Abstract

Seasonal patterns of wood formation (xylogenesis) remain understudied in mixed pine–oak forests despite their contribution to tree coexistence through temporal niche complementarity. Xylogenesis was assessed in three pine species (Pinus cembroides, Pinus leiophylla, Pinus engelmannii) and one oak (Quercus grisea) coexisting in a semi-arid Mexican forest. The main xylogenesis phases (production of cambium cells, radial enlargement, cell-wall thickening and maturation) were related to climate data considering 5–15-day temporal windows. In pines, cambium activity maximized from mid-March to April as temperature and evaporation increased, whereas cell radial enlargement peaked from April to May and was constrained by high evaporation and low precipitation. Cell-wall thickening peaked from June to July and in August–September as maximum temperature and vapour pressure deficit (VPD) increased. Maturation of earlywood and latewood tracheids occurred in May–June and June–July, enhanced by high minimum temperatures and VPD in P. engelmannii and P. leiophylla. In oak, cambial onset started in March, constrained by high minimum temperatures, and vessel radial enlargement and radial increment maximized in April as temperatures and evaporation increased, whereas earlywood vessels matured from May to June as VPD increased. Overall, 15-day wet conditions enhanced cell radial enlargement in P. leiophylla and P. engelmannii, whereas early-summer high 15-day temperature and VPD drove cell-wall thickening in P. cembroides. Warm night conditions and high evaporation rates during spring and summer enhanced growth. An earlier growth peak in oak and a higher responsiveness to spring–summer water demand in pines contributed to their coexistence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In extratropical biomes across the northern hemisphere, Pinus and Quercus species are major forest components and provide multiple ecological and economic services (e.g., timber, fuelwood, resins, fodder, food sources, habitat for wildlife). In Mexico and the continental United States, these species coexist in many seasonal drought-prone areas (Cavender-Bares 2016). These mixed pine–oak forests are still understudied in Mexico (but see Martin et al. 2021), where 39% and 41% of the worldwide pine and oak species, respectively, have been described as endemic (Farjon and Styles 1997; Gernandt and Pérez de la Rosa 2014; Hipp et al. 2018). Therefore, a better understanding is needed of the mechanisms driving the coexistence of pine and oak species in seasonally dry, diverse regions across Mesoamerica such as northern Mexico.

Pine–oak forests are some of the most vulnerable ecosystems to the impacts of climate warming (Galicia et al. 2015), which is predicted to increase the severity of seasonal droughts in Mexico through increased evapotranspiration rates (Seager et al. 2009). Sympatric pine and oak species present physiological adaptations to seasonal water shortages contributing to their coexistence by using water in different periods or by taking it from different soil depths (Aguilar-Romero et al. 2017; Fallon and Cavender-Bares 2018). For example, in Mediterranean sites, oaks tend to exploit deeper soil water sources than coexisting pines during summer droughts (Del Castillo et al. 2016). In the case of oaks, niche partitioning among closely related species has been linked to trade-offs between drought avoidance or tolerance (desiccation recovery) and growth rates (Fallon and Cavender-Bares 2018). For instance, oak species from arid areas had more deciduousness and higher water-use efficiency than oak species from humid sites (Aguilar-Romero et al. 2017). Other studies also found that oak species with higher drought tolerance inhabited low elevation, xeric sites (Martin et al. 2021). Overall, drought severity affects the distribution and coexistence of pine and oak species in Mexico.

Fluctuating harsh conditions contribute to explaining coexistence in diverse forests (Chesson and Huntly 1997). Drought seasonality and severity may drive resource availability through time leading to different radial growth and xylem phenology (xylogenesis) patterns as observed in diverse dry tropical forests (García-Cervigón et al. 2019). Variable intra-annual growth responses to drought among co-existing tree species can contribute to diversity maintenance through temporal niche complementary (Schwinning and Kelly 2013). To determine if differences in growth sensitivity to drought affect temporal resource heterogeneity and coexistence of pine and oak species, detailed analyses on xylogenesis as related to climate are needed.

Semi-arid and arid forests are strategic sites for developing xylogenesis studies because seasonal water shortages exert a key control over tree radial growth and carbon fixation (Pasho et al. 2012; Martín-Benito et al. 2013; Ziaco et al. 2018; Zeng et al. 2020; Morino et al. 2021). Shifts in drought severity differentially impact trees, related to their ability to adjust to changes in soil moisture availability (Vieira et al. 2020). Therefore, northern Mexican pine–oak forests and nearby regions subjected to seasonal water changes driven by summer monsoons, are ideal settings to disentangle the impacts of intra- and inter-annual climate variability on xylogenesis (Szejner et al. 2020; Pompa-García et al. 2021a, 2021b). In similar seasonally dry forests subjected to high evapotranspiration rates, low and variable precipitation, and cold winter temperatures, xylogenesis was constrained by early growing season water availability (Camarero et al. 2010; Ren et al. 2019).

