Abstract

Purpose

Meeting physical activity (PA) guidelines (i.e., ≥ 150 min/week of aerobic PA and/or 2 days/week of resistance training) is beneficial for maintaining cancer survivors’ well-being. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PA participation in cancer survivors and its association on quality of life (QoL) remains unknown. The purpose of this study was to compare PA levels prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and examine the association between changes in PA and QoL in cancer survivors.

Methods

A global sample of cancer survivors participated in a cross-sectional, online survey. Participants self-reported their PA participation before and during the pandemic using the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire and QoL with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scales. Paired t-tests compared PA before and during the pandemic. Analysis of covariance examined differences in QoL between PA categories: non-exercisers, inactive adopters, complete and partial relapsers, single and combined guideline maintainers.

Results

PA participation of cancer survivors (N = 488) significantly decreased during the pandemic (p’s < .001). Cancer survivors were classified as non-exercisers (37.7%), inactive adopters (6.6%), complete (13.1%) and partial (6.1%) relapsers, and single (23.8%) or combined (12.7%) guideline maintainers. Partial relapsers had significantly lower QoL and fatigue than inactive adopters, and combined guideline maintainers (p’s < .05) that were clinically meaningful.

Conclusion

PA decreased during the pandemic which has negative implications for QoL and fatigue in cancer survivors.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

PA is critical for maintaining QoL during the pandemic; therefore, behavioral strategies are needed to help cancer survivors adopt and maintain PA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) a global pandemic (COVID-19) [1]. In February 2021, nearly 1 year since the start of the pandemic, 223 countries have been affected with 108,822,960 confirmed cases and 2,403,641 deaths from COVID-19 [2]. The landscape of cancer care has undergone substantial changes including delays in screening, detection, and non-urgent appointments, changes to treatment delivery, and a widespread utilization of telemedicine [3–6]. This shift in care and disruptions to typical support options (e.g., social workers, financial advising, support from others) [7, 8] is likely to have negative implications on the already compromised physical and mental well-being of cancer survivors during the pandemic [9–14]. Cancer survivors, here referring to any individual who has previously received a cancer diagnosis [15], have reported worry surrounding health and safety, heightened symptoms of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and loneliness or isolation, and poorer global and domain-specific (i.e., social, emotional, role, and cognitive functioning) quality of life (QoL) since the COVID-19 pandemic [9–12, 16].

Since the start of the pandemic, there has been a call to action for the promotion of physical activity (PA) for individuals diagnosed with cancer [17, 18]. Substantial research conducted prior to the pandemic indicates that PA is beneficial for maintaining the health and well-being, reducing anxiety and depression, and improving physical functioning, cancer-related fatigue, and QoL of cancer survivors [19–21]. PA can also reduce the risk of common comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) that further increase susceptibility for severe COVID-19 outcomes and has a potentially immunoprotective effect [22]. Together, this indicates that the uptake and maintenance of PA during the pandemic is critical [17, 18, 22]. It is recommended that cancer survivors engage in a minimum of 150 min/week of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic PA (MVPA) and at least 2 days of resistance training for optimal health benefits, or 30 min of MVPA and/or resistance training, three times per week for cancer-specific benefits [23]. Uptake of these guidelines is low with 46–63% of cancer survivors meeting neither aerobic nor resistance training guidelines and few meeting aerobic only (16–22%), resistance only (7–10%), or combined guidelines (10–20%) [24–26]. Physical distancing measures to help minimize spread of COVID-19 may impose additional and novel barriers to engaging in PA for cancer survivors (e.g., closure of fitness facilities), leading to further reductions in PA participation [17, 18, 27]. Worldwide, general adult populations have reported a substantial reduction in PA [28–32], with between 18 and 34% relapsing to inactivity [30, 32, 33]. Furthermore, these reductions in PA have been associated with poorer mental health outcomes such as increased stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms [32, 34].

