Abstract

Palm oil (PO) is an important source of livelihood, but unsustainable practices and widespread consumption may threaten human and planetary health. We reviewed 234 articles and summarized evidence on the impact of PO on health, social and economic aspects, environment, and biodiversity in the Malaysian context, and discuss mitigation strategies based on the sustainable development goals (SDGs). The evidence on health impact of PO is equivocal, with knowledge gaps on whether moderate consumption elevates risk for chronic diseases, but the benefits of phytonutrients (SDG2) and sensory characteristics of PO seem offset by its high proportion of saturated fat (SDG3). While PO contributes to economic growth (SDG9, 12), poverty alleviation (SDG1, 8, 10), enhanced food security (SDG2), alternative energy (SDG9), and long-term employment opportunities (SDG1), human rights issues and inequities attributed to PO production persist (SDG8). Environmental impacts arise through large-scale expansion of monoculture plantations associated with increased greenhouse gas emissions (SDG13), especially from converted carbon-rich peat lands, which can cause forest fires and annual trans-boundary haze; changes in microclimate properties and soil nutrient content (SDG6, 13); increased sedimentation and change of hydrological properties of streams near slopes (SDG6); and increased human wildlife conflicts, increase of invasive species occurrence, and reduced biodiversity (SDG14, 15). Practices such as biological pest control, circular waste management, multi-cropping and certification may mitigate negative impacts on environmental SDGs, without hampering progress of socioeconomic SDGs. While strategies focusing on improving practices within and surrounding plantations offer co-benefits for socioeconomic, environment and biodiversity-related SDGs, several challenges in achieving scalable solutions must be addressed to ensure holistic sustainability of PO in Malaysia for various stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The African oil palm (OP) Elaeis guineensis is a vital source of edible oil, derived from its mesocarp and kernel. Malaysia (26%) and Indonesia (58%) are the largest global palm oil (PO) producers, which together accounted for 84% of globally produced PO in 2021 (USDA 2021). These countries are also global emerging economies that belong to the world's biodiversity hotspots (Myers et al. 2000). Hence, while the rise and expansion of OP as a cash crop has fueled the industry and economy (Qaim et al. 2020; Karki et al. 2018), it has come at significant costs to the region's rainforests and biodiversity (Qaim et al. 2020; Vijay et al. 2016), including violations of land rights towards indigenous peoples (Buckland 2005; Sheil et al. 2009). These drawbacks have led to calls for boycotts, anti-PO campaigns and governmental policies, particularly from the European Union, North America, Australia, and New Zealand (Walden 2019). Additionally, the use of PO is debated due to perceived and documented adverse effects on human health, both on nutritional aspects of widespread dietary consumption, and societal aspects in terms of rights of workers and local communities living in plantation landscapes (Qaim et al. 2020).

Arguably, any crop that is cultivated unsustainably inflicts damage to ecosystems and biodiversity due to deforestation, excessive fertilizer usage, pesticide runoffs and negative effect of monocropping on soil and ecosystem resilience (Asher 2019). This was seen in the cultivation of other major crops, such as the rampant deforestation for cattle soy-feed in the Amazon between 1996–2005 or the toxic algae bloom of Lake Erie in 2014 culminating from decades of pesticide and fertilizer runoff from corn crops (Macedo et al. 2012; Nepstad et al. 2014). However, blanket measures to address negative impacts of PO production may undermine the complexity of issues surrounding OP cultivation and the PO industry, and hamper concerted international efforts towards achieving various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Hinkes and Christoph-Schulz 2020).

While negative impacts of excessive consumption and unsustainable agricultural practices seem indubitable, what constitutes as sustainable practices and their ability to mitigate associated negative issues is less well-defined, exposing significant knowledge gaps in efforts to develop more effective sustainability policies for PO. Thus, this review aims to (1) summarize the available evidence on the impact of PO production and consumption on human health, social and economic aspects, environment, and biodiversity in the Malaysian context, and (2) discuss efforts to mitigate negative impacts and identify SDG-related co-benefits and trade-offs of different mitigation strategies.

Impact of Malaysian palm oil

The impact of PO was summarized based on a systematic search using PRISMA (http://www.prisma-statement.org/) guidelines, with manual addition of relevant contextual articles and reports resulting in a total of 276 full texts reviewed (Supplement, Figure S1). The various impacts of PO were categorized broadly under health, socioeconomics, environment, and biodiversity (in the Malaysian context), and then mapped to specific SDG keywords (Fonseca et al. 2020).

Nutritional impact of palm oil consumption

Palm oil is used ubiquitously as cooking oil in different Asian and West African cuisines because it is tasteless, odorless, and has a high smoke-point, which makes it safe for re-frying (Boateng et al. 2016). Due to its naturally occurring partially hydrogenated fats (Magri et al. 2015), PO results in crunchiness, palatability, and preservation properties in manufacturing (Di Genova et al. 2018), without posing the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) associated with industrially produced partially hydrogenated vegetable oils (Odia 2015; Magri et al. 2015). As such, PO-derivatives are commonly found in biscuits, noodles, and bakery products worldwide (Boateng et al. 2016). The health effects of widespread PO consumption remain contentious. Some studies cite adverse effects of saturated fats (Kadandale et al. 2019), while others tout protective effects on cardiovascular health, antidiabetic and anticancer properties, and reproductive health improvement (Giri and Bhatia 2020; Ibrahim et al. 2020a, b) due to PO-derived phytonutrients such as tocotrienols and carotenoids, which is converted into an important micronutrient, Vitamin A.

Phytonutrients and oxidative stability (SDG2)

Red PO (RPO) is known to possess pro-vitamin A activity (Loganathan et al. 2017) and used in vitamin A fortification programs due to its resistance to oxidation and stability (Pignitter et al. 2016). However, RPO trials for preventing Vitamin A deficiency, a key factor in preventable blindness and severe infection in low-income countries, have garnered inconsistent results, with some reporting RPO supplementation effective, and others concluding a lack of significant effects (Dong et al. 2017). Nevertheless, compared to RPO, which retains 80% of its vitamins and carotenoids, most PO consumed as cooking oil or in processed food is refined, bleached, and contains less phytonutrients.

Palm oil also contains relatively high amounts of tocotrienols, a form of vitamin E known to scavenge free radicals for prevention of pathologies (Jegede et al. 2015). Animal studies on PO tocotrienol rich fraction (TRF) suggest beneficial effects such as prevention of bone loss (Wong et al. 2018), amelioration of Alzheimer’s related behavior and cognitive impairments (Durani et al. 2018), and improvement in antioxidant levels through modulation activity of antioxidant enzymes (Nor Azman et al. 2018). However, these benefits have not been convincingly observed in human trials such as those on TRF treatment in diabetes (Tan et al. 2018).

Saturated fats and contaminants (SDG3)

Adverse health impacts of PO are related to its saturated fatty acid (SFA) content, whereby the carbon chain “saturated” with hydrogen purportedly increases low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, reduces fat oxidation (Yajima et al. 2018), and elevates risk of CVD. However, the majority of SFA in PO is palmitic acid (44%), known to be less potent in raising LDL cholesterol, unlike lauric and myristic acids, which are present in trace amounts (Magri et al. 2015; Boateng et al. 2016).

The association between PO carbon chain saturation and increased risk of CVD is subject to debate. Some claim unsaturation (at the sn-2 position) alters PO characteristics to mimic monounsaturated oils such as olive oil, instead of harmful saturated animal fats (Sin Teh et al. 2018). Others claim that the degree of saturation has a greater effect on blood lipid concentration than the positional distribution of SFAs (Sun et al. 2015). A randomized trial studying the effects of hybrid PO supplementation on human plasma lipid patterns concluded that effects on plasma lipids were comparable to extra virgin olive oil, which is typically consumed for its protective effects on cardiovascular health (Lucci et al. 2016), although notably, the study evaluated crude HPO (from E. guineensis and E. oleifera), which differs from refined PO in its content of vitamin E and carotenoids.

In animal studies including murids and fish, high-fat diets of PO and/or consumption of polar compounds from deep-frying of PO were associated with elevated levels of LDL, triglycerides (Sales et al. 2019; Larbi et al. 2018), and alkaline phosphatase-induced liver lipid accumulation (Janssens et al. 2015), changes in offspring's adipose tissue in adult life (Magri et al. 2015), and impaired glucose tolerance (Li et al. 2017). Conversely, PO supplementation in sheep feed has been shown to reduce SFA content, thus increasing mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acid content in sheep milk (Bianchi et al. 2017).

The evidence appears more equivocal in humans, especially under conditions of regular consumption. A systematic review by Ismail et al. (2018) challenged the link between PO consumption and the elevation of LDL concluding the lack of strong evidence for increased risk of CVD (Ismail et al. 2018), while an earlier systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials by Sun et al. (2015) concluded that PO consumption results in higher LDL cholesterol compared to vegetable oils low in saturated fat, but results in higher HDL cholesterol compared to trans-fat-containing oils in humans. These reviews are notably limited by a small number of studies and publication biases based on funding source, widespread consumption, and difficulty to single out PO from other food items (Ismail et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2015). A recent randomized controlled-feeding trial in healthy normocholesterolemic adults showed that butter raised LDL cholesterol higher than palm stearin regardless of background consumption of carbohydrate and fat (Hyde et al 2021). Thus far, the oft-cited negative effects of saturated fats from PO remains inconclusive.