In this study, xylogenesis data was analyzed over a complete growing season for three pine species (Pinus engelmannii Carr., Pinus cembroides Zucc., Pinus leiophylla subsp. chihuahuana (Engelm.) E. Murray) coexisting with an oak species (Quercus grisea Liebm.) in a Mexican forest under semi-arid conditions. The goals were: (1) to determine the seasonal dynamics of xylogenesis; (2) to assess the climatic drivers of xylogenesis by relating wood-formation phases with climate data; and, (3) to discern if different xylogenesis responses to seasonal climate, particularly to drought, explain the coexistence of tree species. It was expected that species showing lower climatic constraints in their major growth phase, radial cell expansion (cf. Vaganov et al. 2006), under water demand would be those with the highest drought tolerance. This would be the case of P. leiophylla which inhabits semi-arid sites, whereas less tolerant species such as P. engelmannii would have the highest correlations between wood formation and atmospheric water demand. Strong responses of vessel radial enlargement to water demand were also expected for Q. grisea, given the strong stomatal regulation of water loss during drought that oaks from semi-arid sites tend to show (Fallon and Cavender-Bares 2018).

Material and methods

Study site

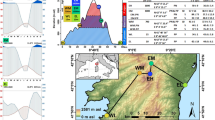

The study area was a 1.6-ha stand located near “Río Chico” village (23.92º N, 104.87º E, 2131 m a.s.l.) in Durango, northern Mexico (Fig. 1). Five mature, healthy trees per species were sampled. We considered three pine species (P. engelmannii, P. cembroides, P. leiophylla subsp. Chihuahuana—hereafter P. leiophylla) and one oak species (Q. grisea). These species are representative of diverse, mixed pine–oak forests dominant across drought-prone areas of the Sierra Madre Occidental in northern Mexico, and provide multiple environmental goods and services to local communities (Farjon and Styles 1997; González-Elizondo et al. 2012). The climate is seasonally dry with monsoonal summer rains. The mean annual temperature is 15.5 ºC and the average annual precipitation is 550 mm. Mean temperature during the study period (March 2019–March 2020) was 18.7 ºC, total precipitation 361 mm and mean monthly evaporation 278 mm (Fig. 2).

Climate data for the study site and during the monitoring period (March 2019–March 2020; DOY, day of the year) averaged (minimum and maximum temperatures, VPD) or summed (evap., evaporation; prec.–evap., difference between precipitation and evaporation) for 5-, 10- and 15-day periods; a temperature, b evaporation (positive values) and differences between precipitation and evaporation (negative values), and c vapour pressure deficit (VPD)

Climate data

Daily climate variables were recorded in the nearby “Río Chico” climatological station located 5 km from the study site: Tmin and Tmax, minimum and maximum temperatures, respectively; precipitation; and evaporation. The differences between precipitation and evaporation (Prec.–Evap.) were calculated as a surrogate of available soil moisture. Vapor pressure deficit (VPD) was calculated from air temperatures and vapor pressure to estimate evaporative water demand, following Grossiord et al. (2020).

The warmest and coldest months during the period were June 2019 (mean maximum temperature of 31.1 ºC) and January 2020 (mean minimum temperature of 3.9 ºC). The months with highest and lowest evaporation values were May 2019 (474 mm) and November 2019 (146 mm). The year 2019 was dry with a total precipitation of 299 mm. Soils on the site are shallow, leading to low productivity and open stands (Fig. 2).

Tree species

With regards to the characteristics of the study species, the Apache pine, P. engelmannii inhabits mountain sites; it regenerates after low-intensity fires and its growth is constrained by warm, dry conditions in winter and spring (Bickford et al. 2011; González-Casares et al. 2016). P. cembroides, the pinyon pine, is native to the mountains of Mexico and southwestern USA where it occupies transitional zones between semi-arid plateaus and montane areas with rocky, poorly developed soils (Farjon and Styles 1997). This species is also sensitive to drought in winter-spring and to low winter temperatures (Carlón Allende et al. 2018; Herrera-Soto et al. 2018). The Chihuahua pine, P. leiophylla, develops well in the study site and it is tolerant to drought and wide thermal ranges, being distributed in semi-arid sites across the southern USA and northern Mexico (Acosta-Hernández et al. 2019). However, this species is considered sensitive to climate warming (Galicia et al. 2015). Lastly, Q. grisea, the grey oak, is distributed from central Mexico to southwestern USA and is codominant in Madrean pine-oak woodlands and in formations with P. cembroides and Juniperus spp. (Little 1950). It may grow as a single stemmed tree to a multi-stemmed shrub form, with evergreen or drought-deciduous leaves, depending on winter precipitation (Aguilar and Boecklen 1992). This species has considerable tolerance to wilting and a low tolerance to cold damage, making it a species suited for surviving prolonged summer drought stress (Fallon and Cavender-Bares 2018).

Xylogenesis: analyses of wood formation

Since obtaining xylogenesis data is highly time-consuming, it was considered that five mature trees per species would be sufficiently representative. Similar approaches have been used in other xylogenesis studies (e.g., Rossi et al. 2006). To assess xylogenesis, wood microcores (2 mm diameter and 15–20 mm length) were taken biweekly (16-day intervals) from March 2019 to March 2020. Selected trees were dominant and healthy. In addition to xylogenesis, the dates of the start of bud burst and leaf unfolding were also assessed.