There is considerable evidence prior to the pandemic indicating that regular aerobic and resistance training performed both independently and concurrently can lead to more favorable QoL in cancer survivors [20, 35, 36]. It is uncertain whether these associations between PA and QoL hold true amidst the novel threats to cancer survivors’ well-being presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, understanding the impact of the pandemic on the PA behaviors and QoL of cancer survivors is an essential first step needed to inform effective strategies for improving PA and subsequent health outcomes [38]. To our knowledge, only one study to date has examined PA participation of cancer survivors during the pandemic [27]. In a cross-sectional survey of cancer survivors who previously participated in an exercise program designed for cancer survivors (n = 61), 67.2% of participants self-reported a decrease in PA [27]. Though this study suggests COVID-19 has negative implications for cancer survivors, the relationship between PA changes and QoL during the pandemic remains unexplored. Work in larger, population-based samples is needed to substantiate these findings and determine the relationship between changes in PA and QoL during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to examine changes in PA participation of cancer survivors since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondary objectives included examining the association between QoL of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic and change in PA participation across various categories: non-exercisers, inactive adopters, complete relapsers, partial relapsers, and single and combined guideline maintainers. Based on research in healthy populations during the COVID-19 pandemic [31, 32], it is hypothesized that cancer survivors adopting or maintaining PA will have higher QoL compared to relapsers and those remaining inactive.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional, self-administered online survey was conducted between July and November 2020. Informed consent was provided prior to partaking in the study. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board.

Study participants

Eligibility for the study included the following: (a) ≥ 18 years of age, (b) diagnosed with any cancer, and (c) able to complete the survey in English. There were no geographical constraints on who could participate in the study. Eligibility was self-reported after providing informed consent.

Cancer survivors received direct access to the survey on REDCap through a publicly available link on online recruitment materials or through Prolific. The survey took an estimated 45 min to complete. Cancer survivors were recruited using an existing database of survivors previously consenting to being contacted for future research, community cancer organizations, social media, and word of mouth. In addition, the survey was posted on Prolific (www.prolific.co), an international online survey distribution service. Participants recruited through community organizations had the option to enter into a draw to win 1 of 6 $25 CAD Amazon gift cards, and participants using Prolific were compensated with $6.50 CAD via PayPal for their participation.

Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Commonly reported demographic (e.g., gender, age, ethnicity) and clinical (e.g., treatment type, current cancer status) characteristics were self-reported [39–41].

COVID-19 prevention measures

Researcher-generated questions assessed personal and government-mandated COVID-19 infection control measures. Cancer survivors self-reported the country that they were residing in at the time of study participation. For government-mandated prevention measures, the following question was asked “What measures are currently enacted in your country/region in order to reduce the spread of COVID-19?” Response options included “complete lockdown,” “mandatory shelter-in-place,” “suggested shelter-in-place,” “social distancing,” “other,” or “none.” To assess personal measures, participants were asked “What measures have you personally taken to ensure personal health and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic, regardless of regional mandates?” Response options assessed isolation for various reasons including suspected or diagnosed COVID-19 case, experiencing symptoms, recent travel, or perceived vulnerability, social/physical distancing, and relocation from home.

Physical activity

PA participation was assessed using a modified version of the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLETQ) [42] which has been used extensively in cancer populations [e.g., 40, 41, 43, 44]. Participants were asked to recall their average weekly leisure time PA prior to and since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in their country/region. Using an open response format, participants reported the frequency (i.e., sessions per week) and the average duration (i.e., minutes/session) of time spent performing light, moderate, and vigorous aerobic activity and resistance training for a typical week during these timeframes. The GLETQ has reliability coefficients of 0.83 and 0.85 [42].

Consistent with the current aerobic guidelines (i.e., ≥ 150 min of moderate PA or 75 min of vigorous PA) [23, 45], MVPA was calculated by summing the total weekly moderate PA and two times the weekly vigorous PA. Performing resistance training at least two times per week was considered meeting resistance training guidelines. Participants were classified into meeting neither guidelines, aerobic only, resistance training only, and combined guidelines for both before and during the pandemic. Change in MVPA participation was further categorized into six PA change classifications: non-exercisers (i.e., not meeting guidelines), inactive adopters (i.e., meeting any guideline during COVID-19, but not prior to), complete relapsers (i.e., meeting any guideline prior to, but not during COVID-19), partial relapsers (i.e., meeting combined guidelines prior to, but only a single guideline during the pandemic), single guideline maintainers (i.e., meeting a single guideline prior to and during COVID-19), and combined guideline maintainers (i.e., meeting any guideline prior to, and combined guidelines after).