Finally, processing and manufacturing issues, especially for non-branded oils known to contain less favorable SFA composition (Aung et al. 2018) and increased PO contaminants pose additional health risks. However, such risks may be mitigated with improved industry standards and regulation (Di Genova et al. 2018). Ultimately, consumption of PO, especially in a healthy balanced diet, does not appear to pose significant elevated risk for chronic diseases such as CVD, diabetes, and cancer in adult or pediatric populations (Odia 2015; Di Genova et al. 2018; Mancini et al. 2015; Marangoni et al. 2017; Bronsky et al. 2019). Reducing PO consumption by 50% is predicted to only have a relatively small impact on health (Jensen et al. 2019), unless it is part of a broader dietary and nutritional strategy to achieve significant improvements in health.

Social and economic impacts of the palm oil industry

National economic growth (SDG9, 12)

Most plantations in Malaysia are large-scale plantations with 61% of these plantations belonging to private estates, 22% governed under governmental schemes (half of which, belong to smallholders (van Leeuwen 2019), i.e., family-based plantations of less than 50 ha) and 17% owned by independent smallholders (MPOB 2017). Smallholders produce PO independently and sell their produce directly to a mill or through various governmental schemes (RSPO 2018). More than 300,000 smallholders, including farmers of indigenous tribes both in East and West Malaysia, contribute to more than 18 Mio t of annually exported PO (Hamid et al. 2013). Although, OP agriculture is commonly associated with Borneo, in 2017 Peninsular Malaysia contributed a larger fraction of Malaysia’s total PO products (ca. 52%) (MPOB 2018; Shevade and Loboda 2019).

Approximately 30% of all globally produced vegetable oils is PO, accounting for two thirds of exported oils by volume (Shevade and Loboda 2019). Increasing demand from China and India stimulated the rapid growth of the PO industry, with Malaysia supplying 44% of globally exported PO (MPOB 2017; Shevade and Loboda 2019; Brandi et al. 2015). Through a series of policies, including the implementation of New Key Economic Areas for PO (Jomo and Rock 1998; Pemandu 2010), Malaysia has further fostered domestic PO refining businesses, achieving a refining capacity of 26.5 Mio t pa exceeding its annual CPO production (MPOB 2020). The PO sector also draws foreign investments to Malaysia (Mekhilef et al. 2011; Shevade and Loboda 2019) and earnings through corporate taxes (Mahat 2012). Since 2008, the industry contributed ca. MYR65.2bil (ca. USD16bil) in exports (Mekhilef et al. 2011; MPOB 2017), and by 2015, PO contributed to 4.2% of Malaysia's GDP (Shevade and Loboda 2019), and currently 37.7% of agricultural GDP (DOSM 2020).

Poverty alleviation and food security (SDG1, 8, 10)

Since the 1950s, the PO industry has been a catalyst for development (Awang Ali et al. 2011; Arif and Tengku Mohd Ariff 2001; Mahat 2012), becoming a major employer and key contributor to rural growth in Malaysia (Feintrenie et al. 2010; Rist et al. 2010; Lee et al. 2014; Castiblanco et al. 2015; Gatto et al. 2017; Choiruzzad 2019; Arif and Tengku Mohd Ariff 2001). Since 1956, progressive land expansion schemes led by the Federal Land Development Agency (FELDA) aimed to develop plantation land for the landless and rural poor Malays (Teoh 2002) and increased smallholder income from traditional crops (Awang Ali et al. 2011; Mahat 2012). With ca. 85 k ha of developed land and resettling of ca. 110 k families (Ahmad Tarmizi 2008), FELDA has contributed to poverty alleviation amongst settlers with the reported average monthly household income of FELDA smallholders increased from MYR1338 in 2006 to MYR3000 in 2010, exceeding the national poverty limit of MYR720 per month (Ahmad Tarmizi 2008).

The PO industry employs approximately 2.3 million people in Malaysia (Mahat 2012), contributing to Malaysia’s low unemployment rate of ca. 3.4%, which only recently increased to 4.6% due to the COVID-19 pandemic (DOSM 2021). Insufficient local labor supply has also led to an influx of one million foreign workers from neighboring developing countries who are mainly employed in plantations and mills (Basiron 2011), including smallholder plantations (Awang Ali et al. 2011) but recruitment activities in the PO industry have stalled since the pandemic. The plantation sector employs more than 70% foreign workers and the ongoing national and international travel restrictions imposed to curb the impacts of the pandemic have caused labor shortages by 500,000 workers, resulting in a 3.8% decrease in PO production between 2019 and 2020. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has also led to a decline of PO exports from 18.5 Mio Mt in 2019 to 17.4 Mio Mt in 2020 (MPOC 2020).

In rural areas with limited job opportunities, government incentives enabled farmers to develop their plantations (Asmit and Koesrindartoto 2018) while simultaneously increasing employment opportunities. The labor-intensive plantation sector only has low level mechanization; thus, workers are required for fruit harvesting, collection, and other fieldworks (Ismail 2013). Growing OP is also a lucrative and popular side crop for farmers of other lower-yielding but government-incentivized agricultural crops such as paddy (Alam et al. 2010). Small growers often practice mixed farming by raising livestock and cultivating fruits and vegetables at the OP plantations, enhancing income opportunities (Ashraf et al. 2018). Consequently, OP cultivation along with mixed agricultural activities are associated with improved standard of living throughout the country, narrowing the income gap between rural and urban workforce (Mahat 2012; Hamid et al. 2013; Man et al. 2013). However, smallholders in less accessible areas suffer land shortage and encroachment from nearby estates, rendering them more vulnerable to fluctuations in crude PO prices (Azhar et al. 2020).

Poverty and food security are inextricably linked, and the PO industry generally contributes to both increased employment and food security in Malaysia and globally, as PO remains the world’s most affordable edible vegetable oil, and a staple in low-middle income countries across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East (Boateng et al. 2016). Improved income arising from agricultural activities such as rubber and OP cultivation, in combination with traditional hunting and gathering activities, appears to be associated with lower risk of malnutrition among certain indigenous tribes, such as the Jah Hut in Pahang (Law et al. 2020). However, OP plantation expansion has negative impact on rural and indigenous food security when land rights of these rural communities are violated (Nesadurai 2013).

Social conflicts and adverse impact on indigenous peoples (SDG8)

Conflicts are common between indigenous peoples in Malaysia and large companies who were granted development permits in forest reserves, while low wages and/or human rights violations of foreign plantation workers continue to tarnish the reputation of the industry (Wan Daud et al. 2020). Oil palm expansion may also contribute to rising inequality among farmers or between communities (Gatto et al. 2017; Cramb and McCarthy 2016), especially when farmers are forced to sell their land, consequently losing means for their own agricultural production (Bou Dib et al. 2018; McCarthy 2010).

In Sabah and Sarawak, most plantations are on steep hills that were converted from agricultural land with slash-and-burn techniques (Wicke 2011). Traditionally, burning of plant material in old plantations to get rid of unwanted plant waste can enhance nutrient availability in depleted soils (Knicker 2007), but this technique has led to dramatic haze problems throughout Southeast Asia (Padfield et al. 2016), and directly reduced the life quality of farmers living in affected areas (Obidzinski et al. 2012). Many communities that depend on ecosystem services such as clean rivers, natural forest products and/or small-scale agricultural activities for income are highly affected by land conversion, as they lose access to these resources (Martin 2017; Awang Ali et al. 2011; Mahat 2012). Furthermore, chemical fertilizers and pesticides used in large-scale plantations may pollute freshwater resources that are essential to indigenous and rural communities (Obidzinski et al. 2012; Bou Dib et al. 2018; Dudgeon et al. 2006).

The emphasis for commodity crops such as OP and rubber and the rapid expansion of plantations and intensive logging may have indirectly contributed toward poverty and heightened vulnerability of some indigenous peoples in Malaysia (Kari et al. 2016; Wan Daud et al. 2020). Barriers in technology and knowledge transfer to indigenous farmers and small growers renders them less empowered to use best practices that can improve yield while minimizing practices with adverse impacts, such as slash and burn for clearing of old OP trees (Rochmyaningsih 2015). Indigenous small growers also suffer more threats from wild animals, given that they tend to cultivate farms close to forests (Law et al. 2018). Such threats to safety often contribute to agricultural failure, and consequent food insecurity among indigenous people.