Trees were sampled with a Trephor® increment puncher, which allowed for extracting microcores at 1–1.5 m height, in an ascending spiral pattern, with each sample taken 5 cm from the previous sampling point (Rossi et al. 2006; Deslauriers et al. 2015). The samples contained the previous 4–5 annual rings and the current annual ring with the cambium and adjacent xylem and phloem. Microcores were fixed in 50% ethanol and preserved. Transversal 15–20 μm sections were obtained using a sliding microtome (Leica SM2010 R, Germany), mounted on glass slides, stained with 0.05% cresyl violet and fixed with Eukitt®. The sections were examined with visible and polarized light within 10–30 min of staining. Images of sections were taken at 40–100 × magnification using a digital camera mounted on a light microscope (Olympus BH2, Germany).

On five radial lines per ring, the number of cambium cells, radially enlarging tracheids, wall-thickening tracheids and mature cells were counted and an average made (Camarero et al. 2010). Images allowed verifying cell counts and distinguishing earlywood (EW) and latewood (LW) tracheids according to their lumen and cell wall thickness, and distinguishing earlywood from latewood tracheids as a function of their lumen diameter and wall thickness (Denne 1989). In the developmental stage, cells show different shapes and stain with different colors (Antonova and Stasova 1993). Cambial cells had similar, small radial diameters and thin walls; radially elongating tracheids showed wider diameters and contained protoplasts enclosed by thin primary walls; wall-thickening tracheids corresponded to the onset of secondary cell wall formation and were characterized by cell wall corner rounding; secondary walls glistened under polarized light and walls turned blue due to lignification; mature cells did not contain cytoplasm and showed completely blue walls.

With the oak, the methods of Frankenstein et al. (2005) and Pérez-de-Lis et al. (2016) were followed. The radial increment was first measured under the microscope. Since Q. grisea forms ring-porous wood, the number of trees showing in each sampling date the following xylogenesis phases were recorded: cambial resumption (when a distinct enlargement of cambium derivatives and cell division were observed), and enlargement and maturation (when both wall thickening and lignification were observed) of earlywood vessels. The dates of phenology and xylogenesis are given as calendar or Julian days.

Statistical analyses

To assess how xylogenesis responded to climate, several time windows of climate data were considered, specifically 5-, 10- and 15-day intervals prior to each sampling date (see Gutierrez et al. 2011). Tmin, Tmax, and VPD were averaged or summed (evaporation; Prec.–Evap.) to be the climate variables for the three-time intervals. Spearman correlation coefficients between the calculated climate variables and the xylogenesis phases were calculated, since most variables did not follow normal distributions. Pine and oak xylogenesis data and their relationships with climate are presented in different figures, since different variables were considered to characterize wood formation in the two groups.

Results

Leaf phenology

Based on field observations, the three pine species started needle sprouting on 8 March. The first P. cembroides needles emerged 22 March, by P. engelmannii 29 March, and on 5 April by P. leiophylla. Oak buds started flushing and formed the first leaves in late March.

Xylogenesis of pine species

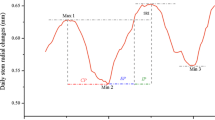

Cambial activity peaked in the pine species in March with a maximum production of radially enlarging tracheids from April to May (Figs. 3 and 4). P. leiophylla showed an earlier and greater peak in radial growth in mid-April, a date when P. cembroides growth also peaked, while P. engelmannii growth peaked in early May. The three pine species showed radially elongating tracheid peaks from August to September, lower in magnitude than in the spring.

Cross-sections showing early xylogenesis phases (radially enlarging cells with thin, blue-stained walls located in the right side of images) of the three pine species (a, P. engelmannii, 5 April; b, P. leiophylla, 5 April; c, P. cembroides, 18 April) and the oak (d, Q. grisea, 3 May). Bars measure 0.5 mm. Stars indicate recently formed cells

With regards to the development of thickening in cell wall tracheids, both P. leiophylla and P. cembroides showed maximum production from early June to mid-July, whereas P. engelmannii tracheid production peaked in mid-June. Secondary peaks were observed in mid-July for P. cembroides and in early August to late September for the three species. The rate of production of mature earlywood tracheids peaked from mid-May for P. leiophylla to mid-June for P. cembroides and P. engelmannii. The rate of production of mature latewood tracheids increased from late June for P. leiophylla and P. cembroides and to late July for P. engelmannii. P. leiophylla and P. engelmannii showed the earliest and latest xylogenesis phases. Xylogenesis phases (cambium dynamics, radial enlargement, cell wall thickening and maturation) showed significant (P < 0.01) and positive relationships among the three pine species, indicating similar wood formation paces.

Xylogenesis of Q. grisea

Cambial reactivation was observed from late March to early April (Fig. 5). Most trees (80–100%) showed the enlargement of earlywood vessels in early April when the maximum radial increment rate 0.014 mm d−1 was observed. The onset of earlywood vessel maturation started in May and was observed in all trees from late June when earlywood vessel enlargement ceased and the first latewood vessels were detected.

