Abstract

Background

Black individuals have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). However, it remains unclear whether there are any biological factors that predispose Black patients to COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality.

Objective

To compare in-hospital morbidity, mortality, and inflammatory marker levels between Black and White hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Design and Participants

This single-center retrospective cohort study analyzed data for Black and White patients aged ≥18 years hospitalized with a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test between March 1, 2020, and August 4, 2020.

Main Measures

The exposure was self-identified race documented in the medical record. The primary outcome of was in-hospital death. Secondary outcomes included intensive care unit admission, hospital morbidities, and inflammatory marker levels.

Key Results

A total of 1,424 Black and White patients were identified. The mean ± SD age was 56.1 ± 17.4 years, and 663 (44.5%) were female. There were 683 (48.0%) Black and 741 (52.0%) White patients. In the univariate analysis, Black patients had longer hospital stays (8.1 ± 10.2 vs. 6.7 ± 8.3 days, p = 0.011) and tended to have higher rates of in-hospital death (11.0% vs. 7.3%), myocardial infarction (6.9% vs. 4.5%), pulmonary embolism (PE; 5.0% vs. 2.3%), and acute kidney injury (AKI; 39.4% vs. 23.1%) than White patients (p <0.05). However, after adjusting for potential confounders, only PE (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.07, 95% CI, 1.13–3.79) and AKI (aOR 2.16, 95% CI, 1.57–2.97) were statistically significantly associated with Black race. In comparison with White patients, Black patients had statistically significantly higher peak plasma D-dimer (standardized β = 0.10), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (standardized β = 0.13), ferritin (standardized β = 0.09), and lactate dehydrogenase (standardized β = 0.11), after adjusting for potential confounders (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Black hospitalized COVID-19 patients had increased risks of developing PE and AKI and higher inflammatory marker levels compared with White patients. This observation may be explained by differences in the prevalence and severity of underlying comorbidities and other unmeasured biologic risk factors between Black and White patients. Future research is needed to investigate the mechanism of these observed differences in outcomes of severe COVID-19 infection in Black versus White patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Racial disparities in health have been recognized in the USA for decades and are a major public health concern.1 Black individuals are more likely than White individuals to have major chronic diseases, including metabolic disorders, kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, cancers, mental illnesses, and pregnancy complications among others.2,3,4,5 This results in higher risks of morbidity and mortality. According to data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), non-Hispanic Black individuals had an approximately 2 times higher risk of all-cause mortality, 1.2 times higher risk of cardiovascular mortality, and 1.4 times neoplasm-related mortality6 than White individuals. Black individuals in the USA also have a threefold risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) compared to White individuals and are more likely to have albuminuria.5,7 These differences may be explained by differences in genetics, socioeconomic status, access to care, diet, culture, and other factors and the interplay between these factors.6,8

Since the emergence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), racial disparities in the development, severity, and outcomes of this disease have become increasingly apparent.9,10,11 It has been reported that Black individuals have been disproportionately affected by the novel virus.12,13,14,15,16 For example, approximately three times the rate of infection and six times the rate of death were observed in counties in the USA where a large percentage of Black individuals live compared with those where a large percentage of White individuals live.13 Furthermore, according to the report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in November 2020, the Black population had a 1.4 times higher number of COVID-19 patients, 3.7 times higher rate of COVID-19 hospitalization, and 2.8 times higher COVID-19 mortality rate than White, non-Hispanic populations.14

The unequal magnitude of disease burden in the Black population is thought to be driven by higher rates of comorbidities and increased viral exposure among the Black population, which is due primarily to differences in social determinants of health.15 These include more limited health care access, higher rates of disadvantageous housing conditions, higher incarceration rates, and greater exposure to long-term care residence.17 However, it remains unclear whether there are any genetic or biological factors that predispose Black individuals to COVID-related morbidity and mortality, since some studies have demonstrated that once infected and hospitalized, there was no racial difference in mortality rates after controlling for age, sex, and underlying comorbidities.18,19

Using information from the electronic medical record at the Boston University Medical Campus, we aimed to investigate whether there were differences in outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients who self-identified as Black or White. Additionally, we aimed to identify biological and other determinants of outcomes in self-identified Black and White individuals hospitalized with COVID-19.