Impact of oil palm cultivation on the environment and biodiversity

Land use policies in Malaysia are regulated by the state governments. Half of all plantations are planted on state forest land that was previously used for rubber or other uses (Hansen et al. 2014; Padfield et al. 2019). From 2010 to 2018, OP plantations reportedly increased by 5.06 Mha at a growth rate of 83.5%, with growth rates for East and West Malaysia at 109.5% and 62.1%, respectively (Li et al. 2020). The deforestation for new OP plantations between 2001 and 2017 reached 5.98 Mha accounting for 68.2% of the total amount of deforestation in Malaysia for that period (Li et al. 2020). While west Malaysian plantations mostly expanded on former rubber plantations (Barlow 1997), in Sabah and Sarawak, plantation expansion has driven deforestation with 4.2 Mha of old growth forest cleared between 1973 and 2015 (Gaveau et al. 2016). Compared to Indonesia, Malaysia had a more rapid conversion rate of these cleared lands of ca. 60% within a 5-year time frame (Gaveau et al. 2016).

Specifically for peatlands, plantation area reportedly increased by ca. 200 kha between 2003 and 2008 (Edwards et al. 2010), amounting to one-third of the total new plantations, with the majority occurring in Sarawak (Edwards et al. 2010). However, Gunarso et al. (2013) reported a lower estimate of 13% of OP planted on peatland in 2010. Records from a 250 m spatial resolution map showed that more than 800 kha of Malaysian tropical peat swamp have been converted to OP plantations (Koh et al. 2011). Specifically, Sarawak and Sabah had 49.5% and 34.6% of peatlands covered by OP, respectively, in 2015 (Miettinen et al. 2017). However, since 2015, over 90% of internationally traded PO followed producer commitments for the ‘no deforestation and no peat’ policy (Austin et al. 2015; Butler 2015). More recently, Wan Mohd Jaafar et al. (2020) reported declined conversion of peatland to plantation by 20.5% and 19.1% in Sarawak and Sabah, respectively.

Land use change for agriculture is associated with adverse impacts on the environment through increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, soil erosion, and microclimate and regional climate changes, i.e., change in temperature and precipitation, and increased risk of flooding (Gaveau et al. 2014; Uning et al. 2020; Wolf 1996).

Emissions, soil, and climate (SDG6, 13).

Malaysia is the fourth highest carbon emitter from forest degradation with over 140 Mio t CO2 pa after Indonesia, Brazil and India (Harris et al. 2012; Pearson et al. 2017; Begum et al. 2020). The conversion of forest into OP plantations reduced carbon stocks by over 50% and increased GHG emissions by four times, compared to land converted from old rubber plantations (Kusin et al. 2017). Plantations on peat in Malaysia emit GHG ranging from 12.4 up to 76.6 t CO2-eq ha−1 pa (Hashim et al. 2018), with highest emissions recorded in Selangor (65 t C ha−1) in 2006, and the lowest in Sarawak (7 t C ha−1) (Matysek et al. 2018; Melling et al. 2005, 2008, 2013). Cooper et al. (2020) suggest that conversion of peat swamp forest in Malaysia contributes between 16.6 and 27.9% (95% CI) of combined total national GHG emissions. CO2 release from drained peatland is higher than from mineral soils as peat stocks hold higher quantities of carbon (Choo et al. 2011; Hashim et al. 2018; Page et al. 2011). This loss of stocked carbon increases during the dry season, facilitated by longer and more intense dry seasons associated with current global climate emergency (Matysek et al. 2018). Additionally, plantations on peatlands lead to degradation and fires (Page and Hooijer 2016; Page et al 2009), which are associated with significant air pollution and threats to human health in the region (Uda et al. 2019; Crippa et al. 2016).

While OP plantations and associated cultivation practices emit up to two times more CO2 than other crops, they also absorb CO2 and produce around 18 t O2 ha−1 pa (Uning et al. 2020). The emission difference between different croplands depends on the type of soil and amount of carbon stocks, drainage and fertilizer use, and methane use at the mills (Hashim et al. 2018). However, CO2 uptake above OP canopy of 82 t C ha−1 pa was recorded in Sabah and this is reportedly higher than from intact forests (32 t C ha−1 pa) (Fowler et al. 2011; Sharvini et al. 2020), suggesting potential carbon neutrality of OP cultivated lands (Kusin et al. 2017).

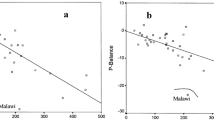

Plantations’ nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions are lower than those of primary forests as forest soils are a better source of N2O than plantations (Yashiro et al. 2007). Newly established OP plantations show slightly higher N2O emissions than older plantations due to the use of fertilizers and other environmental factors (Melling et al. 2007; Yashiro et al. 2008), but overall N2O emission levels seem similar in OP plantations of different ages (Kusin et al. 2017). Consistent with other studies (Holzinger et al. 2002), emissions of isoprene (C5H8), CO2, and surface ozone (O3) from OP plantations in Pahang were temperature-dependent, with lower emission during cooler temperatures at night (Uning et al. 2020). Increased NOx emissions over plantations are caused by fertilizer and PO plant combustion and vehicle exhausts (Uning et al. 2020).

Evapotranspiration processes, but not the amount of precipitation, are impacted by land conversion from forests into OP plantations (Amin et al. 2016). Oil palms planted on steep terrain cause negative hydrological impacts such as increased flooding risk, modification of river ecology, and sedimentation (Nainar et al. 2018; Saadatkhah et al. 2016). Soil mineralization rates are similar between OP plantations and forests in Sabah (Hamilton et al. 2016) with approximately 90% reduction of denitrification and anaerobic ammonium oxidation disrupting nitrogen gas (N2) production. Consequently, high nitrate concentration occurs in ground water of OP plantations, due to the application of N-fertilizers (Sheikhy et al. 2018).

Changes in microclimate directly impact plant growth and soil nutrient processes, with the temperature inside plantations increased by 6.5 °C compared to primary forest in Sabah (Hardwick et al. 2015). The change in regional climate manifests through increased rainfall, temperature, radiation, atmospheric pressure, cloud cover, and a decrease in evaporation, relative humidity, sunshine hours, and wind speed due to intensive land use change in the Kelantan River Basin between 1984 and 2014, which follows trends found across Malaysia (Nurhidayu and Hakeem 2017).

Biodiversity (SDG14, 15)

There is still poor understanding of how species respond to anthropogenic disturbance in tropical primary forests (Silmi et al. 2013; Fitzherbert et al. 2008) but biodiversity decline of different species of arthropods, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals in Malaysia due to the expansion of plantations into natural habitats is well documented (Vijay et al. 2016; Brandon-Mong et al. 2018). Some indicator species may predict changes in diversity and geographical distinctness in relation to habitat disturbance. For example, fruit-eating butterfly abundance in Sabah was lowest in OP plantations compared to primary and logged-over forest (Koh and Wilcove 2008), and species richness was lower in areas converted from primary or secondary forest to OP plantations compared to conversion from existing rubber to OP plantations (Koh and Wilcove 2008; Hamer et al. 2003). Oil palm plantations in Sabah showed lower species richness of ants compared to riparian reserves and logged forests (Fayle et al. 2010; Gray et al. 2015). Most ant species in plantations were non-forest species (Brühl and Eltz 2010), suggesting that conversion of forest into plantations results in replacement of native forest ant species with more dominant invasive species. However, when assessing the ratio between regional and local species at a large spatial scale, more common and abundant species of ants were found in OP plantations than forests (Wang and Foster 2015).

Species richness of freshwater fishes was lower in rivers near OP plantations in Bintulu, Sarawak (Kano et al. 2020), and species diversity of amphibians (i.e. order Anura) was lower at OP plantations in Selangor compared to grassland, coconut plantation, and primary forest (Faruk et al. 2013). Similarly, anuran species richness was higher in primary and secondary forest habitats compared with OP plantations in Sabah (Aguilar-León 2020).

Less than 50 species of forest birds were recorded in OP plantations in Sabah demonstrating the lowest diversity compared with primary forest, logged forest and rubber plantation (Koh and Wilcove 2008). The diversity and density of insectivorous and frugivorous bird species were also lowest in OP plantations compared to secondary forests and paddy fields in Kerian River Basin, Peninsular Malaysia, due to lower tree density and basal areas and less fruit availability in plantations (Azman et al. 2011).

A substantial decline of terrestrial mammal abundance in OP plantations compared to nearby forests was reported from Sabah (Wearn et al. 2017; Yue et al. 2015). Although plantations offer food resources to mammals like the Malayan sun bear (Guharajan et al. 2018), camera trap studies recorded their presence in forest patches rather than highly degraded areas such as plantations (Abidin et al. 2018). Sunda clouded leopards appear intolerant to deforestation and forest fragmentation in the Lower Kinabatangan and Kabili-Sepilok areas that are composed of small forest patches embedded with OP plantations (Hearn et al. 2018, 2019) highlighting these as priority areas requiring protection for threatened felid species (Hearn et al. 2016a; b; c).

Conversely, OP plantations hosted the highest number of carnivorous birds including striated, Chinese and Javan pond heron at Kerian River Basin, Perak due to the high availability of prey such as shrews, snakes, and rats (Azman et al. 2011). Plantations may even bring positive effects for selected species, such as the black-shouldered kite, as they provide good vantage positions, shelter from predators and a suitable physical environment for such species (Ramli and Fauzi 2018).