Relationships between climate and xylogenesis in pine species

The number of cambial cells was positively related to the 15-day evaporation and 10-day mean maximum temperature, with the highest correlations in P. engelmannii (Fig. 6). The production of radial enlarging tracheids was positively related to the 15-day evaporation data and negatively to the 15-day differences between precipitation and evaporation for P. leiophylla. The thickening of cell walls was positively related to 15-day mean maximum temperature and VPD with the highest correlations in P. cembroides and P. engelmannii. The cumulative number of earlywood cells positively responded to the 5-day mean minimum temperature and VPD in P. engelmannii, but negatively to the 15-day differences between precipitation and evaporation in P. leiophylla. The cumulative number of latewood cells was positively correlated with mean minimum temperature and VPD, showing the maximum correlation for 15-day mean minimum temperature values and P. engelmannii.

Climate-xylogenesis relationships in the three pine species (Pe, Pl and Pc correspond to P. engelmannii, P. leiophylla and P. cembroides, respectively) considering different xylem formation phases (production of cambium cells, radially-enlarging cells, wall-thickening cells, rates of production of mature earlywood –EW– and latewood –LW– tracheids); different color bars correspond to 5, 10 and 15-day averaged or summed climate data; horizontal dashed and dotted lines indicate 0.05 and 0.01 significance levels, respectively

Relationships between climate and xylogenesis in Q. grisea

The production of cambial cells was negatively related to the 10-day mean minimum temperature and 15-day VPD values, whereas the enlargement of earlywood vessels was positively correlated with 5 and 15-day mean maximum temperature and evaporation but negatively with differences between precipitation and evaporation (Fig. 7). The maturation of earlywood vessels was positively related to 10 and 15-day VPD values. Lastly, radial growth rate was not correlated with climate variables.

Climate-xylogenesis relationships in Q. grisea. The different color bars correspond to 5, 10 and 15-day averaged (Tmin and Tmax, minimum and maximum temperatures, respectively; VPD, (vapour pressure deficit) or summed (evaporation; Prec.–Evap., difference between precipitation and evaporation) climate data. For each climate variable different xylem formation phases or variables were considered: Cam, cambial resumption; Enl, enlargement of vessels; Mat, maturation of vessels; and GR, growth rate; horizontal dashed and dotted lines indicate 0.05 and 0.01 significance levels, respectively

Discussion

It was speculated that differential timings of the main xylogenesis phases and diverse responses to climate would explain coexistence among the tree species. The results support these expectations since the oak showed earlier xylogenesis phases than pines and different responses to climate.

Climate drivers of xylogenesis

Species showing lower climatic constraints for radial cell expansion by water demand such as P. leiophylla, corresponded to those most tolerant to drought, whereas species from wetter sites such as P. engelmannii and P. cembroides showed the highest correlations between wood formation and atmospheric water demand. Overall, 15-day wet conditions in spring enhanced cell radial enlargement, particularly in P. leiophylla and P. engelmannii, whereas early summer 15-day temperatures and VPD drove cell wall thickening in summer in P. cembroides. Tracheid maturation occurred from spring to summer, and was enhanced by high minimum temperatures and VPD, mainly for P. engelmannii and P. leiophylla. In Q. grisea, earlywood vessel radial enlargement and radial increment peaked in spring and increased as temperature and evaporation increased, whereas vessel maturation from spring to summer was aligned to the rise in vapor pressure deficit.

Seasonal analyses may be compared with tree-ring studies comparing year-to-year climate and growth variability. Bickford et al. (2011) found that growth was enhanced by winter-spring precipitation and that more severe droughts reduced the growth of P. engelmannii on dry, warm, low-elevation sites. These findings agree with our analyses that xylogenesis in P. engelmannii depends on water availability. González-Casares et al. (2016) reported that P. leiophylla growth was enhanced by high winter precipitation and cold conditions increasing soil moisture. However, in this study, it was observed that cell radial enlargement in this species was tightly related to 15-day high evaporation rates, suggesting that atmospheric water demand drives cambium division and cell expansion whenever soil moisture was not limiting and cell turgor not reduced. These results agree with recent findings showing the relevance of atmospheric water demand as a driver of radial increment rates rather than soil moisture (Zweifel et al. 2021; Etzold et al. 2022). However, there were no correlations of xylogenesis phases with vapor pressure deficits except during cell wall thickening, but were positive with temperature which is tightly related to VPD. This discrepancy may be due to the approximate estimates used for calculating VPD or to the fact that the production of new cells was measured in a drought-prone site, whereas Zweifel et al. (2021) measured radial increment rates using dendrometers in temperate, wet forests.

Differences and similarities in xylogenesis among coexisting pine and oak species

Overall, warmer conditions enhanced cambial activity and xylem development in the three pine species and in oak. This suggests a direct relationship between meristematic activity and warmer conditions as described in cold biomes (Rossi et al. 2008). Such growth response to warm spring conditions could also influence xylem response to atmospheric water demand, as shown by the direct association between cell enlargement and evaporation observed in the four species. The fact that P. leiophylla produced the highest number of radially enlarged tracheids suggests a greater capacity to use carbohydrates during earlywood formation, possibly linked to adequate soil moisture provided by winter-spring precipitation (Pompa-García et al. 2021a).

