Abstract

Trichome-based tomato resistance offers the potential to reduce pesticide use, but its compatibility with biological control remains poorly understood. We evaluated Episyrphus balteatus De Geer (Diptera, Syrphidae), an efficient aphidophagous predator, as a potential biological control agent of Myzus persicae Sulzer (Hemiptera, Aphididae) on trichome-bearing tomato cultivars. Episyrphus balteatus’ foraging and oviposition behavior, as well as larval mobility and aphid accessibility, were compared between two tomato cultivars (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. ‘Moneymaker’ and ‘Roma’) and two other crop plants; broad bean (Vicia faba L.) and potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Hoverfly adults landed and laid more eggs on broad beans than on three species of Solanaceae. Hoverfly larval movement was drastically reduced on tomato, and a high proportion of hoverfly larvae fell from the plant before reaching aphid prey. After quantifying trichome abundance on each of these four plants, we suggest that proprieties of the plant surface, specifically trichomes, are a key factor contributing to reduced efficacy of E. balteatus as a biological agent for aphid control on tomatoes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aphids are major agricultural and horticultural pests throughout the world. While they can result in direct damage to crops through feeding on phloem tissue, they can also contribute to severe indirect damage by acting as primary vectors of many plant viruses. Aphids reproduce rapidly and have been shown to adapt quickly to host-plant phenology and ecology, as well as plant physiology and biochemistry (e.g. Pettersson et al. 2007).

While chemical insecticides can provide adequate control of aphid populations, increased resistance among aphid populations to chemical products highlights the need for alternative control methods, including the use of natural enemies (Cook et al. 2007). In order to increase the effectiveness of such alternative control techniques we need a better understanding of the ecology and behavior within these tri-trophic interactions.

Aphid communities are subject to predation by a broad range of specialist and generalist arthropod predators and parasitoids. Aphid natural enemies such as hoverflies (Gilbert 1986, 2005), coccinellid beetles (Hodek and Honek 1996), lacewings (Principi and Canard 1984), cecidomyiid midges (Nijveldt 1988), spiders (Sunderland et al. 1986) and parasitoids (Stáry 1970), are major components of the natural enemy guild associated with aphid colonies. Hoverflies are efficient aphidophagous predators (Alhmedi et al. 2008). Our study organism, Episyrphus balteatus De Geer (Diptera, Syrphidae), is an economically important syrphid and accepts a broad range of aphid species in the field (e.g. Völkl et al. 2007). Whereas adult hoverflies feed on nectar, pollen, plant saps, and aphids’ honeydew, the larvae of this species are voracious predators of aphids and are important biological control agents (e.g. Ankersmit et al. 1986; Chambers and Adams 1986). The complete ventral body side of apodal larvae adheres closely to plant surfaces by greasy smeared saliva. Larvae move by means of body contractions (e.g. Bathia 1939; Brauns 1953; Roberts 1971; Gries 1986; Rotheray 1987). Adults’ tarsi are equipped with paired curved claws interlocking with rough surfaces; and additionally, they bear two pulvilli covered with adhesive setae adhering to smooth surfaces (Gorb et al. 2001). Attachment and locomotion are influenced by plant surface qualities and probably important features for prey searching efficiency (Rotheray 1987).

Most predators have been shown to have specific host plant preferences (e.g. Hodek 1993; Schoonhoven et al. 1998; Almohamad et al. 2007, 2008a), and these preferences need to be considered when exploiting them as biological control agents. These preferences are especially important for syrphids because syrphid larvae have limited dispersal abilities (Chandler 1969). Therefore oviposition site discrimination has a strong impact on offspring performance (Scholz and Poehling 2000). The oviposition preference of female syrphids has recently been correlated with offspring performance on preferred host plants (Almohamad et al. 2007). The behavioural impact of various plant and prey secondary metabolites, including volatile and non-volatile chemicals, in the localization and selection of an oviposition site in E. balteatus has largely been demonstrated (Chandler 1968; Kan 1988; Sadeghi and Gilbert 2000a, b; Harmel et al. 2007; Almohamad et al. 2008b; Verheggen et al. 2008). Among these chemicals, the main component of the aphid alarm pheromone, the sesquiterpene (E)-β-farnesene (Francis et al. 2005a), acts as an attractant and an oviposition stimulant for various aphid predators including the ladybeetle Harmonia axyridis Pallas and the hoverfly E. balteatus (Almohamad et al. 2007, 2008b; Verheggen et al. 2007, 2008, 2009).

