Abstract

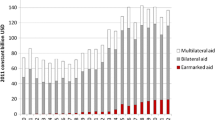

This study explores whether IMF-supported programs in low-income countries (LICs) catalyze Official Development Assistance (ODA). Based on a comprehensive set of ODA measures and using the Propensity Score Matching approach to address selection bias, we show that programs addressing policy or exogenous shocks have a significant catalytic impact on both the size and the modality of ODA. Moreover, for gross disbursements the impact is greatest when LICs are faced with substantial macroeconomic imbalances or large shocks. Results indicate a sharp difference between the responsiveness of multilateral and bilateral donors to programs. While multilateral donors significantly raise their gross and net disbursements to program countries, the aid allocation by bilateral donors, on both a gross and net basis, does not seem to be affected by programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

White and McGillivray (1995) provide a comprehensive survey of the literature prior to 1990.

While many studies measure good economic policies by lagged GDP growth per capita, low growth could also indicate high need of the recipient, which would lead to a negative relationship between aid and growth (Feeny and McGillivray, 2008).

Their results show that aid coordination is less likely in recipient countries that are important export markets for both donors in a pair and where both donors have a similar export structure. Moreover, competition for political support tends to undermine aid coordination of large DAC donors.

He reports that overall the “Nordic+” group of donors (Norway, Sweden, Finland, the United Kingdom, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Denmark) is more poverty-sensitive. For United States and France proximity seems to dominate, while for the United Kingdom and the Netherlands both proximity and poverty are significant. Dreher et al. (2015) find that geo-strategic and commercial motives matter for the allocation of German aid.

OECD (2008).

Academic studies report an adverse impact of donor fragmentation on transaction costs (Acharya et al. 2006; Anderson 2012; Lawson 2009), developing country administrative capacities (Kanbur 2003; Roodman 2006), and the quality of government bureaucracy in aid-recipient nations (Knack and Rahman 2007).

They find that the impact on bilateral aid flows to recipients in Africa and the Middle East and so-called donor ‘orphans’ is particularly pronounced. Overall the results suggest that donor coordination and free-riding are quantitatively less important than common donor interests and selectivity.

Private goods characteristics arise when donors obtain a benefit from providing aid that is not shared with other donors. On the other hand, public goods characteristics arise when donors use aid to promote shared goals and cannot exclude other donors enjoying such benefits (free-riding).

In his empirical work, Steinwand distinguishes between private and public goods aid by delivery channels: Aid using recipient government channels has a stronger private goods content, whereas aid channeled through nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) is more public goods oriented. Dreher et al. (2010) show that Swedish ODA provided through government channels is more responsive to Swedish political and economic interests than Swedish aid channelled through NGOs. On the other hand, they also find that needs-based targeting of aid by NGOs turns out to be surprisingly weak.

Han and Koenig-Archibugi (2015) examine the impact of aid fragmentation among health aid donors on child survival and report a U-shaped relationship: countries with a moderate number of donors fare better than countries with either few or many donors. Gutting and Steinwand (2015) find strong evidence that aid fragmentation significantly reduces the risk for political destabilization associated with aid shocks.

Their empirical approach models two dimensions: (i) the recipient’s selection for aid with the IMF program as one of the covariates and (ii) the magnitude of aid committed. They estimate these equations independently while providing the results with the Heckman correction for the second stage. They do not address the selection to IMF programs and use the GDP per capita and its growth rate to capture the recipient need.

Bird and Rowlands (2009a) highlight that the catalytic effect more likely reflects a convergence of interests between the IMF and aid donors while it does not seem to be induced by liquidity provided by the IMF and signaling.

DAC is a specialized committee of aid donors that includes 29 member countries, plus the European Union as a full member.

The minimum concessionality requirement is 25%, calculated using a discount factor of 10%.

October 2012 edition of Roodman (2006).

An SMP counts toward the track record of policy performance only if the Executive Board agrees that policies under the SMP meet the policy standard of an Upper Credit Tranche (UCT) arrangement.

In general, official loans that do not meet the concessionality requirement or allocated for non-developmental objectives such as military aid are classified as OOF. Loans with maturity of less than one year are also not counted as ODA.

PSM, a nonparametric estimator for the average treatment effect on the treated, is sometimes preferred to parametric regression models as it does not require to specify a specific parametric relation and a functional form (usually linear in regressions) between potential outcomes and control variables. In that regard, PSM is especially useful when there is a large reservoir of potential controls. Moreover, when there is poor overlap in controls for the treated and the non-treated (the so-called common support), the robustness of traditional methods that rely on functional form to extrapolate outside the common support becomes questionable. For matching estimators, treatment effects can only be estimated within the common support.