The thermal and evaporation seasonal regimes influence cell radial enlargement and wall thickening. As the atmospheric water demand keeps rising from spring to summer and soils begin to dry, fast-growing species such as P. leiophylla reduce the production of radially enlarged tracheids. This species showed the latest needle expansion, suggesting the use of recently synthesized carbohydrates for late summer growth (Buttò et al. 2020). This would lead to a bimodal growth pattern (cf. Camarero et al. 2010). Warmer and drier climates lead to the production of tracheids with narrow lumens slowing down radial enlargement (Vaganov et al. 2006). In contrast, P. cembroides and P. engelmannii had a lower rate of wood formation but longer xylogenesis, even though earlier needle formation. Such protracted wood phenological patterns could allow these species to tolerate drought by growing during favorable conditions in autumn.

Cell wall thickening, which is a carbon-demanding process (Cuny et al. 2015), occurred during the warmest season for the three pines and would explain its positive correlation with vapour pressure deficits. A similar result was observed for earlywood vessel maturation in Q. grisea. The P. cembroides cell wall thickening phase peaked during the summer solstice, suggesting links with the photoperiod. Thus, although the impact of day length on xylem formation is variable annually, it should be given more consideration (Zhang et al. 2018). Summer thermal conditions were favorable for photosynthesis for enhancing cell wall thickening. Although Gao et al. (2021) reported that drought limits the rate of production of cell wall thickening tracheids, it was found that a 15-day vapour pressure deficit was directly related to this xylogenesis phase. High transpiration rates linked to elevated vapour pressure deficits may maintain cell turgor and promote the division of cambial cells and tracheid maturation (Vieira et al. 2020). These findings suggest delayed responses of xylem development to climatic conditions, which is consistent with findings from nearby semi-arid sites (Ziaco et al. 2016, 2018).

In P. engelmannii and P. cembroides, the rate of cell wall thickening was stimulated by both elevated mean minimum temperatures and vapour pressure deficits, suggesting that radial growth mainly depended on night conditions as reported by Zweifel et al. (2021). This also supports the observation that the demand for atmospheric water is a major promoter of xylogenesis, which is consistent with studies from seasonally dry sites (Vieira et al. 2020; Morino et al. 2021). A potential association between water demand (VPD), stomatal regulation of water loss and xylogenesis phases (e.g., cell wall thickening), could explain adaptive mechanisms to tolerate drought (see Garcia-Forner et al. 2019).

Growth bimodality in pines: adjusting to seasonal drought

The bimodal growth patterns observed for the three pine species with the post-summer peak of radially enlarging cells for P. leiophylla and P. cembroides, preceded by approximately a month that of P. engelmannii, agrees with those found in nearby, seasonally dry forests subjected to summer monsoons (Morino et al. 2021; Pompa-García et al. 2021a). The higher availability of soil moisture and the decrease in atmospheric demand during monsoon rains reactivates tracheid expansion after the summer drought, resulting in post-summer growth recovery (Morino et al. 2021). This is consistent with previous studies in other seasonally dry forests (Camarero et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2020; Oberhuber et al. 2021). Interestingly, Ziaco et al. (2018) found that the onset of cambial activity after summer drought was associated with increases in humidity prior to the first monsoon rains in the semi-arid southwestern USA, confirming our findings of the major role of atmospheric water demand as a driver of wood growth.

Growth bimodality may be an adaptation to favorable conditions of atmospheric water demand and soil moisture. Such growth adjustments to seasonal drought can contribute to tree species coexistence, and should be considered when carrying out dendroclimatic reconstructions, since earlywood and latewood production captures different climate impacts on radial growth (Griffin et al. 2013; Acosta-Hernández et al. 2017). This was confirmed by our study, with earlywood and latewood maturation peaking in spring and in summer, respectively. There are also implications for changes in carbon distribution and hydraulic functioning. For example, the production of tracheids with wide lumens may accelerate hydraulic recovery, whereas latewood production may depend on recently fixed carbon (Garcia-Forner et al. 2019). Therefore, forecasted changes in hydrological regimes will mainly affect radial enlargement, which is the most sensitive phase to water shortages and influences annual growth (Cuny et al. 2015). In our study site, P. leiophylla had the highest production of mature earlywood cells, suggesting that growth was adjusted to climate conditions and a low response to spring thermal conditions and atmospheric water demand. In contrast, the production of earlywood and latewood tracheids in P. engelmannii was dependent on changes in mean minimum temperatures.