While previously studying induced volatile emissions of aphid-infested tomato plants, and the subsequent effect on E. balteatus attraction, we observed their apparent failure in aphid control on tomato plants. We therefore estimated in the present study the ability of hoverfly females to orient toward and forage on glandular hairy tomato plants infested by M. persicae. We evaluated E. balteatus as a possible biological agent against aphids on tomato compared to potato and broad bean plants. Surfaces of Lycopersicon sp. and Solanum sp. have been reported to be covered with glandular trichomes (e.g. Luckwill 1943; Gibson 1971), whereas the surface of V. faba appears to be glabrous (Hessayon 2003). We observed (1) the host plant preference of female hoverflies considering searching, selection and oviposition behavior as well as (2) the larval locomotion on different plant surfaces.

Trichome-mediated plant defenses are implicated in both the second and the third trophic level (see the review of Kennedy 2003). First, trichomes can provide major resistance against a number of herbivorous arthropods like aphids (Farrar and Kennedy 1991; Simmons et al. 2003), but can also interact directly or indirectly with their natural enemies (Kennedy 2003). The resulting effects might be positive (increased proliferation, decreased cannibalism) (e.g. Seagraves and Yeargan 2006) or negative (impeded searching behavior, lower prey accessibility) (e.g. Obrycki and Tauber 1984; Oku et al. 2006; Economou et al. 2006). Particularly, the presence and density of trichomes have been previously considered to affect insects (e.g. Levin 1973). Both adults and larvae of hoverflies have been reported to be more abundant and better suited to exploiting aphids on smooth, flat surfaces (e.g. Rotheray 1987; Wnuk and Gospodarek 1999; Sadeghi and Gilbert 2000a, b). During centrifugal force experiments, adult E. balteatus generated attachment forces on smooth PVC surfaces enabling them to withstand acting centrifugal forces up to the twentyfold of their body weight (20 mg) (Gorb et al. 2001). On hairy leaves of cucumber, bean, and tomato, the mobility of syrphid larvae has been observed to be considerably decreased (Albert et al. 2007). To test the hypothesis that trichome density plays an important role for the predatory success of syrphids on plants, we counted trichomes per unit area of stems, and discussed these data related to obtained observational results.

Materials and methods

Plants and insects

Two tomato cultivars Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. ‘Moneymaker’ and ‘Roma’ (Solanaceae), whose aphid infestations were previously observed to be hardly controlled while using predatory hoverflies (Verheggen, unpublished data), were selected to test larval locomotion and success in reaching aphid colonies. Two additional host plants of Myzus persicae Sulzer (Homoptera, Aphididae), namely broad bean Vicia faba L. ‘Grosse ordinaire’ (Fabaceae) and potato Solanum tuberosum L. ‘Bintje’ (Solanaceae), were selected for comparison with the above mentioned tomato cultivars. Vicia faba and S. tuberosum were chosen because they were shown in previous work to be easily exploited as host plants by E. balteatus (Almohamad et al. 2007; Harmel et al. 2007), and they have different surface proprieties compared to tomato cultivars.

Broad beans were grown in 30 × 20 × 5 cm plastic trays filled with a mix of perlite and vermiculite (1:1). Potato and tomato plants were cultivated in 8 × 8 × 10 cm plastic pots filled with a mix of compost, perlite, and vermiculite (1:1:1). All plants were grown in controlled environment growth rooms (16:8 h light:dark; 20 ± 2°C; RH: 70 ± 5%). The peach aphids were reared on the four previously mentioned plants in separate controlled environment growth rooms set at the same conditions as described above. Adult specimens of E. balteatus were reared in a separate room, in 75 × 60 × 90 cm cages and were fed with bee pollen, sugar and water. Broad beans infested with M. persicae were introduced into the cages for 3 h every 2 days to allow oviposition by hoverfly adults. Hatched hoverfly larvae were mass-reared in aerated plastic boxes (110 × 140 × 40 mm) and were fed daily ad libitum with M. persicae as a standard diet. All the hoverfly adults tested in the following experiments were 2–4 weeks old, which corresponds to sexual maturity and high fecundity (Sadeghi and Gilbert 2000c), and had not previously been exposed to aphid-infested plants.

Host plant preference of female hoverflies

In no-choice experiments, hoverfly females were individually placed in screened cages (30 × 30 × 60 cm) with one of the four tested plant species infested with 100 adult M. persicae 24 h prior to observations. Plants, roughly 20 cm tall, having four fully expanded leaves were presented in a plastic pot filled with the same soil composition as presented above. The soil was covered with aluminum foil to avoid any volatile chemicals released by the compost to affect the hoverfly behavior. The hoverfly foraging behavior was visually observed and recorded for 10 min using the Observer® software (Noldus Information Technology, version 5.0, Wageningen, The Netherlands). Descriptions of the five observed behavioral subdivisions (Immobility, Flying, Searching, Acceptance, Oviposition) are presented in Table 1.