This study uses the nearest neighbor matching approach, which constructs a control group of countries by choosing those four non-program countries with probability of requesting a program as close as possible to that of the specific program country in question.

A delay of more than six months in completing a review owing to noncompliance with macro performance criteria is taken as an interruption, often accompanied by undrawn balances.

By this definition ECF arrangements that are on-track and not augmented to address immediate balance of payments needs are also included in normal episodes when other conditions are met as well. Only ECF augmentations or program interruptions during an ECF program signal the presence of an immediate financing need. Many LICs have back-to-back on-track ECF arrangements during the sample period.

Pooled probit models assume independence of observations over both t and i. A random effects (RE) probit model treats the individual specific effect, c i , as an unobserved random variable with \( {c}_i\mid {x}_{i t}\sim IN\left({\mu}_c,{\sigma}_c^2\right) \) if an overall intercept is excluded, and imposes independence of c i and x it . A fixed effects (FE) probit model treats c i as parameters to be estimated along with β, and does not make any assumptions about the distribution of c i given x it . This can be problematic in short panels as both β and c i are inconsistently estimated owing to an incidental parameters problem. Finally, a correlated random effects model relaxes independence between covariates and individual-specific effect using the Chamberlain (1982); Mundlak (1978) device under conditional normality. In this specification, the time average is often used to save on degrees of freedom.

In order to assess the macroeconomic policy stance based on a comprehensive set of complementary indicators, this study used a variant of the composite indicator introduced by Jaramillo and Sancak (2009). The version of this index that includes the black market premium was first used in Bal Gündüz (2009). The formula for the indicator is given by:

$$ {mitot}_{it}=\frac{ \ln \left(\frac{cpi_{it}}{cpi_{it-1}}\right)}{\sigma_{\Delta \ln (cpi)}}+\frac{ \ln \left(\frac{xr_{it}}{xr_{it-1}}\right)}{\sigma_{\Delta \ln (xr)}}-\frac{\frac{res_{it}-{res}_{it-1}}{mgs_{t-1}}}{\sigma_{\Delta res/{mgs}_{t-1}}}-\frac{\frac{gbal_{it}}{gdp_{it}}}{\sigma_{gbal/ gdp}}+\frac{ \ln \left(1+{blackpr}_{it}\right)}{\sigma_{\Delta \ln (xr)}} $$where mitot is the macroeconomic stability index for country i at time t, cpi is the consumer price index, xr is the exchange rate of national currency to U.S. dollar (an increase indicates a nominal depreciation), res is the stock of international reserves, mgs is the imports of goods and services, gbal is the government balance, gdp is the nominal GDP, blackpr is the black market premium, and σ is the standard deviation of each variable. Weights are inverses of the standard deviation of each component for all countries over the full sample after removing the outliers. Higher levels of mitot indicate increased macroeconomic instability.

See Bal Gündüz (2016) for other variables that could be significantly associated with the participation in IMF-supported programs but do not turn out to be significant, including variables capturing investors/donors’ willingness to meet financing needs, i.e., access to alternative financing, prior to financing events.

Using Moser and Sturm’s (2011) dataset a number of political variables are tested: previous IMF engagement, election dummy, political instability, social unrest, a measure of political rights and civil liberties (Freedom House Index), political globalization, temporary membership on the UN Security Council, relative size (share in world GDP and population), and variables capturing US influence (share of a country’s bilateral trade with the United States relative to the country’s GDP and how often countries do vote in line with the United States in the United Nations General Assembly).

The severe state failure events are identified from Political Instability Task Force (PITF) dataset. Four types of political crises are included in this dataset: revolutionary wars, ethnic wars, adverse regime changes, and genocides and politicides. From this dataset the variable SFTPMMAX, which presents the maximum magnitude of all events in a year, exceeding 3.9 is taken as a severe state failure event.

Our definition of program interruptions, a delay of more than six months in completing a review and associated suspension of financing, is likely to capture bilateral aid suspensions well. Molenaers et al. (2015) report that multilateral suspensions have the largest effect on the suspension of bilateral budget support. According to their findings bilateral donors are 45% more likely to suspend budget support when a multilateral agency also suspends.

Our definition of LICs is defined as those countries that were eligible to receive the IMF’s subsidized resources as of January 1st, 2010.

Available on the Review of International Organizations’s webpage.

As the focus is on the share of general budget support in total ODA to the recipient from the IDA or the EU, years with no ODA disbursements are excluded from the estimation sample for that donor.

Rosenbaum sensitivity analysis is conducted by using the stata ado command “rbounds” (Gangl 2004).