METHODS

Study Population

This is a retrospective chart review, cohort study in adult Black and White COVID-19 patients aged ≥18 years old who were hospitalized at Boston Medical Center (BMC) between March 1, 2020, and August 4, 2020. This inner-city safety net hospital is an ideal setting to perform such an evaluation as it consists of comparable numbers of Black and White patients hospitalized with COVID-19 with relatively similar socioeconomic backgrounds. All patients included in this study tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing. The study protocol was approved by the Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board (H-40341)

Study Measurements

Characteristics of patients were extracted from the BMC hospital database (electronic medical record). The following patient baseline characteristics were extracted: age, sex, self-identified race, health coverage status (commercial insurance, public insurance, and uninsured), last body mass index determination (BMI), smoking history, and alcohol use. Using data form the US Census Bureau, zip code of each patient was linked with the estimated median household income in 2019 for each zip code.20 We also recorded presence of underlying comorbidities using data from the physician diagnosis of underlying medical conditions determined by the International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) in the electronic medical record. These include type 2 diabetes mellitus (E11), hypertension (I10), dyslipidemia (E78), heart disease (coronary artery disease, I25, or heart failure, I50), cerebrovascular disease (I66, I67, I69, G45), asthma (J45), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, J44), CKD, end-stage renal disease (ESRD, N18.6), proteinuria (R80), malignancy (C80), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (B20). The most recent hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) and outpatient blood pressure measured prior to admission were recorded to reflect control of diabetes and hypertension, respectively. The latest clinic estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) measured prior to hospitalization was recorded to reflect baseline kidney function. Furthermore, we recorded in-hospital medical therapy for COVID-19, including corticosteroids, interleukin-6 antibodies, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, and remdesivir.

Inflammatory marker levels measured at the time of hospitalization or as soon thereafter as was available (within 3 days after admission) were extracted from the hospital EMR. These included plasma D-dimer, plasma C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), plasma ferritin and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), absolute lymphocyte count, and absolute neutrophil count. Since inflammatory markers often change over time in acute COVID-19 infection, we also recorded and analyzed highest levels of D-dimer, ESR, CRP, ferritin, LDH, and absolute neutrophil count and lowest level of absolute lymphocyte count with the aim to minimize the confounding effect of timing of presentation. Oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry at the time at the time of hospitalization was also collected.

The primary outcome of this study was in-hospital death. Secondary outcomes included intensive care unit (ICU) admission, need for intubation, hospital length of stay, hypoxemia (O2 saturation <90%), and diagnosis based on the ICD-10-CM codes of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS, J80), myocardial infarction (I21), acute kidney injury (AKI, N17), severe sepsis/septic shock (R65.20, R65.21), deep venous thrombosis (I82.40), pulmonary embolism (PE, I26), and inflammatory marker levels. All hospital outcomes were derived from admission diagnosis extracted from the EMR and were validated by manual chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as arithmetic means with standard deviation (SD) or standard error of mean (SEM). Categorical variables were reported as number of patients with percentages. Comparison of baseline characteristics and laboratory measurements between Black and White patients was performed using independent sample t-test for continuous parametric data, Mann-Whitney U test for continuous non-parametric data, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) that represent the association between race and outcomes with White race as the reference; multivariable models to assess predictors of inflammatory markers were also conducted. Initially, variables were subjected to univariate analysis. Covariates with a p-value of <0.2 and those with plausible biologic or behavioral relationships or previously documented to be related with the outcomes of COVID-19 were included into the model. Then, backward elimination was performed to remove insignificant variables from the models. Linear regression was applied to determine the correlation between race and inflammatory marker levels with White race as the reference group. Due to the concern of multiple testing of clinical outcomes, we define true statistical significance as the p-value of <0.01, while the p-value of <0.05 was defined as having a trend towards statistical significance. SPSS version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to perform all statistical analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 1,478 adult hospitalized COVID-19 patients were identified from the hospital EMR between March 1, 2020, and August 4, 2020. Among them, 8 Asian patients, 18 patients of other races, and 28 patients with unavailable data on race were excluded. Finally, 1,424 Black and White patients were included in the analysis. The mean ± SD age was 56.1 ± 17.4 years and 663 (44.5%) were female (Table 1). Overall, there were 683 (48.0%) Black and 741 (52.0%) White patients. Compared to White patients, Black patients were statistically significantly older (59.5 ± 17.1 vs. 52.9 ± 17.0 years, p <0.001) and had higher rates of presence of underlying comorbidities, uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension, and receipt of chronic medications (Supplemental Table 1), and had lower baseline eGFR (79.5 ± 36.0 vs. 83.7 ± 28.8 mL/min/1.73m2, p = 0.010). In addition, a significantly lower percentage of Black patients were treated with remdesivir (3.2% vs. 6.2%, p = 0.008). In terms of the socioeconomic status, the distributions of health coverage types were similar between Black and White patients (commercial insurance: 17.7% vs. 16.2%; public insurance: 80.2% vs. 81.2%; uninsured: 1.6% vs. 1.9%, p = 0.747). We found that the estimated income based on zip code was slightly lower in Black patients compared with White patients (median: $58,105 vs. $60,579 per household in 2019, p <0.001).

