Abstract

Purpose of Review

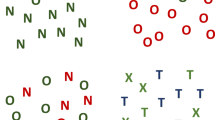

Historical and contemporary treatments of visual agnosia and neglect regard these disorders as largely unrelated. It is thought that damage to different neural processes leads directly to one or the other condition, yet apperceptive variants of agnosia and object-centered variants of neglect share remarkably similar deficits in the quality of conscious experience. Here we argue for a closer association between “apperceptive” variants of visual agnosia and “object-centered” variants of visual neglect. We introduce a theoretical framework for understanding these conditions based on “scale attention”, which refers to selecting boundary and surface information at different levels of the structural hierarchy in the visual array.

Recent Findings

We review work on visual agnosia, the cortical structures and cortico-cortical pathways that underlie visual perception, visuospatial neglect and object-centered neglect, and attention to scale. We highlight direct and indirect pathways involved in these disorders and in attention to scale. The direct pathway involves the posterior vertical segments of the superior longitudinal fasciculus that are positioned to link the established dorsal and ventral attentional centers in the parietal cortex with structures in the inferior occipitotemporal cortex associated with visual apperceptive agnosia. The connections in the right hemisphere appear to be more important for visual conscious experience, whereas those in the left hemisphere appear to be more strongly associated with the planning and execution of visually guided grasps directed at multi-part objects such as tools. In the latter case, semantic and functional information must drive the selection of the appropriate hand posture and grasp points on the object. This view is supported by studies of grasping in patients with agnosia and in patients with neglect that show that the selection of grasp points when picking up a tool involves both scale attention and semantic contributions from inferotemporal cortex. The indirect pathways, which include the inferior fronto-occipital and horizontal components of the superior longitudinal fasciculi, involve the frontal lobe, working memory and the “multiple demands” network, which can shape the content of visual awareness through the maintenance of goal- and task-based abstractions and their influence on scale attention.

Summary

Recent studies of human cortico-cortical pathways necessitate revisions to long-standing theoretical views on visual perception, visually guided action and their integrations. We highlight findings from a broad sample of seemingly disparate areas of research to support the proposal that attention to scale is necessary for typical conscious visual experience and for goal-directed actions that depend on functional and semantic information. Furthermore, we suggest that vertical pathways between the parietal and occipitotemporal cortex, along with indirect pathways that involve the premotor and prefrontal cortex, facilitate the operations of scale attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Martinaud O. Visual agnosia and focal brain injury. Revue Neurologique. 2017;173:451–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2017.07.009.

Perrotta G. Agnosia: Definition, clinical contexts, neurobiological profiles and clinical treatments. Arch Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2020;5:031–5. https://doi.org/10.17352/aggr.000023.

Barton JJS. Disorder of higher visual function. Curr Opin in Neur. 2011;24:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0b013e328341a5c2.

Biran I, Coslett HB. Visual Agnosia. Curr Neur and Neurosci Reports. 2003;3:508–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-003-0055-4.

Coslett H. Visual agnosia, in Marien P. & Abutalebi J. (eds.) Neuropsychological research: a review, pp. 249–266 (New York: Psychology Press, 2008). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203938904.

Farah MJ. Visual agnosia. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004.

Humphreys GW, Riddoch MJ. A reader in visual agnosia. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2016.

Marotta JJ, Behrmann M. “Agnosia,” in encyclopedia of the human brain, VS Ramachandran, Ed., (Academic Press, San Diego, Calif, USA, 2002).

Milner AD, Cavina-Pratesi C. Perceptual deficits of identification: the apperceptive agnosias. Vallar G, Coslett HB (Eds.), Handbook of clinical neurology, Vol. 151: The parietal lobe, 9780444636225, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63622-5.00013-9.

Lissauer H. Ein Fall von Seelenblindheit nebst einem Beiträge zur Theorie derselben. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1890;21:222–70.

Lissauer H, Jackson M. A case of visual agnosia with a contribution to theory. Cogn Neuropsychol. 1988;5:157–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643298808252932.