Robins (2002) expressed skepticism about the usefulness of sensitivity analysis as he proved that Rosenbaum’s Γ fit the criteria of a paradoxical measure: its magnitude increases as the analyst decreases the amount of hidden bias by measuring some of the unmeasured covariates. As such, this measure could be useful only if experts could provide a plausible and logically coherent range of Γ.

References

Acharya, A., De Lima, A. T. F., & Moore, M. (2006). Proliferation and fragmentation: Transactions costs and the value of aid. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(1), 1–21.

Aldasoro, I., Nunnenkamp, P., & Thiele, R. (2010). Less aid proliferation and more donor coordination? The wide gap between words and deeds. Journal of International Development, 22(7), 920–940.

Alesina, A., & Dollar, D. (2000). Who gives foreign aid to whom and why? Journal of Economic Growth, 5(1), 33–63.

Anderson, E. (2012). Aid fragmentation and donor transaction costs. Economics Letters, 117(3), 799–802.

Annen, K., & Kosempel, S. (2009). Foreign aid, donor fragmentation, and economic growth. The BE Journal of Macroeconomics, 9(1), 1–30.

Atoyan, R., & Conway, P. (2006). Evaluating the impact of IMF programs: A comparison of matching and instrumental-variable estimators. The Review of International Organizations, 1(2), 99–124.

Bal Gündüz, Y. (2009). Estimating demand for IMF financing by low-income countries in response to shocks. No. 9-263. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

Bal Gündüz, Y. (2016). The economic impact of short-term IMF engagement in low-income countries. World Development, 87, 30–49.

Bal Gündüz, Y., Ebeke, M. C., Hacibedel, M. B., Kaltani, M. L., Kehayova, M. V. V., Lane, M. C., … & Thornton, M. J. (2013). The Economic Impact of IMF-Supported Programs in Low-Income Countries. IMF occasional paper No. 277. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

Becker, T., & Mauro, P. (2007). Output drops and the shocks that matter. In IMF working paper 07/172. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Berthélemy, J. C. (2006). Bilateral donors’ interest vs. recipients’ development motives in aid allocation: Do all donors behave the same? Review of Development Economics, 10(2), 179–194.

Bigsten, A. (2006). Donor coordination and the uses of aid. Working papers in economics, 196. Göteborg University, Göteborg.

Bird, G. (2007). The IMF: A bird's eye view of its role and operations. Journal of Economic Surveys, 21(4), 683–745.

Bird, G., & Rowlands, D. (2002). Do IMF programmes have a catalytic effect on other international capital flows? Oxford Development Studies, 30(3), 229–249.

Bird, G., & Rowlands, D. (2007). The IMF and the mobilisation of foreign aid. Journal of Development Studies, 43(5), 856–870.

Bird, G., & Rowlands, D. (2009a). In J. M. Boughton & D. Lombardi (Eds.), Finance, development, and the IMF. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Bird, G., & Rowlands, D. (2009b). The IMF's role in mobilizing private capital flows: Are there grounds for catalytic conversion? Applied Economics Letters, 16(17), 1705–1708.

Bird, G., & Rowlands, D. (2009c). A disaggregated empirical analysis of the determinants of IMF arrangements: Does one model fit all? Journal of International Development, 21(7), 915–931.

Bird, G., & Rowlands, D. (2017). The effect of IMF Programmes on economic growth in low income countries: An empirical analysis. The Journal of Development Studies, 1–18.

Brück, T., & Xu, G. (2012). Who gives aid to whom and when? Aid accelerations, shocks and policies. European Journal of Political Economy, 28(4), 593–606.

Bruckner, M., & Ciccone, A. (2010). International commodity prices, growth, and the outbreak of civil war in sub-Saharan Africa. The Economic Journal, 120(544), 535–550.

Chamberlain, G. (1982). Multivariate regression models for panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 18(1), 5–46.

Claessens, S., Cassimon, D., & Van Campenhout, B. (2009). Evidence on changes in aid allocation criteria. The World Bank Economic Review, 23(2), 185–208.

Clist, P. (2011). 25 years of aid allocation practice: Whither selectivity? World Development, 39(10), 1724–1734.

Clist, P., Isopi, A., & Morrissey, O. (2012). Selectivity on aid modality: Determinants of budget support from multilateral donors. The Review of International Organizations, 7(3), 267–284.

Cottarelli, M. C., & Giannini, C. (2002). Bedfellows, hostages, or perfect strangers? Global capital markets and the catalytic effect of IMF crisis lending. In IMF working paper 02–193. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Dabla-Norris, E., & Bal Gündüz, Y. (2014). Exogenous shocks and growth crises in low-income countries: A vulnerability index. World Development, 59, 360–378.

