Abstract

We explored associations between residential preferences and sociodemographic characteristics, the concordance between current neighborhood characteristics and residential preferences, and heterogeneity in concordance by income and race/ethnicity. Data came from a cross-sectional phone and mail survey of 3668 residents of New York City, Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles, St. Paul, and Winston Salem in 2011–12. Scales characterized residential preferences and neighborhood characteristics. Stronger preferences were associated with being older, female, non-White/non-Hispanic, and lower education. There was significant positive but weak concordance between current neighborhood characteristics and residential preferences (after controlling sociodemographic characteristics). Concordance was stronger for persons with higher income and for Whites, suggesting that residential self-selection effects are strongest for populations that are more advantaged.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Understanding environmental influences on walking—review and research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):67–76.

Van Cauwenberg J, Van Holle V, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Dyck D, Deforche B. Neighborhood walkability and health outcomes among older adults: the mediating role of physical activity. Health Place. 2016;37:16–25.

Guo M, O'Connor Duffany K, Shebl FM, Santilli A, Keene DE. The effects of length of residence and exposure to violence on perceptions of neighborhood safety in an urban sample. J Urban Health. 2018;95(2):245–54.

Perchoux C, Kestens Y, Brondeel R, Chaix B. Accounting for the daily locations visited in the study of the built environment correlates of recreational walking (the RECORD Cohort Study). Prev Med. 2015;81:142–9.

Chaix B, Simon C, Charreire H, et al. The environmental correlates of overall and neighborhood based recreational walking (a cross-sectional analysis of the RECORD Study). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:14.

Ding C, Wang DG, Liu C, Zhang Y, Yang JW. Exploring the influence of built environment on travel mode choice considering the mediating effects of car ownership and travel distance. Transp Res A-Pol Prac. 2017;100:65–80.

Moore LV, Roux AVD, Franco M. Measuring Availability of Healthy Foods: Agreement Between Directly Measured and Self-reported Data. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(10):1037–44.

Zick CD, Smith KR, Fan JX, Brown BB, Yamada I, Kowaleski-Jones L. Running to the Store? The relationship between neighborhood environments and the risk of obesity. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1493–500.

Mackenbach JD, Rutter H, Compernolle S, et al. Obesogenic environments: a systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:15.

Yu R, Wong M, Woo J. Perceptions of neighborhood environment, sense of community, and self-rated health: an age-friendly city project in Hong Kong. J Urban Health. 2019;96(2):276–88.

Chaix B, Billaudeau N, Thomas F, Havard S, Evans D, Kestens Y, et al. Neighborhood effects on health correcting bias from neighborhood effects on participation. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):18–26.

Diez Roux AV. Moving beyond speculation quantifying biases in neighborhood health effects research. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):40–1.

Oakes JM. Commentary: Advancing neighbourhood-effects research—selection, inferential support, and structural confounding. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(3):643–7.

Ewing R, Cervero R. Travel and the built environment. J Am Plann Assoc. 2010;76(3):265–94.

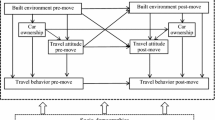

Mokhtarian PL, Cao XY. Examining the impacts of residential self-selection on travel behavior: a focus on methodologies. Transport Res B-Meth. 2008;42(3):204–28.

Mokhtarian PL, van Herick D. Quantifying residential self-selection effects: a review of methods and findings from applications of propensity score and sample selection approaches. J Transp Land Use. 2016;9(1):9–28.

Kroes EP, Sheldon RJ. Stated preference methods: an introduction. J Transp Econ Pol. 1988; 22(1):11-25.

Bennear L, Stavins RN, Wagner AF. Using revealed preferences to infer environmental benefits: evidence from recreational fishing licenses. J Regul Econ. 2005;28(2):157–79.

Frank LD, Saelens BE, Powell KE, Chapman JE. Stepping towards causation: do built environments or neighborhood and travel preferences explain physical activity, driving, and obesity? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(9):1898–914.

Cao XY, Mokhtarian PL, Handy SL. Examining the impacts of residential self-selection on travel behaviour: a focus on empirical findings. Transp Rev. 2009;29(3):359–95.

Howell NA, Farber S, Widener MJ, Allen J, Booth GL. Association between residential self-selection and non-residential built environment exposures. Health Place. 2018;54:149–54.

Heinen E, Wee Bv, Panter J, Mackett R, Ogilvie D. Residential self‐selection in quasi‐experimental and natural experimental studies. J Transp Econ Pol. 2018;11(1): 939-959.

Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Guilkey DK, Jacobs DR, Popkin BM. Environment and physical activity dynamics: the role of residential self-selection. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2011;12(1):54–60.

