Abstract

Objective

To investigate cardiac manifestations and the risk factors in Han Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods

Seven hundred fifty SLE patients who were hospitalized at our department were recruited in the present study. The patients were divided into two groups—those with or without cardiac manifestations. Cardiac manifestations in those SLE patients, such as pericarditis, myocarditis, heart valve disease, arrhythmia, were analyzed. The risk and protective factors of cardiac diseases in patients with SLE, as well as the predictors of mortality, were assessed, respectively.

Results

In all 750 SLE patients, there were 339 (45.20%) patients suffered from one or more cardiac manifestations, involving pericarditis in 9.5%, myocarditis in 5.7%, heart valve disease in 15.6%, arrhythmia in 16.67%, and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in 14%. 15.7% of SLE patients were accompanied with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), of which 13.7% were mild, 1.2% were moderate, and 0.8% were severe. No significant differences were found between the two groups in age, disease duration, gender, antibody, and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI). The incidence of pericarditis, heart valve disease, arrhythmia, and PAH was positively correlated with age. The incidence of arrhythmia, CVD, and PAH was correlated with SLEDAI. PAH and myocarditis were the risk factors of mortality in SLE patients with disease duration ≤ 10 years (P = 0.034 and 0.001, respectively).

Conclusion

Cardiac involvement is common in Han Chinese SLE patients and associated with age and disease activity. PAH and myocarditis are the risk factors of mortality in SLE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SLE is an autoimmune disease characterized by multiorgan manifestations, such as skin rash, arthralgias, ulcer, baldness, and autoimmune disorders. It has been well-known that cardiac involvement is often as the poor prognosis in SLE [1, 2]. It also relates to disease severity and adverse drug reactions [3].The cardiac manifestations can arise from endocardium, myocardium, pericardium, valves, conduction system, and vessels [4, 5].

Cardiovascular diseases are frequent in SLE patients. There were regional and racial differences in cardiac manifestations and related risk factors in patients with SLE [6]. The pathological and clinical characteristics of SLE have not been completely elucidated until now. Many studies about cardiac manifestations in SLE patients were focused on only few cases rather than population. Thus, cardiac manifestations and their risk predictors in Han Chinese SLE patients were explored in our study.

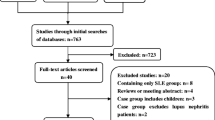

Study population

Seven hundred fifty SLE patients were recruited from the department of rheumatology of the Fourth Clinical Medical College and the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine consecutively between May 2005 and May 2017. The race of all the patients was Han. The diagnosis of SLE was defined according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Classification Criteria [7]. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Commission of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine.

Clinical data of all subjects, including gender, age, disease duration, autoantibodies (anti-ACA antibody, anti-SSA antibody, anti-SSB antibody, anti-dsDNA antibody, anti-Sm antibody and ANA), were collected. Transthoracic Doppler-echocardiography and troponin were used to diagnose pericardial effusion, PAH, CAD, myocarditis, and heart valve disease. The electrocardiogram was used to assess arrhythmia, CAD, and myocarditis. According to pulmonary artery systolic pressure, PAH was classified as mild (35–59 mmHg), moderate (59–89 mmHg), and severe (> 89 mmHg) [8].

The mean age of all patients was (36.59 ± 14.52) years old, and 88.8% of the patients (n = 666) was female. The mean disease duration was (4.72 ± 5.94) years. The positive rate of anti-ACA, anti-SSA, anti-SSB, anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm antibodies, and ANA was 5.3%, 51.7%, 15.6%, 52.5%, 30.5%, and 80.4%, respectively. Disease activity was evaluated by the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) [9]. The patients were divided into two groups—those with or without cardiac manifestations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 162, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For continuous variables, data were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (\( \overline{x} \) ± s). Chi-square test and the independent samples t test were used to evaluate the statistical difference between the two groups. The risk and protective factors of cardiac manifestations in SLE were examined by binary logistic regression analysis. Data with 10% significance were used to build the multivariate linear regression model, in which a stepwise methodology was applied to yield the best model. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Cardiac manifestations in SLE patients

Table 1 shows cardiac manifestations in SLE patients. In all 750 SLE patients, there were 339 (45.20%) patients suffered from one or more cardiac manifestations, involving pericarditis in 9.5% (n = 71), myocarditis in 5.7% (n = 43), heart valve disease in 15.6% (n = 117), arrhythmia in 16.67% (n = 125), and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in 14% (n = 105). 15.7% of SLE patients were accompanied with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), of which 13.7% were mild, 1.2% were moderate, and 0.8% were severe.

