Abstract

Gazelles (high-growth), unicorns (ventures valued at $1 billion), and decacorns (ventures valued at $10 billion) appear to be dominating the landscape of entrepreneurship. In 2021, there were more than 700 ventures that have been valued at $1 billion or more by venture capitalists, and there seems to be a continued trend in more arising. However, the facts show that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for over 90% of businesses and 50% of employment of the worldwide population, contributing up to 55% of GDP in developed economies. Thus, it is clear that in developed countries, small firms are the economy. However, the entire realm of entrepreneurship appears to drifting slowly away from the importance of smaller firms and focusing the entire emphasis on the relatively few tech giants. These giant corporations are now viewed through the prism of entrepreneurship. Thus, we ask quo vadis — where will the focus of entrepreneurship be post-COVID-19 — centralization or democratization? For researchers and policy makers, shedding some light on this question may help in the formulation of research agendas and policy directions.

Plain English Summary

Entrepreneurship is at a crossroads. Gazelles and unicorns (high growth ventures) are proliferating at a breathtaking pace yet, the true heartbeat of a vibrant economy is the growth of small and medium sized ventures. We ask the question: quo vadis-where are we going? In doing so we examine the proliferation of the fast growing “blitzscaled” ventures in comparison to the democratization of smaller entrepreneurial ventures. In other words, is the future about the few or the many? We further examine the threat against democracy and entrepreneurship in light of the recent Covid pandemic. One of the potentially powerful allies of the greater democratization of entrepreneurship is the enormous success of crowdfunding as a funding vehicle for even the smallest of startup enterprises. Our article concludes with a set of guiding lights for this crossroads because the vitality of the academic field of entrepreneurship must reflect the full vibrancy and plethora of manifestations of the underlying phenomenon of entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: quo vadis?

The foundation for economies worldwide is small business. Christopher Arnold, IFAC (2019)

As we witness a major upheaval due to the COVID-19 pandemic, what looms ahead for the world of entrepreneurship? What will the future hold for entrepreneurship based on the effects of the pandemic? Did the COVID-19 pandemic “zombify” smaller firms? Will there be an increased concentration of innovation by the powerful tech giants (e.g., Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Facebook) or a greater democratization of smaller firms increasing competition and innovation among the many? Entrepreneurship has been defined in many ways throughout the years. One definition encapsulates the essence of the term: “Entrepreneurship is a dynamic process of vision, change, and creation. It requires an application of energy and passion toward the creation and implementation of innovative ideas and creative solutions. Essential ingredients include the willingness to take calculated risks—in terms of time, equity, or career; the ability to formulate an effective venture team; the creative skill to marshal needed resources; the fundamental skill of building a solid business plan; and, finally, the vision to recognize opportunity where others see chaos, contradiction, and confusion” (Kuratko, 2020). The question that now resonates beyond the global pandemic seems to be one of “quo vadis — where are we going?”.

Shane (2009) argued that designing public policies which encourage more people to become entrepreneurs is counterproductive, and the exclusive focus should be high-growth ventures or gazelles. Shane (2009, p. 163) noted “we need to recognize that only a select few entrepreneurs will create businesses that…. create jobs, reduce unemployment, make markets more competitive, and enhance economic growth.” That argument seemed to take root, and as the years went by and the technology companies gained larger size, entrepreneurship began to be defined in terms of the focused few. Today disruptive innovations are driving the creation of numerous billion-dollar startups. The result has been a shift towards the centralization of powerful tech companies that control information and economic movement.

Yet, the facts show that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for over 90% of businesses and 50% of employment of the worldwide population, contributing up to 55% of GDP in developed economies (The World Bank, 2021). Thus, it is clear that in developed countries small firms are the economy. However, the entire realm of entrepreneurship appears to drifting slowly away from the importance of smaller firms and focusing the entire emphasis on the relatively few tech giants. These giant corporations are now viewed through the prism of entrepreneurship. Thus, we ask quo vadis — where will the focus of entrepreneurship be post-COVID-19 — centralization or democratization? For researchers and policy makers, shedding some light on this question may help in the formulation of research agendas and policy directions.

