Abstract

Purpose of Review

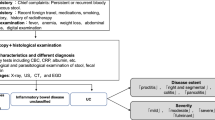

As treatment options for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) continue to expand, the opportunity for hepatotoxicity remains a clinical concern. This review looks to update the current literature on drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and liver-related complications from current and emerging treatments for Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).

Recent Findings

An extensive literature review on currently used medications to treat IBD and their liver-related side effects that includes mesalamine, thiopurines, certain antibiotics, methotrexate, anti-TNF agents including recently introduced biosimilars, anti-integrin therapy, anti-IL 12/IL 23 therapy, and small molecule JAK inhibitors.

Summary

Hepatotoxicity remains an important clinical issue when managing patients with IBD. Clinicians need to remain aware of the potential for liver-related adverse events with various medication classes and adjust their clinical monitoring as appropriate based on the agents being used.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Andrade RJ, Chalasani N, Björnsson ES, Suzuki A, Kullak-Ublick GA, Watkins PB, et al. Drug-induced liver injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):58.

Yaccob A, Mari A. Practical clinical approach to the evaluation of hepatobiliary disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2019;10(3):309–15.

Khokhar OS, Lewis JH. Hepatotoxicity of agents used in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2010;28(3):508–18.

• Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV Jr, Isaacs KL, et al. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(4):481–517 The most recent update on management of Crohns disease by the American College of Gastroenterology highlights how oral mesalamine should not be used for the treatment of active disease.

Ransford RA, Langman MJ. Sulphasalazine and mesalazine: serious adverse reactions re-evaluated on the basis of suspected adverse reaction reports to the Committee on Safety of Medicines. Gut. 2002;51(4):536–9.

Ham M, Moss A. Mesalamine in the treatment and maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Expert Rev Clin Pharamacol. 2013;5(2):113–23.

• Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG Clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384–413 The most recent update on management of ulcerative colitis by the American College of Gastroenterology continues to recommend use of both oral and rectal 5-ASA formulations for mildly active disease.

Sehgal P, Colombel J. Aboubakr et al. systematic review: safety of mesalazine in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(12):1597–609.

Brimblecombe R. Mesalazine: a global safety evaluation. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1990;172:66.

Loftus EV Jr, Kave SV, Bjorkman D. Systematic review: short-term adverse effects of 5-asminosalicylic acid agents in the treatment ofulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(2):179–89.

Love BL, Miller AD. Extended-release mesalamine granules for ulcerative colitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(11):1529–36.

Stoshcus B, Meyhbehm M, Spengler U, et al. Cholestasis associated with mesalazine therapy in a patient with Crohn’s disease. J Hepatol. 1997;26:425–8.

Barroso N, Leo E, Guil A, Larrauri J, Tirado C, Zafra C, et al. Non-immunoallergic hepatotoxicity due to mesalazine. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;22:176–9.

Hautekeete ML, Bourgeois N, Potvin P, et al. Hypersensitivity with hepatotoxicity to mesalazine after hypersensitivity to sulfasalazine. Gastroenterology. 1992;22:176–9.

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Delzicol. 2015. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/204412s006lbl.pdf. 5 Apr 2020.

Feagan BG, Chande N, MacDonald JK. Are there any differences in the efficacy and safety of different formulations of oral 5-ASA used for induction and maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis? Evidence from cochrane reviews. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(9):2031–40.

Bjornsson E, Gu J, Kleiner D, et al. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine induced liver injury: clinical features and outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(1):63–9.

DePinho RA, Goldberg CS, Lefkowitch JH. Azathioprine and the liver: evidence favoring idiosyncratic, mixed cholestatic-hepatocellular injury in man. Gastroenterology. 1984;86(1):162–5.

Romagnuolo J, Sadowski DC, Lalor E, Jewell L, Thomson ABR. Cholestatic hepatocellular injury with azathioprine: a case report and review of the mechanisms of hepatotoxicity. Can J Gastroenterol. 1998;12(7):479–83.

Chaparro M, Ordas I, Cabre E, et al. Safety of thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: long-term follow-up study of 3931 patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(7):1404–10.

Calafat M, Manosa M, Canete F. Increased risk of thiopurine-related adverse events in elderly patients with IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(7):780–8.

Broekman M, Coenen M, Marrewijk C, et al. More dose-dependent side effects with mercaptopurine over azathioprine in IBD treatment due to relatively higher dosing. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(10):1873–81.

Seinen M, Asseldonk D, Boer N, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver in patients with IBD treated with allopurinol-thiopurine combination therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(3):448–52.

Van Asseldonk D, Jharap B, Verheij J, et al. The prevalence of nodular regenerative hyperplasia in inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with thioguanine is not associated with clinically significant liver disease. Inflam Bowel Dis. 2016;22(9):2112–20.