Clinical Outcomes

In the univariate analyses, Black patients tended to have higher rates of in-hospital death (11.0% vs. 7.3%, p = 0.012) and myocardial infarction (6.9% vs. 4.5%, p = 0.047), and had statistically significantly higher rates of PE (5.0% vs. 2.3%, p = 0.006) and AKI (39.4% vs. 23.1%, p <0.001) than White patients (Table 2). In addition, Black patients tended to have longer hospital stays than White patients (mean ± SD: 8.1 ± 10.2 vs. 6.7 ± 8.3 days, p = 0.011).

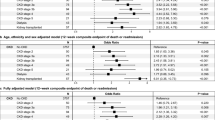

In multivariable models, Black patients had a statistically significantly higher odds of PE than White patients (aOR 2.07, 95% CI, 1.13–3.79; Fig. 1) after adjusting for age, sex, and presence of underlying CKD. In addition, after excluding 67 patients with pre-existing ESRD from the analysis, Black patients had a statistically significantly higher odds of AKI (aOR 2.16, 95% CI, 1.57–2.97) after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and presence of underlying type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and baseline eGFR. No statistically significant independent association between race and other hospital outcomes was observed. Effect estimates of variables included in the multivariable models are shown in the Supplementary Table.

Adjusted association between race and outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit. Variables adjusted for in multivariate analysis were shown in the Supplemental Table 2. Patients with pre-existing ESRD were excluded in the analysis of acute kidney injury. Reference: White race.

Inflammatory Marker Levels

In comparison with White patients, Black patients had higher initial and peak plasma D-dimer (mean ± SEM initial D-dimer: 1676.3 ± 229.5 vs. 818.0 ± 124.1 ng/mL FEU; peak D-dimer: 4189.6 ± 397.8 vs. 2117.5 ± 235.6, both p <0.001), ESR (initial ESR: 76.8 ± 1.5 vs. 62.7 ± 1.4 mm/h; peak ESR: 81.6 ± 1.5 vs. 67.2 ± 1.4, both p <0.001), plasma ferritin (initial ferritin: 1310.9 ± 141.4 vs. 801.3 ± 62.3 ng/mL; peak ferritin: 2372.9 ± 221.8 vs. 1399.6 ± 122.1, both p <0.05), and serum LDH (initial LDH: 403.1 ± 13.5 vs. 348.9 ± 8.1 U/L; peak LDH 536.6 ± 19.0 vs. 467.6 ± 18.9, both p <0.001; Figs. 2 and 3). Black patients had lower lowest absolute lymphocyte counts than White patients (0.8 ± 0.03×103 vs. 0.9 ± 0.03×103 cells/μL, p = 0.022). Subgroup analysis showed that initial ESR and plasma D-dimer, and peak ESR, plasma D-dimer, and serum LDH, were higher in Black patients than in White patients across all age and sex groups (age ≥65 and <65 years, male and female, Figs. 2 and 3). In multivariable models, Black race was associated with increased both initial and peak levels of D-dimer, ESR, ferritin, and LDH, after adjusting for potential confounders (all p <0.05; Tables 3 and 4).

Inflammatory marker levels and oxygen saturation on admission in Black and White hospitalized COVID-19 patients, stratified by age, sex, presence of acute kidney injury (AKI), and pulmonary embolism (PE). Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; PE, pulmonary embolism. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. “*” denotes statistically significant difference between Black and White patients (p <0.05).