Boone-Heinonen J, Guilkey DK, Evenson KR, Gordon-Larsen P. Residential self-selection bias in the estimation of built environment effects on physical activity between adolescence and young adulthood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:11.

Søgaard AJ, Selmer R, Bjertness E, Thelle D. The Oslo health study: the impact of self-selection in a large, population-based survey. Int J Equity Health. 2004;3(1):3.

Kitamura R, Mokhtarian PL, Laidet L. A micro-analysis of land use and travel in five neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area. Transportation. 1997;24(2):125–58.

Cao XY, Handy SL, Mokhtarian PL. The influences of the built environment and residential self-selection on pedestrian behavior: evidence from Austin, TX. Transportation. 2006;33(1):1–20.

Bagley MN, Mokhtarian PL. The impact of residential neighborhood type on travel behavior: a structural equations modeling approach. Ann Regional Sci. 2002;36(2):279–97.

Cao XY, Mokhtarian PL, Handy SL. The relationship between the built environment and nonwork travel: a case study of Northern California. Transp Res A-Pol Prac. 2009;43(5):548–59.

Chatman DG. Residential choice, the built environment, and nonwork travel: evidence using new data and methods. Environ Plann A. 2009;41(5):1072–89.

Bhat CR, Eluru N. A copula-based approach to accommodate residential self-selection effects in travel behavior modeling. Transp Res B-Meth. 2009;43(7):749–65.

Vance C, Hedel R. The impact of urban form on automobile travel: disentangling causation from correlation. Transportation. 2007;34(5):575–88.

Khattak AJ, Rodriguez D. Travel behavior in neo-traditional neighborhood developments: a case study in USA. Transp Res A-Pol Prac. 2005;39(6):481–500.

Zick CD, Hanson H, Fan JX, et al. Re-visiting the relationship between neighbourhood environment and BMI: an instrumental variables approach to correcting for residential selection bias. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:10.

Laham ML, Noland RB. Nonwork trips associated with transit-oriented development. Transp Res Rec. 2017;2606:46–53.

Galster G, Hedman L. Measuring neighbourhood effects non-experimentally: how much do alternative methods matter? Hous Stud. 2013;28(3):473–98.

Hedman L, Galster G. Neighbourhood income sorting and the effects of neighbourhood income mix on income: a holistic empirical exploration. Urban Stud. 2013;50(1):107–27.

Jarass J, Scheiner J. Residential self-selection and travel mode use in a new inner-city development neighbourhood in Berlin. J Transp Geogr. 2018;70:68–77.

Baar J, Romppel M, Igel U, Brahler E, Grande G. The independent relations of both residential self-selection and the environment to physical activity. Int J Environ Health Res. 2015;25(3):288–98.

Cao XY. Examining the impacts of neighborhood design and residential self-selection on active travel: a methodological assessment. Urban Geography. 2015;36(2):236–55.

Berry TR, Spence JC, Blanchard CM, Cutumisu N, Edwards J, Selfridge G. A longitudinal and cross-sectional examination of the relationship between reasons for choosing a neighbourhood, physical activity and body mass index. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:11.

Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Conway TL, Slymen DJ, Cain KL, et al. Neighborhood built environment and income: examining multiple health outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(7):1285–93.

Cao XY, Mokhtarian PL, Handy SL. Cross-sectional and quasi-panel explorations of the connection between the built environment and auto ownership. Environ Plann A. 2007;39(4):830–47.

Handy S, Cao XY, Mokhtarian PL. Self-selection in the relationship between the built environment and walking—empirical evidence from northern California. J Am Plann Assoc. 2006;72(1):55–74.

Lund H. Reasons for living in a transit-oriented development, and associated transit use. Journal of the American Planning Association. Sum. 2006;72(3):357–66.

Aditjandra PT, Cao XY, Mulley C. Understanding neighbourhood design impact on travel behaviour: an application of structural equations model to a British metropolitan data. Transp Rest A-Pol Pract. 2012;46(1):22–32.

Ewing R, Hamidi S, Grace JB. Compact development and VMT-Environmental determinism, self-selection, or some of both? Environ Plann B-Plann Design. 2016;43(4):737–55.

Mackenbach JD, de Pinho MGM, Faber E, et al. Exploring the cross-sectional association between outdoor recreational facilities and leisure-time physical activity: the role of usage and residential self-selection. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:11.

Van Dyck D, Cardon G, Deforche B, Owen N, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Relationships between neighborhood walkability and adults' physical activity: how important is residential self-selection? Health Place. 2011;17(4):1011–4.

