Abstract

Objective

The updated 2019 National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative vascular access guidelines recommend patient-centered, multi-disciplinary construction and regular update of an individualized end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) Life-Plan (LP) for each patient, a dramatic shift from previous recommendations and policy. The objective of this study was to examine barriers and facilitators to implementing the LP among key stakeholders.

Methods

Semi-structured individual interviews were analyzed using inductive and deductive coding. Codes were mapped to relevant domains in the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).

Results

We interviewed 34 participants: 11 patients with end-stage kidney disease, 2 care partners, and 21 clinicians who care for patients with end-stage kidney disease. In both the clinician and the patient/care partner categories, saturation (where no new themes were identified) was reached at 8 participants. We identified significant barriers and facilitators to implementation of the ESKD LP across three CFIR domains: Innovation, Outer setting, and Inner setting. Regarding the Innovation domain, patients and care partners valued the concept of shared decision-making with their care team (CFIR construct: innovation design). However, both clinicians and patients had significant concerns about the complexity of decision-making around kidney substitutes and the ability of patients to digest the overwhelming amount of information needed to effectively participate in creating the LP (innovation complexity). Clinicians expressed concerns regarding the lack of existing evidence base which limits their ability to effectively counsel patients (innovation evidence base) and the implementation costs (innovation cost). Within the Outer Setting, both clinicians and patients were concerned about performance measurement pressure under the existing “Fistula First” policies and had concerns about reimbursement (financing). In the Inner Setting, clinicians and patients stressed the lack of available resources and access to knowledge and information.

Conclusion

Given the complexity of decision-making around kidney substitutes and vascular access, our findings point to the need for implementation strategies, infrastructure development, and policy change to facilitate ESKD LP development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The management of chronic diseases is complex, affects the daily lives of people who are impacted by chronic disease, and requires attention to the individual person’s specific needs and preferences.1 In 2001, the Institute of Medicine deemed person-centered care to be one of the six pillars of quality health care.2 Person-centered care represents a shift from the traditional paradigm where the healthcare professional is the primary decision-maker towards a model that prioritizes individual wishes and requirements3. While person-centered care has been shown to result in greater satisfaction with care and patient well-being, implementation of person-centered care continues to face multiple barriers, including the challenge of shifting traditional healthcare practices and structures3.

End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) is a chronic disease that affects more than 780,000 Americans.4 In the USA, hemodialysis is the most common substitute kidney, necessitating vascular access.4 The 2006 National Kidney Foundation Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF K-DOQI) Clinical Practice Guideline for Vascular Access,5 in conjunction with “Fistula First,”6 created an environment in which kidney care professionals were all encouraged to recommend arteriovenous fistula as the ideal hemodialysis vascular access for a given patient, regardless of the patient’s individual characteristics and preferences. However, with newer data that indicates that fistula outcomes are not necessarily superior in all patient subgroups, the 2019 update of the K-DOQI Guidelines advocates for a substantial shift to a more patient-centered approach.7

To promote shared decision-making and shift towards patient-centered care, the 2019 K-DOQI guidelines emphasize the “ESKD Life Plan,” a strategy for creating a plan for all substitute kidney methods and anticipated vascular access procedures for an individual patient, for the remainder of their hemodialysis-dependent life.7 Substitute kidney methods include peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis (both in-center and home), transplant, and conservative care. Vascular access procedures include central venous catheters and arteriovenous fistulas and grafts. The Life Plan (LP) aims to maximize a patient’s options for kidney substitution and vascular access over the patient’s lifetime by planning ahead and considering contingencies. The LP is to be developed by the multidisciplinary clinician team (primary care provider, nephrologist, surgeon, interventionalist (including radiologists, nephrologists, cardiologists, and surgeons)) in conjunction with the patient. The LP represents a dramatic shift in guidelines from the “one-size-fits-all” approach of “Fistula First” in which patients were universally advised that the ideal vascular access was arteriovenous fistula. Implementing the LP may require considerable infrastructure and face significant barriers. However, little data exists regarding facility of LP implementation. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine the barriers and facilitators to LP implementation from the perspective of relevant patients and clinicians.

