Abstract

The aim of this research was to examine conditions that modify feminists’ support for women as targets of gender discrimination. In an experimental study we tested a hypothesis that threatened feminist identity will lead to greater differentiation between feminists and conservative women as victims of discrimination and, in turn, a decrease in support for non-feminist victims. The study was conducted among 96 young Polish female professionals and graduate students from Gender Studies programs in Warsaw who self-identified as feminists (M age = 22.23). Participants were presented with a case of workplace gender discrimination. Threat to feminist identity and worldview of the discrimination victim (feminist vs. conservative) were varied between research conditions. Results indicate that identity threat caused feminists to show conditional reactions to discrimination. Under identity threat, feminists perceived the situation as less discriminatory when the target held conservative views on gender relations than when the target was presented as feminist. This effect was not observed under conditions of no threat. Moreover, feminists showed an increase in compassion for the victim when she was portrayed as a feminist compared to when she was portrayed as conservative. Implications for the feminist movement are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2010 we celebrated the “Year of the Woman” in U.S. politics (Parker 2010, para. 1). Many women, like Tea Party leaders such as Sarah Palin and Christine O’Donnell, were ranked among the most successful politicians of 2010 and appeared to be on their way to becoming “the 21st century symbol of American women in politics” (Holmes and Traister 2010, para. 3). At the same time, women all over the world continue to be under-represented in the majority of political and business institutions. For example, only 14 countries have democratically elected female leaders (Catalyst 2012a) and a gender gap still exists even in most egalitarian societies (Hausmann et al. 2012). Also, despite the socialist rhetoric of gender equality, gender discrimination remains an ongoing problem in the post-Communist region, including Poland (see Catalyst 2012b; Graff 2003, 2007; Olson et al. 2007). For example, in the EU, compared to other member states, the gender gap tends to be higher in post-Communist countries (Hausmann et al. 2012). These seemingly conflicting realities, in addition to the conservative, non- or even anti-feminist identities of many successful female politicians, have left the feminist community somewhat puzzled. “Do you still cheer if the ceiling is crashed by (…) conservative businesswomen?” wondered Sarah Libby (2010, para. 3) in Slate, and several feminist journalists and bloggers shared her concern during the so-called “Year of the Woman” (e.g. Daum 2010; Douthat 2010; Harding 2010; Wall 2010). Such reservations may indicate little more than a cautious attitude adopted by advocates for women’s rights. Ongoing institutional and cultural sexism worldwide certainly casts doubt on the “mission accomplished” undertones of slogans such as “Year of the Woman.” Another, if somewhat more cynical question may be asked by some: when does feminist support become reserved only for fellow feminists? We sought to address this question with a study conducted among Polish feminists.

The aim of this paper is to investigate the conditions under which women that identify themselves as feminists might show a decrease in support for other women. Support for female political candidates expresses not only support for other women but also for the gender-related policies they might (or might not) endorse. Thus, in this study we investigated factors that can modify feminists’ reactions to gender-based discrimination in the workplace as a more neutral context. Drawing on theories of social identity (Tajfel and Turner 1986) and social self-categorization (Turner et al. 1987; 1984), the major question we address here is how threat to perceiver’s feminist social identity might affect their response to the victim of gender discrimination. We further investigate attitudes toward a victim of gender discrimination depending on whether the victim is portrayed as sharing or not sharing feminist identity with the perceiver. Specifically, in an experimental study we examine the influence of the victim’s worldview and threats to feminist identity on reactions to gender discrimination. We investigated two components of response to gender discrimination: compassion for the victim (Leung et al. 1993)—an emotional component likely to increase victim helping (for evidence from the U.S. see e.g. Batson 1991; Cialdini et al. 1987 and Poland e.g. Karyłowski 1982) and perceptions of the situation as unfair which corresponds to the cognitive interpretation of discrimination (Major et al. 2002; Roy et al. 2009).

Previous research conducted in the U.S. has focused on factors that modify the perception of discrimination, including whether the victim was an in-group member (Dodd et al. 2001; Garcia et al. 2005, 2010; Schmitt et al. 2003) or whether she was feminist (Roy et al. 2009). However, none of these studies examined ways feminists react to discrimination. Feminists, across different cultures, are the ones who are most likely to be sensitive to gender discrimination and act against it (as shown in the U.S.: Cowan et al. 1992; Duncan 1999; Myaskovsky and Wittig 1997; Nelson et al. 2008; Williams and Wittig 1997; Zucker 2004; see also Graff 2003, on Poland). Because they are advocates for gender equality and the actors of social change, it is important to know what factors might influence their perception of gender issues. It is especially important to know what modifies perceptions of discrimination among feminists in contexts where research on feminist movement is still scarce. Hence, we test our research questions in Poland, among female graduate students and young professionals who self-identify as feminists. We will discuss the specific cultural context in which the study was conducted and demonstrate its relevance to the understanding of feminist attitudes and discrimination in other cultures. We then outline our empirical predictions by discussing the role of the target’s social identity and threat in responses to discrimination.

Gender Equality and Feminism in Poland

Despite “illusions of egalitarianism” (Malinowska 1995, p. 35) crafted by the Communist system, gender equality has not been achieved in post-Communist Poland (Graff 2007; Hausmann et al. 2012; Marsh 2009; see also Malinowska 1995; Olson et al. 2007). While Communism increased representation of women in the job market, it sustained gender inequality by employing them mostly in low-status jobs and increasing the burdens placed on them (Marsh 2009; Mathews et al. 2005; Olson et al. 2007). Enduring these burdens and sacrificing oneself for the family has been seen as a unique virtue expected from Polish women (Graff 2007).

