Abstract

Background

This is the first randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of note template design on note quality using a simulated patient encounter and a validated assessment tool.

Objective

To compare note quality between two different templates using a novel randomized clinical simulation process.

Design

A randomized non-blinded controlled trial of a standard note template versus redesigned template.

Participants

PGY 1-3 IM residents.

Interventions

Residents documented the simulated patient encounter using one of two templates. The standard template was modeled after the usual outpatient progress note. The new template placed the assessment and plan section in the beginning, grouped subjective data into the assessment, and deemphasized less useful elements.

Main Measures

Note length; time to note completion; note template evaluation by resident authors; note evaluation by faculty reviewers.

Key Results

36 residents participated, 19 randomized to standard template, 17 to new. New template generated shorter notes (103 vs 285 lines, p < 0.001) that took the same time to complete (19.8 vs 21.6 min, p = 0.654). Using a 5-point Likert scale, residents considered new notes to have increased visual appeal (4 vs 3, p = 0.05) and less redundancy and clutter (4 vs 3, p = 0.006). Overall template satisfaction was not statistically different. Faculty reviewers rated the standard note more up-to-date (4.3 vs 2.7, p = 0.001), accurate (3.9 vs 2.6, p = 0.003), and useful (4 vs 2.8, p = 0.002), but less organized (3.3 vs 4.5, p < 0.001). Total quality was not statistically different.

Conclusions

Residents rated the new note template more visually appealing, shorter, and less cluttered. Faculty reviewers rated both note types equivalent in the overall quality but rated new notes inferior in terms of accuracy and usefulness though better organized. This study demonstrates a novel method of a simulated clinical encounter to evaluate note templates before the introduction into practice.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT04333238

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Providers often decry the state of current notes with the trend towards copy-forwarding as well as the inclusion of excess automatically imported data.1,2 The current literature on note reform describes the introduction of new note templates, often paired with note-writing education. Thus far, studies have relied mainly on pre/post analyses, assessment using provider opinion, and non-validated survey instruments.3,4,5,6,7,8 The purpose of this study was twofold: first, to implement a novel process for note evaluation using rigorous methodology of a randomized controlled study design based on a standardized, simulated patient encounter and, second, to assess for differences in perceived note quality between notes derived from a new note template versus a standard note template.

The Subjective Objective Assessment Plan (SOAP) note was introduced in 1964 as an organizational framework for clinical reasoning.9 By guiding health professionals to process information in a predictable format, it diminishes cognitive load and promotes thoughtful and comprehensive medical decision-making. SOAP notes have become one of the most common methods of written communication among health professionals. With the widespread migration to electronic health records (EHRs), the SOAP note was largely converted from paper to electronic format.

Several recent developments have called for a revisiting of the organization of the medical note. For example, data from physician surveys and eye-tracking data show that the assessment and plan portions are typically read first and reviewed the longest, suggesting that there might some benefit to re-ordering the SOAP format.10,11,12 Furthermore, by mandating that certain elements always be included in notes, regulatory and billing requirements may have functioned to increase the length of the standard note and restrict innovation in note composition.13 This additional material automatically embedded within the note is without demonstrated benefit and theoretically introduces the harm of diverting attention away from more important clinical information. However, compliance with these regulations does still allow for some flexibility in note design. EHRs can even facilitate experimentation with different note formats by including easily modifiable templates that can be shared between users and by allowing for customized auto-importing of data content. With ongoing research supporting behavioral economic approaches to modulate behavior, note templates are a logical vehicle to facilitate desired documentation and clinical practices.14,15

This merits additional focus, as notes are the vehicles through which all medical care is documented. We hypothesized that note format matters, and that it is possible to rigorously test the difference in note templates.

METHODS

The Notation Optimization through Template Engineering (NOTE) was a randomized clinical trial conducted from January 20, 2017, to April 26, 2017. The trial protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (IRB00117171).

