Abstract

Purpose

According to the guidelines of International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) and National Wilms Tumor Study (NWTS), Wilms tumor with preoperative rupture should be classified as at least stage III. Few clinical reports can be found about preoperative Wilms tumor rupture. The purpose of this study was to investigate our experience on the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of preoperative Wilms tumor rupture.

Methods

Patients with Wilms tumor who underwent treatment according to the NWTS or SIOP protocol from January 2008 to September 2017 in Beijing Children’s Hospital were reviewed retrospectively. The clinical signs of preoperative tumor rupture were acute abdominal pain, and/or fall of hemoglobin. The radiologic signs of preoperative tumor rupture are as follows: (1) retroperitoneal and/or intraperitoneal effusion; (2) acute hemorrhage located in the sub-capsular and/or perirenal space; (3) tumor fracture communicating with peritoneal effusion; (4) bloody ascites. Patients with clinical and radiologic signs of preoperative tumor rupture were selected. Patients having radiologic signs without clinical symptoms were also selected. The clinical data, treatments and outcomes were analyzed. Meanwhile, patients without preoperative Wilms tumor rupture during the same period were collected and analyzed.

Results

565 Patients with Wilms tumor were registered in our hospital. Of these patients, 45 patients were diagnosed with preoperative ruptured Wilms tumor. All preoperative rupture were confirmed at surgery. Spontaneous tumor rupture occurred in 41 patients, the other 4 patients had traumatic history. Of the 45 patients, 41 were classified as stage III, 3 patients with pulmonary metastases were classified as stage IV, and one patient with bilateral tumors were classified as stage V. Of these patients with preoperative tumor rupture at stage III, 30 patients had clinical and radiologic signs of tumor rupture, the other 11 patients had radiologic signs without clinical symptoms. Among the 41 patients at stage III, 13 patients had immediate surgery without preoperative chemotherapy (immediate group), and 28 patients had delayed surgery after preoperative chemotherapy (delayed group). In immediate group, 12 patients had localized rupture, 1 patient underwent emergency surgery because of continuous bleeding. In delayed group, 4 had inferior vena cava tumor embolus (1 thrombus extended to inferior vena cava behind the liver, three thrombi got to the right atrium), 4 crossed the midline with large tumors, 20 had extensive rupture without localization. In immediate group, tumor recurrence and metastasis developed in 2 patients, and no death occurred. In the delayed group, tumor recurrence and metastasis developed in 8 patients, and 7 patients died. During the same period, 41 patients were classified as stage III without preoperative rupture. In the non-ruptured group, tumor recurrence and metastasis developed in 3 patients, and 4 patients died. The median survival time in the ruptured group (both immediate group and delayed group) and non-ruptured group were (85.1 ± 7.5) and (110.3 ± 5.6) months, and the 3-year cumulative survival rates were 75.1% and 89.6%, respectively. The overall survival rate between the ruptured and non-ruptured groups showed no statistic difference (P = 0.256). However, there was significant difference in recurrence or metastasis rate between the ruptured and non-ruptured groups (24.4% vs 7.3%; P = 0.031).

Conclusion

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography (US) are of major value in the diagnosis of preoperative tumor rupture, and immediate surgery or delayed surgery are available therapeutic methods. The treatment plan was based on patients’ general conditions, tumor size, position and impairment degree of tumor rupture, extent of invasion and experience of a multidisciplinary team (including surgeon and anesthesiologists). In our experience, for ruptured preoperative tumor diagnosed with stage III, the criteria for immediate surgery are as follows: tumor not acrossing the midline, tumor without inferior vena cava thrombus, localized rupture, being capable of complete resection. Selection criteria for delayed surgery after preoperative chemotherapy are as follows: large tumors, long inferior vena cava tumor thrombus, tumors infiltrating to surrounding organs, unlocalized rupture, tumors can not being resected completely. Additionally, patients with preoperative Wilms tumor rupture had an increased risk of postoperative recurrence or metastasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wilms tumor is a common malignancy, accounting for 6% of all malignant pediatric tumors and 90% of all malignant renal tumors in children [1]. The prognosis has improved dramatically in recent years, and the 5-year overall survival for patients with Wilms tumor is more than 90% [2]. The timing of surgery for Wilms’ tumour has been a subject of lively debate for many years. The North American National Wilms’ Tumour Study Group (NWTSG) has always favoured immediate surgery, with subsequent chemo- and radiotherapy based on a carefully defined pathological staging system that assesses both the extent of tumor spread and the success of surgical resection at the time of operation. The International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) Nephroblastoma Trial Group, by contrast, has advocated and employed preoperative chemotherapy, usually 4–8 weeks of vincristine (VCR) and actinomycin D (ACTD). Postoperative treatment is determined by postoperative stage and histological subtype, and also the degree of histological response to the preoperative chemotherapy [3]. Though the NWTSG and SIOP philosophies differ, there is no obvious difference in the event-free (EFS) and overall survival (OS) between contemporaneous studies such as NWTS 4 and SIOP 9 [3]. Tumor spillage of Wilms tumor increases the risk of abdominal recurrence to 20% [4], which is considered to be present if there has been preoperative tumor rupture, intraoperative tumor spill, or a tumor biopsy. Although intraoperative tumor spill and tumor biopsy are intervention-related events, preoperative tumor rupture can be spontaneous or occur after trauma [4].