Quality of life

QoL was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scales [46, 47]. The FACT-General is a 27-item questionnaire comprised of four subscales, physical well-being (PWB), social well-being (SWB), emotional well-being (EWB), and functional well-being (FWB) [46, 47]. The FACT-Fatigue includes the FACT-General with an additional 13-item fatigue subscale. PWB, FWB, and fatigue subscales are summed to form the Trial Outcome Index-Fatigue (TOI-Fatigue) scale. Higher FACT scale scores indicate better QoL. Psychometric properties including coefficients of reliability and validity were high and the scale is responsive to clinical change. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) for the FACT-General and FACT-Fatigue scale was 0.92 and 0.95, respectively. Test–retest correlation coefficients was 0.92 for FACT-General and 0.87 for the FACT-Fatigue scale [46, 47].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in R environment for statistical computing (Version 4.1.0). To minimize bias from participants who may be carelessly responding to survey questions, several post hoc methods within the Careless R package [48] were used to determine responses at a high risk of careless responding. These methods included the longstring index (i.e., longest string of the same response), Mahalanobis distance (i.e., multivariate outlier detection), and psychometric synonyms (i.e., within-person correlations between highly positively correlated scale items [critical value = 0.55]) [49, 50]. Any responses with a Mahalanobis distance z-score of > 3.0, a negative psychometric synonyms index, and a longstring index of > 15 and failed reverse-worded items on the FACT-General and FACT-Fatigue scales were considered high risk of careless responding and removed from the analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample and COVID-19 prevention measures. Paired-sample t-tests were used to compare PA participation (i.e., minutes/week) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pearson’s chi-square tests were conducted to compare prevalence of meeting modality-specific PA guidelines from pre-pandemic to during the pandemic.

Separate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) for the FACT-General, FACT-Fatigue, and TOI-Fatigue were conducted to examine the difference in QoL across PA change categories. All models were adjusted for the following covariates (determined a priori): age, gender, body mass index (BMI), cancer type, cancer spread, current cancer status, number of months since diagnosis, and months since last treatment. Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons were conducted on all models reporting statistically significant differences in QoL scores across the PA change categories. Results were interpreted in both their statistical and clinical significance. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Minimally important differences (MIDs) were used to determine if differences in QoL between PA groups were clinically meaningful. MIDs for the FACT-General, FACT-Fatigue, and TOI-Fatigue are 3, 7, and 5 points, respectively [51].

Results

Sample characteristics

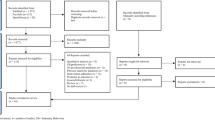

Participant flow through the study is presented in Fig. 1. Of the 592 participants’ responses, 12 were excluded because they indicated they were not diagnosed with cancer, did not provide any cancer-related information, or did not complete the study in English as per the study’s inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 580 survey responses, 516 provided complete PA and QoL responses (i.e., completed ≥ 50% items for each FACT subscale and provided GLETQ responses for both prior to and during the pandemic). After removal of careless responders (n = 28), 488 survey responses remained and were included in the final analysis.

Demographic, medical, and behavioral characteristics of the participants are displayed in Table 1. Cancer survivors were predominantly White (90.0%) and female (69.7%) with a mean age of 48.8 ± 15.6 years. Cancer survivors were primarily diagnosed with localized breast (29.5%), hematologic (11.9%) or gynecologic (11.5%) cancer, and were a mean of 58.1 ± 77.3 months from their last treatment. Participants resided predominantly in the UK (38.1%), the USA (21.9%), and Canada (21.5%). Most cancer survivors indicated government-mandated physical distancing (94.3%) and/or a suggested stay-at-home/shelter-in-place (46.5%).

Change in physical activity participation

Table 2 presents the comparisons of PA before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, cancer survivors were spending on average 207.0 ± 237.9 min/week performing MVPA and only 155.5 ± 195.1 min/week during the COVID-19 pandemic. The percentage of cancer survivors reporting not meeting any PA guidelines significantly increased during the pandemic from 44.3 to 50.8% (χ2(1) = 180.66, p < 0.001). Cancer survivors were engaging in significantly less MVPA during the pandemic when compared to PA prior to the start (Mdiff = − 51.53 min/week; 95% CI = 35.28–67.78; t(487) = 6.23, p < 0.001, d = 0.23). Cancer survivors were primarily classified as non-exercisers (37.7%), single guideline maintainers (23.8%), complete relapsers (13.1%), and combined guideline maintainers (12.7%). Few cancer survivors were classified as inactive adopters (6.6%) or partial relapsers (6.1%).