A focus group composed of internal medicine residents and attending physicians was convened to design a new clinic note template reflecting the latest research and in concordance with the policy recommendations delineated by the American College of Physicians’ position statement on clinical documentation.16 The design principles were further based on collective experience and the large body of existing research about note composition (Appendix 1 in the supplementary material).3,5,10,11,17,18 The consensus was to generate a note based on the CAPS (Concern, Assessment, Plan, Supporting information) format.19 This structure improves upon the Assessment Plan Subjective Objective (APSO) note, which was rated favorably and felt to be faster to use than SOAP notes when studied in clinics at the University of Colorado.5 The CAPS note was further modified to eliminate auto-imported labs in an effort to reduce cognitive load for those who would read and interpret the note, which has sometimes been referred to as “note bloat.” Aspects of the note that may not be directly pertinent to the current presentation, such as template statements indicating that “medical history was reviewed and updated” or the review of systems section, were reduced in font size and placed at the end of the note.10,11,17

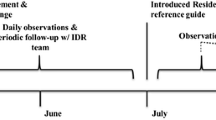

To evaluate the impact of the new note template, a non-blinded randomized controlled experiment was conducted (Fig. 1). All PGY 1–3 internal medicine residents based in one of the program’s housestaff primary care practices were eligible for participation. To simulate the usual clinical environment, residents were asked to complete this exercise during their actual clinic time, when scheduled patients did not present for their appointments or during other gaps in their schedules. Residents who agreed to participate were shown a simulated patient video of a clinical encounter (Appendix 2 in the supplementary material). Using the training environment of the EHR, all health elements of this simulated patient were replicated digitally, including prior notes, lab data, and vital signs. The residents were given instructions to watch the video and treat the virtual patient as if it were a real medical encounter and document accordingly. Residents were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to the current standard clinic note template (Appendix 3 in the supplementary material) or the new template. Residents were subsequently asked to evaluate their assigned note template using a brief survey (Appendix 4 in the supplementary material). The time to note completion was determined by an internal automated recording system and note length was measured by the total line number.

A second part of the note analysis involved having all notes reviewed by three attending general internal medicine outpatient clinicians and graded using a standardized rubric. These evaluators all served as preceptors in the housestaff primary care clinic and ranged from being 2 to 20 years post residency graduation. The QNOTE instrument, while validated on outpatient notes, was not selected for this study as it grades each historical element (social and family history, problem list, ROS, etc.) on a 3-point scale.20 The new note template deliberately deemphasizes and eliminates certain sections of the notes and would therefore always score lower than the standard note template. The PDQI-9, in contrast, does not grade each element of the note but rather assesses the overall note quality through its composite attributes (up-to-date, accurate, thorough, useful, organized, comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, internally consistent).21 To help ensure that notes were being graded using the same principles, the three reviewers first practiced using the PDQI-9 rubric on mock notes that were not part of the study. To give further guidance to the reviewers, explanations of grading parameters were provided (Appendix 5 in the supplementary material). To improve interrater reliability, if any two reviewers differed in a category by two or more points, the item was discussed amongst all reviewers, and a new score was reached by consensus.

Participant characteristics were compared between intervention and control groups using the chi-square test. Medians of note quality outcomes were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Ratings by faculty were compared using Student’s t test.

RESULTS

36 residents participated in the study; 19 were randomized to document using the control note and 17 to the intervention note. Intervention and control groups were not statistically different in terms of gender or post-graduate year. The intervention arm, using the new template, generated notes that were shorter in length (103 vs 285 lines, p < 0.001) but took the same time to compose (19.8 vs 21.6 min, p = 0.654). As assessed by a 5-point Likert scale, residents in the intervention arm felt the new notes had increased visual appeal (4 vs 3, p = 0.05) and had less redundancy and clutter (4 vs 3, p = 0.006). There was no statistical difference among residents in overall satisfaction or the perception of whether the notes reflected their thought process. Resident and note characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Faculty reviewers rated the control notes as more up-to-date (4.3 vs 2.7, p = 0.001), accurate (3.9 vs 2.6, p = 0.003), and useful (4 vs 2.8, p = 0.002). The intervention notes were rated as better organized (4.5 vs 3.3, p < 0.001). There was no statistical difference in total quality and the metrics of being comprehensible, succinct, synthesized, or internally consistent (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the NOTE trial is the first randomized controlled study to evaluate the impact of note templates on note quality using a standardized encounter, with validated assessment tools. The results show that EHR note templates had a mixed impact on certain elements of the note, but did not affect overall quality as assessed by faculty, nor template satisfaction as assessed by residents. Total note length, which might represent the inclusion of less relevant details, was reduced with the new note template. However, considering the lower score in usefulness, rendering the notes more concise may have come at the cost of eliminating certain information felt necessary for clinical care.