METHODS

Study Design

We used qualitative methods with grounded theory methodological orientation. The study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB #20–001481). Interviews were conducted by PhD-trained interviewers (KW, MSK) using video teleconferencing (Zoom, Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA) or telephone and recorded using Tape-A-Call Pro (Teltech, New York, NY). A professional transcription company (Western Consultant Services) edited the Zoom-generated transcripts for accuracy and transcribed verbatim the recorded telephone calls.

Patient Recruitment and Semi-structured Interview Guide

We recruited patients through the American Association of Kidney Patients, social media (e.g., Twitter), and the UCLA vascular surgery practice using purposeful and snowball sampling. Inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosis of advanced kidney disease (including pre-dialysis, dialysis-dependent, or with a kidney transplant) and age ≥ 18. Exclusion criteria were as follows: not English- or Spanish-speaking; inability to understand the consent process and/or give consent; or currently institutionalized. We aimed to purposefully sample patient participants of heterogeneous age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, employment, co-morbidities, experience with hemodialysis, and duration of kidney failure. We snowball sampled by asking recruited patients to recommend other patients. When a patient participant had a care partner that was highly involved in the patient’s care, available during the interview, and willing to be interviewed, the care partner was interviewed with the patient.

The patient semi-structured interview guide (SSIG) items were based on a previously used SSIG for a project focused on vascular access decision-making 3and refined to address preferences and attitudes about educational materials to support the vascular access decision-making process, engagement in constructing the ESKD LP, and partnering with clinicians and individuals involved in the decision-making process (Appendix 1). When patient participants were not familiar with the LP, the concept was explained by the interviewer and the LP form was shown to the participant. Throughout the course of interviewing and concurrent analysis, the SSIG was refined to further explore codes that investigators thought could contribute to potential themes.

Clinician Recruitment and Semi-structured Interview Guide

Similarly, we recruited clinicians through the investigators’ professional networks and social media using purposeful and snowball sampling. We aimed to purposefully sample clinicians from different specialties, practice settings, geographic diversity, gender, and years in practice. US clinicians were eligible if they were currently caring for patients with kidney disease. We aimed to recruit four pre-planned groups of individual clinicians specified by the LP (primary care, interventional radiology, nephrology, surgery) and included other clinicians (e.g., nurses and coordinators) as we pursued certain lines of inquiry.

Clinician SSIG items focused on preferences and attitudes about the needed LP’s multidisciplinary execution, patient involvement, and clinical management of vascular access. We based the clinician SSIG on published barriers/facilitators of multidisciplinary teams, and the investigators’ extensive clinical experience in interacting with the specialty clinicians8 (Appendix 2). As above, the SSIG was refined throughout the interview and analysis process. Similarly, when clinician participants were not familiar with the LP, the interviewer explained the LP.

Coding and Analysis

We analyzed patient and clinician interviews separately using inductive and deductive coding and Dedoose v9.0.54, a platform for organizing and analyzing research data (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Manhattan Beach, CA).9 Following Charmaz’s methodology, we used Dedoose to manually code and analyze transcripts as interviews were conducted.9,10,11 We created initial codes consisting of a short phrase generated by the investigator directly from the data with line-by-line coding.9,10,11 Codes were process codes using gerunds (“-ing” words) to describe participant action in the data.12 Initially, each interview transcript was independently coded by two investigators (KW, MSK). Investigators reviewed the double-coded transcripts and discussed coding discrepancies during bi-weekly investigator meetings until consensus.

When 6 interviews were coded in each participant category, the investigators observed, through constant comparison, repeated concepts in the data. Two investigators (KW, MSK) independently grouped the initial codes into focused codes (constructs that succinctly capture important pattern in the data in relation to the research question and are more conceptual in nature.)9,10,11 The larger investigator group reached consensus on the final list of focused codes. We applied the focused codes to the remaining transcripts, with KW and MSK checking to ensure consistency between coders. This first part of the coding process was inductive.