Human–wildlife conflict (SDG15)

Human–wildlife conflict is a main driver of species loss across the globe (Meijaard et al. 2018) usually due to illegal hunting caused by economic constraints, demand for exotic pets and products, road kills, and culling of crop pests (Azhar et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2011). Wildlife poaching is facilitated by habitat conversion to OP plantations and other agricultural crops (Azhar et al. 2013). Terrestrial animals that are highly dependent on forest, such as elephants, tend to forage in the plantations, which is perceived as raiding due to their destructive feeding habits (Guharajan et al. 2018; Cazzolla Gatti and Velichevskaya 2020). Human–elephant conflicts in plantations in the lower Kinabatangan in Sabah are driven by incidental poaching or revenge killings of elephants by plantation workers, although elephants usually actively seek to avoid humans (Evans et al. 2020). While managing elephant populations surrounding plantations via translocation to other areas appears to be an option, studies suggest that this practice is harmful to their populations. A population viability assessment of Asian elephants in the Endau Rompin landscape showed that even translocating only a few individuals poses risks on the population, suggesting the need for an in-situ management plan at OP plantations to curb human–elephant conflicts (Azhar et al. 2013; Asimopoulos 2016; Saaban et al. 2011).

Efforts to enhance benefits and mitigate adverse impacts

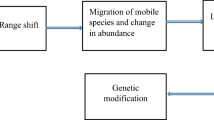

As summarized above, the impact of widespread PO production and consumption on different aspects of SDGs are undeniable (Table 1). However, to effectively expand on positive effects of PO while addressing adverse effects, there is a need to holistically evaluate different mitigation strategies and identify co-benefits and trade-offs on different SDGs. We summarize potential co-benefits and trade-offs of specific mitigation strategies in Fig. 1, proposed based on the evidence discussed below.

Proposed interaction plot of mitigation strategies and their impact on health and socioeconomics (y axis) and environment and biodiversity (x axis) SDGs. The plot suggests that several strategies may have co-benefits, and fewer strategies are either conflicting or trade-offs that detract from efforts to achieve SDGs as a whole. Co-benefit (bottom right): positive for both; one-sided benefit (bottom left or top right): positive for either; or trade-off (top left): negative for both. Level of evidence indicated by color, i.e., green: good evidence; orange: moderate evidence; and yellow: limited evidence. Grey circles indicate potentially important elements that were unable to be directly addressed in the review

Replacing palm oil with a different oil (SDG 1–3, 6–10, 12–15)

The negative perception of PO usually relates to deforestation and replacement of more diverse agricultural or agroforestry systems with these monocultures (Meijaard and Sheil 2019). However, debates about PO by supporters and opponents are often highly polarized. Calls for boycotting PO do not consider the fact that (1) OP is the highest yielding available oil crop requiring eight times less land and producing up to 20 times more oil compared to soybean, canola and sunflower (Low 2019; Woittiez et al. 2017); (2) OP crops may alleviate poverty among rural growers who may have little opportunity for other income-generation, especially in Malaysia (Sheil et al. 2009; Pirker et al. 2016); (3) economic reliance on PO in the region is widespread (Shevade and Loboda 2019); and (4) cultivation practices are heterogeneous with varying policies and enforcement practices in producer countries affecting impact (Meijaard et al. 2018). On the other hand, OP supporters often do not weigh in the losses of biodiversity and related ecosystem services but instead argue from nationalistic and socioeconomic perspectives (Liu et al. 2020).

Removing or replacing PO globally would likely adversely impact food security to producer and consumer countries (Gro Intelligence 2016) as restrictions would not only affect the demand, consequently reducing livelihood of producers, but also impact the supply of this edible oil, thus, leading to higher prices of cooking oil and consumer goods that would affect other sectors as well. A comparison of five major vegetable oil crops by Beyer et al. (2020) concluded that better management of future growing areas will be more effective at reducing environmental impacts of global vegetable oil production rather than oil crop substitution. Despite OP having larger impact on range-restricted species, OP was estimated to pose the lowest carbon and species richness loss per-ton-oil (Beyer et al. 2020). Thus, removing or replacing PO may lead to higher biodiversity losses in the future as more land needs to be converted to cultivate lower yielding oil crops leading to further habitat destruction (Meijaard et al. 2018).

Policies and regulations (SDG1,6–10,12–15)

Sustainable certification and ‘no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation’ (NDPE) policies

Generally, GHG emissions in Malaysia can be reduced by 4.1 t CO2-eq ha−1 pa simply by banning the establishment of new OP plantations on peat soil (Hashim et al. 2018). Additionally, the environmental sustainability of OP can be improved by stopping burning practices, reducing the use of peatland and swamp areas, and replacing fossil fuels by biofuel for plantation activities (Uning et al. 2020). Hence, to fulfil the growing global demand for PO while achieving conservation goals, voluntary certification under the international Roundtable Of Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) aims to ensure sustainability through a set of standards, accreditation, and process requirements (RSPO 2017; Abazue et al. 2015), encompassing optimization of productivity and efficiency while adhering to transparency, ethical, and legal principles, respecting communities, supporting smallholders, and protecting workers, while conserving the larger ecosystem.

While Malaysia is already a signatory of the RSPO network (Abazue et al. 2015), the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) certification scheme was established in 2015 to improve the PO governance and branding of Malaysian PO through nationwide sustainability initiatives, and transparency throughout the value chain (Pacheco et al. 2018). Overseen by the Malaysian Palm Oil Board (MPOB) and specifically aimed at supporting small and mid-range PO producers who cannot afford RSPO certification, the MSPO scheme has been made mandatory for OP plantations, independent smallholdings, and PO processing facilities since December 2019 (Kumaran 2019). Similar to the sustainability agenda of the RSPO that demands NDPE policies and ‘no slash-and-burn practices’ for certified plantations (Padfield et al. 2016), MSPO comprises seven governing principles, with ‘Principle 5: Environment, natural resources, biodiversity and ecosystem services’ setting the standards for mitigating impacts of OP agriculture on the biosphere.

Approximately 30% of the OP cultivated area globally is covered under voluntary or mandatory certification schemes (Kumaran 2019; RSPO 2017), and certain areas appear to be governed under multiple certification schemes (Barthel et al. 2018). Although, RSPO and MSPO ban establishment of large plantations (> 100 ha) on peatlands, this has not been enforced on the ground and slash-and-burn practices reportedly still exist (Carlson et al. 2018). Despite certification, some areas have sustained deforestation rates with major loss of tree cover and forest fires reported, and in Malaysia, the largest certified plantations have less than 1% of residual forest on their estates (Carlson et al. 2018). These reports highlight the need for routine monitoring of forest cover loss in certified plantations and penalties for members who do not comply (Carlson et al. 2018), to ensure the credibility of such certification schemes.

Although debates on the effectiveness of certification systems to mitigate forest loss and fire remain (Carlson et al. 2018), RSPO certification may reduce illegal deforestation outside of certified supply bases and act as a crucial tool to address negative impacts of PO (Heilmayr et al. 2020). However, more information is needed to determine the effect of certification on OP producers in broader areas, specifically ecological feedbacks and market forces that may improve the effect of certification. Edwards et al. (2010) proposed that funds obtained from certification of existing plantations be channeled into efforts such as biobanking and land sparing schemes that protect wildlife and forest land inside and outside of plantations. Ultimately, strict implementation of guidelines for best practices by governments and regulatory bodies, commitments to zero deforestation from all producer countries, open access of available datasets on global crop production, distribution, coverage, land cover change, and forest loss, tracking of milestones of international agreements, and legal enforcement of best practices embedded in national laws are needed to improve sustainability of PO production practices (Edwards et al. 2011).

Plantation expansion cap and high-conservation value policies

Malaysia recently committed to capping area expansion for OP plantations at 6.5 Mio ha until 2023 (Tan 2019), aiming instead to boost yield (De Pinto et al. 2017) and diversification to reduce dependency on land expansion (MPOB 2018). Besides curbing plantation expansion, high conservation value (HCV) approaches exist (often under certification schemes) to protect biological, ecological, social, or cultural values of outstanding significance, amounting to six HCV categories (HCV Resource Network 2021). HCV areas are identified at a plantation, farm or management unit level through an HCV assessment (Senior et al. 2015; Fleiss et al. 2020), which are then managed and monitored by land developers and other stakeholders. Assessment reports are publicly available and details HCVs present in specific areas as well as the evaluation results (HCV Resource Network 2021). For example, HCV detailed assessment reports for government plantations in Terengganu (Crawshaw 2019) and Sarawak (Sőzer 2016) describe at length the state of identified HCVs, such as specific mapped areas and the vegetation and wildlife species present, threats to different HCVs, and recommendations to manage the threats. While HCVs have yet to show concrete mitigatory impact in Malaysia, they may prove to be effective regulatory tools in the long term if there is commitment for transparent implementation and monitoring. Currently, although HCV assessments have been found to be beneficial, lack of monitoring indicators for plantations managers was identified as a barrier to efficient HCV implementation (Pillai 2020). Encouragingly, the Malaysian Palm Oil Green Conservation Fund (MPOGC) was incorporated on 19 February 2020 to support conservation projects such as the planting of 1 million forest trees in Lahad Datu, Sabah and the Orangutan Population Census and Pygmy Elephants program, a collaboration between the Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) and the Sabah State Government (Azian et al. 2020), which leverages on data highlighting the need to support these species in fragmented areas (Simon et al. 2019).