Regarding comparison of the two note types, there are several possible reasons for our findings. In striving to be succinct, the new template used in this study excluded nearly all auto-imported information. Relying on residents to manually enter data may have led to errors that negatively impacted the metrics of being up-to-date and accurate. Data transcription may also explain how the new note, which was smaller in size, took the same amount of time to complete. Similarly, overlap exists with the “useful” metric, which was graded by counting the number of chart deficiencies—including the volume of information that is inaccurate and not up-to-date. The other metrics that were not significantly different between note templates may be those that remain unaffected by different note templates. For example, all note templates include the assessment and plan sections, which often involve large amounts of free text. The composition of this section may have the largest impact on to what extent a note is succinct, synthesized, internally consistent, and comprehensible. Alternatively, this study may ultimately reflect the need to further optimize a new clinic note template in order to appreciate differences in note quality. Finally, as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid roll out new regulations regarding billing, which will greatly emphasize Medical Decision Making (Assessment and Plan) and de-emphasize other sections, it is important to have rigorous, standardized methods to test note quality.22

LIMITATIONS

Our study had several limitations. First, this was a single-center trial in an internal medicine resident clinic of an academic center in the USA, which may limit generalizability. Second, as it was labor-intensive to have multiple reviewers independently read and grade all notes on a 9-point scale, and then reach consensus, expanding the trial to greater numbers of participants was not feasible. The domains included in the PDQI-9 cannot capture every relevant feature of notes given the wide array of purposes that they serve, from efficiently communicating a patient’s plan to facilitating diagnostic reasoning. For this study, our research team felt it was important to utilize a validated outcome instrument in this type of randomized trial. Future research could also focus on note utility and on subjective clinician preferences for note templates. With a small sample size, the trial may have been underpowered to detect some differences in note quality. Third, residents had no opportunity to practice using the new note template before generating their assigned note. This may have negatively impacted the quality of the notes or caused them to take longer to compose. Fourth, despite efforts to create a high fidelity simulation including EHR integration, maintenance of clinic environment, and appointment time, note-writing behavior may be different with true patient encounters. Finally, there may be generational or experiential differences that led to different scoring of notes by residents versus faculty reviewers.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that a methodologically rigorous process, using a simulated patient encounter to create an EHR entry, can be used to evaluate the quality of notes generated by new templates. Documentation is a fundamental aspect of the practice of modern medicine, and research needs to focus on optimizing and standardizing what is currently a heterogeneous practice.23 While neither note in this trial was superior to the other in total quality, establishing a process for testing new templates may yield notes that enhance efficiency in documentation; increase productivity and provider and patient satisfaction; and ultimately, improve patient care.24,25 Future studies might consider other measures reflecting note quality or function with the ultimate goal of evaluating the effect of note templates on clinical outcomes. Considering the ubiquitous use of personalized note templates in clinical documentation, evaluating the broad impact of templates is fundamental to the practice of medicine.26,27

References

Hirschtick RE. A piece of my mind. Copy-and-paste. JAMA. 2006;295(20):2335-2336.

Han H, Lopp L. Writing and reading in the electronic health record: an entirely new world. Med Educ Online 2013;18:1-7.

Dean SM, Eickhoff JC, Bakel LA. The effectiveness of a bundled intervention to improve resident progress notes in an electronic health record. J Hosp Med 2015;10(2):104-107.

Aylor M, Campbell EM, Winter C, Phillipi CA. Resident Notes in an Electronic Health Record A Mixed-Methods Study Using a Standardized Intervention With Qualitative Analysis. Clin Pediatr 2016:0009922816658651.

Lin C-T, McKenzie M, Pell J, Caplan L. Health care provider satisfaction with a new electronic progress note format: SOAP vs APSO format. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(2):160-162.