We then used deductive methods and mapped focused codes specific to LP implementation to relevant domains in the 2009 Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), then subsequently updated to the 2022 CFIR.13,14 The CFIR is a comprehensive framework that provides a structure for describing factors critical to the implementation of an innovation. The domains include (1) Innovation, which describes the degree to which the innovation is cost-effective, evidence-based, easy or complex to implement, and advantageous to implement; (2) Outer Setting, or the larger context in which the intervention is being implemented, which may include local, regional, and national contextual factors; (3) the Inner Setting, or the context of the organization in which the innovation is being implemented; (4) the Individuals, or the roles and characteristics of the individuals implementing the intervention; (5) and the Implementation Process, or the activities and strategies used to implement the innovation. Not all domains or constructs with a domain may be relevant to particular innovation implementation. We used constant comparison to analyze the data with techniques including examining negative cases (e.g., participants who had perceptions that contrasted significantly from others); contrasting perceptions and views from participants in different settings or specialties; contrasting patient and clinician perspectives; and examining emotions, language, and use of metaphors/similes. 10,11,13,15,16 (Further details regarding consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative (COREQ) studies available in Appendix 3).17

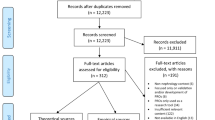

RESULTS

We interviewed 21 clinicians, 11 patients and 2 care partners between 4/2021 and 6/2022 (Table 1). Interviews lasted 40–60 min. During analysis, we looked for any indication that clinician participants from a particular specialty expressed unique experiences or concerns and whether there were discrepancies among participants within a specialty that would require further exploration and found none. Very few clinicians and no patient participants had pre-existing knowledge of the LP. We identified barriers and facilitators across three 2022 CFIR domains: Innovation, Outer Setting, and Inner Setting. Within each domain, we categorized barriers/facilitators into CFIR constructs (italicized below), although we note that some findings fit into multiple CFIR constructs.

Domain: Innovation

The “Innovation” domain refers to the intervention being implemented. Clinicians cited concerns about the evidence basis for LP construction, relevant to the CFIR construct innovation evidence base. Clinicians of various specialties noted lack of evidence to make vascular access decisions based on comorbidities, age, and other clinical and patient characteristics. One nephrologist expressed a desire for a clinical calculator or decision-aid that would assist with the vascular access decision-making process. Further, nephrologists noted the challenges of determining both the timing of initiation of substitute kidney and vascular access. Nephrologists repeatedly referred to the variable rate of ESKD progression, lack of reliable prediction tools in this area, and reluctance to initiate conversations too early, which could cause undue emotional distress for patients (Representative quotes in Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Both clinicians and patients had significant concerns about the complexity of decision-making around substitute kidney and patients’ ability to digest the overwhelming amount of information and clinical terms needed to effectively participate in LP creation (innovation complexity). Clinicians noted that patients were often shocked and knew little about kidney failure when they were diagnosed, making advanced planning difficult. Beyond the initial diagnosis, the decision-making associated with setbacks was emotionally fraught. Moreover, clinicians perceived that often patients were reluctant to engage in complex shared decision-making and preferred to be told what to do in difficult situations.

Clinicians identified a variety of factors related to the innovation complexity of logistics surrounding LP implementation, including how the LP would be updated, who would be responsible for keeping it updated, how it would be shared across healthcare systems with different electronic health records (EHR), and the ability to assemble a multi-disciplinary team to discuss the LP (available resources). Clinicians cited language and cultural barriers as adding to the complexity of LP implementation, and that establishing rapport takes longer when these barriers exist.

Patients voiced similar concerns about the innovation complexity. When initially facing kidney substitution, patients recalled feeling “shocked,” “scared,” and so overwhelmed with that it was difficult to understand new information. While patients described slowly absorbing information over time, they described challenges dealing with setbacks and repeatedly having to make major decisions. The concept of planning ahead for major health decisions seemed daunting. Patients and care partners described a preference to manage only one decision at a time—the most imminent and necessary decision. Patients stressed that creating the LP might require repeated conversations over a long period of time, and many patients are likely not ready to have these difficult conversations, particularly when first diagnosed with kidney failure. However, a small minority of patients believed preparing patients for the future could possibly jolt patients into taking action. Patients’ beliefs about the complexity of the intervention also overlaps with the Outer Setting concept local attitudes, or the sociocultural values and beliefs that support or do not support implementation.

