Abstract

Background

Clinical performance measures often require documentation of patient counseling by healthcare providers. Little is known about whether such measures encourage delivery of counseling or merely its documentation.

Objective

To assess changes in provider documentation of alcohol counseling and patient report of receiving alcohol counseling in the Veterans Administration (VA) from 2009 to 2012.

Design

Retrospective time-series analysis.

Participants

A total of 5413 men who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use at an outpatient visit and responded to a confidential mailed survey regarding alcohol counseling from a VA provider in the prior year.

Main Measures

Rates of provider documentation of alcohol counseling in the electronic health record and patient report of such counseling on the survey were assessed over 4 fiscal years. Annual rates were calculated overall and with patients categorized into four mutually exclusive groups based on their own reports of alcohol counseling (yes/no) and whether alcohol counseling was documented by a provider (yes/no).

Key Results

Provider documentation of alcohol counseling increased 23.6% (95% CI: 17.0, 30.2), from 59.4% to 83.0%, while patient report of alcohol counseling showed no significant change (4.0%, 95% CI: −2.3, 10.3), increasing from 66.1% to 70.1%. An 18.7% (95% CI: 11.7, 25.7) increase in the proportion of patients who reported counseling that was documented by a provider largely reflected a 14.7% decline (95% CI: 8.5, 20.8) in the proportion of patients who reported alcohol counseling that was not documented by a provider. The proportion of patients who did not report counseling but whose providers documented it did not show a significant change (4.9%, 95%CI: 0.0, 9.9).

Conclusions

If patient report is accurate, increased rates of documented alcohol counseling in the VA from 2009 to 2012 predominantly reflected improved documentation of previously undocumented counseling rather than delivery of additional counseling or increased documentation of counseling that did not meaningfully occur.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Patient counseling is a key process in clinical care but can be challenging to measure.1 Direct observation, audio-taping, and unannounced standardized patients are limited by observation bias, ethical challenges, and cost.2 , 3 Therefore, quality measures related to counseling typically rely on documentation by providers in the medical record.4 Yet providers frequently under-document5,6,7,8, – 9 and occasionally over-document 10 the content of medical visits, including counseling. Moreover, with electronic health records (EHRs) that facilitate the insertion of templated text, identical documentation may mask differences between substantive advice and the most brief mention.11 These problems have led to particular concern about performance measures based on provider documentation of counseling.1 , 12 , 13 Specifically, do such performance measures increase the delivery of counseling or merely its documentation?

The US Veterans Administration (VA) was an early adopter of performance measures, clinical reminders, and incentives to improve quality.14 In 2007, VA implemented a performance measure aimed at increasing alcohol counseling—often called “brief intervention”—for patients screening positive for unhealthy alcohol use. In 2008, a clinical reminder was embedded in the EHR to alert providers when patients screened positive. The alert provided guidance for and facilitated documentation of alcohol counseling.15,16, – 17 This approach was associated with increased rates of documented alcohol counseling for patients screening positive for alcohol misuse—from 6% in 2006 to 29% in 2008.15 In 2010, VA facilities were expected to meet a benchmark rate of 62% for documented alcohol counseling among patients screening positive for unhealthy alcohol use.18 From 2009 to 2012, VA national rates of documented alcohol counseling rose from 53% to 81%.18

This retrospective time series analysis examines provider documentation and patient report of alcohol counseling in the VA over 4 fiscal years (2009–2012). Patient report is used as a comparison standard to assess the extent to which increases in documented alcohol counseling were due to the additional delivery of counseling or merely changes in the pattern of documentation. Additional delivery of counseling would be expected to yield parallel increases in rates of provider documentation and patient report of counseling over time; a change only in provider documentation would not be expected to alter rates of patient-reported counseling. More specifically, improved provider documentation in cases where counseling was previously being performed but not documented (decrease in undocumented counseling) would be expected to reduce the subset of patients reporting having received counseling but whose providers did not document it. Additional provider documentation of counseling that did not meaningfully occur (increase in over-documentation) would be expected to increase the subset of patients who did not report counseling but whose providers documented it.