Davies, R. B., & Klasen, S. (2015). Of donor coordination, free-riding, darlings, and orphans: The dependence of bilateral aid on other bilateral giving. Courant Research Centre: Poverty, Equity and Growth - Discussion Papers, No. 168.

Dehejia, R. H., & Wahba, S. (1999). Causal effects in nonexperimental studies: Reevaluating the evaluation of training programs. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(448), 1053–1062.

Djankov, S., Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2009). Aid with multiple personalities. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(2), 217–229.

Dollar, D., & Levin, V. (2006). The increasing selectivity of foreign aid, 1984–2003. World Development, 34(12), 2034–2046.

Dreher, A., Nunnenkamp, P., & Schmaljohann, M. (2015). The allocation of German aid: Self-interest and government ideology. Economics and Politics, 27(1), 160–184.

Dreher, A., Mölders, F., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2010). Aid delivery through non-governmental Organisations: Does the Aid Channel matter for the targeting of Swedish aid? The World Economy, 33(2), 147–176.

Easterly, W. (2007). Are aid agencies improving? Economic Policy, 22(52), 634–678.

Feeny, S., & McGillivray, M. (2008). What determines bilateral aid allocations? Evidence from time series data. Review of Development Economics, 12(3), 515–529.

Frot, E., & Santiso, J. (2011). Herding in aid allocation. Kyklos, 64(1), 54–74.

Frölich, M. (2004). Finite-sample properties of propensity-score matching and weighting estimators. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(1), 77–90.

Fuchs, A., Nunnenkamp, P., & Öhler, H. (2015). Why donors of foreign aid do not coordinate: The role of competition for export markets and political support. The World Economy, 38(2), 255–285.

Gangl, M. (2004). RBOUNDS: Stata module to perform Rosenbaum sensitivity analysis for average treatment effects on the treated. Statistical Software Components.

Gehring, K., Michaelowa, K., Dreher, A., & Spörri, F. (2015). Do we know what we think we know? Aid fragmentation and effectiveness revisited. Courant Research Centre: Poverty, Equity and Growth - Discussion Papers, No. 185.

Guillaumont, P., Jeanneney, S. G., & Wagner, L. (2017). How to take into account vulnerability in aid allocation criteria and lack of human capital as well: Improving the performance based allocation. World Development, 90, 27–40.

Gutting, R., & Steinwand, M. C. (2015). Donor fragmentation, aid shocks, and violent political Conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(3), 643–670.

Han, L., & Koenig-Archibugi, M. (2015). Aid fragmentation or aid pluralism? The effect of multiple donors on child survival in developing countries, 1990–2010. World Development, 76, 344–358.

Headey, D. (2008). Geopolitics and the effect of foreign aid on economic growth: 1970–2001. Journal of International Development, 20(2), 161–180.

Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. (1998). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator. The Review of Economic Studies, 65(2), 261–294.

Hnatkovska, V., & Loayza, N. (2005). In J. Aizenman & B. Pinto (Eds.), Volatility and growth in managing economic volatility and crises: A practitioner’s guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoeffler, A., & Outram, V. (2011). Need, merit, or self-interest—What determines the allocation of aid? Review of Development Economics, 15(2), 237–250.

International Monetary Fund. (2012). 2011 review of conditionality—Background paper: Outcomes of IMF-supported programs. International Monetary Fund: Washington D.C.

International Monetary Fund. (2016). The handbook of IMF facilities for low-income countries. International Monetary Fund: Washington D.C.

Jaramillo, L., & Sancak, C. (2009). Why has the grass been greener on one side of Hispaniola? A comparative growth analysis of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. IMF Staff Papers, 56, 323–349.

Kanbur, R. (2003). The economics of international aid. In S. Christophe-Kolm and J. Mercier-Ythier (Eds.), The economics of giving, reciprocity, and altruism. North-Holland.

Kimura, H., Mori, Y., & Sawada, Y. (2012). Aid proliferation and economic growth: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 40(1), 1–10.

Lawson, A. (2009). Evaluating the transaction costs of implementing the Paris Declaration. Concept Paper submitted by Fiscus Public Finance Consultants to the Secretariat for the Evaluation of the Paris Declaration, November.

Knack, S., & Rahman, A. (2007). Donor fragmentation and bureaucratic quality in aid recipients. Journal of Development Economics, 83(1), 176–197.

Mascarenhas, R., & Sandler, T. (2006). Do donors cooperatively fund foreign aid? The Review of International Organizations, 1(4), 337–357.