Tumor rupture, although rare, has serious implications. According to the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) criteria, every patient presenting with preoperative or intraoperative WT rupture must be classified as stage IIIc and receive abdominal radiotherapy, along with intensified chemotherapy [5]. The National Wilms Tumor Study (NWTS) also recommends that rupture of spillage, including biopsy of the tumor, is now included in stage III.

The Clinical signs of possible tumor rupture were acute abdominal pain, and/or fall of hemoglobin, and/or a recent history of abdominal trauma. Clinical symptoms were not typical in some patients with small break of tumor and minor hemorrhage. Therefore, radiologic definition of preoperative Wilms tumor ruptures is important for diagnoses and treatments. Preoperative Wilms tumor rupture is rare described in some case reports. The reported radiologic descriptions of preoperative Wilms tumor rupture are very limited. Once diagnosed with preoperative Wilms tumor rupture, immediate nephrectomy or delayed nephrectomy following preoperative chemotherapy are still under debate. In this study, we want to perform a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients treated for Wilms tumor and (1) to describe the clinical and radiologic features of preoperative Wilms tumor rupture; (2) to investigate indications for the two methods: immediate surgery and delayed surgery; (3) to analyze prognosis between ruptured and non-ruptured Wilms tumor.

Materials and methods

Clinical materials

From January 2008 to September 2017, 565 patients with pathology-confirmed Wilms tumor were registered in our hospital. The Clinical signs of possible tumor rupture were acute abdominal pain, and/or fall of hemoglobin. The radiologic signs of tumor rupture are as follows: (1) retroperitoneal and/or intraperitoneal effusion; (2) acute hemorrhage located in the sub-capsular and/or perirenal space; (3) tumor fracture communicating with peritoneal effusion; (4) bloody ascites. A retrospective analysis of preoperative Wilms tumor rupture was performed including age at diagnosis, gender, side of the tumor, clinical and radiologic signs, type of surgery, size of tumour, histology, type of postoperative treatment, presence of recurrence and metastasis, follow up time, and outcome. In our study, ruptured tumors were classified as at least stage III. Patients without preoperative Wilms tumor rupture at stage III during the same period were selected for our study.

Follow-up and statistical analysis

All patients were regularly monitored with surveillance for the recurrence and metastasis using ultrasonography and computed tomography. Event-free survival (EFS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of recurrence or metastasis). Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of last follow-up or disease-related death. EFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the independent-samples t test. Categorical variables were analyzed with χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0.