Marr D. Visual information processing: the structure and creation of visual representations. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1980;290:199–218. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1980.0091.

Efron R. What is perception? Boston Studies in Philosophy of Science. 1968;4:137–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-3378-7_4.

Goodale MA, Milner AD, Jakobson LS, Carey DP. A neurological dissociation between perceiving objects and grasping them. Nature. 1991;349:154–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/349154a0.

Taylor A, Warrington EK. Visual agnosia: a single case report. Cortex. 1972;7:152–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(71)80011-4.

Warrington EK, Taylor AM. The contribution of the right parietal lobe to object recognition. Cortex. 1973;9:152–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(73)80024-3.

Humphreys GW, Riddoch MJ. Routes to object constancy: implications from neurological impairments of object constancy. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1984;36A:385–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/14640748408402169.

Riddoch MJ, Humphreys GW. A case of integrative visual agnosia. Brain. 1987;110:1431–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/110.6.1431.

Riddoch MJ, Humphreys GW, Akhtar N, Allen H, Bracewell MR, Schofield AJ. A tale of two agnosias: distinctions between form and integrative agnosia. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2008;25:56–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643290701848901.

Rizzi C, Piras F, Marangolo P. Top-down projections to the primary visual areas necessary for object recognition: a case study. Vision Res. 2010;50:1074–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2010.03.01.

De Renzi E, Scotti G, Spinnler H. Perceptual and associative disorders of visual recognition: Relationship to the side of the cerebral lesion. Neurology. 1969;19:634–42. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.19.7.634.

Warrington EK, Taylor AM. Two categorical stages of object recognition. Perception. 1978;7:695–705. https://doi.org/10.1068/p070695.

Benson DF, Greenberg JP. Visual form agnosia. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:82–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1969.00480070092010.

Milner AD, Heywood CA. A disorder of lightness discrimination in a case of visual form agnosia. Cortex. 1989;25:489–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(89)80062-0.

Milner AD, Perrett DI, Johnston RS, Benson PJ, Jordan TR, Heeley DW, Bettucci D, Mortara F, Mutani R, Terazzi E, Davidson DLW. Perception and action in ‘visual form agnosia.’ Brain. 1991;114:405–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/114.1.405.

Servos P, Goodale MA, Humphrey GK. The drawing of objects by a visual form agnosic: contribution of surface properties and memorial representations. Neuropsychologia. 1993;31:251–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(93)90089-I.

Bridge H, Thomas OM, Minini L, Cavina-Pratesi C, Milner AD, Parker AJ. Structural and functional changes across the visual cortex of a patient with visual form agnosia. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12779–91. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4853-12.2013.

James TW, Culham J, Humphrey GK, Milner AD, Goodale MA. Ventral occipital lesions impair object recognition but not object-directed grasping: an fMRI study. Brain. 2003;126:2463–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg248.

Steeves JKE, Humphrey GK, Culham JC, Menon RS, Milner AD, Goodale MA. Behavioral and neuroimaging evidence for a contribution of color and texture information to scene classification in a patient with visual form agnosia. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:955–65. https://doi.org/10.1162/0898929041502715.

Eger E, Henson RN, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Mechanisms of top-down facilitation in perception of visual objects studied by fMRI. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2123–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhl119.

Malach R, Reppas JB, Benson RR, Kwong KK, Jiang H, Kennedy WA, Ledden PJ, Brady TJ, Rosen BR, Tootell RB. Object-related activity revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging in human occipital cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:8135–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.18.8135.

Vuilleumier P, Henson R, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Multiple levels of visual object constancy revealed by event-related fMRI of repetition priming. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:491–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn839.

Gauthier I, Tarr MJ. Visual object recognition: Do we (finally) know more now than we did? Annual Review of Vision Science. 2016;2:377–96. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-vision-111815-114621.