Nevertheless, just after the system changed there were strong doubts about the existence of a movement that would take upon itself the struggle for greater gender equality (Bystydzienski 2001; Graff 2003). Feminist ideas were being rejected because of their association with Communism and opposition from a revived Catholic church (Bystydzienski 2001; Graff 2003, 2007; Marsh 2009). Fortunately, the situation has been slowly changing. As Graff (2003) put it: “whatever one’s definition of feminism (…), there is no doubt that it does exist in today’s Poland” (p. 101). Several large feminist organizations exist in Poland, including eFKa (www.efka.org.pl) & Feminoteka (www.feminoteka.pl), both aiming to support female solidarity and to counteract gender discrimination, Polish Federation for Women and Family Planning, focusing on reproductive rights (http://www.federa.org.pl), and Women’s March 8th Agreement, organizing annual feminist manifestation Manifa (www.manifa.org), among others.

Despite its unique history, Polish feminism bears some similarities to the movements in countries with a longer feminist tradition (Graff 2003, 2007). First, it uses third wave tactics (such as irony and pop cultural references; Graff 2003) although it is focused on issues and goals associated with second wave feminism. A major concern of Polish feminists has traditionally centered on abortion rights, but domestic violence, employment equality, and issues of political representation have made their way to the agenda (Graff 2003). Second, despite being a relatively young movement in the Polish society, it is experiencing anti-feminist backlash (Bystydzienski 2001; Graff 2003, 2007). Because of these similarities, our examination of the effects of social identity and threat on feminists’ attitudes towards victims of gender discrimination can be informative not only for the movement in Poland but also for feminists in other countries. Moreover, it has the potential to provide information about feminism in the understudied post-Communist region (notable exceptions of studies from Sex Roles include Henderson-King and Zhermer 2003, on Russia, and Mathews et al. 2005, on Hungary).

Feminist Identity and Gender Discrimination

The embattled state of both the historical and contemporary term across the world notwithstanding, feminist attitudes are generally defined as beliefs in the goal of gender equality in the social system (Williams and Wittig 1997; Zucker 2004). Feminist identity, on the other hand, is typically defined as a collective or social identity (Burn et al. 2000; Henderson-King and Stewart 1994, 1997) and self-identification as a member of a group of feminists (Ashmore et al. 2004; Eisele and Stake 2008). Feminist identification among women reflects identity of a woman and a feminist. Indeed, feminist self-identification is not only a predictor of feminist attitudes but has also been shown to be a predictor of collective action on behalf of women in the U.S. (Breinlinger and Kelly 1994; Cowan et al. 1992; Nelson et al. 2008; Williams and Wittig 1997). For example, Zucker (2004) found that U.S. women who self-identify as feminists show higher scores of feminist consciousness and feminist activism than do liberal egalitarians, defined as those who support the equality of women and men but simultaneously reject feminist identity.

Based on this evidence, feminist identity can be viewed as a politicized collective identity—a form of collective identity that underlies group members’ motivation to engage in power struggle between groups (shown for instance in the U.S. and Germany; Simon et al. 1998; Simon and Klandermans 2001), or opinion-based identity—a predictor of political behavioral intentions (as demonstrated in Romania and Australia by Bliuc et al. 2007). Feminist identity, then, constitutes a special case of female identity organized around endorsement of equal rights for women (e.g. Duncan 1999). Thus, in principle feminists should support striving for equality on behalf of all women regardless of these women’s views, convictions or background (Gillis et al. 2004).

At the same time, feminist identity has classically been defined in opposition to some specific worldviews, such as conservative ideology (see Liss et al. 2001 in the U.S. and Frąckowiak-Sochańska 2011 in Poland). Because of their self-definition against traditionalism and political conservatism, feminists might be likely to engage in differentiation (Jetten et al. 2004) between women who hold traditional or conservative views versus feminist or liberal views. Thus, feminists may see conservative women as out-group members. Taking this observation a step further, feminists’ reactions to gender-based discrimination might depend on sharing social identity with discrimination victims (Tajfel and Turner 1986; Turner et al. 1987).

Previous studies demonstrate that members of in-groups and out-groups who experience discrimination are responded to differently. Several studies conducted in the U.S. (Dodd et al. 2001; Garcia et al. 2010; Schmitt et al. 2003) demonstrate that individuals who challenge discrimination trigger positive responses from in-group members. This is most likely when the situation is unambiguous (Dodd et al. 2001; Schmitt et al. 2003), but the response might become negative in instances that are not clearly discriminatory or when victims’ behavior violates in-group norms (as shown in the U.S. by Garcia et al. 2005; Kaiser et al. 2006; Kaiser and Miller 2001). If reactions to gender-based discrimination are affected by the social identity of the victim, it is also possible that feminists’ response to discrimination will depend on whether the victim is an out-group member (a conservative woman) or an in-group member (a fellow feminist). We hypothesize that feminists will show more support to discrimination victim when they believe she holds feminist views but their response will be less positive when the victim is believed to hold conservative views on gender relations.

Threats to Feminist Identity

Similar to other movements that represent disadvantaged groups, feminism is a frequent target of backlash criticism in the U.S. (Burn et al. 2000; Haddock and Zanna 1994; Twenge and Zucker 1999). Typical accusations revolve around feminists being “anti-family” or “man-hating” and “frustrated radicals” (Kamen 1991). Anti-feminist backlash seems to be present even in countries without a long tradition of gender equality efforts, such as post-Communist Poland (Frąckowiak-Sochańska 2011; Graff 2003, 2007; Marsh 2009) and the Czech Republic (Heitlinger 1996). This is reflected in negative stereotypes about feminists that are similar in content to those prevalent in the U.S. (Frąckowiak-Sochańska 2011; Heitlinger 1996). The contentious position of the term is one reason that some women, despite favoring feminist goals, might be hesitant to call themselves feminists (a phenomenon noted e.g. in the U.S.: Ramsey et al. 2007; Williams and Wittig 1997; Zucker 2004, and Poland, Frąckowiak-Sochańska 2011). Backlash criticism reflects a threat to the value of feminist group membership (see Branscombe et al. 1999a and Riek et al. 2006 for a discussion on how it differs from other types of identity threats such as categorization, distinctiveness, or acceptance threats). In this paper we examine the consequences of such value threat to feminist identity for reactions of feminists to gender discrimination against women who do or do not share feminist views.