In another series of similar no-choice experiments, single E. balteatus females were allowed to lay eggs for 3 h and the number of eggs laid on each aphid infested plant was counted. The experiments were conducted at a controlled temperature of 20 ± 2°C, and relative humidity of 70 ± 5%. E. balteatus females were 21–28 days old. One female per each plant was tested. There were a total of 20 replicates for each of the two aforementioned experiments.

Observation of larval locomotion

In above mentioned net cages, 20 cm tall plants were infested by placing 20 adult M. persicae on the adaxial surface of two fully expanded leaves. All other lower leaves were manually removed from the plant. Aphids were allowed to feed 4 h before starting the experiment. After this initial aphid settlement period a third instar larva of E. balteatus, starved 5 h prior to the experiment, was placed in the middle of the plant on the stem, oriented to face the top of the plant. Twenty hoverfly larvae were observed separately on 20 individual plants per each of the four above mentioned test plants. Three types of reactions were observed ocularly and recorded: (1) When a larva moved and reached the top of the plant within 15 min of placement on the plant, (2) when a larva fell from the plant within 15 min of placement on the plant, and (3) when a larva remained stationary or did not reach the top of the plant within the 15 min of observation. Each plant and insect was tested once.

The average larval locomotion speed was calculated by taking into account the larvae that reached the top of the plant within the 15 min of observation. Larval locomotion speed (mm s−1) was calculated as the distance traveled divided by the time needed to reach the top of the plant.

Evaluation of trichome density

To correlate the impact of trichome density with the host plant preference of female, and with the locomotion speed of larval hoverflies, we quantified the trichome density by counting the number of trichomes per square centimeter of stem surface under the binocular microscope Olympus® SZ40 (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Digital images were taken using a Canon® 450D equipped with a 100 mm f2.8 Canon® macro lens (Canon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). A 1 cm long piece of the stem was cut with a razor blade from the middle of a 20 cm tall plant with four fully expanded leaves. Ten plants of each of the four tested cultivars were cut this way. According to Luckwill (1943) and Simmons and Gurr (2005), there are up to five types of glandular and non-glandular trichomes found on a L. esculentum (named types I, III, V, VI, VII). Glandular trichomes have ‘heads’ that release, on contact with pests, sticky and/or toxic exudates that entrap, irritate and potentially kill the pest. Non-glandular trichomes have no ‘heads’ releasing sticky and/or toxic exudates and may affect pests by mechanical means (e.g. constituting a barrier to movement or access to nutritious source(s)) (Simmons and Gurr 2005). We considered only trichomes of types I and III reaching a length of 1.0–2.5 mm for the determination of trichome density. In S. tuberosum, all trichomes of more than 1.0 mm were counted. Indeed, according to our observations, no contact occurred between the body of the tested third instar hoverfly larvae (being usually larger than 7 mm) and the smallest trichomes of types V, VI and VII, ranging from 0.05 to 0.5 mm (Fig. 1).

Digital images of third instar hoverfly larvae moving on the glandular hairy stem surface of Lycopersicon esculentum ‘Moneymaker’, showing two different positions of the locomotion process. Larvae adhere to the tips of long trichomes, without direct contact between the insect body and the solid stem surface

Statistical analyses

One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (pairwise comparisons) were used to evaluate data obtained in the host plant preference experiment (Minitab® release 14.2 software, Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA). A general linear model followed by Tukey’s test (pairwise comparisons) was used to compare the average larval locomotion speed observed on the four tested host plants.

Results

Host plant preference of female hoverflies

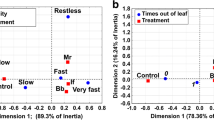

In no-choice experiments, the relative durations of the five observed behavioral subdivisions (Immobility, Flying, Searching, Acceptance, Oviposition) were recorded. Relative durations of the ‘Immobility’ and ‘Searching’ behavior were similar for the four plants tested (ANOVA, Tukey post-hoc test, P > 0.05). However, hoverfly females spent more of their time (recorded as acceptance) on V. faba than on S. tuberosum and L. esculentum ‘Moneymaker’ (ANOVA, F 3,76 = 4.66, P = 0.005, Tukey post-hoc test) (Fig. 2). In addition, the relative duration spent ovipositing on broad bean plants was greater than on the three species of Solanaceae (ANOVA, F 3,76 = 6.50, P = 0.001, Tukey post-hoc test). These observations are in accordance with the number of eggs laid on each of the four tested plants. An average (± SE) of 28.65 ± 5.48 eggs were laid on V. faba. Significantly fewer eggs were laid on S. tuberosum and L. esculentum ‘Roma’ and ‘Moneymaker’, with 8.95 ± 2.69, 11.80 ± 2.60 and 10.75 ± 3.69 eggs respectively (mean ± SE) (ANOVA, F 3,76 = 5.81, P = 0.001, Tukey post-hoc test).

