Abstract

Purpose

Breast cancer survivorship has improved in recent decades, but few studies have assessed the patterns of employment status following diagnosis and the impact of job loss on long-term well-being in ethnically diverse breast cancer survivors. We hypothesized that post-treatment employment status is an important determinant of survivor well-being and varies by race and age.

Methods

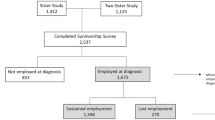

In the Carolina Breast Cancer Study, 1646 employed women with primary breast cancer were longitudinally evaluated for post-diagnosis job loss and overall well-being. Work status was classified as “sustained work,” “returned to work,” “job loss,” or “persistent non-employment.” Well-being was assessed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) instrument. Analysis of covariance was used to evaluate the association between work status and well-being (physical, functional, social, and emotional).

Results

At 25 months post-diagnosis, 882 (53.6%) reported “sustained work,” 330 (20.1%) “returned to work,” 162 (9.8%) “job loss,” and 272 (16.5%) “persistent non-employment.” Nearly half of the study sample (46.4%) experienced interruptions in work during 2 years post-diagnosis. Relative to baseline (5-month FACT-G), women who sustained work or returned to work had higher increases in all well-being domains than women with job loss and persistent non-employment. Job loss was more common among Black than White women (adjusted odds ratio = 3.44; 95% confidence interval 2.37–4.99) and was associated with service/laborer job types, lower education and income, later stage at diagnosis, longer treatment duration, and non-private health insurance. However, independent of clinical factors, job loss was associated with lower well-being in multiple domains.

Conclusions

Work status is commonly disrupted in breast cancer survivors, but sustained work is associated with well-being. Interventions to support women’s continued employment after diagnosis are an important dimension of breast cancer survivorship.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Our findings indicate that work continuation and returning to work may be a useful measure for a range of wellbeing concerns, particularly among Black breast cancer survivors who experience greater job loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Sun Y, Shigaki CL, Armer JM. Return to work among breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(3):709–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3446-1.

Cocchiara RA, Sciarra I, D’Egidio V, Sestili C, Mancino M, Backhaus I, et al. Returning to work after breast cancer: a systematic review of reviews. Work (Reading, Mass). 2018;61(3):463–76. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-182810.

Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid HA, Nahar AM, MohdTaib NA, Su TT. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC public health. 2014;14(Suppl 3):S8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-s3-s8.

Stanton AL, Bower JE. Psychological adjustment in breast cancer survivors. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biol. 2015;862:231–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16366-6_15.

Stafford L, Judd F, Gibson P, Komiti A, Mann GB, Quinn M. Screening for depression and anxiety in women with breast and gynaecologic cancer: course and prevalence of morbidity over 12 months. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22(9):2071–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3253.

Avis NE, Levine B, Naughton MJ, Case LD, Naftalis E, Van Zee KJ. Age-related longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms following breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139(1):199–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2513-2.

Michael YL, Kawachi I, Berkman LF, Holmes MD, Colditz GA. The persistent impact of breast carcinoma on functional health status: prospective evidence from the Nurses’ Health Study. Cancer. 2000;89(11):2176–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11%3c2176::aid-cncr5%3e3.0.co;2-6.PubMedPMID:11147587.

Maunsell E, Drolet M, Brisson J, Brisson C, Masse B, Deschenes L. Work situation after breast cancer: results from a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(24):1813–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djh335.

Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Neumark D. Breast cancer and women’s labor supply. Health services research. 2002;37(5):1309–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.01041.

Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, Davis WW, Brown ML. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(17):1322–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djh255.

Moran JR, Short PF, Hollenbeak CS. Long-term employment effects of surviving cancer. J Health Econ. 2011;30(3):505–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.02.001.

Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo Z, Schenk M. Employment and cancer: findings from a longitudinal study of breast and prostate cancer survivors. Cancer investigation. 2007;25(1):47–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/07357900601130664.

Mahar KK, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Shields JJ. The impact of changes in employment status on psychosocial well-being: a study of breast cancer survivors. J Psychosocial oncology. 2008;26(3):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347330802115400.

Finkelstein EA, Tangka FK, Trogdon JG, Sabatino SA, Richardson LC. The personal financial burden of cancer for the working-aged population. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(11):801–6 (Epub 2009/11/10 PubMed PMID: 19895184).

Guy GP Jr, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, Smith AW, Dowling EC, Rechis R, et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2014;33(6):1024–31. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1425.

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP Jr, Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):259–67. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.62.0468.

Short PF, Vasey JJ, Tunceli K. Employment pathways in a large cohort of adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1292–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20912.

Emerson MA, Golightly YM, Tan X, Aiello AE, Reeder-Hayes KE, Olshan AF, et al. Integrating access to care and tumor patterns by race and age in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study, 2008–2013. Cancer Causes Control. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01265-0.

Ekenga CC, Perez M, Margenthaler JA, Jeffe DB. Early-stage breast cancer and employment participation after 2 years of follow-up: a comparison with age-matched controls. Cancer. 2018;124(9):2026–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31270.

Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):974–86. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1997.15.3.974.

Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2002;77(4):371–83. https://doi.org/10.4065/77.4.371.

Cella D, Hahn EA, Dineen K. Meaningful change in cancer-specific quality of life scores: differences between improvement and worsening. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(3):207–21. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015276414526.

Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER, Beck JR, Ross E, Wong YN, et al. Time to surgery and breast cancer survival in the United States. JAMA Oncology. 2016;2(3):330–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4508.

Blinder V, Eberle C, Patil S, Gany FM, Bradley CJ. Women with breast cancer who work for accommodating employers more likely to retain jobs after treatment. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2017;36(2):274–81. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1196.

Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo Z, Bednarek HL. Employment-contingent health insurance, illness, and labor supply of women: evidence from married women with breast cancer. Health Econ. 2007;16(7):719–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1191.

Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2011;77(2):109–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004.

Balak F, Roelen CA, Koopmans PC, Ten Berge EE, Groothoff JW. Return to work after early-stage breast cancer: a cohort study into the effects of treatment and cancer-related symptoms. J Occupational Rehabilitation. 2008;18(3):267–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-008-9146-z.

Blinder VS, Patil S, Thind A, Diamant A, Hudis CA, Basch E, et al. Return to work in low-income Latina and non-Latina white breast cancer survivors: a 3-year longitudinal study. Cancer. 2012;118(6):1664–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26478.

Fantoni SQ, Peugniez C, Duhamel A, Skrzypczak J, Frimat P, Leroyer A. Factors related to return to work by women with breast cancer in northern France. Occupational Rehabilitation. 2010;20(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9215-y.

Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo Z. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):345–53. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.00.4929.

Gudbergsson SB, Fossa SD, Dahl AA. A study of work changes due to cancer in tumor-free primary-treated cancer patients. A NOCWO study Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(10):1163–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0407-3.

Taskila T, Martikainen R, Hietanen P, Lindbohm ML. Comparative study of work ability between cancer survivors and their referents. European J Cancer Oxford England 1990. 2007;43(5):914–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.012.

Bijker R, Duijts SFA, Smith SN, de Wildt-Liesveld R, Anema JR, Regeer BJ. Functional impairments and work-related outcomes in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Occupational Rehabilitation. 2018;28(3):429–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9736-8.

Shim S, Kang D, Bae KR, Lee WY, Nam SJ, Sohn TS, et al. Association between cancer stigma and job loss among cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2021;30(8):1347–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5690.

DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Breast cancer statistics 2019. CA a cancer J Clinicians. 2019;69(6):438–51. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21583.

Rowland JH, Gallicchio L, Mollica M, Saiontz N, Falisi AL, Tesauro G. Survivorship science at the NIH: lessons learned from grants funded in fiscal year 2016. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(2):109–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy208.

Pinto AC, de Azambuja E. Improving quality of life after breast cancer: dealing with symptoms. Maturitas. 2011;70(4):343–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.09.008 (PubMed PMID: 22014722).

Stan D, Loprinzi CL, Ruddy KJ. Breast cancer survivorship issues. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2013;27(4):805–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2013.05.005.

de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, Alfano CM, Padgett L, Kent EE, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):561–70. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-1356.

Forsythe LP, Kent EE, Weaver KE, Buchanan N, Hawkins NA, Rodriguez JL, et al. Receipt of psychosocial care among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(16):1961–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.46.2101.

Kroenke CH, Rosner B, Chen WY, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Holmes MD. Functional impact of breast cancer by age at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1849–56. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.04.173.

Carreira H, Williams R, Muller M, Harewood R, Stanway S, Bhaskaran K. Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(12):1311–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy177.

Payne DK, Sullivan MD, Massie MJ. Women’s psychological reactions to breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23(1 Suppl 2):89–97 (Epub 1996/02/01 PubMed PMID: 8614852).

Avis NE, Levine BJ, Case LD, Naftalis EZ, Van Zee KJ. Trajectories of depressive symptoms following breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1789–95. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-15-0327.

Burg MA, Adorno G, Lopez ED, Loerzel V, Stein K, Wallace C, et al. Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: analysis of open-ended responses to the American Cancer Society Study of Cancer Survivors II. Cancer. 2015;121(4):623–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28951.

Foster C, Wright D, Hill H, Hopkinson J, Roffe L. Psychosocial implications of living 5 years or more following a cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of the research evidence. European J Cancer Care. 2009;18(3):223–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01001.x.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center funded by the University Cancer Research Fund (LCCC2017T204), the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (P50-CA58223, U01-CA179715, T32-CA057726, P30 CA046934), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P30-ES010126).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Marc Emerson, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

No individual person’s data are presented.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Emerson, M.A., Reeve, B.B., Gilkey, M.B. et al. Job loss, return to work, and multidimensional well-being after breast cancer treatment in working-age Black and White women. J Cancer Surviv 17, 805–814 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01252-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01252-6