Peak inflammatory marker levels in Black and White hospitalized COVID-19 patients, stratified by age, sex, presence of acute kidney injury (AKI), and pulmonary embolism (PE). Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; PE, pulmonary embolism. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Data included highest levels of D-dimer, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase and absolute neutrophil count, and lowest level of absolute lymphocyte count. “*” denotes statistically significant difference between Black and White patients (p <0.05).

Since race was associated with AKI and PE, additional analysis was performed to further investigate racial differences in inflammatory burden specifically in patients with AKI and PE. Compared with White AKI patients, Black AKI patients had higher initial plasma D-dimer (mean ± SEM: 2238.2 ± 430.3 vs. 1337.8 ± 357.5 ng/mL FEU, p = 0.048), ESR (83.3 ± 2.2 vs. 69.9 ± 2.9 mm/h, p <0.001), and serum LDH (471.6 ± 26.8 vs. 400.7 ± 24.9 U/L, p <0.001; Fig. 2). In addition, Black AKI patients had higher peak ESR than White AKI patients (88.2 ± 2.2 vs. 74.3 ± 2.9 mm/h, p <0.001; Fig. 3). No significant difference in the rate of positive proteinuria measured by urine dipstick was found between Black and White patients with AKI (21.8% vs. 23.7%, p = 0.673).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study, we compared hospital outcomes and inflammatory marker levels between Black and White hospitalized COVID-19 patients at BMC, the largest safety-net hospital in New England.21 We found in the multivariate analysis that AKI and PE were associated with self-identified Black race after adjustment for potential confounders. In addition, we observed higher levels of inflammatory markers (ESR, D-dimer, ferritin, and LDH) in Black patients compared with White patients, suggesting racial differences in inflammatory burden from COVID-19. We also found in the univariate analysis that Black patients tended to have higher rates of in-hospital death and myocardial infarction than White patients. However, these outcomes were no longer associated with Black race after adjustment for potential confounders such as age and underlying comorbidities, indicating that the difference found in the univariate analysis is likely due to the fact that Black patients were older and had higher rates of pre-existing comorbidities and receipt of chronic medications that might affect the pathogenesis and outcomes of COVID-19.22,23 In addition, a smaller proportion of them were treated with remdesivir.

It has been proposed that thrombosis risk in COVID-19 not only is explained by critical illness and respiratory failure, but also may be associated with pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy.24 The approximately twofold increased adjusted odds of PE among Black hospitalized COVID-19 patients observed in our study is in line with the observation in the general population without COVID-19 that Black Americans have a 67–104% higher age-sex adjusted rate of venous thromboembolism than White Americans.25,26,27 This is generally understood to be due to the fact that Black individuals may have had higher circulating levels of von Willebrand Factor and Factor VIII, which are shown to independently confer risk of venous thromboembolism.25,28 Furthermore, in our study, increased D-dimer levels were observed in Black patients regardless of age, sex, and comorbidities. This finding is also consistent with that of previous studies in non-COVID individuals,29,30 suggesting that Black individuals might have higher clot formation and breakdown, even in the absence of detected venous thromboembolism. Of note, however, Black patients were less likely to have received remdesivir, and this discrepancy also may have affected outcomes.

AKI is a common complication of COVID-19, with the reported incidence ranging from 0.1 to 29% among hospitalized patients.31,32,33,34,35,36 It has been proposed that COVID-19 impacts the kidney via multiple mechanisms including cytokine storm and resulting multi-organ system failure.36,37 COVID-19 not only causes intrarenal inflammation and increased vascular permeability, but also leads to intravascular volume depletion and cardiomyopathy, thereby precipitating cardio-renal syndrome.38 Other proposed mechanisms for COVID-associated kidney injury include direct cytopathic effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the podocytes and renal tubules39 and the consequences of multi-organ dysfunction such as acute tubular necrosis secondary to rhabdomyolysis,40 renal medullary hypoxia secondary to ARDS and renal compartment syndrome due to high peak airway pressure, and intraabdominal hypertension.41