Results

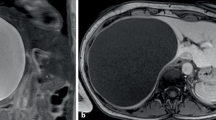

565 Patients with Wilms tumor were confirmed at pathology from January 2008 to September 2017. Of these patients, 45 patients were diagnosed with preoperative ruptured Wilms tumor according to clinical and radiologic signs. All preoperative rupture were confirmed at surgery. Spontaneous tumor rupture occurred in 41 patients, the other 4 patients had traumatic history. Of the 45 patients, 41 were classified as stage III, 3 patients with pulmonary metastases were classified as stage IV, and 1 patient with bilateral tumors were classified as stage V. 41 Patients at stage III were defined as ruptured group, and the ruptured group were categorized into immediate group (immediate surgery without preoperative chemotherapy) and delayed group (delayed surgery following preoperative chemotherapy). In ruptured group, there were 24 males and 17 females with a mean age of 42.4 months (ranging 5–93 months). The locations of the lesion were left side in 20 cases and right side in 21 cases. Of the 30 patients with clinical and radiologic signs of tumor rupture, 24 patients had acute abdominal pain, 16 had acute fall of hemoglobin, 4 had recent history of abdominal trauma. And intraperitoneal bloody ascites were seen in 18 patients which were considered to have intraperitoneal rupture, and 12 had retroperitoneal rupture with retroperitoneal effusion on imaging studies. The other 11 patients were clinically inapparent. And CT and US showed retroperitoneal encapsulated effusion suggesting old tumor rupture. In ruptured group, 13 patients had immediate surgery, 28 patients had delayed surgery after preoperative chemotherapy. In immediate group, 12 patients had localized rupture (Fig. 1a), 1 patient underwent emergency surgery because of continuous bleeding. In delayed group, 4 had inferior vena cava tumor embolus [one thrombus extended to inferior vena cava behind the liver, three thrombi got to the right atrium (Fig. 1b)], 4 crossed the midline with large tumors (Fig. 1c), 20 had extensive rupture without localization (Fig. 1d). In ruptured group, tumors ranged from 4.7 to 25.0 cm in maximum diameter with a mean of 12.0 cm and the volume ranged from 29.5 to 2056.6 cm3 (mean 533.6 cm3).

In immediate group, 13 cases had immediate nephrectomy. One patient underwent emergency surgery because of continuous bleeding. Before surgery, we tried to use renal arterial embolization to control hemorrhage, but failed. The other 12 patients with localized rupture and stable vital signs underwent immediate nephrectomy. Tumor rupture were confirmed at surgery and complete excision of tumors were achieved in 13 patients. The mean blood loss was 78 ml (range 5–300 ml), and the mean time on operation was 141 min (range 75–240 min). 13 tumors were classified as Favorable Histology based on the pathological results (5 were blastemal type and 8 were mixed type).

In delayed group, 28 patients had delayed nephrectomy after 1–20 weeks of chemotherapy with vincristine (VCR) and/or actinomycin D (ACTD). Of the 28 patients, 4 patients had inferior vena cava tumor embolus (1 thrombus shrank from inferior vena cava behind the liver to the renal vein level after preoperative chemotherapy, 1 got changed from the right atrium to the renal vein and the other 2 thrombi extending to the right atrium were unchanged after preoperative chemotherapy), 4 patients with large tumors crossing the midline, 20 patients had extensive rupture without localization. Tumors were totally removed in 28 cases. The mean blood loss was 118 ml (range 3–1200 ml), and the mean time of operation was 204 min (range 85–580 min). The pathological type showed: 5 were blastemal type, 10 were mixed type, 1 were epithelial type, 2 were stromal type, 3 were regressive type, 2 were completely necrotic, 1 were fetal rhabdomyoma nephroblastoma and 4 were non-typable showing changes of post-chemotherapy. Tumor rupture were confirmed at surgery and postoperative histopathology. All patients received postoperative chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy, according to SIOP/NWTS system (Table 1). Figure 2 indicates the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway of the patients with suspected tumor rupture.

The median follow-up time of ruptured group was 27.4 months (range 6–106 months). In the immediate group, tumor recurrence and metastasis developed in 2 patients, and no death occurred. In the delayed group, tumor recurrence and metastasis developed in 8 patients, and 7 patients died.

We collected clinical data of patients without preoperative Wilms tumor rupture at stage III during the same time. Finally, 41 patients were enrolled in non-ruptured group including 23 males and 18 females with a mean age of 39.9 months (ranging 1–96 months). Tumor was located at left in 22 cases and right in 19 cases. The maximum diameter ranged from 4.1 to 22.3 cm with a mean of 11.5 cm and the volume ranged from 21.6–2175.4 cm3 (mean 534.4 cm3). The pathological type showed: 8 were blastemal type, 16 were mixed type, 1 were epithelial type, 7 were stromal type, 9 were non-typable showing changes of post-chemotherapy. Postoperative treatments are based on SIOP/NWTS system. At a median follow-up of 48.4 months (range 2–120 months), tumor recurrence and metastasis developed in 3 patients, and 4 patients died. The clinical materials of 41 patients in non-ruptured group were shown in Table 2 with the ruptured group.

The median survival time of ruptured group (IS + DS group) was (85.1 ± 7.5) months, and the 3-year cumulative survival rates was 75.1%. The median survival time of non-ruptured group was (110.3 ± 5.6) months, and the 3-year cumulative survival rates was 89.6%. The overall survival rate between ruptured and non-ruptured groups showed no statistic difference (P = 0.256, Fig. 3). However, there was significant difference in recurrence or metastases rate between ruptured and non-ruptured groups (24.4% vs 7.3%; P = 0.031, Fig. 4).