Epstein RA, Baker CI. Scene perception in the human brain. Annual Review of Vision Science. 2019;5:373–97. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-vision-091718-014809 (A “state of the field” update on scene perception, with an emphasis on its neural underpinnings across a network of three core ventral stream structures: the parahippocampal place area, the medial place area and the occipital place area, along with discussion of the mid- and high-level functional roles in scene recognition, spatial perception and navigation, and guidance of visual search.)

Cant JS, Goodale MA. Attention to form or surface properties modulates different regions of human occipitotemporal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:713–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhk022.

Cavina-Pratesi C, Kentridge RW, Heywood CA, Milner AD. Separate Processing of Texture and Form in the Ventral Stream: Evidence from fMRI and Visual Agnosia. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:433–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhp111.

Cant JS, Large ME, McCall L, Goodale MA. Independent processing of form, colour, and texture in object perception. Perception. 2008;37:57–78. https://doi.org/10.1068/p5727.

Cant JS, Arnott SR, Goodale MA. fMR-adaptation reveals separate processing regions for the perception of form and texture in the human ventral stream. Exp Brain Res. 2009;192:391–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-008-1573-8.

Cant JS, Goodale MA. Scratching beneath the surface: new insights into the functional properties of the lateral occipital area and parahippocampal place area. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8248–58. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6113-10.2011.

Lowe MX, Rajsic J, Gallivan JP, Ferber S, Cant JS. Neural representation of geometry and surface properties in object and scene perception. Neuroimage. 2017;157:586–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.043.

Riddoch MJ, Humphreys GW, Gannon T, Blott W, Jones V. Memories are made of this: the effects of time on stored visual knowledge in a case of visual agnosia. Brain. 1999;122:537–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/122.3.537.

Lestou V, Lam JML, Humphreys K, Kourtzi Z, Humphreys GW. A dorsal visual route necessary for global form perception: evidence from neuropsychological fMRI. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26:621–34. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00489.

Farah MJ. Visual agnosia. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1990.

Levine DN, Calvanio R. A study of the visual defect in verbal alexia simultanagonosia. Brain. 1978;101:65–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/101.1.65.

Humphreys GW, Riddoch MJ. A case study in visual agnosia revisited: to see but not to see (2nd Edition, Hove). East Sussex: Psychology Press; 2014. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203558096.

Posner MI. Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1980;32:3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335558008248231.

Wolfe JM, Horowitz TS. What attributes guide the deployment of visual attention and how do they do it? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:495–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1411.

Egly R, Driver J, Rafal RD. Shifting visual attention between objects an locations: evidence from normal and parietal lesion subjects. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1994;123:161–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.123.2.161.

de Fockert JW, Rees G, Frith CD, Lavie N. The role of working memory in visual selective attention. Science. 2001;291:1803–6. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1056496.

Chun MM, Golomb JD, Turk-Browne NB. A taxonomy of external and internal attention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:73–101. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100427.

Navon D. Forest before trees: the precedence of global features in visual perception. Cogn Psychol. 1977;9:353–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(77)90012-3.

Robertson LC, Lamb MR. Neuropsychological contributions to theories of part/whole organization. Cogn Psychol. 1991;23:299–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(91)90012-D.

Coren S, Ward LM, Enns JT (2004). Attention. In Sensation and perception, 6th edition (pp. 388–419)

Maunsell JHR, Treue S. Feature-based attention in visual cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:317–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2006.04.001.

Treisman AM, Gelade G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cogn Psychol. 1980;12:97–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5.

Kravitz DJ, Behrmann M. Space-, object-, and feature-based attention interact to organize visual scenes. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2011;73:2434–47. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-011-0201-z.

Vecera SP, Farah MJ. Does visual attention select objects or locations? J Exp Psychol Gen. 1994;123:146–60. https://doi.org/10.1037//0096-3445.123.2.146.

Chica AB, Martín-Arévalo E, Botta F, Lupiáñez J. The Spatial Orienting paradigm: how to design and interpret spatial attention experiments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;40:35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.002.