Clinicians and patients praised the relatively simple nature of the LP, relevant to innovation design. Clinicians embraced planning for subsequent accesses and documenting the plan to record patient preferences and facilitate communication between clinicians, particularly between institutions. Clinicians also supported detailing the patient’s clinical team members in the LP, enabling appropriate clinician communication.

Patients and care partners liked the personalized nature of the LP, contrasting it to existing brochures/pamphlets, but identified several areas where innovation design could be improved. Patients noted that some words in the current LP such as “modality” would need to be translated to more patient-friendly language. Others noted that the LP should be in a large text for patients with vision issues. One patient expressed concern that the linear structure of the existing ESKD LP suggests that patients could not go back to a previous decision or approach and suggested making the LP diagram a circle.

Clinicians, particularly those in private practice, worried about the innovation cost of LP implementation, without a reimbursement mechanism for the required effort, a concept which also falls into the Outer Setting CFIR construct of financing. One of the LP tenets is multi-disciplinary shared decision-making. This struck clinicians as extremely complex and potentially very costly to implement. In some academic practices, multi-disciplinary meetings are an existing element of the culture and are considered a routine component of employment. However, this is rare in private practice.

Domain: Outer Setting

The “Outer Setting” of the intervention refers to the larger context in which the intervention is being implemented. This may include the local, regional, and national context. Relevant to Iocal attitudes, overwhelmingly, patients felt as though they were underestimated by the healthcare system, their preferences not valued, and they were largely uninformed about potential setbacks, such as kidney transplant failures, fistula failures, and peritonitis. Patients described not being offered modality choices, such as home-hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, and learning about these options months or years later from other patients, internet searches, or patient advocacy associations. Several non-White patients also noted that non-White patients were less likely to be offered these options; they perceived that clinicians made assumptions about their lack of ability to implement these modalities. Patients questioned whether financial incentives from dialysis facilities were responsible for the lack of choices and suspected that dialysis facilities profited more with in-center hemodialysis (local conditions).

Pertinent to policies and laws and performance measurement pressure, clinicians noted that current Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ESKD Quality Incentive Program (QIP) policies18 are likely to impede clinicians’ autonomy to implement personalized patient care. Relatedly, patients reported being pressured by facility staff to transition from a catheter to a fistula. While the majority of clinician participants praised the move away from the “fistula-first” approach and towards a more personalized decision-making approach, a select few still strongly believed in “fistula-first” and reported that they did not offer patients many choices. Clinicians noted that there were currently no policies that would offer reimbursement or incentive programs which would facilitate implementation of the LP (financing). While several noted that reimbursement policies aligning with the LP would improve adoption, others noted that the time and effort would not be worth a small reimbursement.

Domain: Inner Setting

The “Inner Setting” refers to the setting where the implementation of the intervention is taking place. In this case, we used the term “Inner Setting” to describe the practice settings in which the ESKD LP would be implemented. Clinician participants described a variety of practice settings, including academic, private, hospital-employed, and Veterans Affairs facilities that reflected varied structural characteristics and relational connections, which could influence LP implementation. Clinicians practicing in larger organizations such as academic medical centers with nephrology clinics, interventional radiology, a dialysis facility, and vascular access surgeons within the same institution usually have a shared EHR. Clinicians noted this structure could facilitate implementation through communication via case conferences, sharing the LP across the EHR, and shared organizational LP rollout. Larger institutions may also have more resources to implement new programs. However, several clinicians noted that in their experience, large academic centers with many types of specialists and sub-specialists resulted in less continuity of care per provider and looser networks between clinicians, which was detrimental for patients.

Private practice community clinicians confirmed these sentiments, describing how their reliance on referrals fostered close working relationships with other clinician groups, which facilitated communication and strengthened ties between clinicians. However, challenges in structural characteristics in the private practice setting included significant pressures to see many patients and fewer resources to implement new programs including the LP.

Regarding implementation climate, patients and clinicians described significant tension for change. Both compared the relative advantage of the LP to the status quo, where little advanced planning occurs and decisions are made impromptu. Numerous clinicians had experienced cases where emergency-based decision-making led to poor patient outcomes. Patients described receiving little information from clinicians about kidney disease and their treatment options. Patients who worked with other patients, either in advocacy or patient education roles, emphasized the critical need to educate patients on different options, future decisions, and potential setbacks.