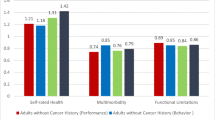

Associations between physical activity and quality of life

Differences in QoL across PA change classifications are presented in Table 3. In the adjusted models, there was a significant difference in FACT-Fatigue (F(5,454) = 2.53; p = 0.03) and TOI-Fatigue (F(5,454) = 3.78; p < 0.01) scores across the PA change classifications. Post hoc comparisons (Table 4) revealed that compared to inactive adopters, partial relapsers had significantly lower QoL and higher fatigue on the FACT-Fatigue (− 21.55; 95% CI = − 40.56 to − 2.54; p = 0.02) and TOI-Fatigue (− 17.19; 95% CI = − 31.66 to − 2.71; p < 0.01). Combined guideline maintainers had significantly lower fatigue and higher QoL on the TOI-Fatigue (13.84 points; 95% CI = 1.15–26.52; p = 0.02) than partial relapsers. All between-group differences in QoL and fatigue were clinically meaningful. There were no significant differences in scores on the FACT-General (F(5,454) = 1.91; p = 0.09) across PA change classifications.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the PA participation of cancer survivors. PA participation significantly decreased (i.e., − 51.5 min/week of MVPA and − 6.5 min/week of resistance training) since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak. While most cancer survivors maintained their pre-pandemic MVPA levels, 19.3% of cancer survivors relapsed in participation and only 6.6% of inactive cancer survivors adopted new PA behaviors, mirroring results seen in general adult populations indicating a decline in PA during the pandemic [28–30]. In a cross-sectional survey, Rhodes and colleagues [30] compared PA behavior of Canadian adults (N = 1055) prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic with results showing a substantial decrease (− 46.7 min/week) in MVPA participation. Furthermore, in studies using smartphone and wearable technologies, substantial decreases in daily step counts have also been documented in non-clinical adult populations [29].

These results are unsurprising for several reasons. First, stress, anxiety, mental health, and PA during the pandemic have all been positively associated with one another [32, 34, 52]. The mental well-being of cancer survivors may be particularly compromised during the COVID-19 pandemic because of factors such as increased vulnerability, inaccessibility of support and coping resources, and uncertainty surrounding health [9–12, 16, 53]. As such, it is possible that this enhanced distress may indirectly impact PA behaviors as cancer survivors experiencing greater mental distress may be less likely to perform PA [31, 52, 53]. Secondly, PA is largely influenced by social and environmental contexts; therefore, COVID-19 prevention measures (i.e., physical distancing and stay-at-home orders) can lead to reduced participation [54]. Changes to the physical and social environment surrounding PA was dramatically changed, as fitness facilities were unavailable or avoided by cancer survivors due to a potential increased risk of COVID-19 transmission [27, 52]. Home-based PA promotion strategies for cancer survivors that reflect this new landscape surrounding PA environments are needed [17, 27].

Our results suggest clinically meaningful differences in QoL scores across PA change classifications. In general, cancer survivors performing PA during the pandemic (i.e., inactive adopters, single and combined guideline maintainers) had higher QoL and lower fatigue than those who are inactive (i.e., non-exercisers, complete and partial relapsers), though only differences between partial relapsers and inactive adopters, and combined guideline maintainers were significant. There are no studies conducted during the pandemic in which to compare our results to; however, these results align with pre-pandemic research indicating that meeting any PA guideline is associated with better QoL [36, 40, 55]. Additionally, much like pre-pandemic research [36, 40, 55], differences in TOI-Fatigue scores across PA change categories suggest that the associations between QoL and PA during the pandemic may be driven primarily by QoL domains related to physical well-being (e.g., fatigue, physical function) compared to social and emotional well-being. Though the association between PA and social and emotional well-being may not be as strong, the potential protective effects of PA on these aspects of well-being should not be overlooked. The FACT subscales are widely used in understanding cancer-specific QoL, but they may not be sensitive to the social and emotional challenges presented by COVID-19. PA shows promise in improving the well-being in general adult populations given that meeting MVPA guidelines during the pandemic is associated with more positive mental health, decreased depression, loneliness, and stress in general adult populations [32]; yet, this remains to be examined in cancer populations. Further work using a broader scope to examine mental well-being is needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of cancer survivors’ QoL and mental health during the pandemic.