Posner MI, Walker JA, Friedrich FJ, Rafal RD. Effects of parietal injury on covert orienting of attention. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1863–74. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-07-01863.1984.

de-Wit LH, Kentridge RW, Milner AD. Object-based attention and visual area LO. Neuropsychologia. 2009; 47:1483–1490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.11.002.

Furey ML, Tanskanen T, Beauchamp MS, Avikainen S, Uutela K, Hari R, Haxby JV. Dissociation of face-selective cortical responses by attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1065–70. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0510124103.

O’Craven KM, Downing PE, Kanwisher N. fMRI evidence for objects as the units of attentional selection. Nature. 1999;401:584–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/44134.

Serences JT, Schwarzbach J, Courtney SM, Golay X, Yantis S. Control of object-based attention in human cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1346–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhh095.

Tong F, Nakayama K, Vaughan JT, Kanwisher N. Binocular rivalry and visual awareness in human extrastriate cortex. Neuron. 1998;21:753–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80592-9.

Cohen MA, Dennett DC, Kanwisher N. What is the bandwidth of perceptual experience? Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20:324–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.03.006.

Cohen MA, Alvarez GA, Nakayama K. Natural-scene perception requires attention. Psychol Sci. 2011;22:1165–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611419168.

Jackson-Nielsen M, Cohen MA, Pitts MA. Perception of ensemble statistics requires attention. Conscious Cogn. 2017;48:149–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.11.007.

Brady TF, Shafer-Skelton A, Alvarez GA. Global ensemble texture representations are critical to rapid scene perception. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2017;43:1160–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000399.

Cant JS, Xu Y. Object ensemble processing in human anterior-medial ventral visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7685–700. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3325-11.2012.

Cant JS, Xu Y. The impact of density and ratio on object-ensemble representation in human anterior-medial ventral visual vortex. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:4226–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhu145.

Cant JS, Xu Y. The contribution of object shape and surface properties to object-ensemble representation in anterior-medial ventral visual cortex. The Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2017;29:398–412. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01050.

• Cant JS, Xu Y. One bad apple spoils the whole bushel: the neural basis of outlier processing. NeuroImage. 2020; 211:116629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116629 (An FMRI fast-evented related adaptation design shows that the lateral parahippocampal place area, the lateral occipital cortex and posterior and middle intraparietal cortex are sensitive to the number of outliers in the display, indicating automatic recruitment of these structures in scale-based attention.)

Corbetta M, Patel G, Shulman GL. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron. 2008;58:306–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.017.

Corbetta M, Shulman G. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:201–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn755.

Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Spatial neglect and attention networks. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:569–99. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113731.

Schenkenberg T. Line bisection and unilateral visual neglect in patients with neurologic impairment. Neurology. 1980;30:509–17. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.30.5.509.

Albert ML. A simple test of visual neglect. Neurology. 1973;23:658–64. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.23.6.658.

Gauthier L, Dehaut F, Joanette Y. The bells test – a quantitative and qualitative test for visual neglect. Int J Clin Neuropsychol. 1989;11:49–54.

Heilman KM, Watson RT, Valenstein E. Neglect and related disorders. In Heilman KM, Valenstein E (Eds.), Clinical neuropsychology (p. 296–346). (Oxford University Press, 2003)

Harvey M, Milner AD, Roberts RC. An investigation of hemispatial neglect using the landmark task. Brain Cogn. 1995;27:59–78. https://doi.org/10.1006/brcg.1995.1004.

Chechlacz M, Rotshtein P, Bickerton W-L, Hansen PC, Shoumitro D, Humphreys GW. Separating neural correlates of allocentric and egocentric neglect: distinct cortical sites and common white matter disconnections. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2010;27:277–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643294.2010.519699.

Chechlacz M, Rotshtein P, Humphreys GW. Neuroanatomical dissections of unilateral visual neglect symptoms: ALE meta-analysis of lesion-symptom mapping. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6(230):1–20. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00230.