Biodiversity-friendly plantation management (SDG6, 13–15)

Forest corridors and riparian buffer zones

Best practice policies and the aim to achieve “biodiversity-friendly” conditions in plantations were among the top questions identified for biodiversity research (Coleman et al. 2019). Creating wildlife corridors by reserving forest patches in and around OP plantations, reforestation of underproductive OP plantation areas, and creation of forest buffer zones along rivers are necessary mitigation measures to enhance fitness of transient and vulnerable wildlife populations in OP landscapes (Wilting et al. 2012; Faruk et al. 2013; Bernard et al. 2014; Hearn et al. 2016a, b, c, 2018; Yamada et al. 2016; Holzner et al. 2019).

Riparian forests near water sources are recognized as important buffers to reduce water contamination from plantations and stabilize riverbanks (Gray et al. 2015; Luke et al. 2019), and to improve hydrology, biodiversity, ecosystem services and landscape connectivity (Marczak et al. 2010). Riparian reserve soils in Sabah release constant low rates of N2O and NO independently of soil moisture under controlled conditions in contrast to OP plantations and logged forests (Drewer et al. 2020). Streams adjacent to OP plantations with a riparian buffer in Sabah were more shaded with cooler temperature and higher quantity of leaf litter (Chellaiah and Yule 2018; Luke et al. 2017). Carbon stocks in buffers surrounded by OP plantations were similar to intact riparian areas but were highly variable depending on the survey area (Mitchell et al. 2018; Fleiss et al. 2020). Anuran diversity in plantations was enhanced by proper biodiversity management strategies such as maintenance of stream complexity, riparian buffers, and reduced use of mechanical dredging (Faruk et al. 2013), whereby the presence of buffers or patches of forest does not impact OP yield (Edwards et al. 2014).

Additionally, Bornean orangutans show behavioral flexibility and nesting behavior in certified plantation areas with available forest patches (Ancrenaz et al. 2018; Santika et al. 2019). Orangutans of all sex-age groups were found in OP plantations in Kinabatangan as these plantations constitute a source of food and shelter to build nests, as well as travel corridors (Ancrenaz et al. 2015; Sherman et al. 2020). To ensure survival of orangutans, protection of certain tree and canopy attributes of remaining forest patches is crucial due to their large size, far travel distance, and other minimal ecological requirements of these great apes (Davies et al. 2017). Conversely, tree height and canopy cover showed no significant effects for making plantations more hospitable for other (small terrestrial) mammals, but additional land sparing strategies were suggested to tackle space and resource constraints (Yue et al. 2015). Bearded pigs along the Lower Wildlife Kinabatangan Sanctuary, Sabah regularly use OP plantations as habitat although secondary forest fragments are used for a wider range of behaviors such as nesting and wallowing (Love et al. 2018). Hence, although many species can adapt to plantations, forest patches are still important for them to flourish.

Multi-/inter-cropping and soil cover crops

Intercropping of OP plantations with other crops is practiced widely in Malaysia (Corley and Tinker 2016; van Leeuwen 2019), often by smallholders to generate income in the first years of planting before the palm trees produce fruits (Ahmed et al. 2001; Hanafi et al. 2009), and if performed on peat soil, intercropping has positive effects such as protecting the soil from erosion and improving its quality. Intercropping reduces harmful pathogens, such as fungi (Woittiez et al. 2017) that spread from old to new plantations (van Leeuwen 2019) but more studies are needed to confirm the benefits of using intercropping to improve crop disease prevention, productivity, and soil quality (van Leeuwen 2019). Conversely, excessive use of fertilizers and burning of pineapple residues used for intercropping in Johor have negative impacts, but this approach could be improved by removing pineapple waste by hand (van Leeuwen 2019) and valorizing the waste as compost, feed for animals, biogas, or others (Hepton 2003; Seguí and Maupoey 2018). In Pahang, alley cropping in OP plantations facilitated habitat complexity and significantly higher arthropod beta-diversity compared to other traditional monoculture systems (Ashraf et al. 2018). Generally, arthropod orders, but not abundance or composition, were found significantly higher in polyculture than monoculture smallholdings (Ghazali et al. 2016). Planting cover crops such as legumes that form dense low-growing mats also reduces the need to use herbicides to control undergrowth (Samedani et al. 2015).

Modelling studies suggest that intercropping of OP with other crops, in particular cacao, provided high land sparing effects, while also replenishing more ground water and reducing carbon footprint (Migeon 2018; Stomph 2017; Khasanah et al. 2020). Additionally, the implementations of bio farms in Malaysia have been shown to reduce soil nutrients depletion and reduction in chemical use (Howes and Fletcher 2020). This production system improves on standard practices by extending the crop cycle, building soil organic carbon, alternative replanting methods, and minimizing soil loss (Howes and Fletcher 2020).

Biological pest control

Biological pest control agents that prey on rats such as barn owls (Salim et al. 2014; Puan et al. 2011; Saufi et al. 2020), macaques (Holzner et al. 2019), leopard cats (Silmi et al. 2013; Rajaratnam et al. 2007), or snakes and monitor lizards (Lim 1999) may decrease pesticide use and enhance biodiversity in plantations. On top of barn owls that are introduced, high density of other naturally occurring nocturnal bird species recorded in OP smallholdings also posits the potential for these carnivores to act as biological pest controls (Yahya et al. 2020). Ground and epiphytic ferns growing at OP trees constitute nesting sites for insectivorous birds (Koh 2008; Desmier de Chenon and Susanto 2005) that further act as insect pest control (Koh 2008). However, despite their adaptability to the plantations, intact forest patches adjacent to OP plantations remain necessary habitats for the biological pest control agents to rest and breed (Ruppert et al. 2018; Holzner et al. 2019).

Enhanced downstream processing (SDG1, 6–9, 13)

Output diversification

Growing a local palm-based oleochemical industry and moving the local industries up in the commodity value chain, with products spanning from base oleo like fatty acids to end products like polymer and cosmetic products (Salimon et al. 2012), has the potential to further increase the profit margin (Tong 2017), which removes reliance on further plantation expansion. Globally, about 44% of the global vegetable oil (19% from PO and palm kernel oil) was consumed in the chemical industry, with a relatively small amount devoted to biofuel production (Goh 2016). Major oleochemicals produced include fatty acids, fatty alcohols, methyl esters, glycerin, and soap noodles, with prospective markets including highly priced specialty oleochemicals like amino acid esters, and β-carotene that have important applications in the cosmetic, pharmaceutical and food industries (Mba et al. 2015). These specialty oleochemicals are also considered better substitutes for fossil-based chemicals due to their bio-based nature (Basri et al. 2013).

Additionally, there is growing interest in Europe, Japan, and Korea to import OP biomass to substitute fossil fuels for power generation (specifically as an alternative to coal for power generation and district heating in Japan and Korea) (Goh et al. 2019), second generation liquid biofuels, packaging materials as well as drop-in and novel chemicals (Sheldon 2014; Mai‐Moulin et al. 2019). Furthermore, these biomass streams can be potentially converted to building blocks (e.g., sugars) for high-value chemicals or substitutes for fossil materials (e.g., bioplastics) (Zahari et al. 2015). Two state-specific strategies were rolled out for Sabah and Sarawak, under Malaysia’s National Biomass Strategy 2020 to develop domestic high value-added biomass-based industries, through valorizing the agricultural residues in combination with municipal solid waste (AIM 2013). The plan was kickstarted with promoting energy pellet production for both local consumption and export, motivated by the Feed-in-Tariff schemes for bioenergy in both Malaysia and overseas markets (Garcia-Nunez et al. 2016).

Waste management and recovery

Waste management practices in plantations impact the air, water, and soil quality of the environment (Gaveau et al. 2014; Truckell et al. 2019). Residues produced in OP mills in Malaysia are around 100 Mio t year-1 (MPOB 2018). Two important residues are the liquid PO mill effluent (POME) and an abundant amount of low value bio-resources in the form of agricultural and forestry residues, such as empty fruit bunches (EFB) and palm kernel shell (PKS) (Truckell et al. 2019). POME disposed from PO mills contains high chemical oxygen demand and biological oxygen demand, thus, it is contained in ponds near to the mills to avoid contamination of water resources (DOE 1974, 1994; MOE 1979). Untreated POME can severely pollute water resources and release large quantities of methane, a major GHG, i.e., 1 t of POME residue can emit 33 kg of methane equivalent to 750 kg of CO2 (Rupani et al. 2010). However, treated residues composted and neutralized together with EFBs can be used as biofertilizer, whereby they can be returned to the soil to replenish carbon and nutrients through mulching to enhance soil quality in plantations (Truckell et al. 2019; Tao et al. 2017).

