Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to investigate the longitudinal positron emission tomography (PET) metabolic changes in the elderly.

Procedures

Nineteen nondemented subjects (mean Mini-Mental Status Examination 29.4 ± 0.7 SD) underwent two detailed neuropsychological evaluations and resting 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-d-glucose (FDG)-PET scan (interval 21.7 ± 3.7 months), baseline structural 3T magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, and apolipoprotein E4 genotyping. Cortical PET metabolic changes were analyzed in 3-D using the cortical pattern matching technique.

Results

Baseline vs. follow-up whole-group comparison revealed significant metabolic decline bilaterally in the posterior temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes and the left lateral frontal cortex. The declining group demonstrated 10–15% decline in bilateral posterior cingulate/precuneus, posterior temporal, parietal, and occipital cortices. The cognitively stable group showed 2.5–5% similarly distributed decline. ApoE4-positive individuals underwent 5–15% metabolic decline in the posterior association cortices.

Conclusions

Using 3-D surface-based MR-guided FDG-PET mapping, significant metabolic changes were seen in five posterior and the left lateral frontal regions. The changes were more pronounced for the declining relative to the cognitively stable group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clinical progression to dementia may be viewed as a continuum in which cognitively normal subjects gradually decline over time until they reach the functionally and cognitively compromised state of dementia. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia worldwide. Given that only symptomatic AD therapy is currently available, researchers are focused on the development of disease-modifying agents and on studying the preclinical trajectory of those predestined to develop AD. As therapeutic disease reversal seems unlikely in the near future, disease biomarkers and innovative imaging strategies are required to show the precursor dementia changes in the human brain. These developments are crucial for a better understanding of the disease process and for early diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment [1–3].

Functional neuroimaging offers the opportunity to demonstrate brain dysfunction in the earliest stages of neurodegeneration. Positron emission tomography (PET) is well established as a sensitive and a specific prognostic tool for future cognitive decline [4–6]. Subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who later convert to AD are consistently reported to show temporoparietal and posterior cingulate hypometabolic changes [5, 7–11]. A pre-MCI hypometabolic pattern in the entorhinal cortex has likewise been reported in cognitively normal elderly [12].

In the current study, we used longitudinal cognitive and 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-d-glucose (FDG)-PET data from 19 elderly subjects who did not meet National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-AD and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria for dementia at baseline. We hypothesized that those who decline cognitively would show changes over time in PET metabolic activity in the medial and lateral temporal, lateral parietal, and posterior cingulate/precuneal cortical areas. In addition, we used a method to align PET data across subjects that increases statistical power by controlling for the large intersubject variations in cortical surface shape and gyral patterning. Each subject's PET data were projected onto their 3-D hemispheric surface models from the corresponding co-registered magnetic resonance image while using surface landmarks to guide accurate imaging data integration. In the resulting surface projection maps, functional deficits can be localized with respect to gyral anatomy, which is not resolved in standard functional image averaging methods.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We analyzed data from 19 nondemented subjects, recruited through media advertisement and physician referrals. All subjects provided informed consent for participation. The analyses were approved by University of California at Los Angeles Institutional Review Board. Subjects between the ages of 50–85 years, who did not have dementia or mild cognitive impairment, were recruited. Criteria for dementia were based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) [12] and NINCDS-ADRDA [13]; criteria for MCI were based upon nondemented subjects either having a clinical evaluation identifying cognitive difficulties greater than expected for age or by performance on a formal neuropsychologic panel (see below), identifying scores falling at least one standard deviation below age-adjusted norms on at least one half of the memory tests. The neuropsychological evaluation consisted of Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (subtests administered: digit span forward and backward, similarities, block design, digit symbol substitution) [13], Buschke Selective Reminding test [14], Wechsler Memory Scale-III (subtests administered: Logical memory I and II, paired associates) [15], Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure test-copy and reproduction [16], Benton Visual Retention Test [17], Boston Naming test [18], Controlled Oral Word Association test [19], Trailmaking A and B [20], Wisconsin Card Sorting test [21], and Stroop test A, B, and C [22, 23]. Subjects were classified as having undergone cognitive decline if they went from having no neuropsychologic test score falling 1.5 SD below the age- and education-adjusted norms at baseline to one or more scores falling below that level at 2-year follow-up without meeting criteria for dementia (e.g., preserved activities of daily living) or if they went from having one or more scores in that range at baseline without dementia to meeting criteria for dementia at the 2-year follow-up. The 1.5 SD threshold was selected in assessing meaningful decline because of its use in many prior longitudinal PET studies as a criterion for cognitive impairment [4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 25].