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Sample

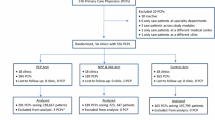

This study linked patient-level data from two sources: the VA Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP), a confidential, mailed patient satisfaction survey; and VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), a repository of clinical and administrative data. The study received approval and waivers of consent and HIPAA authorization from the VA Puget Sound and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute institutional review boards.

The SHEP survey is mailed to a random monthly sample of established VA patients with a recent outpatient visit. Patients with multiple visits are included in the sample pool once per quarter, and patients who have completed a survey within the prior year are excluded. During the 2009–2012 study period, a 10% random subsample of SHEP surveys included a question about receipt of alcohol counseling from a VA provider in the past year. Patients reporting no past-year drinking were asked to skip this question.

The study sample included patients who responded to the 2009–2012 SHEP survey question about alcohol counseling and had screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use at a VA clinic visit in the prior year. VA patients are screened annually for past-year unhealthy alcohol use with the three-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) questionnaire.19 A score of ≥ 5 is considered a positive screen and will activate a clinical reminder recommending alcohol counseling. VA performance measures target alcohol counseling only for patients with AUDIT-C scores of ≥5, regardless of gender. For women, optimal screening thresholds are lower19 and the likelihood of receiving appropriate alcohol counseling is lower.20,21,22, – 23 Given the limited number of women in the sample (n = 108), the study was restricted to men.

Measures

Patient-Reported Alcohol Counseling

Patient report of alcohol counseling was defined by an affirmative answer to the SHEP question, “In the past 12 months, has a VA doctor or other VA health care provider advised you about your drinking (to drink less or not to drink alcohol)?”

Provider-Documented Alcohol Counseling

Provider documentation of alcohol counseling was measured from VINCI using data tags resulting from use of the clinical reminder to document alcohol counseling. Although performance on VA measures is assessed by independent manual review of a random sample of chart notes, clinical reminders are routinely used to aid providers in meeting detailed documentation requirements.14 For example, the performance measure for alcohol counseling required specific documentation of both advice to reduce/abstain from drinking and feedback linking alcohol use to health.15 Provider use of the national electronic clinical reminder for alcohol counseling inserted text in the chart note that would meet these requirements. The clinical reminder would also record in VINCI that counseling was completed. As in prior studies, we combined all VINCI indicators of alcohol advice or counseling into a single dichotomous measure.16 , 24 Because the SHEP survey asked about counseling in the past year, we assessed provider documentation of alcohol counseling in the 365 days prior to the visit prompting the SHEP survey.

Time Periods

To assess changes over time, each patient was assigned to the fiscal year of the visit that prompted mailing of the SHEP survey.

Patient Characteristics

Patient age, race, ethnicity, and smoking status were obtained from responses to SHEP and supplemented with data from VINCI when incomplete. Patient satisfaction with the outpatient provider and VA healthcare in general were obtained from SHEP. Marital status, use of specialty addiction treatment, ICD-9 codes indicating the presence of mental health disorders including alcohol and other substance use, and the Charlson/Deyo comorbidity index25 were obtained from VINCI. AUDIT-C score range (5–7 points and 8–12 points) was drawn from the positive AUDIT-C on the day of or closest day preceding the visit prompting the SHEP survey. As a marker of time elapsed, we calculated the days between this positive AUDIT-C and the visit prompting the SHEP survey.

Analyses

Analyses were weighted to account for SHEP sampling design and non-response to the SHEP survey. The average response rate over the study period was 51% (55% in 2009, 53% in 2010, 51% in 2011, 48% in 2012). As in previous analyses,24 , 26 survey weights were truncated at 500 to limit the impact of any one respondent. Unweighted and weighted percentages were used to characterize the study sample.

To determine whether increases in documented alcohol counseling resulted from increased counseling or only from changes in documentation practices, the overall prevalence of patient-reported and provider-documented alcohol counseling for each of the 4 fiscal years was estimated using logistic regression. Two logistic models were estimated: one for patient-reported and one for provider-documented alcohol counseling. Although weighted for SHEP sampling and non-response, models did not adjust for patient or clinical information; each model included the 4 fiscal years as dummy variables. The estimated prevalence and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for patient-reported and provider-documented counseling in each fiscal year. For each counseling measure, the absolute percentage difference in prevalence between 2009 and 2012 was calculated. We calculated the p-value associated with a Wald statistic,27 , 28 calculating standard errors with the robust sandwich estimator29 to account for the survey weights, to assess for significant differences across the 4 years.