Prior research conducted in the U.S. and Canada suggests that threat in general leads to stronger conviction in and defense of one’s beliefs (McGregor et al. 2007; McGregor and Jordan 2007). Moreover, value threats to group identity may cause group members (especially the high identifiers) to stress group homogeneity, cohesiveness, and loyalty (as shown in the Netherlands, Doosje et al. 1995; Ellemers et al. 1997 and the U.S., Branscombe et al. 1999b; see also Branscombe et al. 1999a; Turner et al. 1984). It is possible that threat to feminist identity has the potential to strengthen the organizing value of the group: gender equality. In cases of gender discrimination, therefore, the experience of a threat to feminist identity may cause feminists to become even more sensitive to situations of gender discrimination and more supportive to its victims.

However, an alternative perspective is that threat to group value may lead to an increase in intergroup differentiation and in-group enhancement (demonstrated in the U.S., Branscombe and Wann 1994, and the Netherlands, Jetten et al. 2001; Spears et al. 1999; see also Ellemers et al. 2002; Tajfel and Turner 1986). Hence, threats to feminist identity may increase the salience of feminist identity over the female identity and, thus, strengthen the distinction between feminist in-group and conservative out-group. Therefore, when feminist identity is threatened, feminists might be motivated to emphasize the differences between those who do and do not share their worldview. If this is the case, especially under conditions of threat, reactions to gender-based discrimination may depend on the perceived social identity of the victim. If the victim shares a feminist worldview (i.e. is a member of the feminist in-group), identity threat may lead to an interpretation of the discriminatory situation as more unfair and to greater expressed compassion for the victim. However, if the victim holds conservative beliefs on gender roles and relations, identity threat may lead feminists to interpret the gender discrimination situation as less unfair and, thus, express less compassion for the victim.

Overview of the Study

The aim of the present study is to investigate the conditions that could moderate reactions of Polish self-identified feminists to gender discrimination. Our first set of hypotheses predicts a main effect for threat to feminist identity. We predicted that, compared to a no threat condition, under threat feminists will be more sensitive to discrimination, manifested by perceiving the situation as more unfair (Hypothesis 1a) and showing more compassion to the discrimination victim (Hypothesis 1b). We also predicted a main effect for feminist identity of the victim. We suggest that compared to a feminist victim (an in-group member), when the target is presented as conservative (an out-group member) feminists will perceive the situation as less unfair (Hypothesis 2a) and show less compassion to the discrimination victim (Hypothesis 2b).

Our third set of hypotheses predicts an interaction between target views and threat. We suggest that when threatened, feminist identity will lead to greater differentiation between feminist and conservative victims of discrimination, and therefore less compassion and fewer attributions of discrimination when the victim is non-feminist. More precisely, we hypothesized that when situationally threatened, feminists would perceive discriminatory treatment of a woman to be less fair (Hypothesis 3a) and show more compassion (Hypothesis 3b) when the victim is presented as a fellow feminist as compared to when the victim is presented as a non-feminist. We also predicted that, compared to a low-threat condition, when the feminist identity is threatened, unfairness experienced by a non-feminist victim of discrimination will be perceived as less severe (Hypothesis 3c) and deserving less compassion (Hypothesis 3d).

Furthermore, we examined whether the two responses to discrimination will be related by testing the hypothesis that perceptions of unfairness would mediate the relationship between victim’s views and compassion in response to discrimination. We expected that under threat the decreased compassion towards the conservative victim will be driven by attributions of responsibility to the victim rather than to unfair decision-makers (Heider 1958). In other words, we predicted an indirect effect of the feminist views manipulation on compassion via perceived unfairness only in the threat condition (Hypothesis 4).

To test these hypotheses, we conducted an experiment that manipulated threat to feminist identity and examined its effects on reactions to gender discrimination against a feminist or a conservative woman. Because feminists might differ in their strength of support for feminist ideology, which in turn might affect their reactions to discrimination (e.g. Morgan 1996, in the U.S. and Becker and Wagner 2009, in Germany), in testing our predictions we controlled for strength of feminist ideology in our study.

Method

Participants

The study was conducted in 2009. Participants were predominantly recruited among students of postgraduate Gender Studies of Institute of Social Sciences, University of Warsaw, which cover sociology, psychology, law, history, theories of culture, and literature from the gender identity perspective. Some questionnaires were also distributed among undergraduate students attending classes on Psychology of Gender and Women Studies at the University of Warsaw. Finally, some participants were recruited during the 1st Congress of Women held in Warsaw and among young professionals with a snowball technique. At the beginning of the study participants were asked whether they identify with feminists as a group. Only participants who self-identified as feminists were included in the sample. The initial sample included participants with age ranging from 19 to 40. The fact that our older participants were likely brought up under Communism could have affected their views on gender relations. Therefore, to maintain homogeneity of the sample, we included in the analyses only participants below the age of 30. The final sample consisted of 96 females. All of them were White and of Polish nationality. Their age ranged from 19 to 29 (M = 22.23, SD = 2.51).

Procedure

First, participants stated their identification with feminists as a group and filled in a measure of support for feminist ideology (Hankiewicz 2006). Next, they were then randomly assigned to one of the experimental conditions. The study had a 2 (identity threat vs. control) x 2 (feminist vs. conservative views of discrimination victim) design.

We manipulated threat to feminist identity by having participants read excerpts from an Internet forum discussion (see Appendix A for instructions and manipulation text). In the group identity threat (experimental) condition participants were presented with an excerpt that was critical/threatening of the feminist movement. In the control condition the excerpt included neutral opinions. The forum was presented as focusing on female issues. Effectiveness of the manipulation was checked with one item measuring perceived valence of the opinions: “Based on these excerpts, how do you assess the attitude of these women towards feminism?” (in Polish “Jak z powyższych wypowiedzi oceniasz stosunek tych kobiet do feministek?”). Participants could mark their answers on a scale from 1 (definitely negative) to 7 (definitely positive).