Mercer-Blackman, V., & Unigovskaya, A. (2004). Compliance with IMF program indicators and growth in transition economies. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 40(3), 55–83.

Minoiu, C., & Reddy, S. G. (2010). Development aid and economic growth: A positive long-run relation. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 50(1), 27–39.

Mody, A., & Saravia, D. (2006). Catalysing private capital flows: Do IMF Programmes work as commitment devices? The Economic Journal, 116(513), 843–867.

Molenaers, N., Gagiano, A., Smets, L., & Dellepiane, S. (2015). What determines the suspension of budget support? World Development, 75, 62–73.

Morris, S., & Shin, H. S. (2006). Catalytic finance: When does it work? Journal of International Economics, 70(1), 161–177.

Moser, C., & Sturm, J. E. (2011). Explaining IMF lending decisions after the cold war. The Review of International Organizations, 6(3–4), 307–340.

Mumssen, C., Bal Gündüz, Y., Ebeke, C., & Kaltani, L. (2013). IMF-supported programs in low income countries: Economic impact over the short and longer term. No:13–273. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

Mundlak, Y. (1978). On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica, 46, 69–85.

Nelson, S. C., & Wallace, G. P. (2016). Are IMF lending programs good or bad for democracy? The Review of International Organizations, 1–36.

Neumayer, E. (2003). The pattern of aid giving: The impact of good governance on development assistance. London: Routledge.

Neumayer, E. (2005). Is the allocation of food aid free from donor interest bias? Journal of Development Studies, 41(3), 394–411.

Nunnenkamp, P., Öhler, H., & Thiele, R. (2013). Donor coordination and specialization: Did the Paris Declaration make a difference? Review of World Economics, 149(3), 537–563.

OECD. (2008). The Paris Declaration on aid effectiveness and the Accra agenda for action. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2012). Aid effectiveness 2011: Progress in implementing the Paris Declaration. Paris: OECD.

Papageorgiou, C., Pattillo, C., Spatafora, N., & Berg, A. (2010). The end of an era? The medium- and long-term effects of the global crisis on growth in low-income countries. In IMF working papers 10/205. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Papi, L., Presbitero, A. F., & Zazzaro, A. (2015). IMF lending and banking crises. IMF Economic Review, 63(3), 644–691.

Perry, G. (2009). Beyond lending: How multilateral banks can help developing countries manage volatility. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Robins, J. M. (2002). Comment on covariance adjustment in randomized experiments and observational studies. Statistical Science, 17(3), 309–321.

Roodman, D. (2006). An index of donor performance. Center for Global Development, working paper no 67 (revised in 2012).

Rosenbaum, P. R. (1987). Sensitivity analysis for certain permutation inferences in matched observational studies. Biometrika, 74, 13–26.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55.

Steinwand, M. C. (2015). Compete or coordinate? Aid fragmentation and lead donorship. International Organization, 69(2), 443.

Steinwand, M. C., & Stone, R. W. (2008). The International Monetary Fund: A review of the recent evidence. The Review of International Organizations, 3(2), 123–149.

Stubbs, T. H., Kentikelenis, A. E., & King, L. P. (2016). Catalyzing aid? The IMF and donor behavior in aid allocation. World Development, 78, 511–528.

Thiele, R., Nunnenkamp, P., & Dreher, A. (2007). Do donors target aid in line with the millennium development goals? A sector perspective of aid allocation. Review of World Economics, 143(4), 596–630.

White, H., & McGillivray, M. (1995). How well is aid allocated? Descriptive measures of aid allocation: A survey of methodology and results. Development and Change, 26(1), 163–183.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank two anonymous referees, Axel Dreher, Chris Lane, Catherine Pattillo, Olaf Unteroberdoerster, Marco Arena, Wendell Daal, Ermal Hitaj, Mumtaz Hussain, Paulo Lopez, Henry Moone, Nkunde Mwase, Saad Quayyum, Frank Dong Wu, seminar participants at the IMF, and OECD colleagues Brenda Killen, Elena Bernaldo de Quirós, Olivier Bouret, Andrzej Suchodolski for very helpful comments and suggestions. Merceditas San Pedro-Pribram, Liz Baxter, and Kathryn Norris provided excellent editorial assistance. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bal Gündüz, Y., Crystallin, M. Do IMF programs catalyze donor assistance to low-income countries?. Rev Int Organ 13, 359–393 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-017-9280-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-017-9280-5

Keywords

- IMF-supported programs

- Official development assistance (ODA)

- Catalytic impact

- Low-income countries (LICs)

- Propensity score matching

- Aid allocation

- Aid coordination

- Bilateral aid

- Multilateral aid