Clinicians were divided on the compatibility of the LP with their current practice. Some strongly believed in aligning decisions with patient values and reported already integrating shared decision-making into their practice. These clinicians already felt that it was critical to always consider the next access. Others questioned whether the effort and coordination required to create the LP would fit into current workflows. Some believed patients desire a more prescriptive approach over shared decision-making. Moreover, several clinicians felt that anatomy and other patient-specific clinical factors were major drivers in access decision-making, making it difficult to give patients choice. Patients embraced the opportunity to discuss their values with their care team and welcomed regular discussions about current values and preferences.

Clinicians and patients stressed the lack of available resources and access to knowledge and information. Limits on clinician time and availability severely restricts access to necessary time to implement the LP, including time with patients, documenting, and communicating with the other multi-disciplinary team clinicians. Patients repeatedly conveyed that they already experienced rushed visits with clinicians of all types and specialties. Numerous clinicians reported that their health care organizations already had limited numbers of staff, who were stretched to the limit. Further increasing the challenge would be the amount of training that would be needed to train all involved staff on the LP. Finally, clinicians noted that there are no existing resources or infrastructure to support the required constant LP updates at all of a patient’s healthcare delivery sites.

DISCUSSION

This study elucidated barriers and facilitators to LP implementation by applying CFIR to patient and clinician perspectives. Patients and clinicians shared the view that the LP addressed important issues of lack of planning that often occurs with vascular access, lack of information that patients receive, and need to individualize care planning for patients with ESKD.

Clinicians raised significant concerns about lack of reliable evidence to inform timing of kidney substitute initiation and vascular access decision-making. One of the lead authors of the 2019 KDOQI guidelines has indicated that the currently quality of the evidence relevant to the access surgeon is limited.19 Similarly, despite numerous efforts to create prediction models for the timing of initiation of chronic kidney substitution, this task remains a significant challenge for clinicians to accomplish with any accuracy.20 Further, individualizing recommendations is difficult when little reliable evidence exists regarding variation in outcomes by specific patient characteristics. As several clinicians noted, age and frailty are often a primary consideration in making vascular access recommendations given frailty is associated with adverse treatment outcomes for ESKD with respect to kidney transplant21 and dialysis22 and is associated with increased risk of mortality.23 However, little data exists as to the association of frailty and vascular access outcomes.24

Both clinician and patient participants expressed concern about the ability of patients to comprehend and digest information required to adequately participate in the shared decision-making process around modality and vascular access planning. Other authors have demonstrated that pre-operatively, as little as 14% of patients are adequately “informed” about dialysis vascular access creation.25 Our previous qualitative work also found that patients lacked clear understanding about the types of access options and potential downstream consequences.26

Further contributing to the challenge of successful shared decision-making is the intense phenomenon of emotional overwhelm emphasized by both clinician and patient participants. “Emotional overwhelm” relates to “the emotional burden of the illness experience and consequent cognitive overload” and is distinct from “information overload,” which refers to “complexity, uncertainty, or volume of information involved in the decision.”27 Feeling both is common in patient experiences where the diagnosis and/or treatment may be life-changing, such as cancer or diabetes.28,29 Anxiety and other strong negative emotions can impair decision-making and increase passivity.30,31 Clinicians may need to address these emotions before proceeding with the decision-making process to mitigate lack of patient comprehension and engagement.

In our previous work, we found that as patients gain more experience with kidney substitution and with vascular access, their concerns and preferences shift towards issues specific to their individual experiences26. In an effort to provide a surrogate for experience to patients who are earlier in the kidney substitution journey, education and exposure to other patients’ experiences may assist with engaging patients in LP development. Similarly, it is critical that the LP be revised on a regular basis as a patient’s preferences and needs will likely change as they progress through the kidney substitution journey.