All subjects received a 3 T baseline structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, baseline and follow-up FDG-PET scans, genetic screen for the apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele (ApoE4), and detailed clinical, neuropsychological, and psychiatric evaluation documenting the absence of dementia or another neurological or psychiatric disorder. The average time to follow-up was 21.7 ± 3.7 months (range 16.3–31.9 months).

Structural MRI Acquisition and Processing

Baseline double-echo fast-spin echo structural MRI data were acquired on a 3 T General Electric Signa magnet using the following protocol: time to repetition TR = 6,000 ms, time to echo TE = 17/85 ms, matrix 256 × 256, 3 mm slice thickness, with 0 gap and 24 cm field of view. Images were first linearly aligned to the ICBM53 average brain template using a nine-parameter transformation [24]. A correction for image intensity inhomogeneities was performed with a regularized tricubic B-spline method [25, 26]. An automated whole-brain mask was created with a software package called Brainsuite, freely available at http://www.loni.ucla.edu/Software/Software_Detail.jsp?software_id=19 [26]. The whole-brain mask was split into two hemispheric masks, and all misclassified tissue (brain vs. nonbrain) was manually corrected. The hemispheric masks were then used for hemisphere extraction, followed by an automated 3-D hemispheric reconstruction [27]. The automated hemispheric reconstruction (extraction) is achieved by continuous deformation of a mesh-like surface to fit a threshold intensity value that best differentiates gray matter from cerebrospinal fluid. The intensity threshold was defined as the MRI signal value that best differentiated cortical cerebrospinal fluid on the outer surface of the brain from the underlying cortical gray matter. The resulting 3-D hemispheric reconstruction represents a high-resolution mesh of 131,072 surface triangles spanning 65,536 surface points. Thirty-six individual sulcal lines were manually drawn on the medial and lateral hemispheric surfaces using an in-house validated sulcal delineation protocol [28, 29]. On the lateral brain surface, these included: the Sylvian fissure; central, pre-central, and post-central sulci; superior temporal sulcus (STS) main body; STS ascending branch; STS posterior branch; primary and secondary intermediate sulci; inferior temporal, superior and inferior frontal, intraparietal, transverse occipital, olfactory, occipito-temporal, and collateral sulci. On the medial surface, these included: the callosal sulcus, the inferior callosal outline, the paracentral sulcus, anterior and posterior cingulate sulci, the outer segment of a double parallel cingulate sulcus, the superior and inferior rostral sulci, the parieto-occipital sulcus, the anterior and posterior calcarine sulci, and the subparietal sulcus. In addition to contouring the major sulci, a set of six midline landmark curves bordering the longitudinal fissure was outlined in each hemisphere to establish hemispheric gyral limits. Ambiguities in sulcal determination were resolved with the help of the individual's spatially registered 3-D MRI volume simultaneously visualized in three planes (axial, coronal, and sagittal). The hemispheric surfaces and the sulcal maps were mathematically flattened into a 2-D plane. The left and right sulcal maps for all 19 subjects were used to create a study-specific average sulcal map, and the deformation fields needed to transform each individual sulcal map into the study average sulcal map were recorded. The flattened cortical surfaces were then warped following the individual deformation fields resulting from the transformation needed for the alignment of the individual sulcal lines to the group average. 3-D parametric mesh hemispheric models were created. This procedure, termed cortical pattern matching [30], removes as much as possible the confounding effects of cross-subject anatomical variance, whereas it empowers detection of disease effects. The computational matching of sulci avoids destructive cancellation of features that results from direct averaging of images together and ensures that common features are reinforced in the group average and appear in their group mean anatomic location. Associated local measures of gray matter density or in this case PET signal intensity may be convected along with these warps and plotted on the average cortex, prior to statistical analysis.