Fanucchi L, Yan D, Conigliaro RL. Duly noted: Lessons from a two-site intervention to assess and improve the quality of clinical documentation in the electronic health record. Appl Clin Inform 2016;7(3):653-659.

Kahn D, Stewart E, Duncan M, et al. A Prescription for Note Bloat: An Effective Progress Note Template. J Hosp Med 2018;13(6):378-382.

Hyppönen H, Saranto K, Vuokko R, et al. Impacts of structuring the electronic health record: a systematic review protocol and results of previous reviews. Int J Med Inform 2014;83(3):159-169.

Weed LL. Medical Records That Guide and Teach. N Engl J Med 1968;278(11):593-600.

Brown PJ, Marquard JL, Amster B, et al. What do physicians read (and ignore) in electronic progress notes? Appl Clin Inform 2014;5(2):430-444.

Koopman RJ, Steege LMB, Moore JL, et al. Physician Information Needs and Electronic Health Records (EHRs): Time to Reengineer the Clinic Note. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28(3):316-323.

The AOA Guide: How to Succeed in the Third-Year Clerkships. https://www.jefferson.edu/content/dam/university/skmc/AOA/AOAStudy2018.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed 12/15/2020, 2020.

Weiner M. Forced Inefficiencies of the Electronic Health Record. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(11):2299-2301.

Atkins D. So Many Nudges, So Little Time: Can Cost-effectiveness Tell Us When It Is Worthwhile to Try to Change Provider Behavior? J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(6):783-784.

Chokshi SK, Troxel A, Belli H, et al. User-Centered Development of a Behavioral Economics Inspired Electronic Health Record Clinical Decision Support Module. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019;264:1155-1158.

Kuhn T, Basch P, Barr M, Yackel T. Medical Informatics Committee of the American College of P. Clinical documentation in the 21st century: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2015;162(4):301-303.

Clarke MA, Steege LM, Moore JL, Koopman RJ, Belden JL, Kim MS. Determining primary care physician information needs to inform ambulatory visit note display. Appl Clin Inform 2014;5(1):169-190.

Shoolin J, Ozeran L, Hamann C, Bria W. Association of Medical Directors of Information Systems consensus on inpatient electronic health record documentation. Appl Clin Inform 2013;4(2):293-303.

Styron JF, Evans PJ. The evolution of office notes and the electronic medical record: The CAPS note. Cleve Clin J Med 2016;83(7):542-544.

Burke HB, Hoang A, Becher D, et al. QNOTE: an instrument for measuring the quality of EHR clinical notes. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21(5):910-916.

Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, Siegler EL. Assessing Electronic Note Quality Using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform 2012;3(2):164-174.

https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/finalized-policy-payment-and-quality-provisions-changes-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-calendar. Published 2019. Updated 11/1/2019. Accessed 2/14/2020, 2020.

Neri PM, Volk LA, Samaha S, et al. Relationship between documentation method and quality of chronic disease visit notes. Appl Clin Inform 2014;5(2):480-490.

Edwards ST, Neri PM, Volk LA, Schiff GD, Bates DW. Association of note quality and quality of care: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23(5):406-413.

Embi PJ, Yackel TR, Logan JR, Bowen JL, Cooney TG, Gorman PN. Impacts of computerized physician documentation in a teaching hospital: perceptions of faculty and resident physicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(4):300-309.

Rizvi RF, Harder KA, Hultman GM, et al. A comparative observational study of inpatient clinical note-entry and reading/retrieval styles adopted by physicians. Int J Med Inform 2016;90:1-11.

Pollard SE, Neri PM, Wilcox AR, et al. How physicians document outpatient visit notes in an electronic health record. Int J Med Inform 2013;82(1):39-46.

Acknowledgments

We thank the internal medicine residents at the Osler Medicine Training Program at The Johns Hospital for their participation; Katherine Levy and Emily Levy for their inclusion in the simulated patient encounter video; and Dingfen Han for her guidance on statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The trial protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (IRB00117171).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Epstein, J.A., Cofrancesco, J., Beach, M.C. et al. Effect of Outpatient Note Templates on Note Quality: NOTE (Notation Optimization through Template Engineering) Randomized Clinical Trial. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 580–584 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06188-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06188-0