The commonly experienced emotional overwhelm in the ESKD population further raises the important issue of adequate emotional and psychological support. Dialysis-dependent patients report feeling bound to dialysis, feeling underrecognized and ignored with respect to mental health support, worrying about an uncertain future, developing self-reliance, and responding to a major lifestyle overhaul.32 Roughly 50% of patients with ESKD rely on dialysis experience symptoms of depression and anxiety.33 Approximately 27% of US adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have mental illness, and 7.1% have serious mental illness.34 Despite evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of psychological treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise and relaxation techniques in treating depression in dialysis-dependent patients,35 few ESKD patients with severe mental health symptoms receive behavioral health treatment.36 An important component of LP implementation will be strategies to ensure patients with CKD/ESKD who need mental health services get the necessary care. Significant economic incentive and policy barriers exist to LP implementation. As was oft-noted by clinicians in our sample, the CMS “Fistula First-Catheter Last” initiative and ESKD QIP remain unchanged.37 Both clinician and patient participants noted a strong push from dialysis facilities to promote fistulas, reflecting the current policy incentives. Moreover, clinician participants noted the lack of reimbursement for implementing the LP and no healthcare institution or practice can remain functional without a positive financial balance. As long as these financial incentives and penalties exist, without adequate financial reimbursement for implementing the LP, there will be a conflict between guidelines and practice. A policy overhaul that prioritizes patient-centric care is critically needed to ensure adequate guideline implementation.

Importantly, our study identified a significant lack of knowledge of the LP among patients and clinicians. As participants emphasized, LP implementation will require significant clinician and staff training and processes for storing and sharing the document. Similar challenges were encountered in implementation of Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) forms, leading to the development of POLST registries which could be integrated into health care systems’ EHRs.38,39 A similar approach may be useful for the LP and will require state level or ideally, national efforts to realize.

A major strength of our study was the wide range of clinician specialties, locations, and practice settings. Additionally, we included patient participant perspectives which is often excluded from implementation studies. By including a broad range of clinician specialties and settings across the USA and patient perspectives, we have broadened the transferability of the study, an important concept in qualitative research that describes how the study’s findings could be applicable to other contexts, times, and populations. Limitations include the lack of interviews with operational managers, institutional executives, and payers who will need to play a significant role in the successful implementation of the LP. All interviews were conducted in English; while we had interviewers available who could have conducted the interview in Spanish, we did not recruit any participants who spoke Spanish exclusively. Future work will include efforts to involve non-English speakers.

CONCLUSION

Patients and clinicians in our study support a tension for change from the status quo, but few large-scale organizational resources or efforts currently exist to implement the ESKD LP. From the clinician perspective, lack of effective, early planning puts patients at increased risk for limited access options in the future. From the patient perspective, there is a critical need for improved comprehensive education regarding kidney substitution and vascular access options and their potential complications. In order for large-scale implementation of the LP to occur, significant organizational change needs to occur, including resources for training clinicians on how to effectively communicate the goals of the LP with patients, processes to update, store, and access the LP, and means of sharing the LP across health systems and practices.

References

Michielsen L, Bischoff E, Schermer T, Laurant M. Primary healthcare competencies needed in the management of person-centred integrated care for chronic illness and multimorbidity: Results of a scoping review. BMC Prim Care. 2023;24(1):98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02050-4.

Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. 2001.

American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Person-Centered C. Person-Centered Care: A Definition and Essential Elements. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):15-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13866.

United States Renal Data System. 2022 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. 2022. https://adr.usrds.org/2022. Accessed 28 June 2023.

Vascular Access Work G. Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48 Suppl 1:S248-73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.040.

Neumann ME. "Fistula first" initiative pushes for new standards in access care. Nephrol News Issues. 2004;18(9):43, 47-8.

Lok CE, Huber TS, Lee T, et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for vascular access: 2019 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(4):S1-S164.

Soukup T, Lamb BW, Arora S, Darzi A, Sevdalis N, Green JS. Successful strategies in implementing a multidisciplinary team working in the care of patients with cancer: an overview and synthesis of the available literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:49-61. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.S117945.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage; 2006.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Second edition. Sage; 2014.

Carmichael T, Cunningham N. Theoretical Data Collection and Data Analysis with Gerunds in a Constructivist Grounded Theory Study. Electron J Bus Res Methods. 2017;15:59.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0.

Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage; 2014.

Corbin J, Strauss AC. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications, Inc.; 2008.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357.

Fishbane S, Miller I, Wagner JD, Masani NN. Changes to the end-stage renal disease quality incentive program. Kidney Int. 2012;81(12):1167-1171.