To further characterize the mechanisms underlying changes in rates of documented alcohol counseling, patients were categorized into four mutually exclusive groups based on the presence or absence of provider documentation and patient report of alcohol counseling. For each year, the proportion of patients in each of the four groups was estimated using weighted, unadjusted logistic regression, with fiscal years included as a dummy variable. Results are presented as the estimated prevalence of each group, with 95% CIs, for each fiscal year. The absolute percentage difference in prevalence between 2009 and 2012 is reported with p-values calculated as described above. All analyses were performed using STATA software (version 13.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 5413 male VA outpatients who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use at a VA visit were eligible for the study. The study population was mostly older, white, and currently or previously married. Over one-third of patients had a documented alcohol use disorder, and 39% had an affective disorder. One-quarter of patients had the qualifying AUDIT-C score ≥ 5 on the day of the visit triggering the SHEP survey, another quarter within the prior 3 months, and the remainder within the prior 4 to 12 months. Almost two-thirds had an AUDIT-C score of 5–7 points, with one-third scoring ≥8 (Table 1). Weights to account for survey sampling and non-response were truncated at 500 for 66 patients.

From 2009 to 2012, the overall prevalence of provider-documented alcohol counseling increased from 59.4% to 83.0% (p <0.001), with an absolute increase of 23.6% (95% CI: 17.0, 30.2). Over that time there was no significant change in patient-reported alcohol counseling, with rates increasing from 66.1% to 70.1% (p = 0.212), an absolute increase of 4.0% (95% CI: −2.3, 10.3; Fig. 1).

Table 2 shows the prevalence of patients categorized into four mutually exclusive groups based on the presence/absence of provider documentation and patient report of alcohol counseling. From 2009 to 2012, there was an 18.7% (95% CI: 11.7, 25.7) increase in the proportion of patients with both provider documentation and patient report of alcohol counseling (p <0.001). There was a 9.0% decline (95% CI: 4.4, 13.5) in the group of patients lacking both provider documentation and patient report (p <0.001). There was a 14.7% decline (95% CI: 8.5, 20.8) in the group of patients who reported counseling but whose counseling was not documented by a provider (p <0.001). For the group of patients who did not report counseling but had provider documentation of counseling, the absolute increase of 4.9% (95% CI: 0.0,9.9) was not statistically significant (p = 0.056).

DISCUSSION

This study used patient report to assess the extent to which increased rates of provider-documented alcohol counseling in the VA from 2009 to 2012 reflected additional delivery of counseling or simply changes in documentation. During this period, a large rise in overall prevalence of provider documentation was not matched by an increase in patient report of counseling—consistent with a change in documentation rather than an increase in counseling. The 18.7% increase in the proportion of patients who reported counseling and had provider documentation appeared to primarily reflect the 14.7% decline in the proportion of patients who reported counseling that was not documented by a provider. These findings are consistent with a large increase in documentation of counseling that was already occurring—i.e., a decrease in undocumented counseling. The change over time in the proportion of patients who did not report counseling but whose providers documented counseling—the pattern expected for over-documentation of counseling that did not meaningfully occur—was not significant (4.9%, 95% CI: 0.0, 9.9).

The creators of the VA performance measure, clinical reminder, and benchmark for alcohol counseling intended to increase delivery of alcohol counseling by providers. Critics of performance measurement might have expected this effort to result in over-documentation (i.e., providers using the clinical reminder to document alcohol counseling that they did not perform in a meaningful way).30 If patient report is an accurate measure of whether alcohol counseling occurred, the results of this study suggest that neither the intended additional counseling nor the feared over-documentation of counseling was the main cause of increased documentation. Rather, the main change from 2009 to 2012 appears to be improved provider documentation of alcohol counseling that was already occurring.