Later, we directed participants to read about an unfair promotion decision in which a marketing company chose not to grant a highly qualified woman (Anna B.) a managerial position in the firm and instead promoted a less qualified man. Participants were handed CVs and cover letters of the two candidates. The materials were prepared in such way that the female candidate’s qualifications seemed higher than the male candidate’s. After reading through the materials, participants received information that the company had decided to promote the male candidate. Also, to strengthen the perception of discrimination, participants learned that this decision was surprising to the candidate’s co-workers who thought that the female candidate was more qualified for this position than the male candidate. In this way, we sought to create the impression that the female candidate was a victim of gender discrimination.

The second experimental manipulation was embedded in the promotion materials of the female employee/discrimination victim (the male candidate materials were the same across all research conditions). By varying the content of the CV and cover letter we manipulated her views to be either conservative or feminist (see Appendix B for manipulation text and instructions). In the feminist views condition the female candidate’s CV included information about having an additional degree in Gender Studies and her cover letter mentioned collaboration with a feminist organization. In the conservative views condition an additional degree in Eastern Studies and collaboration with an organization that supports traditional values were mentioned instead. A one-item manipulation check was used: “The views of Anna B. [the character] are close to mine” (in Polish “Poglądy Anny B. są mi bliskie”). Participants were asked to what extent this sentence was true on a scale from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). Afterwards, participants were asked to respond to measures of perceptions of the situation as unfair and compassion for the victim. Then participants were thanked and carefully debriefed. The whole procedure took around 25 min.

Measures

Perception of the situation as unfair was measured with eight items adopted from Basińska (2006, see Appendix C). Participants were asked to rate on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree) to what extent they agreed with these statements. Scores on all items were averaged to create a measure of perception of the situation as unfair (α = .79).

Compassion was measured as a DV with two items capturing sympathy for the victim (Basińska 2006, see Appendix C). Participants were asked to rate on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree) to what extent they agreed with these statements. The two items were positively correlated, r (94) = .49, p < .001, so their scores were averaged to create a measure of compassion.

Support for Feminist Ideology

We also controlled for the strength of support for feminist ideology. This variable was measured with 11 items (see Appendix C) from the Polish adaptation (Hankiewicz 2006) of the Liberal Feminist Attitude and Ideology Scale developed by Morgan (1996). Participants were asked to what extent they agree with these statements. Their answers could range from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). All items were averaged to create a measure of support for feminist ideology (α = .87).

Results

Descriptive and Correlational Analyses

Means and standard deviations for all continuous variables are presented in Table 1. On average participants showed fairly high endorsement of feminist ideology confirming that the sample consisted of feminists. Participants also perceived the situation as generally unfair, and showed rather strong compassion for the victim. Correlations between our dependent and control variables were also computed. Perceived unfairness and compassion for the victim were significantly positively correlated, r (94) = .57, p < .001. Both perceived unfairness, r (94) = .27, p = .01, and compassion for the victim, r (94) = .30, p = .003, were significantly positively correlated with strength of support for feminist ideology.

Manipulation Checks

In the first step of data analysis we checked the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation. A 2 × 2 ANOVA was conducted to check whether the perceived valence of presented opinions differed according to the two experimental manipulations. Results revealed a significant main effect of threat manipulation indicating that participants in the control condition perceived the opinion as more positive (M = 4.20, SD = 0.69) than participants in the threat condition (M = 1.32, SD = 0.47), F (1,92) = 573.47, p < .001, partial ŋ2 = .86. Neither the main effect of victim’s views, nor the interaction effect of the two experimental manipulations, were significant.

Similarly, a 2 × 2 ANOVA was conducted to check whether the perception of target’s views differed according to the two experimental manipulations. Results revealed a significant main effect of the victim target’s views manipulation indicating that participants in the feminist views condition (M = 3.57, SD = 1.14) perceived victim’s views as more similar to their own views than participants in the conservative views condition (M = 2.04, SD = 1.27), F (1,92) = 37.62, p < .001, partial ŋ2 = .29. Neither the main effect of threat manipulation, nor the interaction effect of the two experimental manipulations, were significant.

Experimental Effects

To examine the effects of experimental manipulation a 2 × 2 between-subjects multivariate analysis of covariance was performed, followed up by univariate analyses of covariance on the two dependent variables: perceived unfairness of discrimination and compassion toward the victim (Table 2). Because strength of support for feminist ideology correlated significantly with our two dependent variables, we included it in all analyses as a covariate (the pattern of results remains similar when this variable is not controlled for).

The first set of hypotheses predicted that, compared to a control condition, when feminist identity was threatened the situation will be perceived as more unfair (Hypothesis 1a) and the target will receive more compassion (Hypothesis 1b). MANCOVA revealed that the main effect of threat was not significant, Wilk's λ = .96, F (2, 90) = 1.95, p = .15, partial ŋ2 = .04. Follow-up ANCOVAs confirmed that manipulation of threat did not significantly affect perceived unfairness or compassion. Thus, the analyses did not support Hypotheses 1a and 1b.

The second set of hypotheses predicted that, compared to a feminist target, when the target is presented as conservative the situation will be perceived as less unfair (Hypothesis 2a) and the victim will receive less compassion (Hypothesis 2b). MANCOVA revealed that there was a marginally significant main effect of victim’s views, Wilk’s λ = .94, F (2, 90) = 2.86, p = .06, partial ŋ2 = .06. Follow-up ANCOVAs indicated that the manipulation of victim’s views did not affect perceived unfairness, failing to support Hypothesis 2a. However, in support for Hypothesis 2b, the victim’s views manipulation significantly affected compassion for the victim (Table 2). Participants were less compassionate toward a conservative (M = 4.01, SD = 0.71) than toward a feminist victim (M = 4.31, SD = 0.73).