Wanless IR. Micronodular transformation (nodular regenerative hyperplasia) of the liver: a report of 64 cases among 2500 autopsies and a new classification of benign hepatocellular nodules. Hepatology. 1990;11(5):787–97.

Wong D, Coenen M, Derijks L, et al. Early prediction of thiopurine-induced hepatotoxicity in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(3):391–402.

• Marinaki A, Arenas-Hernandez M. Reducing risk in thiopurine therapy. Xenobiotica. 2020;50(1):101–9 Recently published article advocating for continued monitoring of TMPT levels prior to initiation of therapy in addition to monitoring MMP and TGN levels for increased risk of both hepatotoxicity and decreased therapeutic response, respectively.

Dong X, Zheng Q, Zhu M, Tong JL, Ran ZH. Thiopurine S-methyltransferase polymorphisms and thiopurine toxicity in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(25):3187–95.

Schroder T, Scmidt K, Olsen V, et al. Liver steatosis is a risk factor for hepatotoxicity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease under immunosuppressive treatment. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27(6):698–704.

Mottet C, Schoepfer A, Juillerat P, et al. Experts opinion on the practical use of azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(11):2733–47.

Nasser R, Kurnik D, Lurie Y, Nassar L, Yaacob A, Veitsman E, et al. Thiopurine hepatotoxicity can mimic intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020;44(2):e29–31.

Casteele NV, Herfarth H, Katz J, et al. American gastroenterological association institute technical review on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(3):835–57.

•• Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68(suppl 3):s1–s106 A large systematic review which recommends holding thiopurine therapy if LFTs become newly abnormal until resolution of the lab abnormalities.

Vasudevan A, Beswick L, Friedman AB, Moltzen A, Haridy J, Raghunath A, et al. Low-dose thiopurine with allopurinol co-therapy overcomes thiopurine intolerance and allows thiopurine continuation in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(7):682–8.

Meijer B, Seinen M, Egmond R, et al. Optimizing thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease among 2 real-life intercept cohorts: effect of allopurinol comedication. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(11):2011–7.

Kreijne J, deVeer R, DeBoer, et al. Real-life study of safety of thiopurine-allopurinol combination therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: myelotoxicity and hepatotoxicity rarely affect maintenance treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019; 50(4): 407–415.

Chan E, Cronstein B. Methotrexate—how does it really work. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(3):175–8.

Tran-Minh M, Sousa P, Maillet M, et al. Hepatic complications induced by immunosuppressants and biologics in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(13):613–26.

Lewis JH, Schiff E. Methotrexate-induced chronic liver injury: guidelines for detection and prevention. The ACG committee on FDA-related matters. American college of gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83(12):1337–45.

Khan N, Abbas A, Whang N, et al. Incidence of liver toxicity in inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with methotrexate: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(2):359–67.

Saibeni S, Bollani S, Losco A, et al. The use of methotrexate for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;44(2):123–7.

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Methotrexate tablets. 2016. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/008085s066lbl.pdf. 5 Apr 2020.

Conway R, Carey JJ. Risk of liver disease in methotrexate treated patients. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(26):1092–100.

Labadie JG, Jain M. Noninvasive tests to monitor for methotrexate-induced liver injury. Clinical Liver Disease. 2019;13(3):67–71.

Herfarth HH, Kappelman MD, Long MD, Isaacs KL. Use of methotrexate in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(1):224–33.

Ledder O, Turner D. Antibiotics in IBD: still a role in the biological era? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(8):1676–88.

Pardi DS, D’Haens G, Shen B, et al. Clinical guidelines for the management of pouchitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(9):1424–31.

Davis R, Markham A, Balfour JA. Ciprofloxacin. Ciprofloxacin Drugs. 1996;51(6):1019–74.

Radovanovic M, Dushenkovska T, Cvorovic I, Radovanovic N, Ramasamy V, Milosavljevic K, et al. Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury due to ciprofloxacin: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:1152–61.

Grassmick BK, Lehr VT, Sundareson AS. Fulminant hepatic failure possibly related to ciprofloxacin. Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26(5):636–9.

Orman ES, Conjeevaram HS, Freston JW, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of fluoroquinolone-induced liver injury. CGH. 2011;9(6):517–23.

de Silva HJ, Millard PR, Soper N, Kettlewell M, Mortensen N, Jewell DP. Effects of the faecal stream and stasis on the ileal pouch mucosa. Gut. 1991;32:1166–9.

Thia KT, Mahadevan U, Feagan BG, Wong C, Cockeram A, Bitton A, et al. Ciprofloxacin or metronidazole for the treatment of perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(1):17–24.

LiverTox: CMetronidazole. linical and research information on drug-induced liver injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. [Updated 2020 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548609/

Levin AD, Wildenberg ME, van den Brink GR. Mechanism of action of anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2016;10(8):989–97.

Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Vermeire S. Review article: infliximab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease--seven years on. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(4):451–63.

Hoentjen F, van Bodegraven AA. Safety of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(17):2067–73.

•• Shah P, Sundaram V. Bjornsson, Biologic and Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced liver Injury: A Systematic Literature Review. Hepatology Communications. 2020;4(2):172–84 Comprehensive recent systematic review on DILI caused by various biologic agents that are used to treat IBD, organized by MOA. Of note, the FDA issued a drug warning in 2004 due to 130 reported cases of liver injury caused by IFX, which was disproportionate to other TNF-inhibitors.

Menghini VV, Arora AS. Infliximab-associated reversible cholestatic liver disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(1):84–6.

• Koller T, Galambosova M, Filakovska S, et al. Drug-induced liver injury in inflammatory bowel disease: 1-year prospective observational study. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(22):4102–11 Prospective study looking at DILI in BD patients on various therapies. Authors found that hepatocellular injury, although mild and transient, was associated with patients having higher BMI, hepatic steatosis, longer duration of IBD, and receiving treatment with infliximab monotherapy on multivariate analysis.

Parisi I, O’Beirne J, Rossi R, et al. Elevated liver enzymes in inflammatory bowel disease: the role and safety on infliximab. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(7):786–91.

Subramaniam K, Chitturi S, Brown M, Pavli P. Infliximab-induced autoimmune hepatitis in Crohn’s disease treated with budesonide and mycophenolate. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(11):E149–50.

Rodrigues S, Lopes S, Magro F, Cardoso H, Horta e Vale AM, Marques M, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis and anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy: a single center report of 8 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(24):7584–8.

Goldfeld DA, Verna EC, Lefkowitch J, et al. Infliximab-induced autoimmune hepatitis with successful switch to adalimumab in a patient with Crohn’s disease: the index. Case Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(11):3386–8.

Wong F, Ibrahim BA, Walsh J, Qumosani K. Infliximab-induced autoimmune hepatitis requiring liver transplantation. Clinical Case Reports. 2019;7(11):2135–9.

Hahn L, Asmussen D, Benson J. Drug induced-hepatotoxicity with concurrent use of adalimumab and mesalamine for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;2(2):1–4.

• Adar T, Mizrahi M, Pappo O, et al. Adalimumab-induced autoimmune hepatitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010;44(1):e20–2 First case report published to describe case of AIH caused by adalimumab that improved with discontinuation of drug and a course of steroids.

Grasland A, Sterpu R, Boussoukaya S, Mahe I. Autoimmune hepatitis induced by adalimumab with successful switch to abatacept. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(5):895–8.

Kavanaugh A, Husni ME, Harrison DD, Kim L, Lo KH, Leu JH, et al. Safety and efficacy of intravenous golimumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(11):2151–216.

Ling C, Gavin M, Hanson J, McCarthy DM. Progressive epigastric pain with abnormal liver tests in a patient with Crohn’s disease: Don’t DILI dally. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(7):1751–5.

Miehsler W, Novacek G, Wenzl H, Vogelsang H, Knoflach P, Kaser A, et al. A decade of infliximab: the Austrian evidence-based consensus on the safe use of infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(3):221–56.

Perillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on Prevention and Treatment of Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation During Immunosuppressive. Drug Therapy. 2015;148(1):221–44.

•• Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B reactivation associated with immune suppressive and biological modifier therapies: current concepts, management strategies, and future directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1297–309 Updated review article encompassing current diagnosis and treatment modalities of Hepatitis B reactivation due to biologic therapy. TNF-i are considered high risk of potentiating HBV reactivation, particularly in HBsAg-positive patients.

Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, Zhang K, Stadler D, Cheng X, et al. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science. 2014;343(6176):1221–8.

Loomba R, Rowley A, Wesley R, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH, Pucino F, et al. Systematic review: the effect of preventive lamivudine on hepatitis B reactivation during chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(7):519–28.

Rudrapatna VA, Velayos F. Biosimilars for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Pract Gastroenterol. 2019;43(4):84–91.

Nakagawa T, Kobayashi T, Nishikawa K, et al. Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 is interchangeable with its originator for patients with inflammatory bowel disease in real world practice. Intest Res. 2019;17(4):504–15.

“FDA approves Tysabri for Crohn’s disease”. Drugs.com, Jan 2008. https://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/fda-approves-tysabri-moderate-severe-crohn-s-801.html

Keeley KA, Rivey MP, Allington DR. Natalizumab for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39(11): 1833–1843.z

Bezabeh S, Flowers CM, Kortepeter C, Avigan M. Clinically significant liver injury in patients treated with natalizumab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(9):1028–35.

