473–82. doi:10.1042/Bj20082416.

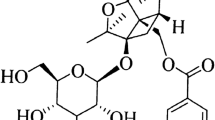

Mollica L, De Marchis F, Spitaleri A, Dallacosta C, Pennacchini D, Zamai M, et al. Glycyrrhizin binds to high-mobility group box 1 protein and inhibits its cytokine activities. Chem Biol. 2007;14(4):431–41. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.007.

Liu Y, Xiang J, Liu M, Wang S, Lee RJ, Ding H. Protective effects of glycyrrhizic acid by rectal treatment on a TNBS-induced rat colitis model. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;63(3):439–46. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01185.x.

Kudo T, Okamura S, Zhang Y, Masuo T, Mori M. Topical application of glycyrrhizin preparation ameliorates experimentally induced colitis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(17):2223–8. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i17.2223.

Hollenbach E, Vieth M, Roessner A, Neumann M, Malfertheiner P, Naumann M. Inhibition of RICK/nuclear factor-kappaB and p38 signaling attenuates the inflammatory response in a murine model of Crohn disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(15):14981–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M500966200.

Elson CO, Beagley KW, Sharmanov AT, Fujihashi K, Kiyono H, Tennyson GS, et al. Hapten-induced model of murine inflammatory bowel disease: mucosa immune responses and protection by tolerance. J Immunol. 1996;157(5):2174–85.

Alex P, Zachos NC, Nguyen T, Gonzales L, Chen TE, Conklin LS, et al. Distinct cytokine patterns identified from multiplex profiles of murine DSS and TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(3):341–52. doi:10.1002/ibd.20753.

Jin Y, Lin Y, Lin L, Zheng C. IL-17/IFN-gamma interactions regulate intestinal inflammation in TNBS-induced acute colitis. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2012;32(11):548–56. doi:10.1089/jir.2012.0030.

Sedhom MAK, Pichery M, Murdoch JR, Foligne B, Ortega N, Normand S, et al. Neutralisation of the interleukin-33/ST2 pathway ameliorates experimental colitis through enhancement of mucosal healing in mice. Gut. 2013;62(12):1714–23. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301785.

Pedrazzi M, Patrone M, Passalacqua M, Ranzato E, Colamassaro D, Sparatore B, et al. Selective proinflammatory activation of astrocytes by high-mobility group box 1 protein signaling. J Immunol. 2007;179(12):8525–32.

Girard JP. A direct inhibitor of HMGB1 cytokine. Chem Biol. 2007;14(4):345–7. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.04.001.

Strober W, Fuss IJ. Proinflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1756–U82. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.016.

Schulz O, Jaensson E, Persson EK, Liu X, Worbs T, Agace WW, et al. Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):3101–14. doi:10.1084/jem.20091925.

Fonseca-Camarillo G, Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Immunoregulatory pathways involved in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(9):2188–93. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000477.

Maddur MS, Miossec P, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. Th17 cells: biology, pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and therapeutic strategies. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(1):8–18. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.03.044.

Huang XL, Zhang X, Fei XY, Chen ZG, Hao YP, Zhang S, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii supernatant ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis by regulating Th17 cell differentiation. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(22):5201–10. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i22.5201.

Messmer D, Yang H, Telusma G, Knoll F, Li J, Messmer B, et al. High mobility group box protein 1: an endogenous signal for dendritic cell maturation and Th1 polarization. J Immunol. 2004;173(1):307–13.

Kokkola R, Andersson A, Mullins G, Ostberg T, Treutiger CJ, Arnold B, et al. RAGE is the major receptor for the proinflammatory activity of HMGB1 in rodent macrophages. Scand J Immunol. 2005;61(1):1–9. doi:10.1111/j.0300-9475.2005.01534.x.

Wenzel UA, Jonstrand C, Hansson GC, Wick MJ. CD103(+)CD11b(+) dendritic cells induce T(h)17 T cells in Muc2-deficient mice with extensively spread colitis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130750. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130750.

Yang L, Dou H, Song YX, Hou YY. Benzenediamine analog FC-99 inhibits TLR2 and TLR4 signaling in peritoneal macrophage in vitro. Life Sci. 2016;144:129–37. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2015.11.023.

Wu Q, Tang Y, Hu X, Wang Q, Lei W, Zhou L, et al. Regulation of Th1/Th2 balance through OX40/OX40L signalling by glycyrrhizic acid in a murine model of asthma. Respirology. 2016;21(1):102–11. doi:10.1111/resp.12655.

Fu YH, Zhou ES, Wei ZK, Liang DJ, Wang W, Wang TC, et al. Glycyrrhizin inhibits the inflammatory response in mouse mammary epithelial cells and a mouse mastitis model. FEBS J. 2014;281(11):2543–57. doi:10.1111/febs.12801.

Yamasaki H, Mitsuyama K, Masuda J, Kuwaki K, Takedatsu H, Sugiyama G, et al. Roles of high-mobility group box 1 in murine experimental colitis. Mol Med Rep. 2009;2(1):23–7. doi:10.3892/mmr_00000056.