Oak growth patterns and responses to climate

Although several studies have examined ring- and diffuse-porous Quercus spp. under seasonally dry conditions in Mediterranean forests (Corcuera et al. 2004a, 2004b; Gutierrez et al. 2011; González-González et al. 2014; Pérez-de-Lis et al. 2016), this study reports for the first time the responses by Q. grisea in a semi-arid, monsoonal region. Wet conditions in spring induce the cambial activation of this species, whereas high evaporation triggered radial enlargement of earlywood vessels during spring and summer. The maturation of these cells peaked in summer when vapour pressure deficit and photoperiod increased (Fonti et al. 2010). This xylogenesis pattern contributes to its high drought tolerance and allows its coexistence with pines (Cavender-Bares 2016). It is suggested that the oak could outcompete the pine species by growing during dry periods with elevated vapour pressure deficits through the uptake of deep soil water (Del Castillo et al. 2016). However, the effects of extreme hot and successive droughts could lead to legacy effects on growth (Anderegg et al. 2015; Szejner et al 2020). The interactions are highlighted between spring temperatures and summer droughts and their influence on atmospheric water demand that strongly influence conifer resilience in drought-prone environments (Ren et al. 2019), whereas oak species appear to be more drought tolerant and may show a faster post-drought recovery. Different durations of drought and recovery periods could also contribute to pine-oak coexistence and should be further investigated.

Conclusions

Our results provide a unique study of xylogenesis in four species coexisting in a mixed pine–oak forest under semi-arid conditions, providing new insights on how trees face intra-annual climate variability in areas of marked drought seasonality. It was shown that species differentially responded to climate contributing to their coexistence. In general, warm night conditions and high evaporation rates during spring and summer enhanced xylem formation, but pine species showed more response than the oak. The species with the highest growth rate was P. leiophylla which had an early start of radial growth but a shorter xylogenesis than P. cembroides and P. engelmannii. A lower second growth peak was in August and September, corresponding to a bimodal pattern, and attributed to a decrease in evaporative demand and an increase in soil moisture after summer monsoon rains. Temperature played a critical factor as a climate driver of xylogenesis in semi-arid forests, despite the rate, timing, and duration of xylogenesis phases among coexisting species. The capacity of each species to adjust to climate variability determines their vulnerability or resilience to tolerate hotter droughts forecasted under warmer climate scenarios.

References

Acosta-Hernández AC, Pompa-García M, Camarero JJ (2017) An updated review of dendrochronological investigations in Mexico, a megadiverse country with a high potential for tree-ring sciences. Forests 8:160

Acosta-Hernández AC, Pompa-García M, Camarero JJ (2019) Seasonal growth responses to climate in wet and dry conifer forests. IAWA J 40:311-S1

Aguilar JM, Boecklen WJ (1992) Patterns of herbivory in the Quercus grisea × Quercus gambelii species complex. Oikos 64:498–504

Aguilar-Romero R, Pineda-García F, Paz H, Gonzalez-Rodriguez A, Oyama K (2017) Differentiation in the water-use strategies among oak species from central Mexico. Tree Physiol 37:915–925

Anderegg WRL, Schwalm C, Biondi F, Camarero JJ, Koch G, Litvak M, Ogle K, Shaw JD, Shevliakova E, Williams AP, Wolf A, Ziaco E, Pacala S (2015) Pervasive drought legacies in forest ecosystems and their implications for carbon cycle models. Science 349:528–532

Antonova GF, Stasova VV (1993) Effects of environmental factors on wood formation in Scots pine stems. Tree Struct Funct 7:214–219

Bickford IN, Fulé PZ, Kolb TE (2011) Growth sensitivity to drought of co-occurring Pinus spp. along an elevation gradient in northern Mexico. West N Am Nat 71:338–348

Buttò V, Deslauriers A, Rossi S, Rozenberg P, Shishov V, Morin H (2020) The role of plant hormones in tree-ring formation. Tree Struct Funct 34:315–335

Camarero JJ, Olano JM, Parras A (2010) Plastic bimodal xylogenesis in conifers from continental Mediterranean climates. New Phytol 185:471–480

Carlón Allende T, Mendoza ME, Villanueva Díaz J, Li Y (2018) Climatic response of Pinus cembroides Zucc. radial growth in Sierra del Cubo, Guanajuato Mexico. Tree Struct Funct 32:1387–1399

Cavender-Bares J (2016) Diversity, distribution, and ecosystem services of the North American oaks. Int Oaks 27:37–48

Chesson P, Huntly N (1997) The roles of harsh and fluctuating conditions in the dynamics of ecological communities. Am Nat 150:519–553

Corcuera L, Camarero JJ, Gil-Pelegrín E (2004a) Effects of a severe drought on growth and wood-anatomical properties of Quercus faginea. IAWA J 25:185–204

Corcuera L, Camarero JJ, Gil-Pelegrín E (2004b) Effects of a severe drought on Quercus ilex radial growth and xylem anatomy. Tree Struct Funct 18:83–92

Cuny HE, Rathgeber CBK, Frank D, Fonti P, Mäkinen H, Prislan P, Rossi S, Martinez del Castillo E, Campelo F, Vavrčík H, Camarero JJ, Bryukhanova MV, Jyske T, Gričar J, Gryc C, De Luis M, Vieira J, Čufar K, Kirdyanov AV, Oberhuber W, Treml V, Huang JG, Li X, Swidrak I, Deslauriers A, Liang E, Nöjd P, Gruber A, Nabais C, Morin H, Krause C, King G, Fournier M (2015) Woody biomass production lags stem-girth increase by over one month in coniferous forests. Nat Plants 15160:1–6