Inactive adopters and combined guideline maintainers had significantly better QoL than those who relapsed, suggesting that PA participation during the pandemic is associated with QoL independently from pre-pandemic PA levels. Studies conducted prior to the pandemic show contradictory findings in terms of whether meeting both PA guidelines is superior to meeting only a single guideline [36, 56, 57]. Our results suggest that there is no difference in QoL for those meeting single or combined guidelines. Cancer survivors should therefore strive to perform PA of any modality during the pandemic. Interestingly, despite meeting combined guidelines prior to the pandemic, partial relapsers had the lowest QoL which was clinically meaningful. This suggests that a reduction in PA of any capacity during the pandemic may have detrimental effects on QoL. Caution is needed when interpreting these results as the causal pathway of these relationships cannot be determined in the current analysis. It may also be possible that cancer survivors experiencing poorer QoL during the COVID-19 pandemic may be more susceptible to a relapse in PA. Regardless of directionality, these results are consistent with the relationship between PA and QoL in research conducted prior to the pandemic [20, 35–37]. Therefore, PA programming for cancer survivors during and beyond the pandemic should include a behavioral component for PA maintenance [52, 58].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to suggest that reductions in PA during the pandemic are associated with poorer QoL for cancer survivors. Furthermore, the survey was widely disseminated to a global sample to examine PA and QoL of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study is also subject to limitations. Firstly, although self-report measures provide an easy, accessible, and practical avenue for measuring PA participation in a population-based sample, self-report measures are subject to recall bias and overreporting of MVPA [59]. Given the retrospective nature of PA prior to the pandemic measured at least 4 months following the start of data collection, the estimates of pre-pandemic PA behaviors may also be subject to recall bias. Additionally, directionality of the relationship between change in PA and QoL cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional study design. Participants were primarily White women diagnosed with breast cancer and may not be representative of the broader cancer population. Though this work provides preliminary insight into the PA behaviors and QoL of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic, it may only represent a subset of this population. Cancer survivors of different racial and cultural backgrounds diagnosed with different cancer types and individuals who may not have time to complete a survey were not reached; thus, it is possible that PA and its associations with QoL may present differently in a population not captured through this survey. Purposeful recruitment efforts aimed at reaching underserved populations are needed to increase inclusivity in participation and generalizability of findings to the larger population.

Conclusion

With 18 million people living with cancer globally [60, 61] and facing disruptions to medical and supportive care, it is imperative to investigate strategies that can simultaneously target physical and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. The effects of PA on health and well-being of cancer survivors have been well-documented [62], and PA should be considered essential for addressing many of the physical and mental consequences imposed by COVID-19 infection control measures [17, 18].

To optimize benefits from PA, behavioral strategies and interventions are needed to assist cancer survivors in adopting PA and also preventing current exercisers from relapsing [58]. Strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic include educating survivors on how to remain active yet physically distant from others, self-regulatory strategies to prevent momentary lapses and overcome barriers, and utilizing live, virtual programming to facilitate personal connections, provide rapid feedback and personalized instruction [17, 52, 58, 63]. This requires a thorough understanding of the motivational and environmental determinants of PA in cancer populations during the pandemic. PA promotion strategies and interventions for this population should consider utilizing social ecological approaches, targeting all levels of influence including individual, interpersonal, and environmental factors. Overall, meeting any of the PA guidelines can have a positive effect on QoL and fatigue of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 response [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline#. Accessed 2021 Feb 16.

World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Feb 16]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 2021 Feb 16.

Gill S, Hao D, Hirte H, Campbell A, Colwell B. Impact of COVID-19 on Canadian medical oncologists and cancer care: Canadian Association of Medical Oncologists survey report. Curr Oncol. 2020;27:71–4.

Chan A, Ashbury F, Fitch MI, Koczwara B, Chan RJ. Cancer survivorship care during COVID-19—perspectives and recommendations from the MASCC survivorship study group. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3485–8.

Jones D, Neal RD, Duffy SRG, Scott SE, Whitaker KL, Brain K. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the symptomatic diagnosis of cancer: the view from primary care. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:748–50.

Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, Rogado A, Alsharm AA, Razis ED, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care: a global collaborative study. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1428–38.

Clark-Snow RA, Rittenberg C. Oncology nursing supportive care during the COVID-19 pandemic: reality and challenges. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:2259–62.

Frey MK, Chapman-Davis E, Glynn SM, Lin J, Ellis AE, Tomita S, et al. Adapting and avoiding coping strategies for women with ovarian cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160:492–8.

Younger E, Smrke A, Lidington E, Farag S, Ingley K, Chopra N, et al. Health-related quality of life and experiences of sarcoma patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancers. 2020;12:2288.