Our finding that Black patients with COVID-19 had approximately 2.2 times increased odds of developing in-hospital AKI after adjusting for potential confounders has confirmed those of the previous studies in different populations that reported 1.2–2.0 times increased odds of AKI among Black COVID-19 patients.36,42,43 It is also worth noting that in the population without COVID-19, Black individuals were found to be at approximately 1.2 times higher risk of AKI compared with White individuals even after controlling for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, kidney markers, and time-varying number of hospitalizations.44 Although the exact mechanism of racial differences in risk of COVID-associated AKI is still to be elucidated, some possible explanations include genetic polymorphisms and acquired factors. For example, ACE2, IL-6, and AChE genes have been associated with higher COVID-19 disease burden and have been shown to be more prevalent in the Black population.45,46,47,48 Furthermore, Black individuals are at a higher risk for vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D has been proposed to be protective against COVID-19 infectivity and severity as it modulates the immune system by suppressing T helper 1 immune profile and upregulating the regulatory T cell expression, thereby reducing the severity of cytokine storm.49,50,51,52 Therefore, Black patients may be at higher risk than White patients of cytokine storm and resulting systemic and intrarenal inflammation. This is also supported by the higher levels of inflammatory markers among Black patients observed in our study. Of particular interest is that, in our study, higher levels of inflammatory markers were also observed in Black patients with AKI compared with White patients with AKI.

Another potential explanation for racial differences in AKI is related to collapsing glomerulopathy predisposed by APOL1 high-risk allele. Approximately 14% of the Black population are homozygous for the G1 or G2 APOL1 risk alleles known to be strongly associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy.53,54 Similar to that observed in the context of viral infections and conditions that upregulate levels of interferon, the systemic inflammatory response in COVID-19 is thought to interact with the APOL1 variant gene, leading to impairment in glomerular epithelial cell autophagy, mitochondrial function, and cell injury, thereby causing collapsing glomerulopathy and AKI with nephrotic-range proteinuria.53,55 This proposed mechanism is strengthened by the recent case series in six Black patients with APOL1 high-risk genotype who developed biopsy-proven collapsing glomerulopathy associated with COVID-19.56

This study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this is a retrospective study so there are inherent limitations in available information and/or documentation (e.g., laboratory data, comorbidities, and hospital outcomes). Second, we extracted data from records of patients who were hospitalized between March and August 2020. Therefore, the treatment strategy in our study may not be representative of the most updated standard treatment for COVID-19. Third, higher rates of occult cardio-metabolic conditions and CKD have been observed in the Black populations.44,57,58 These conditions are also risk factors for PE and/or AKI. Although multivariate analysis was performed to adjust for recognized comorbidities including obesity, the apparent increased risks for PE and AKI might still be driven by the higher rates of undiagnosed underlying conditions in the Black population including hypertension and type 2 diabetes.59 Furthermore, we were unable to control for timing of presentation, which might also impact the effects of treatment for COVID-19 with remdesivir and/or dexamethasone.60,61 Therefore, some of the observed differences in clinical outcomes and inflammatory marker levels may be due to the difference in timing of presentation for care between Black and White patients. Additionally, data on staging of AKI including change of creatinine from baseline as well as quantification of proteinuria were not available for this study. Thus, we were unable to compare the severity of AKI between the two racial groups. It should also be noted that there is evidence suggesting that pulse oximetry is systematically less accurate in Black individuals.62 This may lead to bias in ascertainment of hypoxemia based on oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry. Finally, as our study focused only on hospitalized patients, the result may not be generalizable to the rest of the COVID-19 population.

Based on the results of our study along with others, it appears that the racial disparities in COVID-associated outcomes are due in part to pre-existing comorbidities and possibly other biologic variables that were not directly measured in this study such as vitamin D status, APOL1 genotype, or other immune phenotyping. Future studies are needed to study racial differences in such biologic factors to more clearly delineate causation.