FDG-PET Data Acquisition and Processing

Baseline and follow-up resting FDG-PET data were acquired 40 min after intravenous injection of 370 MBq FDG on a CTI/Siemens HR+ scanner (Siemens, Hoffman Estates, IL, USA). Scans were acquired parallel to the canthomeatal line. The PET data were first normalized to the whole brain global mean. Each subject's baseline and follow-up PET scans were rigidly aligned to the respective International Consortium for Brain Mappin (ICBM) aligned baseline MRI scan. To assign FDG-PET signals to vertices on the cortical surface, it is advantageous to sample the data using a small spherical kernel. Kernel sizes in the range 10–15 mm give average surface values in good agreement with conventional region of interest measures from each lobe of the brain (unpublished data, [31]). In the present study, we used a 15-mm kernel to map the individual FDG-PET activity onto each surface vertex of the individual hemispheric models. As described above, we convected the FDG-PET data along the warping deformations computed in the cortical pattern-matching procedure, assuring as accurate as possible between-subjects anatomic correspondence in the final group average maps. Average baseline and follow-up 3-D PET maps were computed. We used linear regression models to regress PET intensity at each surface point against scanning time point (e.g., baseline vs. follow-up) [32]. These maps were corrected for multiple comparisons using permutation testing on the area of the statistical maps thresholded at p < 0.01 [30]. Quantitative ratio and percent change maps for baseline vs. follow-up changes were created for decliners, nondecliners, and ApoE4 carriers and noncarriers [33].

We also used two region-of-interest (ROI) approaches to validate our findings. We first applied an automated ROI probabilistic atlas-based approach to obtain mean lobar PET activity. This approach, described in detail previously [34], is similar to a traditional voxel-based ROI analysis. In addition, we also used manually created lobar ROIs to derive mean lobar PET activity from the 3-D PET hemispheric models.

Statistical Methods

We used two-tailed independent sample Student's t tests for continuous and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables as we compared age, gender, ApoE4 genotype, and Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) at baseline and follow-up between future decliners vs. nondecliners at baseline.

The 3-D maps showing the significance of changes between baseline and follow-up PET scans were corrected for multiple comparisons using the permutation method [35]. This technique controls for spurious associations by computing the probability that the statistically significant (below a predefined threshold) regions in any given statistical map would occur by chance alone. The algorithm randomly reassigns group membership to the participating subjects in each statistical comparison, while keeping the total number of subjects per group the same, and recomputes the p value at each vertex at each iteration. We used 100,000 permutations to compute the corrected statistical significance for the hemispheric maps as well as for the individual lobes. The latter was accomplished by using a lobar mask to narrow the region of interest for permutation testing. The lobar masks included the whole lobes inclusive of their medial, lateral, and inferior surfaces as appropriate. The voxel-level threshold for all permutation tests was set at p < 0.01 [30]. The ROI measures were compared using paired and unpaired Student's t test as appropriate.

Results

Demographic, Genetic, and Cognitive Comparisons

Demographic data are listed in Table 1. At baseline, the study group consisted of 19 cognitively intact elderly subjects. At follow-up, four subjects met the criteria for cognitive decline as outlined in the “Materials and Methods” section. The decliners did not show a change in mean MMSE score from baseline to follow-up, while nondecliners showed an interim decline of 0.6 points from 29.3 to 28.7 points.

Whole-Group 3-D Baseline PET vs. Follow-up PET Comparisons

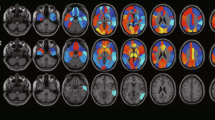

We first compared baseline PET vs. follow-up PET activity for the whole group (Fig. 1). We observed significantly lower metabolic activity in the bilateral posterior cingulate, posterior temporal, inferior parietal, and temporo-parieto-occipital cortices, as well as the precuneus and posterior middle and inferior frontal gyrus on the left. After correction for multiple comparisons using a threshold of p < 0.01, the global p value for the left hemisphere was trend-significant (p = 0.057). The right did not reach global significance at this threshold (p = 0.22). After restricting the permutation regions to specific lobes, statistically significant differences were present in all three lobes of interest on the left (left parietal lobe p = 0.011, left temporal lobe p = 0.049, and left occipital lobe p = 0.04), while only the occipital lobe showed significant difference on the right (p = 0.048).

Whole-Group ROI Baseline PET vs. Follow-up PET Comparisons

Using the probabilistic atlas-based automated ROI method, only the parietal lobes showed trend-significant change from baseline and follow-up across the full sample (p = 0.08). Using the ROI-derived mean lobar activity from the 3-D PET models, significant baseline-to-follow-up change was seen for the left frontal (p = 0.039), left temporal (p = 0.015), left parietal (p = 0.001), right parietal (p = 0.006), and right occipital (p = 0.026) lobes. A trend for significance was observed for the left occipital lobe (p = 0.06). No statistically significant differences were observed with either method between decliners and nondecliners or between ApoE4-positive and ApoE4-negative subjects at baseline or in follow-up.