Standardizing and improving documentation allows individuals and institutions to receive credit for work performed, and may be an intermediate step in quality improvement. However, the primary goal of quality improvement is to effect a change in patient care, for example, increase actual counseling. By this standard, the changes from 2009 to 2012 are disappointing. Yet, throughout the study period, two-thirds of patients screening positive for unhealthy alcohol use recalled receiving counseling from a provider in the past year. This rate far exceeds national averages22 , 31 and likely reflects prior efforts. Before 2009, the VA saw increases in both provider documentation15 and patient report32 of counseling. It is possible that implementation of alcohol screening and the clinical reminder before 2009 led to increases in actual counseling, with subsequent efforts to incentivize a specific benchmark rate of counseling primarily yielding increased documentation.

This study has several important limitations. First, patient report is known to be an imperfect measure of the content of medical visits.2 Even when asked shortly after a medical encounter, patients both under-and over-report clinician counseling when compared to audiotape or trained observer.5 , 7,8, – 9 , 33,34,35, – 36 Patients may forget counseling that was provided or may not recognize motivational techniques as “counseling.” Conversely, patients may incorrectly assume that providers have delivered appropriate counseling, especially if they have a favorable view of their providers.37 Both effects might be stronger in this study, for which patients were asked to recall counseling over an entire year. It is possible that patients received undocumented counseling by staff administering the AUDIT-C, or even perceived the screening questions as alcohol counseling. If some patients always report that counseling occurred, even when it has not, a true increase in alcohol counseling might be masked and appear only as a change in documentation. Conversely, if some patients never report counseling, even when it has occurred, actual delivery and documentation of additional counseling could incorrectly appear to be over-documentation. However, there is no reason to believe that the validity of patient report of alcohol counseling would vary in response to incentives for VA leaders or clinicians, making it a useful comparison standard for understanding trends in documentation over time. A study using telephone interviews within 30 days of a positive AUDIT-C at a single VA center found similar rates of patient-reported alcohol counseling to those seen in this study: of patients who recalled questions about drinking, 70% reported receiving advice to cut down or abstain.23

In addition to problems intrinsic to patient report as a comparison standard, there are three primary limitations of this study. First, we did not assess free-text documentation of alcohol counseling entered without the use of the EHR clinical reminder. However, given the difficultly in meeting documentation requirements for the VA performance measure, we expected that most incentive-driven documentation would use the clinical reminder. Furthermore the annual rates of provider-documented alcohol counseling in this study are similar to the official national VA rates of provider documentation based on manual medical record review of sampled clinical notes (53% in 2009, 69% in 2010, 78% in 2011, 81% in 2012).18 Second, patient reports of alcohol counseling were only available for patients who reported alcohol consumption on the SHEP survey (others were directed to skip the question about alcohol-related counseling). Although the SHEP question regarding any drinking in the past year should capture most patients with a positive AUDIT-C in the prior year, those who recently quit drinking might be less likely to report past-year drinking on the SHEP survey, and therefore would be excluded from this study. Finally, despite weighting to account for SHEP’s sampling design and survey non-response, survey respondents may differ from other patients in unmeasured ways, particularly given SHEP’s tendency to over-sample patients with multiple clinic visits and very low response rate among younger patients. Given gender differences in counseling,20,21,22, – 23 results may not generalize to female patients.

This study has several strengths, primarily the comparison of patient report and provider documentation of counseling at the level of individual patients in a large national sample. Second, bias was limited, because providers in this study could not have known which patients would receive the SHEP survey. Others have found that provider documentation of tobacco advice doubled on days when providers knew post-visit patient surveys were being performed.38 Third, this study is restricted to patients with positive alcohol screening scores at clinical visits. Prior studies comparing rates of provider-documented and patient-reported alcohol counseling in the VA used AUDIT-C scores from the mailed SHEP survey rather than AUDIT-C scores obtained in clinic.24 , 32 As only 40% of patients with positive AUDIT-C screening by mail screen positive in the clinic setting,39 these prior studies likely included many patients who did not screen positive in clinic and therefore were ineligible for the performance measure.