Parameter differences between with and without cardiac manifestations group

Then, the parameters were compared between with and without cardiac manifestations group (Table 2). No significant differences were found in age, disease duration, gender, autoantibodies, and SLEDAI between the two groups.

The risk and protective factors of cardiac manifestations in SLE patients

Furthermore, we analyzed the risk and protective factors of cardiac manifestations in SLE (Table 3). The risk factors included age, disease duration, gender, antibody (ACA, SSA, SSB, ds-DNA, Sm, ANA), and SLEDAI (P < 0.05). Age was the predictive factor of pericarditis and arrhythmia (P = 0.011, 0.027; OR 0.975, 0.984; 95% CI, 0.956–0.994, 0.969–0.998, respectively); however, it was the risk factor of the heart valve disease (P = 0.023; OR1.023; 95% CI, 1.009–1.038). Different degrees of SLEDAI were the risk factors (moderate, P = 0.001; OR 2.356; 95% CI, 1.407–3.945 and severe, P = 0.016; OR 2.021; 95% CI, 1.137–3.591). However, mild degree of SLEDAI was the protective factor of myocarditis (P = 0.005; OR 0.326; 95% CI, 0.150–0.709), moderate degree of SLEDAI was the risk factor of arrhythmias (P = 0.029; OR 1.774; 95% CI, 1.062–2.063). Age was the risk factor of PAH (P = 0.013), while SLEDA (remission) was the protective factor of PAH (P = 0.030).

The predictors of mortality in SLE patients with disease duration ≤ 10 years

In order to explore the relationship between cardiac involvement and SLE-related death, we analyzed the predictors of mortality in 654 SLE patients with disease duration ≤ 10 years (Table 4). PAH and myocarditis were the risk factors of mortality in SLE patients with disease duration ≤ 10 years (P = 0.034 and 0.001, respectively; OR 6.275; 95% CI 2.033–19.372); but pericarditis, arrhythmia, heart valve disease, and CVD were not the risk factors of mortality in SLE patients with disease duration ≤ 10 years.

Discussion

Cardiac involvement is a common and severe symptom in SLE patients. It has been reported that the cumulative incidence rate of cardiovascular disease in SLE increased widely [4]. Cardiac manifestations in Chinese SLE patients have unique characteristics.

A retrospective study on PAH in 93 SLE patients found that pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) elevated in 13% of SLE patients (including White, Black, North Africa, and Other races) by noninvasive assessment [10]. And among the cases, morbidity, anti-Sm, and anti-cardiolipin antibodies were statistically different. The PAH-related morbidity in SLE patients was similar to the result of our study (15.7%); however, there were no differences in autoantibodies between the two studies.

The mechanism of arrhythmias in SLE patients has not been completely understood. The reports about the specific antibodies in arrhythmias, such as anti-Ro/SSA and anti-RNP, were controversial [11,12,13]. In our study, SLEDAI was the predictor of arrhythmias. SLEDAI may be correlated with pericarditis, myocarditis, atherosclerotic myocarditis, and small vessel vasculitis with collagen and fibrotic deposits, which leads to abnormality of conduction system [14, 15].

Previous studies have shown the prevalence of heart valve disease in SLE has ranged from 12 to 73% [16,17,18,19,20,21]. Vivero et al. found that valve lesions could be seen in 25% of Caucasian SLE patients, and age was the predictor of valvular thickening and dysfunction [22], while the prevalence of this report was higher than that of our study (15.6%). Similarly, age was also as the predictor in Vivero et al.’s report [22]. Valvulitis and cicatrisation could promote the development of thickening and deformation of vessels, resulting in valvular dysfunction in elderly SLE patients [23].