Karnath H-O, Berger MF, Kuker W, Rorden C. The anatomy of spatial neglect based on voxelwise statistical analysis: a study of 140 patients. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:1164–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhh076.

Karnath H-O, Ferber S, Himmelbach M. Spatial awareness is a function of the temporal not the posterior parietal lobe. Nature. 2001;411:950–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/35082075.

Karnath H-O, Rorden C. The anatomy of spatial neglect. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:1010–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.06.027.

Mort DJ, Malhotra P, Mannan SK, Rorden C, Pambakian A, Kennard C, Husain M. The anatomy of visual neglect. Brain. 2003;126:1986–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg200.

Pedrazzini E, Schnider A, Ptak R. A neuroanatomical model of space-based and object-centered processing in spatial neglect. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222:3605–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-017-1420-4.

Verdon V, Schwartz S, Lovblad K-O, Hauert C-A, Vuilleumier P. Neuroanatomy of hemispatial neglect and its functional components: a study using voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping. Brain. 2010;133:880–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp305.

Wilson B, Cockburn J, Halligan P. Development of a behavioral test of visuospatial neglect. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987;68:98–102.

Mayer E, Martory MD, Pegna AJ, Landis T, Delavelle J, Annoni JM. A pure case of Gerstmann syndrome with a subangular lesion. Brain. 1999;122:1107–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/122.6.1107.

Binder J, Marshall R, Lazar R, Benjamin J, Mohr JP. Distinct syndromes of hemineglect. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:1187–94. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1992.00530350109026.

Danckert J, Ferber S. Revisiting unilateral neglect. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:987–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.09.004.

Husain M, Rorden C. Non-spatially lateralized mechanisms in hemispatial neglect. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:26–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1005.

Driver J, Halligan PW. Can visual neglect operate in object-centred co-ordinates? An affirmative single-case study Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1991;8:475–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643299108253384.

Tipper SP, Behrmann M. Object-centered not scene-based visual neglect. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1996;22:1261–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.22.5.1261.

Azouvi P, Samuel C, Louis-Dreyfus A, Bernati T, Bartolomeo P, Beis J-M, Chokron S, Leclercq M, Marchal F, Martin Y, de Montety G, Olivier S, Perennou D, Pradat-Diehl P, Prairial C, Rode G, Sieroff E, Wiart L, Rousseaux M. Sensitivity of clinical and behavioural tests of spatial neglect after right hemisphere stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:160–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.73.2.160.

Ferber S, Karnath H-O. How to assess spatial neglect-line bisection or cancellation tasks? J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2001;23:599–607. https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.23.5.599.1243.

Sarri M, Greenwood R, Kalra L, Driver J. Task-related modulation of visual neglect in cancellation tasks. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:91–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.08.020.

Ota H, Fujii T, Suzuki K, Fukatsu R, Yamadori A. Dissociation of body centered and stimulus centered representations in unilateral neglect. Neurology. 2001;57:2064–9. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.57.11.2064.

Duncan J, Owen AM. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends in Neuroscience. 2000;23:475–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01633-7.

Fedorenko E, Duncan J, Kanwisher N. Domain-general regions in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:16616–21. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1315235110.

Jung K, Min Y, Han SW. Response of multiple demand network to visual search demands. NeuroImage. 2021;229:117755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117755.

Duncan J. The multiple-demand (MD) system of the primate brain: mental programs for intelligent behaviour. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2010;14:172–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.01.004.

Duncan J. The structure of cognition: attentional episodes in mind and brain. Neuron. 2013;80:35–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.015.

Assem M, Glasser MF, Van Essen DC, Duncan J. A domain-general cognitive core defined in multimodally parcellated human cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2020;30:4361–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhaa023.

Catani M, Jones DK, Donato R, Ffytche DH. Occipito-temporal connections in the human brain. Brain. 2003;126:2093–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg203.