This study adds to the literature on the accuracy of provider documentation of counseling and the use of such documentation for quality measurement. Prior studies have found that only 30–40% of tobacco and alcohol counseling is routinely documented by providers.5 , 8 Few studies have assessed changes in documentation of counseling, although one British study found that new financial incentives for tobacco counseling were followed by increasing rates of provider documentation, with no similar increase in patient report of counseling.13

Discussing the difficulty in measuring heart failure counseling on hospital discharge, Chassin concluded, “we need a better measure for this important process; until we find one, measuring a check-box serves only to give us a false sense of accomplishment and reward ‘gaming’.1” One option would be to add measures of counseling based on patient report on surveys. For alcohol, patient surveys that incorporate both alcohol screening questions and a question about whether counseling was performed could also limit the perverse incentives for “denominator management”: improving rates of counseling by discouraging patients from disclosing unhealthy alcohol use to clinicians.40 Of course, performance measures based on patient report might have their own limitations, especially if they encourage confrontational rather than patient-centered counseling. For smoking, patient report of counseling is a better predictor of future quit attempts and success than provider documentation.41 , 42 Future research should further assess the association between patient recall of counseling and behavior change. This study serves as a reminder that documented counseling is not the same as actual counseling, and more generally that users of performance measures must be mindful of potential gaps between what is measured and what is desired.

References

Chassin MR, Loeb JM, Schmaltz SP, Wachter RM. Accountability measures--using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):683–8.

Hrisos S, Eccles MP, Francis JJ, Dickinson HO, Kaner EFS, Beyer F, et al. Are there valid proxy measures of clinical behaviour? A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2009;4:37.

Weiner SJ, Schwartz A. Directly observed care: can unannounced standardized patients address a gap in performance measurement? J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(8):1183–7.

The Joint Commission. Performance Measurement [Internet]. [Accessed Jul 16, 2017 ]. https://www.jointcommission.org/performance_measurement.aspx.

Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Smith TF, Kelly R, Langa DM, Flocke SA, et al. How valid are medical records and patient questionnaires for physician profiling and health services research? A comparison with direct observation of patients visits. Med Care. 1998;36(6):851–67.

Rethans JJ, Martin E, Metsemakers J. To what extent do clinical notes by general practitioners reflect actual medical performance? A study using simulated patients. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44(381):153–6.

Dresselhaus TR, Peabody JW, Lee M, Wang MM, Luck J. Measuring compliance with preventive care guidelines: standardized patients, clinical vignettes, and the medical record. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15 (11):782–8.

Wilson A, McDonald P. Comparison of patient questionnaire, medical record, and audio tape in assessment of health promotion in general practice consultations. BMJ. 1994;309 (6967):1483–5.

Roter DL, Russell NK. Validity of physician self-report in tracking patient education objectives. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(1):27–38.

Dresselhaus TR, Luck J, Peabody JW. The ethical problem of false positives: a prospective evaluation of physician reporting in the medical record. J Med Ethics. 2002;28(5):291–4.

Coleman T. Do financial incentives for delivering health promotion counselling work? Analysis of smoking cessation activities stimulated by the quality and outcomes framework. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:167.

Wu W-C, Jiang L, Friedmann PD, Trivedi A. Association between process quality measures for heart failure and mortality among US veterans. Am Heart J. 2014;168(5):713–20.

Szatkowski L, McNeill A, Lewis S, Coleman T. A comparison of patient recall of smoking cessation advice with advice recorded in electronic medical records. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:291.

Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10 (11 Pt 2):828–36.

Lapham GT, Achtmeyer CE, Williams EC, Hawkins EJ, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Increased documented brief alcohol interventions with a performance measure and electronic decision support. Med Care. 2012;50(2):179–87.

Williams EC, Rubinsky AD, Chavez LJ, Lapham GT, Rittmueller SE, Achtmeyer CE, et al. An early evaluation of implementation of brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in the US Veterans Health Administration. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1472–81.

Williams EC, Lapham G, Achtmeyer CE, Volpp B, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Use of an electronic clinical reminder for brief alcohol counseling is associated with resolution of unhealthy alcohol use at follow-up screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25 Suppl 1:11–7.

Office of Analytics and Business Intelligence.

Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(7):1208–17.

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Determinants of physician discussion regarding tobacco and alcohol abuse. J Health Commun. 2007;12(6):513–25.

Kaner EF, Heather N, Brodie J, Lock CA, McAvoy BR. Patient and practitioner characteristics predict brief alcohol intervention in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51 (471):822–7.

Glass JE, Bohnert KM, Brown RL. Alcohol Screening and Intervention Among United States Adults who Attend Ambulatory Healthcare. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):739–45.