Pericarditis is one of the most common cardiac manifestations in SLE. Approximately 25% of SLE patients developed symptomatic pericarditis [24, 25]. Autopsy studies revealed even a higher incidence rate of subclinical pericarditis in SLE [25].The morbidity of SLE patients in other races was higher than Chinese SLE patients. Inflammatory exudate with neutrophil predominance and autoantibodies were found in pericardial effusion of SLE patients. Histopathology of pericarditis often found immune complex deposition, monocytes, and fibrinous substance [26, 27]. In our study, age was confirmed to be the predictor of pericarditis in SLE patients.

A recent study have shown morbidity of CVD was the highest among the blacks (10.57%) and lowest among the Asians (6.63%) [28]. The percentage of morbidity in Asian SLE patients was 3%, with a tenfold risk compared to the general population and a 50-fold risk at reproductive age [29, 30]. But CVD-related morbidity of in Chinese SLE patients was lower in our study. The risk factors included oxidized low-density lipoprotein, autoantibodies against endothelial cells and phospholipids, type I interferons (IFN-I), and extracellular neutrophils [31]. SLEDAI was the predictor of CVD in our study, which may be affected by immunological regulation.

The autopsy studies showed that subclinical myocarditis may commonly occur in 57% of SLE patients. It can be the initial cardiac manifestation during the progression of SLE in, particularly, among the untreated patients [32]. A French study showed that myocarditis was the first symptom in 58.6% of SLE patients [33], while 5.7% of Chinese SLE patients suffered from myocarditis in our study. Steroids and cyclophosphamide provide therapy for lupus myocarditis [34, 35]. Some reports showed that plasmapheresis [36] or high dose of intravenous immunoglobulin treatment [37] could improve myocarditis in SLE patients.

The wide use of glucocorticoid and immunosuppressive agents has improved symptoms and survival of SLE patients. However, glucocorticoids can increase the risk of lupus cardiovascular disease and cardiac death. Until now, the status of cardiovascular diseases in Han Chinese SLE patients has not been clarified. In this study, we selected SLE patients with disease duration ≤ 10 years and found that the risk factors for cardiac death of Han Chinese SLE patients were PAH and myocarditis. PAH significantly decreased survival time and quality of life in patients with connective tissue diseases [38]. A meta-analysis of six studies including 323 SLE patients accompanying PAH, which were carried out in the UK, the USA, China, and Japan, demonstrated that 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rate was 88%, 81%, and 68%, respectively [39]. Apte et al. analyzed myocarditis in multiethnic cohorts of the USA and found that 53 of 496 SLE patients had myocarditis, and myocarditis was associated with short life span, particularly in patients with disease duration ≥ 5 years [40].

Our study had some limitations. It was a retrospective study and needed to be further verified. The assessment methods of heart diseases were not strictly unified, so only indirect detection was used to evaluate cardiac diseases in SLE patients. The effects of treatment on heart diseases in SLE were not assessed, which need to explore in the further study.

In conclusion, we confirmed cardiac manifestations are common in Han Chinese SLE patients. Age and disease activity increase the risk of cardiac manifestations. PAH and myocarditis are the risk predictors of mortality in SLE patients.

References

Ballocca F, D’Ascenzo F, Moretti C et al (2015) Predictors of cardiovascular events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 22:1435–1441. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487314546826

Yurkovich M, Vostretsova K, Chen W, Aviña-Zubieta JA (2014) Overall and cause-specific mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 66:608–616. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22173

Pirro M, Stingeni L, Vaudo G, Mannarino MR, Ministrini S, Vonella M, Hansel K, Bagaglia F, Alaeddin A, Lisi P, Mannarino E (2015) Systemic inflammation and imbalance between endothelial injury and repair in patients with psoriasis are associated with preclinical atherosclerosis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 22:1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487314538858

Doria A, Iaccarino L, Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Turriel M, Petri M (2005) Cardiac involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 14:683–686. https://doi.org/10.1191/0961203305lu2200oa

Tincani A, Biasini-Rebaioli C, Cattaneo R, Riboldi P (2005) Nonorgan specific autoantibodies and heart damage. Lupus 14:656–659. https://doi.org/10.1191/0961203305lu2194oa