Host plant preference of Episyrphus balteatus females in no-choice experiments with four different aphid-infested host plants indicated by behavioural characteristics (% of the 10 min total observation time + SE). Different letters indicate significant differences between plant species and cultivars for a single behaviour characteristic (n = 20; for detailed statistical values see results section)

Larval locomotion

To evaluate the ability of E. balteatus larvae to reach their aphid prey, their locomotion was observed, and the locomotion speed was recorded on each of the four plants was recorded (Fig. 3). Only the larvae that reached the top of the plant within the 15 min of observation were taken into account in the calculation of the average larval locomotion speed: 11, 10, 4, and 5 larvae for V. faba, S. tuberosum, L. esculentum ‘Roma’ and ‘Moneymaker’ respectively. The average (± SE) locomotion speed of hoverfly larvae on V. faba (2.7 ± 0.37 mm s−1) was significantly higher than on both tomato cultivars, ‘Roma’ (0.8 ± 0.33 mm s−1) and ‘Moneymaker’ (0.7 ± 0.23 mm s−1) (ANOVA, F 3,26 = 4.23, P = 0.015, Tukey post-hoc test). The average (± SE) larval speed on S. tuberosum (1.44 ± 0.47 mm s−1) did not differ significantly from the speed values on the three other aphid host plants tested. In addition, the number of larvae that fell from the plant was counted. No larvae fell from V. faba and one larva fell from S. tuberosum. On L. esculentum, 50% (‘Roma’) and 25% (‘Moneymaker’) of the larvae fell while walking on the glandular hairy plant surface.

Trichome density

While no trichomes were found on the plant surface of V. faba, an average (± SE) of 16.84 ± 2.08 trichomes were present per cm2 of S. tuberosum stem. L. esculentum ‘Moneymaker’ and ‘Roma’ had 68.32 ± 5.31 and 72.32 ± 5.46 trichomes (mean ± SE, types I and III pooled together) per cm2 of stem, respectively (Fig. 4). Trichome densities were significantly different between S. tuberosum and both L. esculentum cultivars, but not between the two tomato cultivars (ANOVA, F 2,27 = 46.01, P < 0.001, Tukey post-hoc test).

Discussion

Insect–plant interactions involving the genus Lycopersicon, their herbivores and herbivore natural enemies have been previously studied by several authors, and reviewed by Kennedy (2003). Beside the beneficial impact of their volatile chemicals on infesting pests (Ecole et al. 2001), trichome-based natural resistance of tomato plants offers a potential approach to reduce pesticide use (McKinney 1938). Trichomes are usually implicated in the second trophic level by increasing pest mortality, as demonstrated within numerous host plant models including tomatoes (e.g. Johnson 1956; Musetti and Neal 1997) and potatoes (e.g. Gibson 1971, 1974). For example, the glandular trichomes of the wild potato species, Solanum berthaultii Hawkes, deter oviposition and affect other important performance parameters of the potato tuber moth, Phthorimaea operculella Zeller (Lepidoptera, Gelechiidae) (Malakar and Tingey 2000). The feeding behavior of the potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae Th. (Hemiptera, Aphididae) was deterred by glucose esters present in glandular trichome exudates of the wild tomato, Lycopersicon pennellii Corr. (D’Arcy) (Goffreda et al. 1989). However, the compatibility of trichome abundance with biological control agents remains sometimes unclear, although it is well known that they are also implicated in the third trophic level. Indeed, trichomes affect natural enemies either by direct contact or indirectly by positively affecting the phytophagous prey insect (e.g. Simmons et al. 2003; Oku et al. 2006). However, interactions between plant surfaces and hoverfly aphidophagous predators have previously received little attention.

When looking for suitable oviposition sites, hoverfly females are able to discriminate between aphid species as well as between host plants on the basis of the released odorant cues (Bargen et al. 1998; Almohamad et al. 2007; Verheggen et al. 2008). When landed on a plant, hoverflies use tactile foraging, through extension of their proboscis, before laying their eggs. Broad beans, V. faba, have been largely used in the study of the oviposition behavior of hoverflies, demonstrating its suitability for this aphidophagous predator within pest management strategies (e.g. Vanhaelen et al. 2001; Francis et al. 2005b; Verheggen et al. 2008). Potatoes have also been presented as suitable host plants for hoverfly female oviposition (e.g. Verma et al. 2005; Harmel et al. 2007; Almohamad et al. 2007). In our behavioral experiments, the negative effect of trichomes on the accessibility of hoverfly adults was visually observed. In no choice experiments, we showed that E. balteatus females were landing and laying eggs more frequently on V. faba rather than on the three Solanaceae studied, which is likely to lead to a more efficient foraging of aphid preys. Our findings correspond to observations of previous authors who reported higher abundance of hoverflies on V. faba and other plants having non-hairy surface compared to these ones with trichome coverage (e.g. Wnuk and Gospodarek 1999). Although hoverfly females were flying close to tomato plants (see “searching behavior” in Fig. 1), they had clear difficulties in landing, presumably due to the presence of long trichomes of types I and III.