The third set of hypotheses predicted an interaction between target’s views and threat on perceived unfairness and compassion for the victim. MANCOVA did not reveal a significant interaction of manipulation of threat and victim’s views, Wilk’s λ = .95, F (2, 90) = 2.32, p = .10, partial ŋ2 = .05. However, follow-up ANCOVAs indicated that the interaction effect was significant for perceptions of unfairness, F (1, 91) = 4.35, p = .04, partial ŋ2 = .05 (see Tables 2 and 3). To test Hypotheses 3a and 3b we used simple main effects analysis with Bonferroni’s adjustment for multiple comparisons. These analyses supported Hypothesis 3a that when participants’ feminist identity was threatened, the situation of discrimination was perceived as more unfair when the target had feminist views (M = 4.08, SD = 0.72) than when she had conservative views (M = 3.75, SD = 0.57), p = .02. There were no differences between conservative (M = 4.15, SD = 0.50) and feminist (M = 4.07, SD = 0.47) target’s views in the no threat condition, p = .60. Furthermore, the analyses revealed that when the target was presented as a fellow feminist, perceived unfairness did not change in the threat condition compared to the no threat condition, p = .82. However, when the target was presented as having a more conservative worldview, participants perceived the situation of discrimination as less unfair in the identity threat condition than in the no threat condition, p = .01, supporting Hypothesis 3c.

ANCOVA indicated that the interaction effect did not reach statistical significance for compassion toward the victim, F (1, 91) = 0.31, p = .58, partial ŋ2 = .003 (see Table 2). However, follow-up comparisons with Bonferroni’s adjustment revealed only a significant effect of victim’s views on compassion in the threat condition (Table 4). In line with Hypothesis 3b, when feminist identity was threatened, participants reported more compassion when the target had feminist views (M = 4.22, SD = 0.76) than when she had conservative views (M = 3.88, SD = 0.81), p = .04. Hypothesis 3d, predicting that a conservative victim would receive less compassion in the identity threat condition than in the no threat condition, was not supported, p = .12.

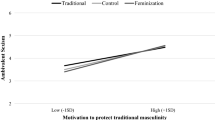

In the final step of data analysis, we tested Hypothesis 4 predicting that there would be an indirect effect of the feminist views manipulation on compassion via perceived unfairness in the threat condition but not in the control condition. To this end we probed the significance of conditional indirect effects of the victim’s views on compassion toward the victim via perceived unfairness (mediator) depending on the threat manipulation (moderator). Feminist ideology was included in this analysis as a covariate (the pattern of results remains the same when this variable is not controlled for). We followed the bootstrapping procedure proposed by Preacher et al. (2007; Hayes 2009) to test for moderated mediation (Muller et al. 2005). We used the MODMED macro (Model 2, Preacher et al. 2007). For each level of the moderator we requested 10,000 bootstrap samples. The indirect effect of target’s views presentation on compassion via perceived unfairness was positive and significant only in the threat condition: the indirect effect had a bootstrap 95% bias corrected confidence interval of .04 to .58 (Fig. 1). The indirect effect in the no threat condition was not significant with a bootstrap 95% bias corrected confidence interval of −.26 to .10 (Fig. 2). Therefore, we received support for Hypothesis 4.

Mediated effect of victim’s views on compassion through perceptions of the hiring decision as unfair in the threat condition. Note. Entries are unstandardized regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses, dotted line indicates total effect (not controlling for the third variable) * p < .05. *** p < .001

Mediated effect of victim’s views on compassion through perceptions of the hiring decision as unfair in the no threat condition. Note. Entries are unstandardized regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses, dotted line indicates total effect (not controlling for the third variable) *** p < .001

Discussion

In this paper we examined factors that influence feminists’ reactions to gender discrimination. Participants, all self-identified feminists, were presented with a description of gender discrimination in the workplace. Results confirmed our prediction that feminists’ responses to the situation depended on who the victim of discrimination was and whether feminist identity was threatened. The situation was more likely to evoke greater compassion towards the victim when the victim was presented as a feminist (an in-group member) than when she was presented as conservative (an out-group member). Hypotheses predicting main effects of threat were not supported. However, we found a significant interaction of threat to feminist identity with victim’s worldview on perceived unfairness. Analyses revealed that under identity value threat the situation was perceived as more unfair when the victim was a fellow feminist than when she was presented as conservative. Also, only when the victim was presented as having conservative views, compared to a low-threat condition, feminist identity threat decreased perception of the situation as unfair.

We did not find an interaction between threat and victim’s views on compassion towards the victim. It is possible that the experimental manipulations affected cognitive and emotional responses differently. The main effect of increased compassion towards the feminist victim relative to a conservative one might have overridden the interaction effect. Nevertheless, follow- up comparisons indicated that, in line with our predictions, in the threat condition participants expressed less compassion for the conservative victim than the feminist one. Because the interaction effect for compassion did not reach statistical significance, this result should be interpreted with caution. More importantly, moderated mediation analyses demonstrated that only in the threat condition presenting the target of discrimination as feminist increased perceptions of unfairness what, in consequence, triggered greater compassion.

Taken together these findings suggest that threats to the value of feminist identity (such as criticism of the feminist movement) can lead to greater differentiation between women with feminist (in-group members) versus conservative (out-group members) worldviews. This complements earlier findings by demonstrating the role of social categorization in shaping responses to gender discrimination (Dodd et al. 2001; Garcia et al. 2005, 2010; Schmitt et al. 2003). In line with previous research conducted in the U.S. (Dodd et al. 2001; Garcia et al. 2010; Kaiser et al. 2006; Schmitt et al. 2003), this experiment showed that in the Polish context in-group discrimination victims are responded to more positively than out-group members. Previous research pointed to in-group norms and situational ambiguity as factors modifying this effect (Garcia et al. 2005; Kaiser and Miller 2001). Our study distinguishes threats to group value as another moderator of the effect of social identity on responses to gender discrimination. In this study, although the manipulation check question suggested that the source of threat were other women, ideological inclinations of comments’ authors were not explicitly defined. Hence, they could have been perceived differently dependent on the experimental condition. Future research would do well to examine consequences of various sources of threat by manipulating them or controlling for their perceptions.