Farmer CM, Stahlman S, Hepner KA. “You Should Drink Less”: Frequency and Predictors of Discussions Between Providers and Patients About Reducing Alcohol Use. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(2):139–44.

Lapham GT, Rubinsky AD, Shortreed SM, Hawkins EJ, Richards J, Williams EC, et al. Comparison of provider-documented and patient-reported brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in VA outpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:159–66.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9.

Simonetti JA, Lapham GT, Williams EC. Association Between Receipt of Brief Alcohol Intervention and Quality of Care among Veteran Outpatients with Unhealthy Alcohol Use. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1097–104.

Wald A. Tests of Statistical Hypotheses Concerning Several Parameters When the Number of Observations is Large. Trans Am Math Soc. 1943;54(3):426–82.

Rotnitzky A, Jewell NP. Hypothesis testing of regression parameters in semiparametric generalized linear models for cluster correlated data. Biometrika. 1990;77(3):485–97.

Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–30.

Office of the Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Not all recommended fraud safeguards have been implemented in hospital EHR technology. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013.

McKnight-Eily LR, Liu Y, Brewer RD, Kanny D, Lu H, Denny CH, et al. Vital signs: communication between health professionals and their patients about alcohol use--44 states and the District of Columbia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(1):16–22.

Chavez LJ, Williams EC, Lapham GT, Rubinsky AD, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Changes in Patient-Reported Alcohol-Related Advice Following Veterans Health Administration Implementation of Brief Alcohol Interventions. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2016;77(3):500–8.

Shaikh U, Nettiksimmons J, Bell RA, Tancredi D, Romano PS. Accuracy of parental report and electronic health record documentation as measures of diet and physical activity counseling. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(2):81–7.

Pbert L, Adams A, Quirk M, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Luippold RS. The patient exit interview as an assessment of physician-delivered smoking intervention: a validation study. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 1999;18(2):183–8.

Ward J, Sanson-Fisher R. Accuracy of patient recall of opportunistic smoking cessation advice in general practice. Tob Control. 1996;5:110–3.

Flocke SA, Stange KC. Direct observation and patient recall of health behavior advice. Prev Med. 2004;38(3):343–9.

Saitz R, Horton NJ, Cheng DM, Samet JH. Alcohol counseling reflects higher quality of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1482–6.

Coleman T, Wilson A, Barrett S, Wynne A, Lewis S. Distributing questionnaires about smoking to patients: impact on general practitioners’ recording of smoking advice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:153.

Bradley KA, Lapham GT, Hawkins EJ, Achtmeyer CE, Williams EC, Thomas RM, et al. Quality Concerns with Routine Alcohol Screening in VA Clinical Settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):299–306.

Bradley KA, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Hawkins EJ, Harris AHS, Frey MS, et al. Measuring performance of brief alcohol counseling in medical settings: a review of the options and lessons from the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system. Subst Abuse. 2007;28(4):133–49.

Reeves GR, Wang TY, Reid KJ, Alexander KP, Decker C, Ahmad H, et al. Dissociation between hospital performance of the smoking cessation counseling quality metric and cessation outcomes after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168 (19):2111–7.

Nicholson JM, Hennrikus DJ, Lando HA, McCarty MC, Vessey J. Patient recall versus physician documentation in report of smoking cessation counselling performed in the inpatient setting. Tob Control. 2000;9(4):382–8.

Funding

Funded by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1R21AA020894-01A1).

Dr. Bradley is funded by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K24-AA022128).

Dr. Williams is funded by the Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development (CDA 12–276).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Eric Goemer assisted with manuscript preparation. Karin Nelson provided comments on a draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Prior Presentations

None.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Shortreed has worked on a grant awarded to Group Health Research Institute (GHRI) by Pfizer. She is also a co-investigator on grants awarded to GHRI from the Campbell Alliance, a consortium of pharmaceutical companies carrying out FDA-mandated studies regarding the safety of extended-release opioids. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Berger, D., Lapham, G.T., Shortreed, S.M. et al. Increased Rates of Documented Alcohol Counseling in Primary Care: More Counseling or Just More Documentation?. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 268–274 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4163-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4163-2