• Latini F, Mårtensson J, Larsson E-M, Fredrikson M, Åhs F, Hjortberg M, et al. Segmentation of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus in the human brain: a white matter dissection and diffusion tensor tractography study. Brain Res. 2017;1675:102–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2017.09.005 (Surgical dissection of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus reveals three major subcomponents: dorsolateral occipital, a dorsomedial occipital and basal that course towards the anterior third of temporal cortex.)

Panesar SS, Yeh F-C, Jacquesson T, Hula W, Fernandez-Miranda JC. A quantitative tractography study into the connectivity, segmentation and laterality of the human inferior longitudinal fasciculus. Front Neuroanat. 2018;12(47):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2018.00047.

Sali G, Briggs RG, Conner AK, Rahimi M, Baker CM, Burks JD, Glenn CA, Battiste JD, Sughrue ME. A connectomic atlas of the human cerebrum—Chapter 11: Tractographic description of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus. Operative Neurosurgery. 2018; 15:S423–S428. https://doi.org/10.1093/ons/opy265.

Conner AK, Briggs RG, Sali G, Rahimi M, Baker CM, Burks JD, Glenn CA, Battiste JD, Sughrue ME. A connectomic atlas of the human cerebrum—Chapter 13: Tractographic description of the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus. Operative Neurosurgery. 2018; 15:S436–S443. https://doi.org/10.1093/ons/opy267.

Lawes IN, Barrick TR, Murugam V, Spierings N, Evans DR, Song M, Clark CA. Atlas-based segmentation of white matter tracts of the human brain using diffusion tensor tractography and comparison with classical dissection. Neuroimage. 2008;39:62–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.06.041.

Martino J, Brogna C, Robles SG, Vergani F, Duffau H. Anatomic dissection of the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus revisited in the lights of brain stimulation data. Cortex. 2010;46:691–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2009.07.015.

Sarubbo S, De Benedictis A, Maldonado IL, Basso G, Duffau H. Frontal terminations for the inferior fronto-occipital fascicle: anatomical dissection, DTI study and functional considerations on a multi-component bundle. Brain Struct Funct. 2013;218:21–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-011-0372-3.

Panichello MF, Cheung OS, Bar M. Predictive feedback and conscious visual experience. Front Psychol. 2013;3(620):1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00620.

Tusa RJ, Ungerleider LG. The inferior longitudinal fasciculus: a reexamination in humans and monkeys. Annual Neurol. 1985;18:583–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410180512.

Mandonnet E, Gatignol P, Duffau H. Evidence for an occipito-temporal tract underlying visual recognition in picture naming. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111:601–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.03.007.

Coello AF, Duvaux S, De Benedictis A, Matsuda R, Duffau H. Involvement of the right inferior longitudinal fascicle in visual hemiagnosia: a brain stimulation mapping study. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:202–5. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.10.JNS12527.

Gil-Robles S, Carvallo A, Jimenez MDM, Caicoya AG, Marinez R, Ruiz-Ocana C, Duffau H. Double dissociation between visual recognition and picture naming: a study of the visual language connectivity using tractography and brain stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:678–86. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0b013e318282a361.

Duffau H, Gatignol P, Mandonnet E, Peruzzi P, Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Capelle L. New insights into the anatomo-functional connectivity of the semantic system: a study using corticosubcortical electrostimulations. Brain. 2005;128:797–810. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh423.

Moritz-Gasser S, Herbet G, Duffau H. Mapping the connectivity underlying multimodal (verbal and non-verbal) semantic processing: a brain electrostimulation study. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51:1814–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.06.007.

Herbert G, Moritz-Gasser S, Duffau H. Direct evidence for the contributive role of the right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus in non-verbal semantic cognition. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222:1597–610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-016-1294-x.

Howard D, Patterson KE. The Pyramids and Palm Trees Test: a test of semantic access from words and pictures. Thames Valley Test Company, Suffolk, 1992.

Parvizi J, Jacques C, Foster BL, Withoft N, Rangarajan V, Weiner KS, Grill-Spector K. Electrical stimulation of human fusiform face-selective regions distorts face perception. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14915–20. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2609-12.2012.