Discussion

Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma) is the most common malignant renal tumor in children. 75% of patients occur mostly under 5 years and the peak incidence is between 2 and 3 years [6]. Preoperative Wilms tumor rupture is rare and most of the literatures on this disease are case reports. Leape et al. [7] reported that 3.1% of patients (19 of 606 patients) experienced preoperative tumor rupture. And it was 23% (57/250) in Brisse’s study [8]. In our study, 45 of these 565 patients diagnosed with preoperative Wilms tumor rupture (8.0%). Preoperative tumor rupture can be spontaneous or occur after trauma [9]. In our study, 4 of the 45 patients had traumatic history. Spontaneous tumor rupture was strongly associated with overgrowth of the tumor and necrosis. According to reports in the literature, the risk of tumor rupture could significantly increase if the diameter is larger than 5 cm [10, 11]. The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) reported that a larger tumor size is a risk factor for intraoperative tumor spillage. This report stated that the odds of intraoperative tumor spillage were 2.183 times greater for patients with a maximum tumor diameter ≥ 12 cm compared with < 12 cm [12]. No similar studies about preoperative tumor rupture were found in the literature. In our study, the mean maximum dimension of ruptured group was 12.0 cm, and the maximum diameter can be up to 25.0 cm.

In our study, we defined “preoperative tumor rupture” mainly depending on imaging examinations together with clinical symptoms. The Clinical signs of possible tumor rupture were acute abdominal pain, and/or fall of hemoglobin, and/or a recent history of abdominal trauma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography (US) were performed for the suspected Wilms tumor rupture. The radiologic criteria of tumor rupture were as follows: (1) retroperitoneal and/or intraperitoneal effusion; (2) acute hemorrhage located in the sub-capsular and/or perirenal space; (3) tumor fracture communicating with peritoneal effusion; (4) bloody ascites. For the diagnostic performance of CT in identifying the presence or absence of preoperative Wilms tumor rupture, Geetika Khanna et al. conducted a double-blind study trial and a matched-pair analysis showing that CT has moderate specificity but relatively low sensitivity in the detection of preoperative Wilms tumor rupture. Ascites beyond the cul de sac, irrespective of attenuation, is most predictive of rupture [4]. In our study, Clinical signs of possible preoperative rupture were observed in 30 of 41 patients. Radiologic signs of tumor rupture were observed in all 41 patients. Among patients with radiologic signs of tumor rupture, 11 of 41 patients had no symptoms.

For patients with preoperative Wilms tumor rupture, initial treatment involved stabilization of hemodynamic status by fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion. The surgical management of preoperative Wilms tumor rupture need future investigation, regardless of immediate surgery or delayed surgery. Emergency surgery is indicated for patients with continuous bleeding and hemorrhagic shock. The emergency surgery rate for Wilms tumor rupture previously was estimated at between 1.8 and 3% [8]. In our study, 1 of 41 patients (2.4%) took emergency surgery because of uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock. In stable patients, immediate surgery or delayed surgery are available therapeutic methods. The treatment plan was based on patients’ general conditions, tumor size, position and impairment degree of tumor rupture, extent of invasion and experience of a multidisciplinary team (including surgeon and anesthesiologists). Based on our experience, the selection criteria for immediate surgery are as follows: tumor not acrossing the midline, tumor with out inferior vena cava thrombus, localized rupture, being capable of complete resection. Selection criteria for delayed surgery after preoperative chemotherapy are as follows: large tumors, long inferior vena cava tumorm thrombus, tumors infiltrating to surrounding organs, unlocalized rupture, tumors can not being resected completely. In our study, 12 cases took immediate nephrectomy without preoperative chemotherapy, 28 cases took delayed nephrectomy after preoperative chemo-therapy (including 4 cases with inferior vena cava tumor embolus, 4 cases with large tumors crossing the midline, 20 cases having extensive rupture without localization). Postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy are based on SIOP/NWTS system (Table 1). Figure 2 indicates the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway of the patients with suspected tumor rupture.

The survival rate of patients who have Wilms tumor is relatively high [13, 14] compared with patients who have other pediatric cancers, even after disease recurrence [15]. In our study, the median survival time with ruptured Wilms tumor was (85.1 ± 7.5) months, and the 3-year cumulative survival rates was 75.1%. The median survival time with non-ruptured Wilms tumor was (110.3 ± 5.6) months, and the 3-year cumulative survival rates was 89.6%. Overall survival rate between ruptured and non-ruptured group showed no statistic difference (P = 0.256). Preoperative tumor rupture is a major risk factor for abdominal recurrence, although it is rare [16]. In this study, there was significant difference in recurrence or metastases rate between the ruptured and non-ruptured groups (24.4% vs 7.3%; P = 0.031).