Discussion

Increasing recognition of the drawbacks to the rapid expansion of OP as an agricultural sector has led to efforts towards more sustainable practices to mitigate the adverse manifestations of OP industry such as deforestation and human–wildlife conflicts, human rights issues, pollution, and degradation of environmental quality (Tang and Al-Qahtani 2020).

However, perceptions surrounding PO and the OP industry are highly polarized, likely arising from the overemphasis on the negative impacts of irresponsible OP cultivation practices, an anti-PO stance from European and US governing bodies (Choiruzzad 2019; Wahab 2018), and consequently retaliatory stances from PO-producing nations (Liu et al. 2020). Even the literature appears polarized and at times directly conflicting, in particular with regards to nutritional impact of PO consumption on health and the impact of plantation management practices and certification schemes on improving sustainability.

In terms of health, a key limitation in understanding the impact of PO consumption is the fact that most studies are focused on PO as a single oil, or even if compared with other oils, they are rarely designed to observe intake as part of a wider diet. This tends to inflate both negative and positive impacts of consuming PO or its derivatives, depending on study methodology and any underlying biases (Ismail et al. 2018; Di Genova et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2015).

Conflicting views about OP agriculture and impact of sustainable management practices on the environment are often due to missing but important information at various levels making it hard for various stakeholders to understand the complex situation (Gaveau et al. 2016). There is paucity of data on awareness, adoption, and impact of sustainable practices among smallholders and, in particular, indigenous smallholders in Malaysia. Studies of land conversion of peatlands into OP plantations (Edwards et al. 2010; Gunarso et al. 2013) are through estimations or projections that often do not use the same time scale which makes them difficult to compare, highlighting the need for a universal methodological framework for more concerted monitoring of rate of conversion of peatland. Additionally, the literature and most discussions about OP agriculture are skewed towards the Indonesian context and only few studies propose mitigation efforts, especially feasible diversification of existing or rehabilitation schemes of abandoned plantations.

Existing studies aimed at enhancing sustainable practices are widely lacking in depth, long-term data, or demonstrable economic competitiveness, and thus are largely unable to provide applicable and scalable solutions. For example, while Begum et al. (2019) found that millers in Malaysia use efficient and environmentally friendly practices in waste disposal, more research is needed to understand how these practices can be further developed and adopted on a wider scale. Furthermore, the long-term impacts of diverting biomasses for industrial diversification are unclear, and due to logistic constraints, unclear business models, market uncertainties, and fluctuating CPO prices, large-scale mobilization of OP residues and POME treatment systems in rural areas has only been partially realized in the past few years. While data from specific localized studies on reducing forest fragmentation and human–wildlife conflict appear encouraging, the evidence on the broader impact of sustainable certification on improving worker conditions, smallholders and environmental conservation is still being accrued, with effective implementation and transparency being the underlying determinant.

In general, more detailed environmental and bioeconomic impact studies of sustainable vs. conventional PO production are needed to assess the benefits of (certified) sustainable management for the environment and local economy, especially for smallholders. The use of life cycle assessments may better estimate the impact of human activities on the environment, specifically for a commodity chain such as OP (Hashim et al. 2018). As many impacts of PO production on the environment are difficult to quantify, more comprehensive datasets are highly needed to develop better practices for sustainability in the long term (Hashim et al. 2018).

Many studies focus on the impact of OP as a single crop, without comparing these impacts against those arising from other existing and potential crops, which prevents a more contextualized impact assessment. For instance, coconut cultivation practices are less discussed as a driver of biodiversity loss, despite contributing to species loss in many tropical countries (Meijaard et al. 2020). Tackling biodiversity loss in plantation landscapes necessitates a deeper understanding about both positive and negative impacts of OP plantations on different species to develop solutions for environmental, wildlife and human welfare issues. In particular, there is an absence of evidence for mitigating roles of education/awareness, legal enforcement, and general reduced consumption.

Optimistically, the identified key mitigation strategies appear to possess potential co-benefits in advancing efforts for multiple SDG-related goals, with fewer strategies that either are conflicting or trade-offs that detract from efforts to achieve SDGs (Fig. 1). However, the effectiveness and longer-term impact of some mitigation efforts remain unknown.

Conclusion

In many ways, the prevailing conflicting evidence, garnered from single perspectives on this complex issue, further propagates views that are one sided. The different impacts of PO on different aspects of human and planetary health, and the corresponding SDGs, tend to be discussed separately, as are several of the solutions and mitigations efforts proposed. This situation then continues to neglect the complicated aspect of OP agriculture and agriculture in general, which consequently undermines the positive and often necessary socio-economic benefits of these industries to producer countries and the local communities (Gaveau et al. 2016). Moving forward, the varying impacts of PO on sustainability goals must be assessed with the intention to capitalize on the positive interactions and mitigate conflict of goals arising from negative interactions (Nilsson et al. 2018). Improving practices within and surrounding plantations through strategies that combine economic incentives with mitigation of adverse environmental impact may enable farmers and plantations to be part of more scalable holistic sustainable solutions.

References

Abazue CM, Er AC, Alam ASAF, Begum H (2015) Oil palm smallholders and its sustainability practices in Malaysia. Mediterr J Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n6s4p482

Abidin MZK, Mohammed AF, Nor MS (2018) Home-range and activity pattern of rehabilitated Malayan sun bears (Helarctos malayanus) in the Tembat Forest Reserve, Terengganu. AIP Conf Proc 1940(1):20036

Aguilar-León JM (2020) Understanding Anuran responses to rainforest fragmentation and oil palm agriculture in the Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary, Sabah. Doctoral dissertation, Cardiff University

Ahmad Tarmizi A (2008) Felda—a success story. Glob Oils Fats Malays Palm Oil Council 5(1):6–11

Ahmed H, Husni MHA, Anuar AR, Hanafi MM (2001) Some observations in pineapple production under different fertilizer programmes and different pineapple residue management practices. Pertanika J Trop Agric Sci 24(2):115–121

AIM (2013) Agensi Inovasi Malaysia. National Biomass Strategy 2020: New Wealth Creation for Malaysia’s Palm Oil Industry. https://www.nbs2020.gov.my/nbs2020-v20-2013. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Alam M, Siwar C, Molla R, Toriman M, Talib B (2010) Socioeconomic impacts of climatic change on paddy cultivation: an empirical investigation in Malaysia. J Knowl Glob 3(2):71–84

Amin MZM, Shaaban AJ, Ohara N, Kavvas ML, Chen ZQ et al (2016) Climate change assessment of water resources in Sabah and Sarawak, Malaysia, based on dynamically-downscaled GCM projections using a regional hydroclimate model. J Hydrol Eng 21(1):1–9

Ancrenaz M, Barton C, Riger P, Wich S (2018) Building relationships: How zoos and other partners can contribute to the conservation of wild orangutans Pongo spp. Int Zoo Yearb 52(1):164–172

Ancrenaz M, Oram F, Ambu L, Lackman I, Ahmad E et al (2015) Of Pongo, palms and perceptions: a multidisciplinary assessment of Bornean orangutans Pongo pygmaeus in an oil palm context. Oryx 49(3):465–472

Arif S, Tengku Mohd Ariff TA (2001) The case study on the Malaysian palm oil. In: UNCTAD/ESCAP regional workshop on commodity export diversification and poverty reduction in South and South-East Asia. Bangkok.

Asher C (2019) Brazil soy trade linked to widespread deforestation, carbon emissions. In: Mongabay. https://www.news.mongabay.com/2019/04/brazil-soy-trade-linked-to-widespread-deforestation-carbon-emissions/. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Ashraf M, Zulkifli R, Sanusi R, Tohiran KA, Terhem R et al (2018) Alley-cropping system can boost arthropod biodiversity and ecosystem functions in oil palm plantations. Agric Ecosyst Environ 260:19–26

Asimopoulos S (2016) Human–wildlife conflict mitigation in peninsular Malaysia. http://www.stud.epsilon.slu.se/9293/. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Asmit B, Koesrindartoto DP (2018) Identifying the entrepreneurship characteristics of the oil palm community plantation farmers in the Riau Area. Gadjah Mada Int J Bus 17(3):219–236

Aung WP, Bjertness E, Htet AS, Stigum S, Chongsuvivatwong V et al (2018) Fatty acid profiles of various vegetable oils and the association between the use of oalm oil vs. peanut oil and risk factors for non-communicable diseases in Yangon Region. Myanmar. Nutrients 10(9):1–14

Austin KG, Kasibhatla PS, Urban DL, Stolle F, Vincent J (2015) Reconciling oil palm expansion and climate change mitigation in Kalimantan, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 10(5):1–17

Awang Ali BDN, Kunjappan R, Chin M, Schoneveld G, Potter L, et al. (2011) The local impacts of oil palm expansion in Malaysia: an assessment based on a case study in Sabah State. CIFOR working paper 78. http://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Wpapers/WP-78Andriani.pdf. Accessed 14 Mar 2021