Del Castillo J, Comas C, Voltas J, Ferrio JP (2016) Dynamics of competition over water in a mixed oak-pine Mediterranean forest: spatio-temporal and physiological components. For Ecol Manage 382:214–224

Denne MP (1989) Definition of latewood according to Mork (1928). IAWA J 10:59–62

Deslauriers A, Rossi S, Liang E (2015) Collecting and processing wood microcores for monitoring xylogenesis. In: Yeung ECT, Stasolla C, Sumner MJ, Huang BQ (eds) Plant microtechniques and protocols. Springer, Cham, pp 417–429

Etzold S, Sterck F, Bose AK, Braun S, Buchmann N, Eugster W, Gessler A, Kahmen A, Peters RL, Vitasse Y, Walthert L, Ziemińska K, Zweifel R (2022) Number of growth days and not length of the growth period determines radial stem growth of temperate trees. Ecol Lett 25:427–439

Fallon B, Cavender-Bares J (2018) Leaf-level trade-offs between drought avoidance and desiccation recovery drive elevation stratification in arid oaks. Ecosphere 9:e02149-25

Farjon A, Styles BT (1997) Pinus (Pinaceae). Flora Neotropica Monograph 75. The New York Botanical Garden, New York

Fonti P, Von Arx G, García-González I, Eilmann B, Sass-Klaassen U, Gärtner H, Eckstein D (2010) Studying global change through investigation of the plastic responses of xylem anatomy in tree rings. New Phytol 185:42–53

Frankenstein C, Eckstein D, Schmitt U (2005) The onset of cambium activity: a matter of agreement? Dendrochronologia 23:57–62

Galicia L, Potvin C, Messier C (2015) Maintaining the high diversity of pine and oak species in Mexican temperate forests: a new management approach combining functional zoning and ecosystem adaptability. Can J for Res 45:1358–1368

Gao J, Yang B, Peng X, Rossi S (2021) Tracheid development under a drought event producing intra-annual density fluctuations in the semi-arid China. Agric For Meteorol 308–309:108572

García-Cervigón AI, Camarero JJ, Cueva E, Espinosa CI, Escudero A (2019) Climate seasonality and tree growth strategies in a tropical dry forest. J Veg Sci 31:266–280

Garcia-Forner N, Vieira J, Nabais C, Carvalho A, Martínez-Vilalta J, Campelo F (2019) Climatic and physiological regulation of the bimodal xylem formation pattern in Pinus pinaster saplings. Tree Physiol 39:2008–2018

Gernandt DS, Pérez de la Rosa JA (2014) Biodiversidad de Pinophyta (coníferas) en México. Revist Mexicana De Biodivers 85:126–133

González-Casares M, Pompa-García M, Camarero JJ (2016) Differences in climate–growth relationship indicate diverse drought tolerances among five pine species coexisting in Northwestern Mexico. Tree Struct Funct 31:531–544

González-Elizondo MS, González-Elizondo M, Tena-Flores JA (2012) Vegetación de la Sierra Madre Occidental, México: una síntesis. Acta Bot Mexicana 100:351–403

González-González BD, Rozas V, García-González I (2014) Earlywood vessels of the sub-Mediterranean oak Quercus pyrenaica have greater plasticity and sensitivity than those of the temperate Q. petraea at the Atlantic-Mediterranean boundary. Tree Struct Funct 28:237–252

Griffin D, Woodhouse CA, Meko DM, Stahle DW, Faulstich HL, Carrillo C, Touchan R, Castro CL, Leavitt SW (2013) North American monsoon precipitation reconstructed from tree-ring latewood. Geophys Res Lett 40:954–958

Grossiord C, Buckley TN, Cernusak LA, Novick KA, Poulter B, Siegwolf RTW, Sperry JS, McDowell NG (2020) Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol 226:1550–1566

Gutiérrez E, Campelo F, Camarero JJ, Ribas M, Muntán E, Nabais C, Freitas H (2011) Climate controls act at different scales on the seasonal pattern of Quercus ilex L. stem radial increments in NE Spain. Tree Struct Funct 25:637–646

Herrera-Soto G, González-Cásares M, Pompa-García M, Camarero JJ, Solís-Moreno R (2018) Growth of Pinus cembroides Zucc. in response to hydroclimatic variability in four sites forming the species latitudinal and longitudinal distribution limits. Forests 9:440

Hipp AL, Manos PS, Gonzalez-Rodriguez A, Hahn M, Kaproth M, McVay JD, Avalos SV, Cavender-Bares J (2018) Sympatric parallel diversification of major oak clades in the Americas and the origins of Mexican species diversity. New Phytol 217:439–452

Little EL (1950) Southwestern trees: A guide to the native species of New Mexico and Arizona. Agriculture Handbook No. 9. USDA, Forest Service, Washington. p 109

Martin MP, Peters CM, Asbjornsen H, Ashton MS (2021) Diversity and niche differentiation of a mixed pine–oak forest in the Sierra Norte, Oaxaca. Mexico Ecosphere 12:e03475

Martín-Benito D, Beeckman H, Cañellas I (2013) Influence of drought on tree rings and tracheid features of Pinus nigra and Pinus sylvestris in a mesic Mediterranean forest. Eur J for Res 132:33–45