Mégevand P, Groppe DM, Goldfinger MS, Hwang ST, Kingsley PB, Davidesco I, Mehta AD. Seeing scenes: topographic visual hallucinations evoked by direct electrical stimulation of the parahippocampal place area. J Neurosci. 2014;34:5399–405. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5202-13.2014.

Goodale MA, Meenan JP, Bulthoff HH, Nicolle DA, Murphy KJ, Racicot CI. Separate neural pathways for the visual analysis of object shape in perception and prehension. Curr Biol. 1994;4:604–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00132-9.

Karnath H-O, Ruter J, Mandler A, Himmelbach M. The anatomy of object recognition–visual form agnosia caused by medial occipitotemporal stroke. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5854–62. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5192-08.2009.

Carey DP, Harvey M, Milner AD. Visuomotor sensitivity for shape and orientation in a patient with visual form agnosia. Neuropsvchologia. 1996;34:329–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(95)00169-7.

Makris N, Kennedy DN, McInerney S, Sorensen AG, Wang R, Caviness VS, Pandya DN. Segmentation of subcomponents within the superior longitudinal fascicle in humans: a quantitative, in vivo. DT-MRI study Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:854–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhh186.

Komaitis S, Skandalakis GP, Kalyvas AV, Drosos E, Lani E, Emelifeonwu J, Liakos F, Piagkou M, Kalamatianos T, Stranjalis G, Koutsarnakis C. Dorsal component of the superior longitudinal fasciculus revisited: novel insights from a focused fiber dissection study. J Neurosurg. 2020;132:1265–78. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.11.JNS182908.

Parlatini V, Radua J, Dell’Acqua F, Leslie A, Simmons A, Murphy DG, Catani M, de Schotten MT. Functional segregation and integration within fronto-parietal networks. Neuroimage. 2017;146:367–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.031.

Schurr R, Zelman A, Mezer AA. Subdividing the superior longitudinal fasciculus using local quantitative MRI. Neuroimage. 2020;116539:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116439.

Yagmurlu K, Middlebrooks EH, Tanriover N, Rhoton AL. Fiber tracts of the dorsal language stream in the human brain. J Neurosurg. 2016;124:1396–405. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.5.JNS15455.

Binkofski F, Dohle C, Posse S, Stephan KM, Hefter H, Seitz RJ, Freund H-J. Human anterior intraparietal area subserves prehension: a combined lesion and functional MRI activation study. Neurology. 1998;50:1253–9.

Jakobson LS, Archibald YM, Carey DP, Goodale MA. A kinematic analysis of reaching and grasping movements in a patient recovering from optic ataxia. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29:803–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(91)90073-H.

Jeannerod M, Decety J, Michel F. Impairment of grasping movements following a bilateral posterior parietal lesion. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32:369–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(94)90084-1.

Karnath H-O, Perenin MT. Cortical control of visually guided reaching: evidence from patients with optic ataxia. Cereb Cortex. 2005;5:1561–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhi034.

Milner AD, Dijkerman HC, Pisella L, McIntosh RD, Tilikete C, Vighetto A. Rossetti Y. Grasping the past: delay can improve visuomotor performance. Current Biology. 2001; 11:1896–1901. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00591-7.

Perenin MT, Vighetto A. Optic ataxia: a specific disruption in visuomotor mechanisms. I. Different aspects of the deficit in reaching for objects. Brain. 1988; 111:643–674. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/111.3.643.

Cavina-Pratesi C, Goodale MA, Culham JC. FMRI reveals a dissociation between grasping and perceiving the size of real 3D objects. PLOS One. 2007; 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000424.

Culham JC, Danckert JL, DeSouza JF, Gati JS, Menon RS, Goodale MA. Visually guided grasping produces fMRI activation in dorsal but not ventral stream brain areas. Exp Brain Res. 2003;153:180–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-003-1591-5.

Frey SH, Vinton D, Norlund R, Grafton ST. Cortical topography of human anterior intraparietal cortex active during visually guided grasping. Cogn Brain Res. 2005;23:397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.11.010.