Lisotti A, Azzaroli F, Brillanti S, Mazzella G. Severe acute autoimmune hepatitis after natalizumab treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(4):356–7.

Hillen ME, Cook SD, Samanta A et al. Fatal acute liver failure with hepatitis B virus infection during natalizumab treatment in multiple sclerosis 2015; 2(2): 1–2.

“FDA approves entyvio (vedolizumab) to treat ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease”. Drugs.com 20 May 2014. https://www.drugs.com/newdrugs/fda-approves-entyvio-vedolizumab-ulcerative-colitis-crohn-s-4040.html

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Entyvio (Vedolizumab). 2014. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/125476s000lbl.pdf. 5 Apr 2020.

Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, et al. GEMINI 1 study group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(8):699–710.

Stine JG, Wang J, Behm BW. Chronic cholestatic liver injury attributable to Vedolizumab. Journal of clinical and translational hepatology. 2016;4(3):277–80.

Benson JM, Peritt D, Scallon BJ et al. Discovery and mechanism of ustekinumab: a human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 for treatment of immune-mediated disorders. 2011; 3(6): 535–545.

Papp KA, Langley RG. Lebwohl et al. PHOENIX 2 study investigators. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 2). Lance. 2008;371(9625):1675–84.

Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, Jacobstein D, Lang Y, Friedman JR, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1946–60.

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Stelara (ustekinumab). 2016. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/761044lbl.pdf. 5 Apr 2020.

• Ting SW, Chen YC, Huang YH. Risk of hepatitis B reactivation in patients with psoriasis on ustekinumab. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(9):873–80 Important study showing potential reactivation of hepatitis B in patients on ustekinumab; however, no reported episode of acute liver failure even with reactivation.

Opel D, Economidi A, Chan D, Wasfi Y, Mistry S, Vergou T, et al. Two cases of hepatitis B in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with ustekinumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(12):1498–501.

“Xeljanz Approval History”. Drugs.com. 2012. https://www.drugs.com/history/xeljanz.html

Zhang J, Tsai TF, Lee, et al. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in Asian patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;88(1):36–45.

Valenzuela F, Korman NJ, Bissonnette R, Bakos N, Tsai TF, Harper MK, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: long-term safety and efficacy in an open-label extension study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(4):853–62.

Gupta P, Alvey C, Wang R, Dowty ME, Fahmi OA, Walsky RL, et al. Lack of effect of tofacitinib (CP-690,550) on the pharmacokinetics of the CYP3A4 substrate midazolam in healthy volunteers: confirmation of in vitro data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74(1):109–15.

Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, Curtis JR, Wood SP, Soma K, et al. Safety and efficacy of Tofacitinib, an oral janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in open-label, longterm extension studies. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(5):837–52.

Rigby WF, Lampl K, Low JM, et al. Review of routine laboratory monitoring for patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving biologic or nonbiologic DMARDs. Int J Rheumatol. 2017;2017:9614241.

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Xeljanz (tofacitinib). 2012. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/203214s024,208246s010lbl.pdf. 5 Apr 2020.

Chen YM, Huang WN, Wu YD, Lin CT, Chen YH, Chen DY, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving tofacitinib: a real-world study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(5):780–2.

FDA. Azulfidine (sulfasalazine tablets). 2009. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/007073s124lbl.pdf. 6 Apr 2020.

FDA. Imuran (azathioprine). 2018. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/016324s039lbl.pdf. 6 Apr 2020.

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Purixan (mercaptopurine). 2014. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/205919s000lbl.pdf. 6 Apr 2020.

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Cipro (ciprofloxacin hydrochloride). 2016. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/019537s086lbl.pdf. 6 Apr 2020.

FDA. Flagyl (metronidazole tablets). 2003. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/12623slr059_flagyl_lbl.pdf. 6 Apr 2020.

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Remicade (infliximab). 2013. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/103772s5359lbl.pdf. 6 Apr 2020.

FDA. Highlights of prescribing information: Tysabri (natalizumab). 2012. Web. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/125104s0576lbl.pdf. 6 Apr 2020.

Perillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American gastroenterological association institute technical review on preventions and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterol. 2015;148(1):221–44.

Pattullo V. Prevention of hepatitis B reactivation in the setting of immunosuppression. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22(2):219–37.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept creation and paper Design: JJJ, JHL

Data acquisition, literature review: JJJ, MSB, JMS

Drafting and revision: JJJ, MSB, JMS, JHL

Final draft approval: JJJ, MSB, JMS, JHL

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dr. Barnhill and Dr. Steinberg are joint first authors for this paper.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Liver

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barnhill, M.S., Steinberg, J.M., Jennings, J.J. et al. Hepatotoxicty of Agents Used in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a 2020 Update. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 22, 47 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-020-00781-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-020-00781-3