Increased trichome density can reduce aphid accessibility, but can also affect negatively predator efficacy through increased predator cannibalism, predator mortality due to entrapment by trichomes or falling off the plant. Accordingly, the ability of the lacewings Mallada signata Schneider (Neuroptera, Chrysopidae) to be used as biological control agents against aphids on pubescent tomato plants has been questioned in previous work, showing that densely arranged trichomes cause a decreasing number of predated aphids and increased cannibalism and entrapment-related predator mortality (Simmons and Gurr 2004). The presence of trichomes is also known to reduce the residence time and foraging efficiency of larval lacewings Chrysoperla spp. (Neuroptera, Chrysopidae), which are further representatives of components of the aphid predatory guild (Gassman and Hare 2005). Two other aphid predators, Macrolophus pygmaeus Rambur (Heteroptera, Miridae) and Orius niger Wolff (Heteroptera, Anthocoridae), have been also reported to be negatively influenced by the density of glandular trichomes on the surface of tomato plants (Economou et al. 2006). The bugs spent most of their time grooming instead of searching for prey because they were in touch with exudates that accumulated on their tarsi. Orius insidious Say, a mite predator, has shown also greater foraging ability on smooth plant surfaces than on tomato plant (Coll et al. 1997).

Trichome density on the stem surface of tomatoes has also an influence on the foraging speed of hoverfly larvae. Many larvae fell while trying to reach the top aphid-infested leaves of tomato plants, supporting previous observations of a considerably decreased mobility of syrphid larvae on hairy leaves cucumber, bean, and tomato (Albert et al. 2007). While no information on larval mobility has been reported for Solanum sp., the hoverfly larvae have been shown to have strong predatory potential on these plant species (Verma et al. 2005). Although the locomotion of hoverfly larvae was observed to be reduced on potato (compared to broad beans) obviously because of its pubescence, the locomotion speed did not statistically differ, and only one of the 20 hoverfly larvae tested on S. tuberosum fell from the plant. Entomophagous insects (Coccinellidae, Chrysopidae, Thripidae, Anthocoridae, parasitoids) have been widely reported to be hampered by pubescent plant surfaces in numerous publications (e.g. Putman 1955; Rabb and Bradley 1968; Shah 1982). However, these results contrast with those obtained in studies of specialized predators like fire ants of the species Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) (Styrsky et al. 2006) and the coccinellid Coleomegilla maculata DeGeer (Coleoptera, Coccinellidae) (Seagraves and Yeargan 2006). The latter prefers to oviposit on plants having glandular trichomes that would provide the eggs a refuge from cannibalism and other predation. The omnivorous mirid bug Dicyphus errans Wolff (Heteroptera, Miridae) preys on a variety of phytophagous arthropods living on pubescent plants that provide the bug stronger attachment and therefore more reliable locomotion as well as more successful oviposition and predation (Voigt et al. 2007). The contrary observations realized in our study with E. balteatus may be caused by different morphological features. Unlike above mentioned predators, syrphid larvae do not bear long articulating legs.

Although apodal syrphid larvae are known to form a close contact with glabrous plant surface (e.g. Brauns 1953; Wyss 2004), we observed larvae of E. balteatus somehow moving along tips of long trichomes on the surface of tomato stems. However, compared to the smooth surface f broad beans, larval attachment and mobility were strongly limited by the abundance of trichomes in Solanaceae. But furthermore, the type, arrangement, dispersion, anatomy properties, and geometrical variables of trichomes may influence insect attachment to and locomotion on plant surfaces (e.g. Voigt et al. 2007). In particular, sticky exudates of glandular trichomes may contaminate insects (Kennedy 2003; Voigt et al. 2007), which may be also possible in E. balteatus contacting glandular hairy plant surfaces. The effects of trichomes may be more apparent on apodal syrphid larvae than on leg-bearing predators like, e.g. representatives of Heteroptera able to interlock with trichomes using claws, and having distinct distance from the plant surface due to their long legs. However, in both females and apodal larvae of the predatory midge Aphidoletes aphidimyza Rondani (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae), which larvae have similar locomotion and foraging strategies like those of syrphids, the higher density of trichomes, the more eggs were laid and the more egg survival was observed (Lucas and Brodeur 1999). But compared to syrphid larvae, predatory midges have a distinctly smaller body size, possibly enabling them to move easily on the smooth patches of the plant surface between trichomes. In contrast, larger syrphid larvae, contacting only trichome tips, may be affected by the larger trichomes that act as a hurdle for larval locomotion.