Garcia MA, Alarcon GS, Boggio G, Hachuel L, Marcos AI, Marcos JC, Gentiletti S, Caeiro F, Sato EI, Borba EF, Brenol JCT, Massardo L, Molina-Restrepo JF, Vasquez G, Guibert-Toledano M, Barile-Fabris L, Amigo MC, Huerta-Yanez GF, Cucho-Venegas JM, Chacon-Diaz R, Pons-Estel BA, on behalf of the Grupo Latino Americano de Estudio del Lupus Eritematoso (GLADEL) (2014) Primary cardiac disease in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: protective and risk factors--data from a multi-ethnic Latin American cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 53:1431–1438. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keu011

Hochberg MC (1997) Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40:1725. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(199709)40:9<1725::AID-ART29>3.0.CO;2-Y

Galie N, Torbicki A, Barst R et al (2004) Guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The Task Force on Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 25:2243–2278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2004.09.014

Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH, Austin A, Bell A, Bloch DA, Corey PN, Decker JL, Esdaile J, Fries JF, Ginzler EM, Goldsmith CH, Hochberg MC, Jones JV, Riche NGHL, Liang MH, Lockshin MD, Muenz LR, Sackett DL, Schur PH (1992) Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The committee on prognosis studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum 35:630–640

Fois E, Le Guern V, Dupuy A et al (2010) Noninvasive assessment of systolic pulmonary artery pressure in systemic lupus erythematosus: retrospective analysis of 93 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 28:836–841

Lazzerini PE, Capecchi PL, Guideri F, Bellisai F, Selvi E, Acampa M, Costa A, Maggio R, Garcia-Gonzalez E, Bisogno S, Morozzi G, Galeazzi M, Laghi-Pasini F (2007) Comparison of frequency of complex ventricular arrhythmias in patients with positive versus negative anti-Ro/SSA and connective tissue disease. Am J Cardiol 100:1029–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.04.048

Lazzerini PE, Acampa M, Guideri F, Capecchi PL, Campanella V, Morozzi G, Galeazzi M, Marcolongo R, Laghi-Pasini F (2004) Prolongation of the corrected QT interval in adult patients with anti-Ro/SSA-positive connective tissue diseases. Arthritis Rheum 50:1248–1252. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.20130

Zuppa AA, Riccardi R, Frezza S, Gallini F, Luciano RMP, Alighieri G, Romagnoli C, de Carolis S (2017) Neonatal lupus: follow-up in infants with anti-SSA/Ro antibodies and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 16:427–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2017.02.010

Fonseca E, Crespo M, Sobrino JA (1994) Complete heart block in an adult with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 3:129–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/096120339400300213

Comin-Colet J, Sanchez-Corral MA et al (2001) Complete heart block in an adult with systemic lupus erythematosus and recent onset of hydroxychloroquine therapy. Lupus 10:59–62. https://doi.org/10.1191/096120301673172543

Falcao CA, Alves IC, Chahade WH et al (2002) Echocardiographic abnormalities and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arq Bras Cardiol 79:285–291

Gentile R, Lagana B, Tubani L et al (2000) Assessment of echocardiographic abnormalities in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: correlation with levels of antiphospholipid antibodies. Ital Heart J 1:487–492

Morelli S, Bernardo ML, Viganego F, Sgreccia A, de Marzio P, Conti F, Priori R, Valesini G (2003) Left-sided heart valve abnormalities and risk of ischemic cerebrovascular accidents in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 12:805–812. https://doi.org/10.1191/0961203303lu468oa

Perez-Villa F, Font J, Azqueta M, Espinosa G, Pare C, Cervera R, Reverter JC, Ingelmo M, Sanz G (2005) Severe valvular regurgitation and antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective, long-term, follow-up study. Arthritis Rheum 53:460–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21162

Ferreira E, Bettencourt PM, Moura LM (2012) Valvular lesions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome: an old disease but a persistent challenge. Rev Port Cardiol 31:295–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2012.02.005

Roldan CA, Shively BK, Lau CC, Gurule FT, Smith EA, Crawford MH (1992) Systemic lupus erythematosus valve disease by transesophageal echocardiography and the role of antiphospholipid antibodies. J Am Coll Cardiol 20:1127–1134