Helm EE, Kempski KA, Galantino MLA. Effect of disrupted rehabilitation services on distress and quality of life in breast cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rehabil Oncol. 2020;38:153–8.

Frey MK, Ellis AE, Zeligs K, Chapman-Davis E, Thomas C, Christos PJ, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on the quality of life for women with ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(725):e1-9.

Lou E, Teoh D, Brown K, Blaes A, Holtan SG, Jewett P, et al. Perspectives of cancer patients and their health during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE. 2020;15:e0241741.

Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:343–51.

Naughton MJ, Weaver KE. Physical and mental health among cancer survivors: considerations for long-term care and quality of life. N C Med J. 2014;75:283–6.

National Cancer Institute. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms [Internet]. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. [cited 2021 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/survivorship. Accessed 2021 Nov 1

Bargon CA, Batenburg MCT, van Stam LE, Mink van der Molen DR, van Dam IE, van der Leij F, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient-reported outcomes of breast cancer patients and survivors. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5:1–11.

Avancini A, Trestini I, Tregnago D, Wiskemann J, Lanza M, Milella M, et al. Physical activity for oncological patients in COVID-19 era: no time to relax. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4:pkaa071.

Rezende LFM, Lee DH, Ferrari G, Eluf-Neto J, Giovannucci EL. Physical activity for cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action. Cancer Causes Control. 2021;32:1–3.

Buffart LM, Kalter J, Sweegers MG, Courneya KS, Newton RU, Aaronson NK, et al. Effects and moderators of exercise on quality of life and physical function in patients with cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 34 RCTs. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:91–104.

Gerritsen JKW, Vincent AJPE. Exercise improves quality of life in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:796–803.

Scott JM, Zabor EC, Schwitzer E, Koelwyn GJ, Adams SC, Nilsen TS, et al. Efficacy of exercise therapy on cardiorespiratory fitness in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2297–305.

Woods JA, Hutchinson NT, Powers SK, Roberts WO, Gomez-Cabrera MC, Radak Z, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and physical activity. Sports Med Health Sci. 2020;2:55–64.

Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, May AM, Schwartz AL, Courneya KS, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2375–90.

Tabaczynski A, Strom DA, Wong JN, McAuley E, Larsen K, Faulkner GE, et al. Demographic, medical, social-cognitive, and environmental correlates of meeting independent and combined physical activity guidelines in kidney cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:43–54.

Crawford JJ, Holt NL, Vallance JK, Courneya KS. A new paradigm for examining the correlates of aerobic, strength, and combined exercise: an application to gynecologic cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3533–41.

Vallerand JR, Rhodes RE, Walker GJ, Courneya KS. Correlates of meeting the combined and independent aerobic and strength exercise guidelines in hematologic cancer survivors. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:1–10.

Faro JM, Mattocks KM, Nagawa CS, Lemon SC, Wang B, Cutrona SL, et al. Physical activity, mental health and technology preferences to support cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. JMIR Cancer. 2021;7:e25317.

Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients. 2020;12:1583.

Tison GH, Avram R, Kuhar P, Abreau S, Marcus GM, Pletcher MJ, et al. Worldwide effect of COVID-19 on physical activity: a descriptive study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:767–70.

Rhodes RE, Liu S, Lithopoulos A, Garcia-Barrera MA, Zhang CQ. Correlates of perceived physical activity transitions during the COVID-19 pandemic among Canadian adults. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2020;12:1157–82.

Lesser IA, Nienhuis CP. The impact of COVID-19 on physical activity behavior and well-being of Canadians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3899.

Meyer J, McDowell C, Lansing J, Brower C, Smith L, Tully M, et al. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior in response to COVID-19 and their associations with mental health in 3052 UA adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:6469.

Schuch FB, Bulzing RA, Meyer J, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Stubbs B, et al. Associations of moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary behavior with depressive and anxiety symptoms in self-isolating people during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey in Brazil. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113339.

Jacob L, Tully MA, Barnett Y, Lopez-Sanchez GF, Butler L, Schuch F, et al. The relationship between physical activity and mental health in a sample of the UK public: a cross-sectional study during the implementation of COVID-19 social distancing measures. Ment Health Phys Act. 2020;19:100345.

Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Snyder C, Geigle P, Gotay C. Are Exercise programs effective for improving health-related quality of life among cancer survivors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;41:e326–42.

Trinh L, Strom DA, Wong JN, Courneya KS. Modality-specific exercise guidelines and quality of life in kidney cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2419–26.