Azhar B, Lindenmayer D, Wood J, Fischer J, Manning A et al (2013) Contribution of illegal hunting, culling of pest species, road accidents and feral dogs to biodiversity loss in established oil-palm landscapes. Wildl Res 40(1):1–9

Azhar A, Osman LH, Omar ARC, Rahman MR, Ishak S (2020) Contributions and challenges of palm oil to smallholders in Malaysia. Int J Sci Res 9(6):267–273

Azian A, Kumar KS, Batumalai T (2020) Impact of Covid-19 on MPO industry In 2020—a review. https://www.mpoc.org.my/impact-of-covid-19-on-mpo-industry-in-2020-a-review/. Accessed 24 July 2021

Azman NM, Abdul Latip NS, Mohd Sah SA, Md Akil MAM, Shafie NJ et al (2011) Avian diversity and feeding guilds in a secondary forest, an oil palm plantation and a paddy field in riparian areas of the Kerian River Basin, Perak, Malaysia. Trop Life Sci Res 22(2):45–64

Barlow C (1997) Growth, structural change and plantation tree crops: The case of rubber. World Dev 25(10):1589–1607

Barthel M, Jennings S, Schreiber W, Sheane R, Royston S, et al. (2018) Study on the environmental impact of palm oil consumption and on existing sustainability standards. In: EU Publications. https://www.op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/89c7f3d8-2bf3-11e8-b5fe-01aa75ed71a1. Accessed 10 Mar 2021

Basiron Y (2011) Global market scenario impact on palm oil and other vegetable oils. In: PIPOC 2011 international palm oil congress: palm oil fortifying the world. Kuala Lumpur

Basri M, Abd Raman RNZR, Salleh AB (2013) Specialty oleochemicals from palm oil via enzymatic syntheses. J Oil Palm Res 25(1):22

Begum H, Alam ASAF, Er AC, Abdul Ghani AB (2019) Environmental sustainability practices among palm oil millers. Clean Technol Environ Pol 21(10):1979–1991

Begum RA, Raihan A, Said MNM (2020) Dynamic impacts of economic growth and forested area on carbon dioxide emissions in Malaysia. Sustainability 12:9375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229375

Bernard H, Bili R, Wearn OR, Hanya G, Ahmad AH (2014) The distribution and persistence of primate species in disturbed and converted forest landscapes in Sabah, Malaysia: preliminary results. Annu Rep pro Natura Fund 22:1–9

Beyer RM, Durán AP, Rademacher TT, Martin P, Tayleur C et al (2020) The environmental impacts of palm oil and its alternatives. Biorxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.16.951301

Bianchi AE, Da Silva AS, Biazus AH, Richards NSPS, Pellegrini LG et al (2017) Adding palm oil to the diet of sheep alters fatty acids profile on yogurt: benefits to consumers. An Acad Bras De Cienc 89(3):2471–2478

Boateng L, Ansong R, Owusu WB, Steiner-Asiedu M (2016) Coconut oil and palm oil’s role in nutrition, health and national development: a review. Ghana Med J 50(3):189–196

Bou Dib J, Krishna VV, Alamsyah Z, Qaim M (2018) Land-use change and livelihoods of non-farm households: The role of income from employment in oil palm and rubber in rural Indonesia. Land Use Policy 76:828–838

Brandi C, Cabani T, Hosang C, Schirmbeck S, Westermann L et al (2015) Sustainability standards for palm oil: challenges for smallholder certification under the RSPO. J Environ Dev 24(3):292–314

Brandon-Mong GJ, Littlefair JE, Sing KW, Lee YP, Gan HM et al (2018) Temporal changes in arthropod activity in tropical anthropogenic forests. Bull Entomol Res 108(6):792–799

Bronsky J, Campoy C, Embleton N, Fewtrell M, Fidler MN et al (2019) Palm oil and beta-palmitate in infant formula: a position paper by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 68(5):742–760

Brühl CA, Eltz T (2010) Fuelling the biodiversity crisis: species loss of ground-dwelling forest ants in oil palm plantations in Sabah, Malaysia (Borneo). Biodivers Conserv 19(2):519–529

Buckland H (2005) The oil for ape scandal: how palm oil is threatening the Orangutan. In: Friends of the Earth, London. https://www.friendsoftheearth.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/oil_for_ape_full.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Butler R (2015) Palm oil major makes deforestation-free commitment. In: Mongabay. https://www.news.mongabay.com/2015/02/palm-oil-major-makes-deforestation-free-commitment/. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Carlson KM, Heilmayr R, Gibbs HK, Noojipady P, Burns DN et al (2018) Effect of oil palm sustainability certification on deforestation and fire in Indonesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(1):121–126

Castiblanco C, Etter A, Ramirez A (2015) Impacts of oil palm expansion in Colombia: What do socioeconomic indicators show? Land Use Policy 44:31–43

Cazzolla Gatti R, Velichevskaya A (2020) Certified “sustainable” palm oil took the place of endangered Bornean and Sumatran large mammals habitat and tropical forests in the last 30 years. Sci Total Environ 742:140712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140712

CBD (2011) Aichi biodiversity target. In: Convention on biological diversity. https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/. Accessed 10 Mar 2021

Chellaiah D, Yule CM (2018) Limnologica effect of riparian management on stream morphometry and water quality in oil palm plantations in Borneo. Limnologica 69:72–80

Choiruzzad SAB (2019) Save palm oil, save the nation: palm oil companies and the shaping of Indonesia’s national interest. Asian Polit Policy 11(1):8–26

Choo YM, Muhamad H, Hashim Z, Subramaniam V, Puah CW et al (2011) Determination of GHG contributions by subsystems in the oil palm supply chain using the LCA approach. Int J Life Cycle Assess 16(7):669–681

Coleman JL, Ascher JS, Bickford D, Buchori D, Cabanban A et al (2019) Top 100 research questions for biodiversity conservation in Southeast Asia. Biol Conserv 234:211–220

Cooper HV, Evers S, Aplin P, Crout N, Dahalan MPB, Sjogersten S (2020) Greenhouse gas emissions resulting from conversion of peat swamp forest to oil palm plantation. Nat Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14298-w

Corley RHV, Tinker PB (2016) Oil palm and sustainability. In: Corley RHV, Tinker PB (eds) The oil palm. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 519–534

Cramb RA, McCarthy JF (2016) The oil palm complex: smallholders, agribusiness and the state in Indonesia and Malaysia. NUS Press, Singapore

Crawshaw J (2019) High conservation value full assessment public summary Ladang Rakyat Estate–Terengganu Collaboration between Ladang Rakyat Trengganu Sdn. Bhd., Bunge Loders Croklaan and Cargill. https://www.hcvrn.egnyte.com/dl/6MvH4PN2w0/. Accessed 16 Mar 2021

Crippa P, Castruccio S, Archer-Nicholls S et al (2016) Population exposure to hazardous air quality due to the 2015 fires in Equatorial Asia. Sci Rep 6:37074. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37074

Davies AB, Ancrenaz M, Oram F, Asner GP (2017) Canopy structure drives orangutan habitat selection in disturbed Bornean forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(31):8307–8312

De Pinto A, Wiebe K, Pacheco P (2017) Help bigger palm oil yields to save land. Nature 544:416. https://doi.org/10.1038/544416d

Desmier de Chenon R, Susanto A (2005) Ecological observations on the diurnal birds in Indonesian oil palm plantations (inventory, feeding behaviour, impact on pests). In: Proceedings of the international palm oil congress (PIPOC), pp 187–220.

Di Genova L, Cerquiglini L, Penta L, Biscarini A, Esposito S (2018) Pediatric age palm oil consumption. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(4):651

DOE (1974) Environmental quality act 1974 (Act 127) and subsidiary legislations. Department of Environment Malaysia. International Law Book Services, August 1997

DOE (1994) Classification of Malaysian rivers. Final report on development of water quality criteria and standards for Malaysia (phase IV—river classification). Department of Environment Malaysia, Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment

Dong S, Xia H, Wang F, Sun G (2017) The effect of red palm oil on vitamin A deficiency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9121281

DOSM (2020). Selected Agricultural Indicators, Malaysia, 2020. In: Department of Statistics Malaysia. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=72&bul_id=RXVKUVJ5TitHM0cwYWxlOHcxU3dKdz09&menu_id=Z0VTZGU1UHBUT1VJMFlpaXRRR0xpdz09. Accessed 20 Mar 2021

DOSM (2021) Malaysia economic performance fourth quarter 2020. In: Department of Statistics Malaysia. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=100&bul_id=Y1MyV2tPOGNsVUtnRy9SZGdRQS84QT09&menu_id=TE5CRUZCblh4ZTZMODZIbmk2aWRRQT09#. Accessed 20 Mar 2021

Drewer J, Zhao J, Leduning MM, Levy PE, Sentian J et al (2020) Linking nitrous oxide and nitric oxide fluxes to microbial communities in tropical forest soils and oil palm plantations in Malaysia in laboratory incubations. Front for Glob Change 3:4. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2020.00004