The present research also contributes to an improved understanding of the role of feminist identity in responses to discrimination. A study by Roy et al. (2009) conducted in the U.S. analyzed reactions to feminist and non-feminist women who complained (or not) about gender discrimination. Regardless of complaining, discrimination was less likely to be identified as a reason for the target’s negative outcome when she was presented as a feminist compared to when she was presented as non-feminist. According to authors, the feminist label might be related to discounting gender discrimination because feminists tend to be negatively stereotyped as being hypersensitive to sexism. In our study, feminist target of discrimination was responded to more positively. Hence, we propose that an alternative explanation of the results obtained by Roy et al. (2009) can be offered by social categorization theory (Turner et al. 1987). Because we have no information on the worldview of participants, it is at least conceivable that participants perceived the feminist as an out-group member and that this modified their perceptions of the situation. Thus, our research stresses the importance of taking into account the worldviews of participants while assessing attitudes toward feminist vs. non-feminist women.

Several alternative explanations for our results can be proposed. First, it is possible that a conservative woman, who might be less concerned with gender equality, would be perceived as deserving discrimination that “she asked for.” Therefore, the effect might be dependent not only on the in-group/out-group distinction but also on the specific stereotype of conservative women held by feminists (see also Roy et al. 2009). A second explanation is offered by in-group projection theory (Wenzel et al. 2003), which states that people tend to generalize typical in-group attributes to the superordinate category and that this tendency is strengthened under threat (an effect demonstrated in Germany by Ullrich et al. 2006). It is plausible that when faced with identity threat feminists were engaging in in-group projection by generalizing their feminist worldview to all women. Thus, they might have regarded women who do not share their views as less prototypical members of their gender group and seen the decision concerning a conservative woman as more deserved than those concerning a fellow feminist. Further studies are needed to investigate these possible mechanisms.

Our findings are likely to apply beyond feminism to other social movements that are frequent targets of criticism. An important challenge would be to discover ways to inoculate feminists, as well as other groups, from biased responses to identity threats. One approach is to examine forms of identification with their in-group. Recent research has distinguished between genuine and defensive group identification (Golec de Zavala et al. 2013). Defensive group identification can be seen in terms of collective narcissism—an emotional investment in an unrealistic belief about the unparalleled greatness of an in-group, accompanied by underlying doubts about group’s worth (Golec de Zavala et al. 2009). Defensive group identification is easily threatened and dependent on external validation, which has been demonstrated in various cultural contexts, including the U.S., UK, Poland, and Mexico (Golec de Zavala et al. 2009). In contrast, genuine mature in-group identification is a realistic, well-based pride of group’s positive characteristics (Golec de Zavala et al. 2013). It is seen as a group-level parallel of individual genuine self-esteem that is not easily threatened by criticism and does not provoke hostility in response to threat (see Bushman and Baumeister 1998). Such mature attachment to the in-group can serve as a buffer against threats and shape a more tolerant and inclusive group identity. Further research is needed to examine ways in which genuine group attachment develops. However, shaping such non-defensive feminist identity might be a step towards immunizing feminist (and other) movements to the effects of threat such as those reported in this study.

Conclusions and Implications

Feminist attitudes toward conservative female politicians such as Sarah Palin is a complex issue that might not only depend on support for gender equality in politics, but also on candidates’ standings on specific issues that are important to the feminist movement (e.g. abortion rights). However, the effectiveness of promoting social change towards greater gender equality depends largely on feminists’ ability to recognize gender discrimination when it takes place and react to it. In this study we identified threat and victim’s views as two factors that might influence this process. These findings have important implications for the feminist movement. Being aware of potential biases can inspire feminists to reevaluate their relationship with women that do not endorse feminist ideology. These results also shed new light on the ways backlash criticism affects feminists and their reactions to discrimination. Understanding these processes can hopefully be a first step to developing feminist identity that would be resilient to such threats. We hope that our findings will then prove useful for established as well as emerging feminist movements.

References

Ashmore, R. D., Deaux, K., & McLaughlin-Volpe, T. (2004). An organizing framework for collective identity: Articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 80–114. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.80.

Basińska, A. (2006). Czy kobiety są seksistkami? Etykieta feministki, praca w zawodzie typowo “męskim” lub “kobiecym” a percepcja dyskryminacji ze względu na płeć. [Can women be sexist? Feminist label, typically male or female jobs and gender-based discrimination.] (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland.

Batson, C. D. (1991). The altruism question: Toward a social-psychological answer. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Becker, J. C., & Wagner, U. (2009). Doing gender differently—the interplay of strength of gender identification and content of gender identity in predicting women’s endorsement of sexism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 487–508. doi:10.1002/ejsp.551.

Bliuc, A.-M., McGarty, C., Reynolds, K., & Muntele, D. (2007). Opinion-based group membership as a predictor of commitment to political action. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 19–32. doi:10.1027/1864-9335.39.1.37.

Branscombe, N. R., & Wann, D. L. (1994). Collective self esteem consequences of outgroup derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24, 641–657. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420240603.

Branscombe, N. R., Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (1999a). The context and content of social identity threat. In N. Ellemers, R. Spears, & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp. 35–58). Oxford: Blackwell.

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Harvey, R. D. (1999b). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135.

Breinlinger, S., & Kelly, C. (1994). Women’s responses to status inequality: A test of social identity theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18, 1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00293.x.

Burn, S. M., Aboud, R., & Moyles, C. (2000). The relationship between gender social identity and support for feminism. Sex Roles, 42, 1081–1089. doi:10.1023/A:1007044802798.

Bushman, B., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 219–229. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219.

Bystydzienski, J. M. (2001). The feminist movement in Poland: Why so slow? Women’s Studies International Forum, 24, 501–511. doi:10.1016/S0277-5395(01)00197-2.

Catalyst (2012a, January). Women in government. Retrieved from http://www.catalyst.org/file/562/qt_women_in_government%20(1).pdf.

Catalyst (2012b, March). Women in Europe. Retrieved from http://www.catalyst.org/file/582/qt_women_in_europe.pdf.

Cialdini, R. B., Schaller, M., Houlihan, D., Arps, K., Fultz, J., & Beaman, A. L. (1987). Empathy-based helping: Is it selflessly or selfishly mediated? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 749–758. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.749.