Rice NJ, Tunik E, Cross ES, Grafton ST. Online grasp control is mediated by the Contralateral hemisphere. Brain Res. 2007;1175C:76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.009.

Tunik E, Frey ST, Grafton SH. Virtual lesions of the anterior intraparietal area disrupt goal-dependent on-line adjustments of grasp. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:505–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1430.

Davare M, Andres M, Clerget E, Thonnard J-L, Olivier E. Temporal dissociation between hand shaping and grip force scaling in the anterior intraparietal area. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3974–80. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0426-07.2007.

Przybylski L, Kroliczak G. Planning functional grasps of simple tools invokes the hand-independent praxis representation network: an fMRI study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2017;23:108–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617716001120.

Frey SH. Tool use, communicative gesture and cerebral asymmetries in the modern human brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008; 363:1951–1957. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0008.

MacDonald SN, Culham JC. Do human brain areas involved in visuomotor actions show a preference for real tools over visually similar non-tools? Neuropsychologia. 2015;77:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.08.004.

Chen J, Snow JC, Culham JC, Goodale MA. What role does “Elongation” play in “Tool-Specific” activation and connectivity in the dorsal and ventral visual streams? Cereb Cortex. 2017;28:1117–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhx017.

Brandi M-L, Wohlschlager A, Sorg C, Hermsdorfer J. The neural correlates of planning and executing actual tool use. J Neurosci. 2014;34:13183–94. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0597-14.2014.

Hermsdörfer J, Terlinden G, Mühlau M, Goldenberg G, Wohlschläger AM. Neural representations of pantomimed and actual tool use: evidence from an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2007;36:109–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.037.

Styrkowiec PP, Nowik AM, Króliczak G. The neural underpinnings of haptically guided functional grasping of tools: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2019;194:149–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.03.043.

Chieffi S, Gentilucci M, Allport A, Sasso E, Rizzolatti G. Study of selective reaching and grasping in a patient with unilateral parietal lesion: Dissociated effects of residual spatial neglect. Brain. 1993;116:1119–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/116.5.1119.

Pritchard CL, Milner AD, Dijkerman HC, Macwalter RS. Visuospatial neglect: veridical coding of size for grasping but not for perception. Neurocase. 1997;3:437–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13554799708405019.

Harvey M, Milner AD, Roberts RC. An investigation of hemispatial neglect using the landmark task. Brain Cogn. 1995;27:59–78. https://doi.org/10.1006/brcg.1995.1004.

Marotta JJ, McKeeff TJ, Behrmann M. Hemispatial neglect: its effects on visual perception and visually guided grasping. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:1262–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0028-3932(03)00038-1.

Jackson SR. Pathological perceptual completion in hemianopia extends to the control of reach-to-grasp movements. NeuroReport. 1999;10:2461–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-199908200-00005.

Perenin MT, Rossetti Y. Grasping without form discrimination in a hemianopic field. NeuroReport. 1996;7:793–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-199602290-00027.

Whitwell RL, Striemer CL, Nicolle DA, Goodale MA. Grasping the non-conscious: preserved grip scaling to unseen objects for immediate but not delayed grasping following a unilateral lesion to primary visual cortex. Vis Res. 2011;51:908–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2011.02.005.

Buxbaum LJ, Ferraro MK, Veramonti T, Farne A, Whyte J, Ladavas E, Frassinetti F, Coslett HB. Hemispatial neglect: Subtypes, neuroanatomy, and disability. Neurology. 2004;62:749–56. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.WNL.0000113730.73031.F4.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2018-03741) awarded to JTE and an NSERC Postdoctoral Fellowship (487969) awarded to RLW. The authors thank Patrick Brown for his comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Behavior

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whitwell, R.L., Striemer, C.L., Cant, J.S. et al. The Ties that Bind: Agnosia, Neglect and Selective Attention to Visual Scale. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 21, 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-021-01139-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-021-01139-6