Dudgeon D, Arthington AH, Gessner MO, Kawabata ZI, Knowler DJ et al (2006) Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status, and conservation challenges. Biol Rev Cambr Philos Soc 81:163–182

Durani LW, Hamezah HS, Ibrahim NF, Yanagisawa D, Nasaruddin ML et al (2018) Tocotrienol-rich fraction of palm oil improves behavioral impairments and regulates metabolic pathways in AβPP/PS1 mice. J Alzheimer’s Dis 64(1):249–267

Edwards DP, Larsen TH, Docherty TDS, Ansell FA, Hsu WW et al (2011) Degraded lands worth protecting: the biological importance of Southeast Asia’s repeatedly logged forests. Proc R Soc B 278(1702):82–90

Edwards R, Mulligan D, Marell, L (2010) Indirect land use change from increased biofuels demand. In: European Commisson Joint Research Centre Ispra, Italy. https://doi.org/10.2788/54137. Accessed 1 Mar 2021

Edwards FA, Edwards DP, Sloan S, Hamer KC (2014) Sustainable management in crop monocultures: the impact of retaining forest on oil palm yield. PLoS ONE 9(3):e91695

Evans LJ, Goossens B, Davies AB, Reynolds G, Asner GP (2020) Natural and anthropogenic drivers of Bornean elephant movement strategies. Glob Ecol Conserv 22:e00906

Faruk A, Belabut D, Ahmad N, Knell RJ, Garner TWJ (2013) Effects of oil-palm plantations on diversity of tropical anurans. Conserv Biol 27(3):615–624

Fayle TM, Turner EC, Snaddon JL, Khen V, Chung AYC et al (2010) Oil palm expansion into rain forest greatly reduces ant biodiversity in canopy, epiphytes and leaf-litter. Basic Appl Ecol 11:337–345

Feintrenie L, Chong KW, Levang P (2010) Why do farmers prefer oil palm? Lessons learnt from Bungo District, Indonesia. Small-Scale. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-010-9122-2

Fitzherbert E, Struebig M, Morel A, Danielsen F, Bruhl C et al (2008) How will oil palm expansion affect biodiversity? Trends Ecol Evol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.012

Fleiss S, Waddell EH, Bala Ola B, Banin LF, Benedick S et al (2020) Conservation set-asides improve carbon storage and support associated plant diversity in certified sustainable oil palm plantations. Biol Conserv 248:108631

Fonseca LM, Domingues JP, Dima AM (2020) Mapping the sustainable development goals relationships. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083359

Fowler D, Nemitz E, Misztal P, Di Marco C, Skiba U et al (2011) Effects of land use on surface–atmosphere exchanges of trace gases and energy in Borneo: comparing fluxes over oil palm plantations and a rainforest. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366(1582):3196–3209

Garcia-Nunez JA, Ramirez-Contreras NE, Rodriguez DT, Silva-Lora E, Frear CS et al (2016) Evolution of palm oil mills into bio-refineries: literature review on current and potential uses of residual biomass and effluents. Resour Conserv Recycl 110:99–114

Gatto M, Wollni M, Asnawi R, Qaim M (2017) Oil palm boom, contract farming, and rural economic development: village-level evidence from Indonesia. World Dev 95:127–140

Gaveau DLA, Sloan S, Molidena E, Yaen H, Sheil D et al (2014) Four decades of forest persistence, clearance and logging on Borneo. PLoS ONE 9(7):e101654

Gaveau DLA, Sheil D, Husnayaen SMA, Arjasakusuma S et al (2016) Rapid conversions and avoided deforestation: examining four decades of industrial plantation expansion in Borneo. Sci Rep 6:1–13

Ghazali A, Asmah S, Syafiq M, Yahya MS, Aziz N et al (2016) Effects of monoculture and polyculture farming in oil palm smallholdings on terrestrial arthropod diversity. J Asia Pac Entomol 19(2):415–421

Giri S, Bhatia S (2020) Review on nutritional value and health benefits of palm oil. Res Rev Drugs Drugs Dev 2(2):9–11

Goh CS (2016) Can we get rid of palm oil? Trends Biotechnol 34:948–950

Goh CS, Aikawa T, Ahl A, Ito K, Kayo C et al (2019) Rethinking sustainable bioenergy development in Japan: decentralised system supported by local forestry biomass. Sustain Sci 15:1461–1471

Gray CL, Lewis OT, Chung AYC, Fayle TM (2015) Riparian reserves within oil palm plantations conserve logged forest leaf litter ant communities and maintain associated scavenging rates. J Appl Ecol 52(1):31–40

Gro Intelligence (2016) Palm oil: growth in Southeast Asia comes with a high price tag. https://www.gro-intelligence.com/insights/articles/palm-oil-production-and-demand. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Guharajan R, Arnold TW, Bolongon G, Dibden GH, Abram NK et al (2018) Survival strategies of a frugivore, the sun bear, in a forest-oil palm landscape. Biodivers Conserv 27(14):3657–3677

Gunarso P, Hartoyo M, Agus F, Killeen T (2013) Oil palm and land use change in Indonesia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea. Reports from the technical panels of the 2nd greenhouse gas working group of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288658092_Oil_palm_and_land_use_change_in_Indonesia_Malaysia_and_Papua_New_Guinea. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Hamada HM, Thomas BS, Tayeh B, Yahaya FM, Muthusamy K et al (2020) Use of oil palm shell as an aggregate in cement concrete: a review. Constr Build Mater 265:120357

Hamer KC, Hill JK, Benedick S, Mustaffa N, Sherratt TN et al (2003) Ecology of butterflies in natural and selectively logged forests of Northern Borneo: the importance of habitat heterogeneity. J Appl Ecol 40(1):150–162

Hamid H, Samah AA, Man N (2013) The level of perceptions toward agriculture land development programme among Orang Asli in Pahang, Malaysia. Asian Soc Sci 9(10):151–159

Hamilton RL, Trimmer M, Bradley C, Pinay G (2016) Deforestation for oil palm alters the fundamental balance of the soil N cycle. Soil Biol Biochem 95:223–232

Hanafi MM, Mohammed SM, Husni MHA, Adzemi MA (2009) Dry matter and nutrient partitioning of selected pineapple cultivars grown on mineral and tropical peat soils. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 40(21–22):3263–3280

Hansen SB, Olsen SI, Ujang Z (2014) Carbon balance impacts of land use changes related to the life cycle of Malaysian palm oil-derived biodiesel. Int J Life Cycle Assess 19(3):558–566

Hardwick SR, Toumi R, Pfeifer M, Turner EC, Nilus R et al (2015) The relationship between leaf area index and microclimate in tropical forest and oil palm plantation: forest disturbance drives changes in microclimate. Agric for Meteorol 201:187–195

Harris NL, Brown S, Hagen SC, Saatchi SS, Petrova S et al (2012) Baseline map of carbon emissions from deforestation in tropical regions. Science 336(6088):1573–1576

Hashim Z, Subramaniam V, Harun MH, Kamarudin N (2018) Carbon footprint of oil palm planted on peat in Malaysia. Int J Life Cycle Assess 23(6):1201–1217

HCV Resource Network (2021) How it works. we protect what matters most. https://www.hcvnetwork.org/how-it-works/. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Hearn AJ, Ross J, Alfred R, Samejima H, Heydon M et al (2016a) Predicted distribution of the marbled cat Pardofelis marmorata (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) on Borneo. Raffles Bull Zool 33:42–49

Hearn AJ, Ross J, Macdonald DW, Bolongon G, Cheyne SM et al (2016b) Predicted distribution of the Sunda clouded Leopard neofelis diardi (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) on Borneo. Raffles Bull Zool 33:149–156

Hearn AJ, Ross J, Macdonald DW, Hamejima S, Heydon M et al (2016c) Predicted distribution of the bay cat Catopuma badia (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) on Borneo. Raffles Bull Zool 33:165–172

Hearn AJ, Cushman SA, Goossens B, Macdonald E, Ross J et al (2018) Evaluating scenarios of landscape change for Sunda clouded leopard connectivity in a human dominated landscape. Biol Conserv 222:232–240

Hearn AJ, Ross J, Bernard H, Bakar SA, Goossens B et al (2019) Responses of Sunda clouded Leopard neofelis diardi population density to anthropogenic disturbance: refining estimates of its conservation status in Sabah. Oryx 53(4):643–653

Heilmayr R, Carlson KM, Benedict JJ (2020) Deforestation spillovers from oil palm sustainability certification. Environ Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab7f0c

Hepton A (2003) Cultural system. In: Bartholomew DP, Paull RE, Rohrbach KG (eds) The pineapple: botany, production and uses. CABI Publishing, Honolulu, pp 109–142

Hinkes C, Christoph-Schulz I (2020) No palm oil or certified sustainable palm oil? Heterogeneous consumer preferences and the role of information. Sustainability 12(18):7257. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187257