Abstract

Sleep disturbance is common among women with breast cancer and is associated with greater symptom distress and poorer outcomes. Yet, for the unique subgroup of young women with breast cancer (YWBC), there is limited information on sleep. To address the gap in our understanding of sleep health in YWBC, we explored their perspective on sleep quality, sleep changes over time, contributing factors, and any strategies used to promote sleep. As part of an explanatory sequential mixed method study, we recruited a sub-sample of 35 YWBC (≤ 50 years of age at the time of diagnosis) from the larger quantitative study phase. These participants were within the first 5 years since diagnosis and completed primary and systemic adjuvant therapy. We conducted virtual semi-structured interviews, transcribed them verbatim, and analyzed data with an interpretive description approach. YWBC experience difficulty falling asleep, waking up at night, and not feeling refreshed in the morning. They attributed interrupted sleep to vasomotor symptoms, anxiety/worry, ruminating thoughts, everyday life stressors, and discomfort. The sleep disturbance was most severe during and immediately after treatment but persisted across the 5 years of survivorship. The participants reported trying pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic strategies to improve the quantity and quality of their sleep. Future research would benefit from longitudinal designs to capture temporal changes in sleep and develop interventions to improve sleep health. Clinically, assessment of sleep health is indicated for YWBC related to the prevalence of disturbed sleep.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Early access to sleep assessment and management, ideally before cancer treatment, would be beneficial for young breast cancer survivors. In addition, cancer treatment plans should include physical and psychological symptoms, especially those reported by women in this study: vasomotor symptoms, anxiety and worry, discomfort, and pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy considerations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ellington TD, et al. Trends in breast cancer incidence, by race, ethnicity, and age among women aged≥ 20 years—United States, 1999–2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(2):43.

DeSantis CE, et al. Breast cancer statistics. CA: A Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):438–51.

Assi HA, et al. Epidemiology and prognosis of breast cancer in young women. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(Suppl 1):S2–8.

Champion VL, et al. Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2237–46.

Sanford SD, et al. Symptom burden among young adults with breast or colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2255–63.

Cleeland CS, et al. The symptom burden of cancer: evidence for a core set of cancer-related and treatment-related symptoms from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns study. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4333–40.

Van Onselen C, et al. Trajectories of sleep disturbance and daytime sleepiness in women before and after surgery for breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(2):244–60.

Otte JL, et al. Prevalence, severity, and correlates of sleep-wake disturbances in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(3):535–47.

Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Fatigue, sleep, and circadian rhythms prior to chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(3):201–9.

Sanford SD, et al. Longitudinal prospective assessment of sleep quality: before, during, and after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(4):959–67.

Beverly CM, et al. Change in longitudinal trends in sleep quality and duration following breast cancer diagnosis: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2018;4(1):15.

Lowery-Allison AE, et al. Sleep problems in breast cancer survivors 1–10 years posttreatment. Palliat Support Care. 2018;16(3):325–34.

Hwang Y, Knobf M. Sleep health in young women with breast cancer: a narrative review. Supportive Care Cancer. 2022;30(8):6419–28.

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications; 2017. p. 521.

Curry LA, Nunez-Smith M. Mixed methods in health sciences research: a practical primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2015.

Hwang Y, et al. Factors associated with sleep health in young women after breast cancer treatment. Res Nurs Health. 2022;45(6):680–92.

Thorne S. Interprative description: qualitatvie research for applied practice. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2008.

Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Methods. 2004;3(1):1–11.

Buysse DJ, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

Fetters MD. The mixed methods research workbook: activities for designing, implementing, and publishing projects, vol. 7. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2019.

Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–60.

Thorne S. The great saturation debate: what the “S word” means and doesn’t mean in qualitative research reporting. Can J Nurs Res. 2020;52(1):3–5.

Thorne S. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice. Routledge; 2016.

Elliott R, Timulak L. Why a generic approach to descriptive-interpretive qualitative research? In: Elliott R, Timulak L, editors. Essentials of descriptive-interpretive qualitative research: a generic approach. American Psychological Association; 2021. p. 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000224-001

Creswell JW, Báez JC. 30 essential skills for the qualitative researcher. Sage Publications; 2020.

Miles M, Huberman A, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a mehtod sourcebook (fourth edi). Singapour: Sage Publications; 2020.

Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2021;1–440.

Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2018.

Kuckartz U, Rädiker S. Analyzing qualitative data with MAXQDA. Springer; 2019.

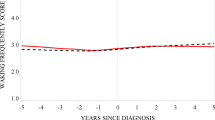

Yang GS, et al. Longitudinal analysis of sleep disturbance in breast cancer survivors. Nurs Res. 2022;71(3):177–88.

Baker FC, et al. Sleep and sleep disorders in the menopausal transition. Sleep Med Clin. 2018;13(3):443–56.

Loprinzi CL, Barton DL, Rhodes D. Management of hot flashes in breast-cancer survivors. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(4):199–204.

Kingsberg SA, Larkin LC, Liu JH. Clinical effects of early or surgical menopause. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(4):853–68.

Kamgar M, et al. Prevalence and predictors of peripheral neuropathy after breast cancer treatment. Cancer Med. 2021;10(19):6666–76.

Smith MT, Haythornthwaite JA. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8(2):119–32.

Gormley M, et al. An integrative review on factors contributing to fear of cancer recurrence among young adult breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2022;45(1):E10-e26.

Takano K, Iijima Y, Tanno Y. Repetitive thought and self-reported sleep disturbance. Behav Ther. 2012;43(4):779–89.

Redeker NS. Social and environmental factors that influence sleep in women, in Reference module in neuroscience and biobehavioral psychology. Elsevier; 2022.

Schutte-Rodin S, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;04(05):487–504.

Sateia MJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(02):307–49.

Zhou ES, et al. Adapting cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia in cancer patients. Sleep Med Res. 2017;8(2):51–61.

Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(2):169–77.

Hunt MR. Strengths and challenges in the use of interpretive description: reflections arising from a study of the moral experience of health professionals in humanitarian work. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(9):1284–92.

Funding

This work was supported by the Global Korean Nursing Foundation and the Sigma Theta Tau International Delta Mu Chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design and material preparation. Data collection and analysis were performed by Youri Hwang and M. Tish Knobf. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Youri Hwang, and all authors reviewed and commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by The Yale University Institutional Review Board and The Yale Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee (HIC #: 2000029349). All participants provided written and verbal informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, Y., Conley, S., Redeker, N.S. et al. A qualitative study of sleep in young breast cancer survivors: “No longer able to sleep through the night”. J Cancer Surviv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01330-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01330-3