Cowan, G., Mestlin, M., & Masek, J. (1992). Predictors of feminist self-labeling. Sex Roles, 27, 321–330. doi:10.1007/BF00289942.

Daum, M. (2010, May 20). Saraha Palin, feminist. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com.

Dodd, E. H., Giuliano, T. A., Boutell, J. M., & Moran, B. E. (2001). Respected or rejected: Perceptions of women who confront sexist remarks. Sex Roles, 45, 567–577. doi:10.1023/A:1014866915741.

Doosje, B., Ellemers, N., & Spears, R. (1995). Perceived intragroup variability as a function of group status and identification. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31, 410–436. doi:10.1006/jesp.1995.101.

Douthat, R. (2010, June 13). No mystique about feminism. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com.

Duncan, L. E. (1999). Motivation for collective action: Group consciousness as mediator for personality, life experiences, and women’s rights activism. Political Psychology, 20, 611–635. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00159.

Eisele, H., & Stake, J. (2008). The differential relationship of feminist attitudes and feminist identity to self-efficacy. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 233–244. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00432.x.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (1997). Sticking together or falling apart: In-group identification as a psychological determinant of group commitment versus individual mobility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 617–626. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.3.617.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (2002). Self and social identity. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 161–186. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135228.

Frąckowiak-Sochańska, M. (2011). Postawy polskich kobiet wobec feminizmu. O samoograniczającej się świadomości feministycznej Polek. Attitudes of Polish women toward feminism. On the self-limiting feminist consciousness of Polish women. In E. Malinowska (Ed.), Folia Sociologica vol. 39. Społeczne konteksty i dylematy realizacji ról płciowych (pp. 149–170). Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

Garcia, D. M., Horstman Reser, A., Amo, R., Redersdorff, S., & Branscombe, N. R. (2005). Perceivers’ responses to in-group and out- group members who blame a negative outcome on discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 769–780. doi:10.1177/0146167204271584.

Garcia, D. M., Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., & Ellemers, N. (2010). Women’s reactions to ingroup members who protest discriminatory treatment: The importance of beliefs about inequality and response appropriateness. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 733–745. doi:10.1002/ejsp.644.

Gillis, S., Howie, G., & Munford, R. (2004). Introduction. In S. Gillis, G. Howie, & R. Munford (Eds.), Third wave feminism: A critical exploration (pp. 1–6). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Golec de Zavala, A., Cichocka, A. K., Eidelson, R., & Jayawickreme, N. (2009). Collective narcissism and its social consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 1074–1096. doi:10.1037/a0016904.

Golec de Zavala, A., Cichocka, A., & Bilewicz, M. (2013). The paradox of in-group love: Differentiating collective narcissism advances understanding of the relationship between in-group and out-group attitudes. Journal of Personality, 81, 16–28. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00779.x.

Graff, A. (2003). Lost between the waves? The paradoxes of feminist chronology and activism in contemporary Poland. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 4, 100–116. Retrieved from http://www.bridgew.edu/SoAS/JIWS/April03/Graff.pdf.

Graff, A. (2007). A different chronology: Reflections on feminism in contemporary Poland. In S. Gillis, G. Howie, & R. Munford (Eds.), Third wave feminism: A critical exploration (2nd ed., pp. 142–155). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Expanded.

Haddock, G., & Zanna, M. P. (1994). Preferring “housewives” to “feminists”: Categorization and the favorability of attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18, 25–52. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00295.x.

Hankiewicz, M. (2006). Kto się boi niestereotypowych kobiet? Wpływ nastawienia na karierę i etykiety feministki na zatrudnianie kandydatek na stanowisko kierownicze. [Who is afraid of counter stereotypical women? The influence of career choices and feminist label on hiring women for managerial positions]. (Unpublished master thesis). University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland.

Harding, K. (2010, May 26). 5 ways of looking at “Sarah Palin Feminism”. [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://jezebel.com/#!5548464/5-ways-of-looking-at-sarah-palin-feminism.

Hausmann, R., Tyson, L. D., & Zahidi, S. (2012). The global gender gap report 2011. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. doi:10.1080/03637750903310360.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Heitlinger, A. (1996). Framing feeminism in post-Communist Czech Republic. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 29, 17–93. doi:10.1016/S0967-067X(96)80013-4.

Henderson-King, D. H., & Stewart, A. J. (1994). Women or feminists? Assessing women’s group consciousness. Sex Roles, 31, 505–516. doi:10.1007/BF01544276.

Henderson-King, D. H., & Stewart, A. J. (1997). Feminist consciousness: Perspectives on women’s experience. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 415–426. doi:10.1177/0146167297234007.

Henderson-King, D. H., & Zhermer, N. (2003). Feminist consciousness among Russians and Americans. Sex Roles, 48, 143–155. doi:10.1023/A:1022403322131.

Holmes, A., & Traister, R. (2010, August 28). A Palin of our own. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com.

Jetten, J., Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Spears, R. (2001). Rebels with a cause: Group identification as a response to perceived discrimination from the mainstream. Personality Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1204–1213. doi:10.1177/0146167201279012.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (2004). Intergroup distinctiveness and differentiation: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 862–879. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.6.862.

Kaiser, C. R., & Miller, C. T. (2001). Stop complaining! The social costs of making attributions to discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 254–263. doi:10.1177/0146167201272010.

Kaiser, C. R., Dyrenforth, P. S., & Hagiwara, N. (2006). Why are attributions to discrimination interpersonally costly? A test of system and group justifying motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 1523–1536. doi:10.1177/0146167206291475.

Kamen, P. (1991). Feminist fatale: Voices from the “twentysomething” generation explore the future of the “women’s movement. New York: Donald I. Fine.

Karyłowski, J. (1982). Two types of altruistic behavior: Doing good to feel good or to make the other feel good. In V. Derlega & J. Grzelak (Eds.), Cooperation and helping behavior: Theories and research (pp. 397–413). New York: Academic.

Leung, K., Chiu, W., & Au, Y. (1993). Sympathy and support for industrial actions: A justice analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 781–787. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.78.5.781.