Dave SH, Tilstra JS, Matsuoka K, Li F, DeMarco RA, Beer-Stolz D, et al. Ethyl pyruvate decreases HMGB1 release and ameliorates murine colitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86(3):633–43. doi:10.1189/jlb.1008662.

Maeda S, Hikiba Y, Shibata W, Ohmae T, Yanai A, Ogura K, et al. Essential roles of high-mobility group box 1 in the development of murine colitis and colitis-associated cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360(2):394–400. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.065.

Vitali R, Stronati L, Negroni A, Di Nardo G, Pierdomenico M, del Giudice E, et al. Fecal HMGB1 is a novel marker of intestinal mucosal inflammation in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(11):2029–40. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.231.

Vitali R, Palone F, Cucchiara S, Negroni A, Cavone L, Costanzo M, et al. Dipotassium glycyrrhizate inhibits HMGB1-dependent inflammation and ameliorates colitis in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66527. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066527.

Duan LH, Chen J, Zhang HW, Yang H, Zhu P, Xiong A, et al. Interleukin-33 ameliorates experimental colitis through promoting Th2/Foxp3(+) regulatory T-cell responses in mice. Mol Med. 2012;18(5):753–61. doi:10.2119/molmed.2011.00428.

Matteoli G, Mazzini E, Iliev ID, Mileti E, Fallarino F, Puccetti P, et al. Gut CD103(+) dendritic cells express indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase which influences T regulatory/T effector cell balance and oral tolerance induction. Gut. 2010;59(5):595–604. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.185108.

Iliev ID, Spadoni I, Mileti E, Matteoli G, Sonzogni A, Sampietro GM, et al. Human intestinal epithelial cells promote the differentiation of tolerogenic dendritic cells. Gut. 2009;58(11):1481–9. doi:10.1136/gut.2008.175166.

Kim YM, Kim HJ, Chang KC. Glycyrrhizin reduces HMGB1 secretion in lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW 264.7 cells and endotoxemic mice by p38/Nrf2-dependent induction of HO-1. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;26(1):112–8. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2015.03.014.

Dong C. Opinion—diversification of T-helper-cell lineages: finding the family root of IL-17-producing cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(4):329–33. doi:10.1038/nri1807.

Zhang JC, Wu Y, Weng ZL, Zhou T, Feng T, Lin Y. Glycyrrhizin protects brain against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice through HMGB1-TLR4-IL-17A signaling pathway. Brain Res. 2014;1582:176–86. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.07.002.

Iwakura Y, Ishigame H. The IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammation. J Clin Investig. 2006;116(5):1218–22. doi:10.1172/JCI28508.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91542110 to M. Fang), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2013CB530505), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81373167 to M. Fang).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All of the studies were performed in accordance with the Tongji Medical College Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Figure s1

Glycyrrhizin regulated the percentages of IFN-γ+CD4+ T help (Th1) cells and IL-4+CD4+ T help (Th2) cells in the development of colitis. Primary lymphocytes were isolated from the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), colonic lamina propria (cLP) of mice. FACS analysis was performed after staining of anti-CD3, CD4, IFN-γ and IL-4 antibodies. (a) Gating strategies for Th17 cells were illustrated. (b) The percentages of IFN-γ+/CD3+CD4+ T cells in spleen, MLN and cLP were determined. (c) The percentages of IL-4+/CD3+CD4+ T cells in the spleen, MLN and cLP were determined. The cells were gated on CD3+CD4+ T cells. Data represent the mean ± SD, *p≤0.05. The experiments were replicated at least twice. (GIF 42 kb)

Figure s2

Glycyrrhizin regulated the percentages of FoxP3+CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells in the development of colitis. Primary lymphocytes were isolated from the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), colonic lamina propria (cLP) of mice. FACS analysis was performed after staining of anti-CD4 and FoxP3 antibodies. (a) Gating strategies for Treg cells were illustrated. (b) The percentages of FoxP3+CD4+ T cells in the spleen, MLN and cLP were determined. Data represent the mean ± SD, *p≤0.05. The experiments were replicated at least twice. (GIF 23 kb)

Figure s3

Glycyrrhizin inhibited the ability of BMDCs/BMDMs to induce the differentiation of Th1/Th2 cells in the presence or absence of HMGB1. Naive CD4+ T cells were sorted by immunomagnetic selection from spleens. Naive CD4+ T cells (1 × 105) were cultured alone or co-cultured with (a) BMDCs / (b) BMDMs (2.5 × 104) which were treated with or without 100 ng/mL HMGB1 in the presence or absence of glycyrrhizin/anti-HMGB1 antibody for 4 days, and the IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells and IL-4+CD4+ T cells were analyzed by using flow cytometry. Data represent the mean ± SD, *p≤0.05. The experiments were replicated at least twice. (GIF 43 kb)

Figure s10

Flow cytometry scatter plot correspond to figure s2b. (GIF 48 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Fang, D., Li, L. et al. Glycyrrhizin ameliorates experimental colitis through attenuating interleukin-17-producing T cell responses via regulating antigen-presenting cells. Immunol Res 65, 666–680 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-017-8894-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-017-8894-2