It is apparent from many prior studies that higher rates of infection, morbidity, and mortality among Black patients are due to socioeconomic factors as a by-product of systemic racism. Therefore, it is important to employ interventions to mitigate these disparities. Diagnosing occult comorbidities, aggressive risk factor modification, and providing health education around reducing COVID risk are critical. As vaccines enter the phases of community-wide rollout, promoting vaccine awareness and uptake among Black patients may help improve the clear health disparities. These will require the mutual inclusions and collaboration of local government, various organizations, policymakers, and researchers to mend healthcare in the populations disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

Equally important is that biologic risk factors that can be measured are increasingly likely to be responsible for many of the differences seen in prevalence of comorbidities and their morbidity and mortality among races. As research advances to uncover biologic and genetic influences, we as others find it prudent to report the disparities in outcome in the COVID-19 pandemic. In our study, we used self-reported race, a social construct, as the primary exposure variable despite its flaw as a variable to categorize differences in our population. Racism and social and economic disadvantage partially explain the health disparities seen in racial groups. There is also an urgent need to further define the biologic and genetic factors driving outcomes in COVID-19. Defining this difference in the case of COVID-19, an infection with high mortality, will help elucidate the contributors of social determinants of health and structural racism in COVID-19 health outcomes. As more information is gathered on COVID-19, the genetic, biologic, and social influences must be urgently addressed to investigate racial disparities in health outcomes.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this retrospective cohort study of Black and White COVID-19 patients revealed increased rates of in-hospital death, myocardial infarction, PE, and AKI for Black patients that could be accounted for by confounders (such as comorbidities). Only PE and AKI remained significantly associated with Black race. The increased risks of these conditions are likely driven by a combination of systemic racism that results in differences in occult underlying comorbidities and biologic variables that were not directly measured in this study such as clotting factors, vitamin D status, APOL1 high-risk allele, and immune phenotyping. Studies are needed to further investigate the presence and biological mechanisms of racial differences in inflammatory burden and clinical outcomes of COVID-19.

References

Riley WJ. Health disparities: gaps in access, quality and affordability of medical care. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2012;123:167-74.

Price JH, Khubchandani J, McKinney M, Braun R. Racial/ethnic disparities in chronic diseases of youths and access to health care in the United States. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:787616. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/787616

LaVeist TA, Gaskin D, Richard P. Estimating the Economic Burden of Racial Health Inequalities in the United States. International Journal of Health Services. 2011;41(2):231-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.41.2.c

Quiñones AR, Botoseneanu A, Markwardt S, Nagel CL, Newsom JT, Dorr DA, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218462-e. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218462

Grams ME, Chow EKH, Segev DL, Coresh J. Lifetime incidence of CKD stages 3-5 in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(2):245-52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.009

Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Mode N, Dore GA, Canas JA, Eid SM, et al. Racial disparities in adult all-cause and cause-specific mortality among us adults: mediating and moderating factors. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3744-z

Bryson CL, Ross HJ, Boyko EJ, Young BA. Racial and Ethnic Variations in Albuminuria in the US Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Population: Associations With Diabetes and Level of CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2006;48(5):720-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.023

Andermann A, Collaboration C. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):E474-E83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160177

Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi Z-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7

The Lancet Infectious D. COVID-19, a pandemic or not? Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):383. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30180-8

Kullar R, Marcelin JR, Swartz TH, Piggott DA, Macias Gil R, Mathew TA, et al. Racial Disparity of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in African American Communities. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(6):890-3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa372

Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4

Racial data transparency. Center JHUR. 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/racial-data-transparency. .

COVID-19 Cases, Hospitalizations, and Deaths, by Race/Ethnicity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/covid-data/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.pdf. .

Golestaneh L, Neugarten J, Fisher M, Billett HH, Gil MR, Johns T, et al. The association of race and COVID-19 mortality. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100455

Louis-Jean J, Cenat K, Njoku CV, Angelo J, Sanon D. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Racial Disparities: a Perspective Analysis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(6):1039-45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00879-4

Snowden LR, Graaf G. COVID-19, Social Determinants Past, Present, and Future, and African Americans' Health. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(1):12-20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00923-3

Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(26):2534-43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa2011686

Rentsch CT, Kidwai-Khan F, Tate JP, Park LS, King JT, Skanderson M, et al. Covid-19 by Race and Ethnicity: A National Cohort Study of 6 Million United States Veterans. medRxiv. 2020:2020.05.12.20099135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.12.20099135

Komaromy M, Harris, Koenig MRM, Tomanovich MM, Ruiz-Mercado G, Barocas JA. Caring for COVID's most vulnerable victims: a safety-net hospital responds. Res Sq. 2020:rs.3.rs-97328. doi:https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-97328/v1