Our results show that the plant surfaces covered densely with trichomes are not suitable for both hoverfly female and larva foraging, although no statistical regressions have been carried out. We showed that the attachment and locomotion of the predatory larvae of E. balteatus is compromised on solanaceous plants densely covered with glandual trichomes, particularly on L. esculentum cultivars. Therewith, larval mobility and subsequent aphid accessibility are decreased. However, trichome density does not seem to be the single hampering plant surface feature for syrphid access, which should be analysed in further studies.

References

Albert R, Allgaier C, Schneller H, Schrameyer K (2007) Biologischer Pflanzenschutz im Gewächshaus. Eugen Ulmer KG, Stuffgart, p 94

Alhmedi A, Haubruge E, Francis F (2008) Role of prey-host plant associations on Harmonia axyridis and Episyrphus balteatus reproduction and predatory efficiency. Entomol Exp Appl 128:49–56

Almohamad R, Verheggen FJ, Francis F, Haubruge E (2007) Predatory hoverflies select their oviposition site according to aphid host plant and aphid species. Entomol Exp Appl 125:13–21

Almohamad R, Verheggen FJ, Francis F, Hance T, Haubruge E (2008a) Discrimination of parasitized aphids by an hoverfly predator: effect on larval performance, foraging and oviposition behavior. Entomol Exp Appl 128(1):73–80

Almohamad R, Verheggen FJ, Francis F, Lognay G, Haubruge E (2008b) Emission of alarm pheromone by non-preyed aphid colonies. J Appl Entomol 132:601–604

Ankersmit GW, Dijkman H, Keuning NJ, Mertens H, Sins A, Tacoma H (1986) Episyrphus balteatus as a predator of the aphid Sitobion avenae on winter wheat. Entomol Exp Appl 42:271–277

Bargen H, Saudhof K, Poehling H-M (1998) Prey finding by larvae and adult females of Episyrphus balteatus. Entomol Exp Appl 87:245–254

Bathia ML (1939) Biology, morphology and anatomy of aphidophagous syrphid larvae. Parasitology 31:78–129

Brauns A (1953) Beitrage zur Oekologie und wirtschaftlichen Bedeutung der aphidivoren Syrphidenarten. Beitr Ent 3:278–303

Chambers RJ, Adams THL (1986) Quantification of the impact of hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) on cereal aphids in winter wheat: an analysis of field populations. J Appl Ecol 23:895–904

Chandler AEF (1968) Some host plant factors affecting oviposition by aphidophagous Syrphidae. Ann Appl Biol 61:415–423

Chandler AEF (1969) Locomotive behavior of first instar larvae of aphidophagous Syrphidae (Diptera) after contact with aphids. Anim Behav 17:673–678

Coll M, Smith LA, Ridgway RL (1997) Effect of plants on the searching efficiency of a generalist predator: the importance of predator-prey spatial association. Entomol Exp Appl 83:1–10

Cook SM, Khan ZR, Pickett JA (2007) The use of Push-Pull strategies in integrated pest management. Annu Rev Entomol 52:375–400

Ecole CC, Picanco MC, Guedes RNC, Brommonschenkel SH (2001) Effect of cropping season and possible compounds involved in the resistance of Lycopersicon hirsutum f. typicum to Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lep., Gelechiidae). J Appl Entomol 125:193–200

Economou LP, Lykouressis DP, Barbetaki AE (2006) Time allocation of activities of two heteropteran predators on the leaves of three tomato cultivars with variable glandular trichome density. Environ Entomol 35:387–393

Farrar RR, Kennedy GG (1991) Insect and mite resistance in tomato. In: Kalloo G (ed) Genetic improvement of tomato. Monographs on theoretical and applied genetics, vol 14. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 121–142, 358 pp

Francis F, Vandermoten S, Verheggen F, Lognay G, Haubruge E (2005a) Is the (E)-B-farnesene only volatile terpenoid in aphids? J Appl Entomol 129:6–11

Francis F, Martin T, Lognay G, Haubruge E (2005b) Role of (E)-b-farnesene in systematic aphid prey location by Episyrphus balteatus larvae (Diptera, Syrphidae). Eur J Entomol 102:431–436