Libby, S. (2010, June 8). Fiorina vs. Boxer: The best female political showdown ever. What kind of “Year of the Woman” is this? Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/id/2256340.

Liss, M., O’Connor, C., Morosky, E., & Crawford, M. (2001). What makes a feminist? Predictors and correlates of feminist social identity in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 124–133. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.00014.

Major, B., Quinton, W. J., & McCoy, S. K. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of attributions to discrimination: Theoretical and empirical advances. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 251–330). San Diego: Academic.

Malinowska, E. (1995). Socio-political changes in Poland and the problem of sex discrimination. Women’s Studies International Forum, 18, 35–43. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(94)00078-6.

Marsh, R. (2009). Polish feminism in an east–west context. Women’s Writing Online, 1, 26–48. Retrieved from http://womenswriting.fi/files/2009/11/4_marsh.pdf.

Mathews, S. S., Horne, S. G., & Levitt, H. M. (2005). Feminism across borders: A Hungarian adaptation of Western feminism. Sex Roles, 53, 89–103. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-4281-x.

McGregor, I., & Jordan, C. H. (2007). The mask of zeal: Low implicit self-esteem, and defensive extremism after self-threat. Self and Identity, 6, 223–237. doi:10.1080/15298860601115351.

McGregor, I., Gailliot, M. T., Vasquez, N., & Nash, K. (2007). Ideological and personal zeal reactions to threat among people with high self-esteem: Motivated promotion focus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1587–1599. doi:10.1177/0146167207306280.

Morgan, B. L. (1996). Putting the feminism into feminism scales: Introduction of a liberal feminist attitude and ideology scale. Sex Roles, 34, 359–390. doi:10.1007/BF01547807.

Muller, D., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 852–863. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852.

Myaskovsky, L., & Wittig, M. A. (1997). Predictors of feminist social identity among college women. Sex Roles, 37, 861–883. doi:10.1007/BF02936344.

Nelson, J. A., Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., Hurt, M. M., Ramsey, L. R., Turner, D. L., et al. (2008). Identity in action: Predictors of feminist self-identification and collective action. Sex Roles, 58, 721–728. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9384-0.

Olson, J.E., Frieze, I.H., Wall, S., Zdaniuk, B., Ferligoj, A., Kogovsek, T., … Makovec, M.R. (2007). Beliefs in equality for women and men as related to economic factors in Central and Eastern Europe and the United States. Sex Roles, 56, 297–308. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9171-3.

Parker, A. (2010, November 6). 2010 Faltered as a new ‘Year of the Woman’ in politics. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. doi:10.1080/00273170701341316.

Ramsey, L. R., Haines, M. E., Hurt, M. M., Nelson, J. A., Turner, D. L., Liss, M., et al. (2007). Thinking of others: Feminist identification and the perception of others’ beliefs. Sex Roles, 56, 611–616. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9205-5.

Riek, B. M., Mania, E. W., & Gaertner, S. L. (2006). Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 336–353. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4.

Roy, R. E., Weibust, K. S., & Miller, C. T. (2009). If she’s a feminist it must not be discrimination: The power of the feminist label on observers’ attributions about a sexist event. Sex Roles, 60, 422–431. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9556-6.

Schmitt, M. T., Ellemers, N., & Branscombe, N. R. (2003). Perceiving and responding to gender discrimination in organizations. In S. A. Haslam, D. van Knippenberg, M. J. Platow, & N. Ellemers (Eds.), Social identity at work: Developing theory for organizational practice (pp. 277–292). New York: Psychology Press.

Simon, B., & Klandermans, B. (2001). Politicized collective identity: A social psychological analysis. American Psychologist, 56, 319–331. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.4.319.

Simon, B., Loewy, M., Stürmer, S., Weber, U., Freytag, P., Habig, C., … Spahlinger, P. (1998). Collective identification and social movement participation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 646–658. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.646.

Spears, R., Doosje, B., & Ellemers, N. (1999). Commitment and the context of social perception. In N. Ellemers, R. Spears, & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp. 59–83). Oxford: Blackwell.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In S. Worchel & L. W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., & Smith, P. M. (1984). Failure and defeat as determinants of group cohesiveness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 23, 97–111. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1984.tb00619.x.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Twenge, J. M., & Zucker, A. N. (1999). What is a feminist? Evaluations and stereotypes in closed-and open-ended responses. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 591–605. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1999.tb00383.x.

Ullrich, J., Christ, O., & Schluter, E. (2006). Merging on Mayday: Subgroup and superordinate identification as joint moderators of threat effects in the context of European Union’s expansion. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 857–876. doi:10.1002/ejsp.319.

Wall, B. (2010, October 26). What does Christine O’Donnell mean for feminism? [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://thefbomb.org/2010/10/what-does-christine-o%E2%80%99donnel-mean-for-feminism/.

Wenzel, M., Mummendey, A., & Waldzus, S. (2003). The ingroup as pars pro toto: Projection from the ingroup onto the inclusive category as a precursor to social discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 461–471. doi:10.1177/0146167202250913.

Williams, R., & Wittig, M. A. (1997). “I’m not a feminist, but…”: Factors contributing to the discrepancy between pro-feminist orientation and feminist social identity. Sex Roles, 37, 885–904. doi:10.1007/BF02936345.

Zucker, A. N. (2004). Disavowing social identities: What it means when women say, “I’m not a feminist, but….”. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 423–435. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00159.x.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Michał Bilewicz, Manana Jaworska, John Jost, Katie Greenaway, Jasia Pietrzak, Kasia Samson, Andrew Shipley, and Mikołaj Winiewski for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this paper and Eric Hehman, Marta Marchlewska, Karolina Oleksiak, and Marta Witkowska for their help with manuscript preparation. Preparation of this article was supported by University of Warsaw funding awarded to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cichocka, A., Golec de Zavala, A., Kofta, M. et al. Threats to Feminist Identity and Reactions to Gender Discrimination. Sex Roles 68, 605–619 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0272-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0272-5