Morino K, Minor RLBarron-Gafford GA, Brown PM, Hughes MK (2021) Bimodal cambial activity and false-ring formation in conifers under a monsoon climate. Tree Physiol 41:1893–1905

Oberhuber W, Landlinger-Weilbold A, Schröter DM (2021) Triggering bimodal radial stem growth in Pinus sylvestris at a drought-prone site by manipulating stem carbon availability. Front Plant Sci 12:674438

Pasho E, Camarero JJ, Vicente-Serrano SM (2012) Climatic impacts and drought control of radial growth and seasonal wood formation in Pinus halepensis. Tree Struct Funct 26:1875–1886

Pérez-de-Lis G, Rossi S, Vázquez-Ruiz RA, Rozas V, García-González I (2016) Do changes in spring phenology affect earlywood vessels? Perspective from the xylogenesis monitoring of two sympatric ring-porous oaks. New Phytol 209:521–530

Pompa-García M, Camarero JJ, Colangelo M, Gallardo-Salazar JL (2021) Xylogenesis is uncoupled from forest productivity. Tree Struct Funct 35:11123–1134

Pompa-García M, Camarero JJ, Colangelo M, González-Casares M (2021b) Inter and intra-annual links between climate, tree growth and NDVI: improving the resolution of drought proxies in conifer forests. Int J Biometeorol 65:2111–2121

Ren P, Ziaco E, Rossi S, Biondi F, Prislan P, Liang E (2019) Growth rate rather than growing season length determines wood biomass in dry environments. Agric For Meteorol 271:46–53

Rossi S, Deslauriers A, Anfodillo T (2006) Assessment of cambial activity and xylogenesis by micro sampling tree species: an example at the Alpine timberline. IAWA J 27:383–394

Rossi S, Deslauriers A, Griçar J, Seo JW, Rathgeber CB, Anfodillo T, Morin H, Levanic T, Oven P, Jalkanen R (2008) Critical temperatures for xylogenesis in conifers of cold climates. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 17:696–707

Schwinning S, Kelly C (2013) Plant competition, temporal niches and implications for productivity and adaptability to climate change in water-limited environments. Funct Ecol 27:886–897

Seager R, Ting M, Davis M, Cane M, Naik N, Nakamura J, Li C, Cook E, Stahle D (2009) Mexican drought: an observational modeling and tree ring study of variability and climate change. Atmósfera 22:1–31

Szejner P, Belmecheri S, Ehleringer JR, Monson RK (2020) Recent increases in drought frequency cause observed multi-year drought legacies in the tree rings of semi-arid forests. Oecologia 192:241–259

Vaganov EA, Hughes MK, Shashkin AV (2006) Growth dynamics of conifer tree rings. Images of past and future environments. Springer, New York

Vieira J, Carvalho A, Campelo F (2020) Tree growth under climate change: evidence from xylogenesis timings and kinetics. Front Plant Sci 11:90

Zeng Q, Rossi S, Yang B, Qin C, Li G (2020) Environmental drivers for cambial reactivation of Qilian Junipers (Juniperus przewalskii) in a semi-arid region of Northwestern China. Atmosphere 11:232

Zhang J, Gou X, Manzanedo RD, Zhang F, Pederson N (2018) Cambial phenology and xylogenesis of Juniperus przewalskii over a climatic gradient is influenced by both temperature and drought. Agric For Meteorol 260:165–175

Zhang J, Alexander MR, Gou X, Deslauriers A, Fonti P, Zhang F, Pederson N (2020) Extended xylogenesis and stem biomass production in Juniperus przewalskii Kom. during extreme late-season climatic events. Ann For Sci 77:1–11

Ziaco E, Biondi F, Rossi S, Deslauriers A (2016) Environmental drivers of cambial phenology in Great Basin bristlecone pine. Tree Physiol 36:818–831

Ziaco E, Truettner C, Biondi F, Bullock S (2018) Moisture-driven xylogenesis in Pinus ponderosa from a Mojave desert mountain reveals high phenological plasticity. Plant Cell Env 41:823–836

Zweifel R, Sterck F, Braun S, Buchmann N, Eugster W, Gessler A, Häni M, Peters RL, Walthert L, Wilhelm M, Ziemińska K, Etzold S (2021) Why trees grow at night. New Phytol 231:2174–2185

Acknowledgements

We thank Marco González-Cásares, Andrea Acosta-Hernández, José Luis Gallardo-Salazar, Eduardo Vivar-Vivar and José Alexis Martínez Rivas for their support during field work.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Project funding: This study was funded by the Mexican CONACYT (Grant Number CB-2013/222522-A1-S-21471) and the Mexican dendroecology network (https://dendrored.ujed.mx).

The online version is available at http://www.springerlink.com

Corresponding editor: Yanbo Hu.

Guest editor: Yanbo Hu.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pompa-García, M., Camarero, J.J. & Colangelo, M. Different xylogenesis responses to atmospheric water demand contribute to species coexistence in a mixed pine–oak forest. J. For. Res. 34, 51–62 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-022-01484-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-022-01484-3