Gassman AJ, Hare JD (2005) Indirect cost of a defensive trait: variation in trichome type affects the natural enemies of herbivorous insects on Datura wrightii. Oecologia 144:62–71

Gibson RW (1971) Glandular hairs providing resistance to aphids in certain wild potato species. Ann Appl Biol 68:113–119

Gibson RW (1974) Aphid-trapping glandular hairs on hybrids of Solanum tuberosum and S. berthaultii. Potato Res 17:152–154

Gilbert FS (1986) Hoverflies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 66 pp

Gilbert FS (2005) Syrphid aphidophagous predators in a food-web context. Eur J Entomol 102:325–333

Goffreda JC, Mutschler MA, Avé DA, Tingey WM, Steffens JC (1989) Aphid deterrence by glucose esters in glandular trichome exudates of the wild tomato, Lycopersicon pennillii. J Chem Ecol 15:2135–2147

Gorb S, Gorb E, Kastner V (2001) Scale effects on the attachment pads and friction forces in syrphid flies (Diptera, Syrphidae). J Exp Biol 204:1421–1431

Gries G (1986) Zum Beutefangverhalten der Schwebfliegenlarve Syrphus balteatus Deg. (Diptera, Syrphidae). J Appl Entomol 102:309–313

Harmel N, Almohamad R, Fauconnier M-L, Du Jardin P, Verheggen F, Marlier M, Haubruge E, Francis F (2007) Role of terpenes from aphid-infested potato on searching and oviposition behavior of the hoverfly predator Episyrphus balteatus. Insect Sci 14:57–63

Hessayon DG (2003) The vegetable and herb expert. Expert Books, 128 pp

Hodek I (1993) Habitat and food specificity in aphidophagous predators. Biocontrol Sci Technol 3:91–100

Hodek I, Honek A (1996) Ecology of the Coccinellidae. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 464 pp

Johnson B (1956) The influence on aphids of the glandular hairs of tomato plants. Plant Pathol 5:131–132

Kan E (1988) Assessment of aphid colonies by hoverflies. I Maple aphids and Episyrphus balteatus (De Geer) (Diptera: Syrphidae). J Ethol 6:39–48

Kennedy GG (2003) Tomato, pests, parasitoids, and predators: trophic interactions involving the genus Lycopersicon. Annu Rev Entomol 48:51–72

Levin DA (1973) The role of trichomes in plant defence. Q Rev Biol 48:3–15

Lucas E, Brodeur J (1999) Oviposition site selection by the predatory midge Aphidoletes aphidimyza (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae). Environ Entomol 28:622–627

Luckwill LC (1943) The genus Lycopersicon: an historical, biological and taxonomic survey of the wild and cultivated tomatoes. Aberdeen University Studies number 120. Aberdeen University Press, Aberdeen, 44 pp

Malakar R, Tingey WM (2000) Glandular trichomes of Solanum berthaultii and its hybrids with potato deter oviposition and impair growth of potato tuber moth. Entomol Exp Appl 94:249–257

McKinney KB (1938) Physical characteristics on the foliage of beans and tomatoes that tend to control some small insect pests. J Econ Entomol 31:630–631

Musetti L, Neal JJ (1997) Resistance to the pink potato aphid, Macrosiphum euphorbiae, in two accessions of Lycopersicon hirsutum f. glabratum. Entomol Exp Appl 84:137–146

Nijveldt W (1988) Cecidomyiidae. In: Minks AK, Harrewijn P, Helle W (eds) World crop pests, aphids. Elsevier Science, New York, pp 271–277

Obrycki JJ, Tauber MJ (1984) Natural enemy activity on glandular pubescent potato plants in the greenhouse: an unreliable predictor of effects in the field. Environ Entomol 13:679–683

Oku K, Yano S, Takafuji A (2006) Host plant acceptance by the phytophagous mite Tetranychus kanzawai Kishida is affected by the availability of a refuge on the leaf surface. Ecol Res 21:446–452

Pettersson J, Tjallingii WF, Hardie J (2007) Host-plant selection and feeding. In: Van Emden H, Harrington R (eds) Aphids as crop pests. CAB International, Wallingford, pp 87–114

Principi MM, Canard M (1984) Feeding habits. In: Canard M, Semeria Y, New TT (eds) Biology of Chrysopidae. Junk Publishers, The Hague, pp 76–92

Putman WL (1955) Bionomics of Stethorus punctillum Weise (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in Ontario. Can Entomol 86:9–33

Rabb RL, Bradley JR (1968) The influence of host plants on parasitism of eggs of Manduca sexta (Johannsen). J Econ Entomol 61:1249–1252

Roberts MJ (1971) On the locomotion of cyclor-rhaphan maggots (Diptera). J Nat Hist 5:583–590