Buffart LM, Newton RU, Chinapaw MJ, Taaffe DR, Spry NA, Denham JW, et al. The effect, moderators, and mediators of resistance and aerobic exercise on health-related quality of life in older long-term survivors of prostate cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:2821–30.

Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;20:1–14.

Strollo SE, Fallon EA, Gapstur SM, Smith TG. Cancer-related problems, sleep quality, and sleep disturbance among long-term cancer survivors at 9-years post diagnosis. Sleep Med. 2020;65:177–85.

Trinh L, Plotnikoff RC, Rhodes RE, North S, Courneya KS. Associations between physical activity and quality of life in a population-based sample of kidney cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20:859–68.

Forbes CC, Blanchard CM, Mummery WK, Courneya KS. A comparison of physical activity correlates across breast, prostate and colorectal cancer survivors in Nova Scotia, Canada. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:891–903.

Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:141–6.

Eng L, Pringle D, Su J, Shen X, Mahler M, Niu C, et al. Patterns, perceptions, and perceived barriers to physical activity in adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:3755–63.

Phillips SM, McAuley E. Associations between self-reported post-diagnosis physical activity changes, body weight changes, and psychosocial well-being in breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:159–67.

Segal R, Zwaal C, Green E, Tomasone JR, Loblaw A, Petrella T. Exercise for people with cancer: a clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2017;24:40–6.

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9.

Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) Measurement System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:63–74.

Yentes R, Wilhelm F. Careless: Procedures for Computing Indices of Careless Responding. R packages version 1.2.1. 2021. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=careless. Accessed 9 Aug 2021.

Curran PG. Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2016;66:4–19.

Meade AW, Craig SB. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol Methods. 2012;17:437–55.

Yost KJ, Eton DT. Combining distribution- and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally important differences: the FACIT experience. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:172–91.

Newton RU, Hart NH, Clay T. Keeping patients with cancer exercising in the age of COVID-19. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:656–65.

Nekhlyudov L, Duijts S, Hudson SV, Jones JM, Keogh J, Love B, et al. Addressing the needs of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14:601–6.

Kwasnicka D, Dombrowski SU, White M, Sniehotta F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: a systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10:277–96.

Vallance JK, Boyle T, Courneya KS, Lynch BM. Associations of objectively assessed physical activity and sedentary time with health-related quality of life among colon cancer survivors. Cancer. 2014;120:2919–26.

Courneya KS, McKenzie DC, Mackey JR, Gelmon K, Friedenreich CM, Yasui Y, et al. Effects of exercise dose and type during breast cancer chemotherapy: multicenter randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1821–32.

Taaffe DR, Newton RU, Spry N, Joseph D, Chambers SK, Gardiner RA, et al. Effects of different exercise modalities on fatigue in prostate cancer patients undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: a year-long randomised controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2017;72:293–9.

de Oliveira NL, Elsangedy HM, Tavares VDDO, Teixeira CVLS, Behm DG, da Silva-Grigoletto ME. #TrainingInHome - training at home during the COVID-19 (SAR-COV2) pandemic: physical exercise and behavior-based approach. Revista Brasileira de Fisiologia do Exercício. 2020;19:9–19.

Welch WA, Lloyd GR, Awick EA, Siddique J, McAuley E, Phillips SM. Measurement of physical activity and sedentary behavior in breast cancer survivors. J Community Support Oncol. 2018;15:e21-29.

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68:394–424.

World Cancer Reserach Fund/ American Insitute of Cancer Research. Worldwide Cancer Data [Internet]. 2018. Accessed From: https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer/worldwide-cancer-data/. Accessed 3 Mar 2021.

Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, Hayes SC, Silver JK, Campbell KL, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cancer prevention and control. Med Sci Sports Exerc Sci. 2019;51:2391–402.

Hammami A, Harrabi B, Mohr M, Krustrup P. Physical activity and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): specific recommendations for home-based physical training. Manag Sport Leisure. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1757494

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Toronto COVID-19 Student Engagement Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AT, AW, DB, and LT contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AT contributed to the interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. AW, DB, and LT contributed to the interpretation of the data and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the University of Toronto’s Research Ethic’s Board.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tabaczynski, A., Bastas, D., Whitehorn, A. et al. Changes in physical activity and associations with quality of life among a global sample of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Cancer Surviv 17, 1191–1201 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01156-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01156-x