Vivero F, Gonzalez-Echavarri C, Ruiz-Estevez B, Maderuelo I, Ruiz-Irastorza G (2016) Prevalence and predictors of valvular heart disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev 15:1134–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2016.09.007

Roldan CA, Shively BK, Crawford MH (1996) An echocardiographic study of valvular heart disease associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 335:1424–1430. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199611073351903

Moder KG, Miller TD, Tazelaar HD (1999) Cardiac involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mayo Clin Proc 74:275–284. https://doi.org/10.4065/74.3.275

Galve E, Candell-Riera J, Pigrau C, Permanyer-Miralda G, Garcia-del-Castillo H, Soler-Soler J (1988) Prevalence, morphologic types, and evolution of cardiac valvular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 319:817–823. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198809293191302

Lindop R, Arentz G, Thurgood LA, Reed JH, Jackson MW, Gordon TP (2012) Pathogenicity and proteomic signatures of autoantibodies to Ro and La. Immunol Cell Biol 90:304–309. https://doi.org/10.1038/icb.2011.108

Quismorio FP Jr (1980) Immune complexes in the pericardial fluid in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Intern Med 140:112–114

Barbhaiya M, Feldman CH, Guan H, Gómez-Puerta JA, Fischer MA, Solomon DH, Everett B, Costenbader KH (2017) Race/ethnicity and cardiovascular events among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 69:1823–1831. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40174

Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Grodzicky T, Li Y, Panaritis C, Berger RD, Côte R, Grover SA, Fortin PR, Clarke AE, Senécal JL (2001) Traditional Framingham risk factors fail to fully account for accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 44:2331–2337

Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, Conte CG, Medsger TA, Jansen-McWilliams L, D’Agostino RB, Kuller LH (1997) Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 145:408–415

Giannelou M, Mavragani CP (2017) Cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus: a comprehensive update. J Autoimmun 82:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2017.05.008

Zawadowski GM, Klarich KW, Moder KG, Edwards WD, Cooper LT Jr (2012) A contemporary case series of lupus myocarditis. Lupus 21:1378–1384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203312456752

Thomas G, Cohen Aubart F, Chiche L, Haroche J, Hié M, Hervier B, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Mazodier K, Ebbo M, Cluzel P, Cordel N, Ribes D, Chastre J, Schleinitz N, Veit V, Piette JC, Harlé JR, Combes A, Amoura Z (2017) Lupus myocarditis: initial presentation and long-term outcomes in a multicentric series of 29 patients. J Rheumatol 44:24–32. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160493

Frustaci A, Gentiloni N, Caldarulo M (1996) Acute myocarditis and left ventricular aneurysm as presentations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Chest 109:282–284

Ueda T, Mizushige K, Aoyama T, Tokuda M, Kiyomoto H, Matsuo H (2000) Echocardiographic observation of acute myocarditis with systemic lupus erythematosus. Jpn Circ J 64:144–146

Tamburino C, Fiore CE, Foti R, Salomone E, di Paola R, Grimaldi DR (1989) Endomyocardial biopsy in diagnosis and management of cardiovascular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Clin Rheumatol 8:108–112

Sherer Y, Levy Y, Shoenfeld Y (1999) Marked improvement of severe cardiac dysfunction after one course of intravenous immunoglobulin in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 18:238–240

Wang H, Guo X, Lai J, Wang Q, Tian Z, Liu Y, Li M, Zhao J, Zeng X, Fang Q (2016) Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin Exp Rheumatol 34:291–295

Qian J, Wang Y, Huang C, Yang X, Zhao J, Wang Q, Tian Z, Li M, Zeng X (2016) Survival and prognostic factors of systemic lupus erythematosus-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev 15:250–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2015.11.012

Apte M, McGwin G Jr, Vila LM et al (2008) Associated factors and impact of myocarditis in patients with SLE from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LV). [corrected]. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47:362–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kem371

Funding

This study was funded by the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (Grant No. SZSM201612080).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/ or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, E., Geng, H., Liu, Q. et al. Cardiac manifestations of Han Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a retrospective study. Ir J Med Sci 188, 801–806 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1934-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-018-1934-7