Conclusions

Preoperative tumor rupture is a rare disease with acute onset and rapid progression. Immediate surgery or delayed surgery are available therapeutic methods. Immediate surgery can be performed if patients have tumors: not acrossing the midline, with out inferior vena cava thrombus, localized rupture, being capable of complete resection. Conversely, preoperative chemotherapy prior to tumor resection is necessary to shrink the large tumors and localize the tumor rupture range. Additionally, patients with preoperative Wilms tumor rupture had an increased risk of postoperative recurrence or metastasis.

Because preoperative tumor rupture can cause life-threatening symptoms, increase the risk factor for abdominal recurrence and lead to a relatively poor prognosis, timely recognition, rapid and reliable diagnosis, effective management are significantly important. Due to the small number of patients, there may be bias in statistics. Therefore, the above conclusions needs to be further confirmed through long term follow-up studies and large-scale samples.

References

Brok J, Treger TD, Gooskens SL et al (2016) Biology and treatment of renal tumours in childhood. Eur J Cancer 68:179–195

Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF et al (2010) Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol 28:2625–2634

Mitchell C, Pritchard-Jones K, Shannon R et al (2006) Immediate nephrectomy versus preoperative chemotherapy in the management of non-metastatic Wilms’ tumour: results of a randomised trial (UKW3) by the UK Children’s Cancer Study Group. Eur J Cancer 42(15):2554–2562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2006.05.026

Khanna G, Naranjo A, Hoffer F et al (2013) Detection of preoperative Wilms tumor rupture with CT: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Radiology 266(2):610–617

Le Rouzic MA, Mansuy L, Galloy MA, Champigneulle J, Bernier V, Chastagner P (2019) Agreement between clinicoradiological signs at diagnosis and radiohistological analysis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy of suspected Wilms tumor rupture: consequences on therapeutic choices. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66(6):e27674. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27674

Nakamura L, Ritchey M (2010) Current management of Wilms’ tumor. Curr Urol Rep 11(1):58–65

Leape LL, Breslow NE, Bishop HC et al (1978) The surgical treatment of Wilms’ tumor: results of the National Wilms’ Tumor Study. Ann Surg 187(4):351–356

Brisse HJ, Schleiermacher G, Sarnacki S et al (2008) Preoperative Wilms tumor rupture: a retrospective study of 57 patients. Cancer 113(1):202–213

Ehrlich PF, Ritchey ML, Hamilton TE, et al (2005) Quality assessment for Wilms’ tumor: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study-5. J Pediatr Surg 40(1):208–212; discussion 212–213

Pritchard-Zhu LX, Geng XP, Fan ST (2001) Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma and vascular injury. Arch Surg 136:682–687

Shiota M, Kotani Y, Umemoto M et al (2012) Study of the correlation between tumor size and cyst rupture in laparotomy and laparoscopy for benign ovarian tumor. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 38:531–534

Gow KW, Barnhart DC, Hamilton TE, Kandel JJ, Chen MK, Ferrer FA et al (2013) (2013) Primary nephrectomy and intraoperative tumor spill: report from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Renal Tumors Committee. J Pediatr Surg 48:34–38

Green DM, Breslow NE, Beckwith JB et al (1998) Effect of duration of treatment on treatment outcome and cost of treatment for Wilms’ tumor: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol 16:3744–3751

Tournade MF, Com-Nougue C, de Kraker J et al (2001) Optimal duration of preoperative therapy in unilateral and nonmetastatic Wilms’ tumor in children older than 6 months: results of the Ninth International Society of Pediatric Oncology Wilms’ Tumor Trial and Study. J Clin Oncol 19:488–500

Green DM, Cotton CA, Malogolowkin M et al (2007) Treatment of Wilms tumor relapsing after initial treatment with vincristine and actinomycin D: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48:493–499

Shamberger RC, Guthrie KA, Ritchey ML et al (1999) Surgery related factors and local recurrence of Wilms tumor in National Wilms Tumor Study 4. Ann Surg 229:292–297

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Song, Hc., Yang, Yf. et al. Preoperative Wilms tumor rupture in children. Int Urol Nephrol 53, 619–625 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-020-02706-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-020-02706-5