Huber TS, Buhler AG, Seeger JM. Evidence-based data for the hemodialysis access surgeon. Semin Dial. 2004;17(3):217-23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17309.x.

Lopez-Martinez D, Chen C, Chen M-J. Machine learning for dynamically predicting the onset of renal replacement therapy in chronic kidney disease patients using claims data. Springer; 18–28.

Alsaad R, Chen X, McAdams-DeMarco M. The clinical application of frailty in nephrology and transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2021;30(6):593-599. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/mnh.0000000000000743.

Sy J, Johansen KL. The impact of frailty on outcomes in dialysis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26(6):537-542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/mnh.0000000000000364.

Alfaadhel TA, Soroka SD, Kiberd BA, Landry D, Moorhouse P, Tennankore KK. Frailty and mortality in dialysis: evaluation of a clinical frailty scale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(5):832-40. doi:https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.07760814.

Woo K, Gascue L, Norris K, Lin E. Patient frailty and functional use of hemodialysis vascular access: a retrospective study of the US Renal Data System. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;80(1):30-45.

Ruske J, Sharma G, Makie K, et al. Patient comprehension necessary for informed consent for vascular procedures is poor and related to frailty. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73(4):1422-1428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.06.131.

Woo K, Pieters H. The patient experience of hemodialysis vascular access decision-making. J Vasc Access. 2021;22(6):911-919. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1129729820968400.

Bester J, Cole CM, Kodish E. The Limits of Informed Consent for an Overwhelmed Patient: Clinicians' Role in Protecting Patients and Preventing Overwhelm. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(9):869-86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.9.peer2-1609.

McCloskey L, Sherman ML, St. John M, et al. Navigating a ‘Perfect Storm’ on the Path to Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus After Gestational Diabetes: Lessons from Patient and Provider Narratives. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23(5):603-612. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2649-0.

Houldin AD, Lewis FM. Salvaging their normal lives: a qualitative study of patients with recently diagnosed advanced colorectal cancer.

Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Passive decision-making preference is associated with anxiety and depression in relatives of patients in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2009;24(2):249-254.

LeBlanc VR, McConnell MM, Monteiro SD. Predictable chaos: a review of the effects of emotions on attention, memory and decision making. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2015;20(1):265-282.

Nataatmadja M, Evangelidis N, Manera KE, et al. Perspectives on mental health among patients receiving dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;36(7):1317-1325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa346.

Rebollo Rubio A, Morales Asencio JM, Eugenia Pons Raventos M. Depression, anxiety and health-related quality of life amongst patients who are starting dialysis treatment. J Ren Care. 2017;43(2):73-82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jorc.12195.

Wilk AS, Hu J-C, Chehal P, Yarbrough CR, Ji X, Cummings JR. National Estimates of Mental Health Needs Among Adults With Self-Reported CKD in the United States. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7(7):1630-1642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2022.04.088.

Natale P, Palmer SC, Ruospo M, Saglimbene VM, Rabindranath KS, Strippoli GFM. Psychosocial interventions for preventing and treating depression in dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004542.pub3.

Watnick S, Kirwin P, Mahnensmith R, Concato J. The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(1):105-110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/ajkd.2003.50029.

Lee T. Fistula first initiative: historical impact on vascular access practice patterns and influence on future vascular access care. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2017;8(3):244-254.

Zive DM, Schmidt TA. Pathways to POLST registry development: Lessons learned. Portland, OR: Center for Ethics in Health Care Oregon Health & Science University. 2012.

Schmidt TA, Zive D, Fromme EK, Cook JNB, Tolle SW. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): lessons learned from analysis of the Oregon POLST Registry. Resuscitation. 2014;85(4):480-485.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R03DK127131 [KW] and 1K01AG076865 [MK]). The National Institutes of Health did not participate in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. KE is a consultant for Acumen LLC, Burlingame CA and Boehringer Ingelheim and receives payment from Dialysis Clinics, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest:

The remaining authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. All authors had access to the data and had a role in writing the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keller, M.S., Mavilian, C., Altom, K.L. et al. Barriers to Implementing the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative End-Stage Kidney Disease Life Plan Guideline. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 3198–3208 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08290-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08290-5