Yan H, Valdes AM, Vijay A, Wang S, Liang L, Yang S, et al. Role of Drugs Used for Chronic Disease Management on Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19: A Large Case-Control Study. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2020;108(6):1185-94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2047

Vila-Córcoles A, Ochoa-Gondar O, Satué-Gracia EM, Torrente-Fraga C, Gomez-Bertomeu F, Vila-Rovira A, et al. Influence of prior comorbidities and chronic medications use on the risk of COVID-19 in adults: a population-based cohort study in Tarragona, Spain. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e041577. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041577

Fogarty H, Townsend L, Ni Cheallaigh C, Bergin C, Martin-Loeches I, Browne P, et al. COVID19 coagulopathy in Caucasian patients. British Journal of Haematology. 2020;189(6):1044-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16749

Folsom AR, Basu S, Hong C-P, Heckbert SR, Lutsey PL, Rosamond WD, et al. Reasons for Differences in the Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism in Black Versus White Americans. Am J Med. 2019;132(8):970-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.021

Zakai NA, McClure LA, Judd SE, Safford MM, Folsom AR, Lutsey PL, et al. Racial and regional differences in venous thromboembolism in the United States in 3 cohorts. Circulation. 2014;129(14):1502-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006472

Zakai N, Lutsey P, Folsom A, Cushman M. Black-White Differences In Venous Thrombosis Risk: the Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE). Blood. 2010;116(21):478. doi:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V116.21.478.478

Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Steffen LM, Green D, Barr RG, Herrington D, et al. Plasma hemostatic factors and endothelial markers in four racial/ethnic groups: the MESA study. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2006;4(12):2629-35. doihttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02237.x

Khaleghi M, Saleem U, McBane RD, Mosley TH, Jr., Kullo IJ. African-American ethnicity is associated with higher plasma levels of D-dimer in adults with hypertension. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(1):34-40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03215.x

O’Bryan TA, Agan BK, Tracy RP, Freiberg MS, Okulicz JF, So-Armah K, et al. Brief Report: Racial Comparison of D-Dimer Levels in US Male Military Personnel Before and After HIV Infection and Viral Suppression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(5):502-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001626

Guan W-j, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(18):1708-20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829-38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.005

Zahid U, Ramachandran P, Spitalewitz S, Alasadi L, Chakraborti A, Azhar M, et al. Acute Kidney Injury in COVID-19 Patients: An Inner City Hospital Experience and Policy Implications. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51(10):786-96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000511160

Mohamed MMB, Lukitsch I, Torres-Ortiz AE, Walker JB, Varghese V, Hernandez-Arroyo CF, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Urban New Orleans. Kidney360. 2020;1(7):614. doi:https://doi.org/10.34067/KID.0002652020

Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia JA, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020;8(5):475-81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5

Nimkar A, Naaraayan A, Hasan A, Pant S, Durdevic M, Suarez CN, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Acute Kidney Injury and Its Effect on Mortality in Patients Hospitalized From COVID-19. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes. 2020;4(6):687-95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.07.003

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

Bansal M. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(3):247-50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.013

Martinez-Rojas MA, Vega-Vega O, Bobadilla NA. Is the kidney a target of SARS-CoV-2? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2020;318(6):F1454-F62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00160.2020

Taxbro K, Kahlow H, Wulcan H, Fornarve A. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury in severe COVID-19 infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(9):e237616. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-237616

Ronco C, Reis T. Kidney involvement in COVID-19 and rationale for extracorporeal therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(6):308-10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-0284-7

Hirsch JS, Ng JH, Ross DW, Sharma P, Shah HH, Barnett RL, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):209-18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006

Bowe B, Cai M, Xie Y, Gibson AK, Maddukuri G, Al-Aly Z. Acute Kidney Injury in a National Cohort of Hospitalized US Veterans with COVID-19. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2020:CJN.09610620. doi:https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.09610620

Grams ME, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Estrella MM, Foster MC, Tin A, et al. Explaining the racial difference in AKI incidence. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(8):1834-41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2013080867

Phillips N, Park I-W, Robinson JR, Jones HP. The Perfect Storm: COVID-19 Health Disparities in US Blacks. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020:1-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00871-y

Calcagnile M, Forgez P, Iannelli A, Bucci C, Alifano M, Alifano P. ACE2 polymorphisms and individual susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection: insights from an <em>in silico</em> study. bioRxiv. 2020:2020.04.23.057042. doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.23.057042