Within-Group Longitudinal Changes in Metabolic Activity

Figure 2 shows the percent change in PET metabolic activity in the cognitively stable group (top) and the declining group (bottom). Relative to baseline FDG uptake, decliners had 5–15% less uptake in the posterior association cortices including the posterior cingulate, precuneus, lateral parietal, posterior temporal, and occipital regions and 2.5–5% decline in the entorhinal/parahippocampal, inferior temporal, and lateral frontal regions in follow-up (Fig. 2, bottom). Nondecliners demonstrated a similar posterior predominant pattern, but the changes were not as pronounced (2.5–5%). The temporo-parieto-occipital junction showed the most pronounced FDG uptake differences between baseline and follow-up in both groups.

Five subjects were heterozygous for ApoE4, while 14 were ApoE3 homozygous. The ApoE4 group had predominantly posterior interval changes encompassing the lateral and medial temporal and occipital, and the lateral parietal lobes. Quantitatively, the decline in mean FDG uptake varied between 2% and 15%. Largest differences were observed in the lateral temporo-occipital and occipital association cortices (Fig. 3, bottom). The ApoE3 group showed decline over the interval in FDG uptake in a more extensive region of the cortex. The greatest decline (5–10%) was observed in the posterior cingulate, precuneus, and temporo-occipital association cortices bilaterally as well as the left inferior frontal gyrus (Fig. 3, top).

Discussion

Neurodegenerative disorders are a large group of diseases characterized by progressive regionally specific pathologic changes. The most common neurodegenerative disorder among the elderly is AD. AD typically presents with cognitive decline, most notably in verbal and visual memory and in the visuospatial domain, as a result of progressive deterioration of the posterior association cortices and the hippocampal formations.

Unlike brain atrophy, PET metabolic changes are not considered to be a normal part of aging. Our study included 19 cognitively normal subjects who were initially evaluated and re-evaluated approximately 2 years later with cognitive examinations and PET imaging. The longitudinal changes localized to the lateral posterior association cortices, the posterior cingulate and precuneus bilaterally, and the left middle and inferior frontal gyrus. While both the decliners and nondecliners experienced relative metabolic decline, the former demonstrated greater changes in the areas discussed above (e.g., 5–15% vs. 2.5–5%). ApoE4 carriers showed greater metabolic decline in posterior brain regions, as is typically seen in patients with early AD. The quantitative differences between decliners and nondecliners and ApoE4 carriers and noncarriers did not however reach statistical significance likely because of limitations imposed by our low sample size.

So far, several research groups have reported that metabolic decline in the temporal [5, 7, 8, 36] and/or parietal [5, 10, 36] areas is predictive of clinical diagnosis of AD within a follow-up period ranging from 12 to 36 months on average. Posterior hypometabolism in ApoE4 carriers relative to noncarriers was also noted in several studies [10, 37–39]. One group conducted 3-year follow-up of cognitively normal individuals and reported entorhinal hypometabolism in normals that converted to MCI in follow-up and newly developed hippocampal and lateral and inferior temporal hypometabolism in follow-up (e.g., in the MCI stage) [12]. By using a sensitive computational anatomy technique to map progressive metabolic changes, our study extends these findings by reporting more widespread progressive changes encompassing the association cortices of the posterior temporal, superior, and inferior lateral parietal, occipital, precuneus, and posterior cingulate. The lateral but not the medial cortical changes also showed linkage with the presence of an ApoE4 allele in the present study.

A major strength of this study is its prospective longitudinal design coupled with a sensitive surface mapping technique well suited for assessing intra-individual longitudinal change. Surface feature-guided cortical alignment improves the comparison of corresponding cortical areas between individuals and results in greater statistical power to detect disease-induced changes. Similar to several other longitudinal studies in normal elderly and MCI [8, 10, 11, 36], we normalized the individual average PET intensity to the group average global brain intensity, which may lead to underestimation of the regional changes [40]. The diagnostic criteria for cognitive decline used in the present study are similar to those used in some [5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 36] but not all [12] longitudinal PET studies of cognitively normal elderly and mild cognitive impairment subjects.