Schwanen T, Mokhtarian PL. The extent and determinants of dissonance between actual and preferred residential neighborhood type. Environ Plann B-Plann Design. 2004;31(5):759–84.

Tung EL, Cagney KA, Peek ME, Chin MH. Spatial context and health inequity: reconfiguring race, place, and poverty. J Urban Health. 2017;94(6):757–63.

Vaughan CA, Cohen DA, Han B. How do racial/ethnic groups differ in their use of neighborhood parks? Findings from the National Study of Neighborhood Parks. J Urban Health. 2018;95(5):739–49.

Do DP, Frank R, Iceland J. Black-white metropolitan segregation and self-rated health: investigating the role of neighborhood poverty. Soc Sci Med. 2017;187:85–92.

Cho GH, Rodriguez DA. The influence of residential dissonance on physical activity and walking: evidence from the Montgomery County, MD, and Twin Cities, MN, areas. J Transp Geography. 2014;41:259–67.

De Vos J, Derudder B, Van Acker V, Witlox F. Reducing car use: changing attitudes or relocating? The influence of residential dissonance on travel behavior. J Transp Geography. 2012;22:1–9.

Schwanen T, Mokhtarian PL. What if you live in the wrong neighborhood? The impact of residential neighborhood type dissonance on distance traveled. Transport Res D-Transport Environ. 2005;10(2):127–51.

Schwanen T, Mokhtarian PL. What affects commute mode choice: neighborhood physical structure or preferences toward neighborhoods? J Transp Geography. 2005;13(1):83–99.

Kamruzzaman M, Baker D, Washington S, Turrell G. Residential dissonance and mode choice. J Transp Geography. 2013;33:12–28.

Mujahid MS, Roux AVD, Morenoff JD, Raghunathan T. Assessing the measurement properties of neighborhood scales: from psychometrics to ecometrics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(8):858–67.

Echeverria SE, Diez-Roux AV, Link BG. Reliability of self-reported neighborhood characteristics. J Urban Health. 2004;81(4):682–701.

Liao FH, Farber S, Ewing R. Compact development and preference heterogeneity in residential location choice behaviour: a latent class analysis. Urban Stud. 2015;52(2):314–37.

Van Acker V, Witlox F. Commuting trips within tours: how is commuting related to land use? Transportation. 2011;38(3):465–86.

Cools M, Moons E, Janssens B, Wets G. Shifting towards environment-friendly modes: profiling travelers using Q-methodology. Transportation. 2009;36(4):437–53.

Naess P. Tempest in a teapot: The exaggerated problem of transport-related residential self-selection as a source of error in empirical studies. J Transp Land Use. 2014;7(3):57–79.

Wang DG, Li SM. Socio-economic differentials and stated housing preferences in Guangzhou, China. Hab Int. 2006;30(2):305–26.

Naess P. Residential location affects travel behavior—but how and why? The case of Copenhagen Metropolitan area. Prog Plann. 2005;63:161.

Charles CZ. The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Ann Rev Sociol. 2003;29:167–207.

Sigelman L, Henig JR. Crossing the great divide—race and preferences for living in the city versus the suburbs. Urban Affairs Rev. 2001;37(1):3–18.

Clark WAV. Residential preferences and residential choices in a multiethnic context. Demography. 1992;29(3):451–66.

Havekes E, Bader M, Krysan M. Realizing racial and ethnic neighborhood preferences? exploring the mismatches between what people want, where they search, and where they live. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2016;35(1):101–26.

Sirgy MJ, Grzeskowiak S, Su C. Explaining housing preference and choice: the role of self-congruity and functional congruity. J Hous Built Environ. 2005;20(4):329–47.

Schwanen T, Mokhtarian PL. Attitudes toward travel and land use and choice of residential neighborhood type: evidence from the San Francisco bay area. Hous Policy Debate. 2007;18(1):171–207.

Bagley MN, Mokhtarian PL. The role of lifestyle and attitudinal characteristics in residential neighborhood choice. In: Ceder A. (ed) Transportation and traffic theory: Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Transportation and Traffic Theory. Oxford: Pergamon Press Ltd. 1999: pp 735–758.

Lin T, Wang DG, Guan XD. The built environment, travel attitude, and travel behavior: residential self-selection or residential determination? J Transp Geography. 2017;65:111–22.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [grant numbers R01 HL 131610 and R01 HL071759] and NIH National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [R01 MD012621].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Auchincloss, A.H., Rodriguez, D.A. et al. Determinants of Residential Preferences Related to Built and Social Environments and Concordance between Neighborhood Characteristics and Preferences. J Urban Health 97, 62–77 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00397-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00397-7