Rotheray GE (1987) Larval morphology and searching efficiency in aphidophagous syrphid larvae. Entomol Exp Appl 43:49–54

Sadeghi H, Gilbert F (2000a) Aphid suitability and its relationship to oviposition preference in predatory hoverflies. J Anim Ecol 69:771–784

Sadeghi H, Gilbert F (2000b) Oviposition preferences of aphidophagous hoverflies. Ecol Entomol 25:91–100

Sadeghi H, Gilbert F (2000c) The effect of egg load and host deprivation on oviposition behaviour in aphidophagous hoverflies. Ecol Entomol 25:101–108

Scholz D, Poehling H-M (2000) Oviposition site selection of Episyrphus balteatus. Entomol Exp Appl 92:149–158

Schoonhoven LM, Jermy T, Van Loon JJA (1998) Insect-plant biology: from physiology to evolution. Chapman and Hall, London, 409 pp

Seagraves MP, Yeargan KV (2006) Selection and evaluation of a companion plant to indirectly augment densities of Coleomegilla maculata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in sweet corn. Environ Entomol 35:1334–1341

Shah MA (1982) The influence of plant surfaces on the searching behaviour of coccinellid larvae. Entomol Exp Appl 31:377–380

Simmons AT, Gurr GM (2004) Trichome-based host plant resistance of Lycopersicon species and the biocontrol agent Mallada signata: are they compatible? Entomol Exp Appl 113:95–101

Simmons AT, Gurr GM (2005) Trichomes of Lycopersicon species and their hybrids: effects on pests and natural enemies. Agric For Entomol 7:265–276

Simmons AT, Gurr GM, McGrath D, Nicol HI, Martin PM (2003) Trichomes of Lycopersicon spp. and their effect on Myzus persicae. Aust J Entomol 42:373–378

Stáry P (1970) Biology of aphid parasites, with respect to integrated control. Junk Publishers, The Hague, 641 pp

Styrsky JD, Kaplan I, Eubanks MD (2006) Plant trichomes indirectly enhance tritrophic interactions involving a generalist predator, the red imported fire ant. Biol Control 36:375–384

Sunderland KD, Fraser AM, Dixon AFG (1986) Field and laboratory studies on money spiders (Linyphilidae) as predators of cereal aphids. J Appl Ecol 23:433–447

Vanhaelen N, Haubruge E, Gaspar C, Francis F (2001) Oviposition preferences of Episyrphus balteatus. Meded Rijksuniv Gent Fak Landbouwkd Toegep Biol Wet 66:269–275

Verheggen FJ, Fagel Q, Heuskin S, Lognay G, Francis F, Haubruge E (2007) Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of the multicolored Asian lady beetle, Harmonia axyridis Pallas, to sesquiterpene semiochemicals. J Chem Ecol 33:2148–2155

Verheggen FJ, Arnaud L, Bartram S, Gohy M, Haubruge E (2008) Aphid and plant secondary metabolites induce oviposition in an aphidophagous hoverfly. J Chem Ecol 34:301–307

Verheggen FJ, Haubruge E, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC (2009) Social environment influences aphid production of alarm pheromone. Behav Ecol 20:283-288

Verma JS, Sharma KC, Anil S, Meenu S (2005) Biology and predatory potential of syrphid predators on Aphis fabae infesting Solanum nigrum L. J Entomol Res 29:39–41

Voigt D, Gorb E, Gorb S (2007) Plant surface-bug interactions: Dicyphus errans stalking along trichomes. APIS 1:221–243

Völkl W, Mackauer M, Pell JK, Brodeur J (2007) Predators, parasitoids and pathogens. In: van Emden H, Harrington R (eds) Aphids as crop pests. CAB International, Wallingford, pp 187–234

Wnuk A, Gospodarek J (1999) Occurrence of aphidophagous Syrphidae (Diptera) in colonies of Aphis fabae Scop., on its various host plants. Ann Agric Sci E 28:7–12

Wyss U (2004) Lebensweise und Entwicklung der Schwebfliege Episyrphus balteatus. Videodocumentation 13 min. www.entofilm.com

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Yves Brostaux and Adeline Gillet, from Gembloux Agricultural University for their advice on statistical analysis. We also thank the three anonymous reviewers for the many useful comments they provided to an earlier version of this manuscript. This work was supported by the Fond National pour la Recherche Scientifique (F.N.R.S., grant M 2.4.586.04.F).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling editor: Stanislaw Gorb

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Verheggen, F.J., Capella, Q., Schwartzberg, E.G. et al. Tomato-aphid-hoverfly: a tritrophic interaction incompatible for pest management. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 3, 141–149 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-009-9065-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-009-9065-8