Conclusions

Our advanced technique based on 3-D surface-based MR-guided FDG-PET mapping helped us detect significant interim metabolic changes in five posterior and the left lateral frontal regions in cognitively normal elderly. These areas are known to be affected early by AD pathology. Head-to-head comparison of ROI analyses without and with cortical pattern matching demonstrates improved sensitivity to metabolic changes after explicit matching of homologous cortical areas. This results from minimizing cortical mismatch due to inter-individual differences in cortical morphology. Using advanced surface-based techniques to map progressive metabolic cortical changes in subjects with neurodegenerative diseases may help the identification of subtle changes which may be potentially useful for early and eventually pre-symptomatic detection, diagnosis, and treatment.

References

Monien BH, Apostolova LG, Bitan G (2006) Early diagnostics and therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease—how early can we get there? Expert Rev Neurother 6:1293–1306

Apostolova LG, Thompson PM (2007) Brain mapping as a tool to study neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics 4:387–400

Apostolova LG, Thompson PM (2008) Mapping progressive brain structural changes in early Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia 46:1597–1612

Silverman DHS, Thompson PM (2006) Structural and functional neuroimaging: focussing on mild cognitive impairment. Applied Neurology 10-24

Drzezga A, Grimmer T, Riemenschneider M et al (2005) Prediction of individual clinical outcome in MCI by means of genetic assessment and (18)F-FDG-PET. J Nucl Med 46:1625–1632

Silverman DH, Small GW, Chang CY et al (2001) Positron emission tomography in evaluation of dementia: regional brain metabolism and long-term outcome. Jama 286:2120–2127

Arnaiz E, Jelic V, Almkvist O et al (2001) Impaired cerebral glucose metabolism and cognitive functioning predict deterioration in mild cognitive impairment. NeuroReport 12:851–855

Chetelat G, Desgranges B, de la Sayette V et al (2003) Mild cognitive impairment: can FDG-PET predict who is to rapidly convert to Alzheimer's disease? Neurology 60:1374–1377

Drzezga A, Lautenschlager N, Siebner H et al (2003) Cerebral metabolic changes accompanying conversion of mild cognitive impairment into Alzheimer's disease: a PET follow-up study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:1104–1113

Mosconi L, Perani D, Sorbi S et al (2004) MCI conversion to dementia and the APOE genotype: a prediction study with FDG-PET. Neurology 63:2332–2340

Mosconi L, Tsui WH, Pupi A et al (2007) (18)F-FDG-PET database of longitudinally confirmed healthy elderly individuals improves detection of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Nucl Med 48:1129–1134

de Leon MJ, Convit A, Wolf OT et al (2001) Prediction of cognitive decline in normal elderly subjects with 2-[(18)F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose/poitron-emission tomography (FDG/PET). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:10966–10971

Wechsler D (1981) WAIS-R manual. The Psychological Corporation, New York

Buschke H (1984) Cued recall in amnesia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 6:433–440

Wechsler D (1987) Wechsler memory scale—revised. The Psycholocical Corporation, San Antonio

Osterrieth PA (1944) Le test de copie d'une figure complexe. Archieves de Psychologie 30:206–356

Benton A (1991) Benton visual retention test. The Psychological Corporation, New York

Kaplan EF, Goodgalss H, Weintraub S (1983) The Boston Naming Test. Lea&Febiger, Philadelphia

Benton AL, Hamsher K (1989) Multilingual apahasia examination. AJA Associates, Iowa City

Kelland DZ, Lewis R, Gurevitch D (1992) Evaluation of the Repeatable Cognitive-Perceptual-Motor battery: reliability, validity and sensitivity to diazepam. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 14:65 abstract

Berg L (1948) A simple objective treatment for measuring flexibility in thinking. J Gen Psychol 39:15–22

Jensen AR, Rohwer WD (1966) The Stroop Color-Word Test: a review. Acta Psychol 25:36–93

Stroop JR (1935) Studies in interference of serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 18:643–662

Collins DL, Neelin P, Peters TM et al (1994) Automatic 3-D intersubject registration of MR volumetric data in standardized Talairach space. J Comput Assist Tomogr 18:192–205

Shattuck DW, Sandor-Leahy SR, Schaper KA et al (2001) Magnetic resonance image tissue classification using a partial volume model. Neuroimage 13:856–876

Shattuck DW, Leahy RM (2002) BrainSuite: an automated cortical surface identification tool. Med Image Anal 6:129–142

MacDonald D, Avis D, Evans A (1994) Multiple surface identification and matching in magnetic resonance imaging. Proc SPIE:160-169

Hayashi KM, T.P., Mega MS, Zoumalan CI. Medial hemispheric surface gyral pattern delineation in 3-D: surface curve protocol. Available at: http://users.loni.ucla.edu/~khayashi/Public/medial_surface/ [online]. Available.

Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Mega MS, Zoumalan CI, Lindshield C, Rex DE. Gyral pattern delineation in 3-D: surface curve protocol. Available at: www.loni.ucla.edu/∼esowell/new_sulcvar.html [online]. Available.

Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, de Zubicaray G et al (2003) Dynamics of gray matter loss in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 23:994–1005

Protas H, Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, et al. (2005) Cortical brain surface mapping for studying partial volume effects in brain FG-PET images. In: 52nd Annual Meeting of the Society for Nuclear Medicine; Toronto, Canada

Braskie MN, Klunder AD, Hayashi KM et al (2009) Plaque and tangle imaging and cognition in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging (in press). doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.09.012

Apostolova LG, Steiner CA, Akopyan GG et al (2007) Three-dimensional gray matter atrophy mapping in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 64:1489–1495

Mega MS, Dinov ID, Mazziotta JC et al (2005) Automated brain tissue assessment in the elderly and demented population: construction and validation of a sub-volume probabilistic brain atlas. Neuroimage 26:1009–1018

Thompson PM, Lee AD, Dutton RA et al (2005) Abnormal cortical complexity and thickness profiles mapped in Williams syndrome. J Neurosci 25:4146–4158

Chetelat G, Eustache F, Viader F et al (2005) FDG-PET measurement is more accurate than neuropsychological assessments to predict global cognitive deterioration in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurocase 11:14–25

Small GW, Ercoli LM, Silverman DH et al (2000) Cerebral metabolic and cognitive decline in persons at genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6037–6042

Small GW, Mazziotta JC, Collins MT et al (1995) Apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and cerebral glucose metabolism in relatives at risk for familial Alzheimer disease. Jama 273:942–947

Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Yun LS et al (1996) Preclinical evidence of Alzheimer's disease in persons homozygous for the epsilon 4 allele for apolipoprotein E. N Engl J Med 334:752–758

Mevel K, Desgranges B, Baron JC et al (2007) Detecting hippocampal hypometabolism in Mild Cognitive Impairment using automatic voxel-based approaches. Neuroimage 37:18–25

Acknowledgments

This study was generously supported by NIA K23 AG026803 (jointly sponsored by NIA, AFAR, The John A. Hartford Foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, the Starr Foundation, and an anonymous donor; to LGA), NIA P50 AG16570 (to JLC, LGA and PMT); NIBIB EB01651, NLM LM05639, NCRR RR019771 (to PMT); NIH/NIMH R01 MH071940, NIH/NCRR P41 RR013642 and NIH U54 RR021813 (to AWT and PMT); NIH PO1-AG024831, AG 13308, P50 AG16570, MH/AG58156, MH52453, AG10123, MO1-RR00865 (to GWS), the Department of Energy (DOE contract DE-FC03-87-ER60615), General Clinical Research Centers Program, the Rotary CART Fund; the Alzheimer's Association; the Fran and Ray Stark Foundation Fund for Alzheimer's Disease Research; the Ahmanson Foundation; the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation; the Lovelace Foundation, the Judith Olenick Elgart Fund for Research on Brain Aging, the John D. French Foundation for Alzheimer's Research, and the Tamkin Foundation (to GWS).

Financial Disclosure

The University of California, Los Angeles, owns a US patent (6,274,119) entitled “Methods for Labeling b-Amyloid Plaques and Neurofibrillary Tangles,” that uses the approach outlined in this article which has been licensed to Siemens. Dr. Small is among the inventors, has received royalties, and will receive royalties on future sales. Dr. Small reports having served as a consultant and/or having received lecture fees from Abbott, Brainstorming Co., Dakim, Eisai, Forest, Myriad Genetics, Novartis, Ortho-McNeil, Pfizer, Radica, and Siemens. Dr. Small also reports having received stock options from Dakim. These disclosures do not present conflict of interest in respect to the work reported here.

The remaining authors have no disclosures pertaining to the work reported here.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This original article introduces a new powerful technique for analysis of FDG-PET data, representing the first application of PET surface feature-guided analysis to cognitive aging and dementia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Apostolova, L.G., Thompson, P.M., Rogers, S.A. et al. Surface Feature-Guided Mapping of Cerebral Metabolic Changes in Cognitively Normal and Mildly Impaired Elderly. Mol Imaging Biol 12, 218–224 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-009-0247-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-009-0247-7