Slopen N, Lewis TT, Gruenewald TL, Mujahid MS, Ryff CD, Albert MA, et al. Early life adversity and inflammation in African Americans and whites in the midlife in the United States survey. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(7):694-701. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e9c16f

Vinciguerra M, Greco E. Sars-CoV-2 and black population: ACE2 as shield or blade? Infect Genet Evol. 2020;84:104361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104361

Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266-81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra070553

Kumar R, Rathi H, Haq A, Wimalawansa SJ, Sharma A. Putative roles of vitamin D in modulating immune response and immunopathology associated with COVID-19. Virus Res. 2021;292:198235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198235

Charoenngam N, Holick MF. Immunologic Effects of Vitamin D on Human Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2097. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072097

Charoenngam N, Shirvani A, Holick MF. Vitamin D and Its Potential Benefit for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Endocr Pract. 2021:S1530-891X(21)00087-2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2021.03.006

Velez JCQ, Caza T, Larsen CP. COVAN is the new HIVAN: the re-emergence of collapsing glomerulopathy with COVID-19. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2020;16(10):565-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-0332-3

Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, Johnson RC, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, et al. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1175-84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.226

Nichols B, Jog P, Lee JH, Blackler D, Wilmot M, D'Agati V, et al. Innate immunity pathways regulate the nephropathy gene Apolipoprotein L1. Kidney Int. 2015;87(2):332-42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2014.270

Wu H, Larsen CP, Hernandez-Arroyo CF, Mohamed MMB, Caza T, Sharshir MD, et al. AKI and Collapsing Glomerulopathy Associated with COVID-19 and <em>APOL</em><span class="sc"><em>1</em></span> High-Risk Genotype. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2020;31(8):1688. doi:https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020050558

Graham G. Disparities in cardiovascular disease risk in the United States. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11(3):238-45. doi:https://doi.org/10.2174/1573403×11666141122220003

Laster M, Shen JI, Norris KC. Kidney Disease Among African Americans: A Population Perspective. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(5 Suppl 1):S3-S7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.021

Kim EJ, Kim T, Conigliaro J, Liebschutz JM, Paasche-Orlow MK, Hanchate AD. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Diagnosis of Chronic Medical Conditions in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1116-23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4471-1

Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Final Report. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;383(19):1813-26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2007764

Ahmed MH, Hassan A. Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): a Review. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020:1-10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00610-8

Feiner JR, Severinghaus JW, Bickler PE. Dark Skin Decreases the Accuracy of Pulse Oximeters at Low Oxygen Saturation: The Effects of Oximeter Probe Type and Gender. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2007;105(6).

Funding

Nipith Charoenngam receives the institutional research training grant from the Ruth L. Kirchstein National Research Service Award program from the National Institutes of Health (2 T32 DK 7201-42). Caroline M. Apovian is supported by P30 DK046200. Titilayo O. Ilori is supported by a K23 career development grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23DK11954201). Natasha S. Hochberg is funded in part by a grant from the Warren Alpert Foundation and Boston University School of Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We thank Arash Shirvani, PhD, MD, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Nutrition and Weight Management, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA, who provided advice and assistance in statistical analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Michael F. Holick is a former consultant for Quest Diagnostics Inc., a consultant for Biogena Inc. and Ontometrics Inc., and on the speaker’s Bureau for Abbott Inc. Caroline M. Apovian reports receiving personal fees from Nutrisystem, Zafgen, Sanofi-Aventis, Orexigen, EnteroMedics, GI Dynamics, Scientific Intake, Gelesis, Novo Nordisk, SetPoint Health, Xeno Biosciences, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, and Takeda outside of the funded work; reports receiving grant funding from Aspire Bariatrics, GI Dynamics, Orexigen, Takeda, the Vela Foundation, Gelesis, Energesis, Coherence Lab, and Novo Nordisk outside of the funded work; and reports past equity interest in ScienceSmart, LLC.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Charoenngam, N., Ilori, T.O., Holick, M.F. et al. Self-identified Race and COVID-19-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Inflammation: a Retrospective Cohort Study of Hospitalized Inner-City COVID-19 Patients. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 3487–3496 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06931-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06931-1