2 The proliferation of gazelles and unicorn ventures

Venture capitalists in Silicon Valley have focused on potential disruptive technologies with the goal of scaling fast for huge financial returns. A gazelle has been defined as a venture with at least 20 percent sales growth every year (for 5 years), starting with a base of at least $100,000. That term has been recognized for many years, but recently developed terms define a new type of aggressive scaling such as “unicorn” (a venture valued at $1 billion) and “decacorn” (a venture valued at $10 billion). “Blitzscaling” is another term now used for the funding mechanism for aggressive growth of a new venture, but it prioritizes speed over efficiency in the entrepreneurial world of uncertainty. While the risk is certainly always present with these blitzscaled ventures, many disruptive technology companies are growing faster than ever (Kuratko et al., 2020). In 2021, there were more than 700 ventures that have been valued at $1 billion or more by venture capitalists, and there seems to be a continued trend in more arising. As they continue to grow, many startups are surpassing the $1 billion level, and over 30 have achieved the $10 billion decacorn level, such as Facebook, Uber, and Airbnb. In 2021, Silicon Valley was home to three of the world’s five most valuable companies: Alphabet, Apple, and Facebook, valued together at almost $2.5 trillion. In terms of market capitalization, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Facebook, and Alibaba are included in the top 7 of all global companies. In 2020, VC investments totaled $130 billion supporting 6,022 firms. Unicorns were heavily favored by the VCs mega rounds of investments (Lee, 2021). Significantly, each major tech firm and each unicorn company started small as an entrepreneurial venture. Yet, there is a focus on these concentrated high-growth firms as the image of entrepreneurship.

Morris et al., (2015, p. 714) pointed out that this preoccupation with high-growth ventures has permeated the focus of entrepreneurship research: “What we might label the “dogma of high growth ventures” is reflected in the editorial policies of some of our leading journals (i.e., samples used in empirical research must focus on innovative or growth-seeking firms), case studies used in teaching entrepreneurship (e.g., Dropbox rather than a computer repair business), and a preoccupation with equity funding and especially venture capital firms (which fund less than 1% of start-ups) among scholars and educators.”

It is clear that the entrepreneurship discourse in the media and within entrepreneurial communities such as accelerators, incubators, and academic centers has been dominated by accounts of high-growth tech firms (Marvel, et al., 2020). These types of high-growth firms and venture capitalists focus on high-technology entrepreneurship have been discussed extensively in the literature (Basu et al., 2015; Lerner, 1995; Petty & Gruber, 2011; Rosenstein, 1988). With the venture capital industry emphasizing the blitzscaling of new ventures to secure rapid growth and garner major market share, will the post-COVID-19 era witness the continued proliferation of unicorns at the expense of the smaller ventures?

In a recent Delphi study of 175 entrepreneurship researchers about the future of entrepreneurship, a theme of “domination and polarization” surfaced. “Several respondents foresaw a future characterized by an increasing division and polarization between a relatively small number of entrepreneurial ventures that are extremely powerful and profitable and a relatively large number of entrepreneurial actors that have limited individual power and limited profits. In particular, large platforms are expected to dominate the innovation landscape, with platforms such as Amazon outperforming traditional retailers. Indeed, a majority of the panel believed that the major tech firms will vastly increase their power compared to today” (van Gelderen et al., 2021, p. 23).

3 Democratization of entrepreneurial ventures

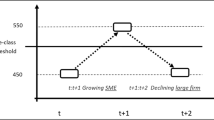

Davidsson (2005) argued that entrepreneurs create many different forms of ventures leading to a heterogeneous landscape. Morris et al. (2015) synthesized the commonalities among twenty different categorizations of venture startups appearing in the literature over a 50-year period to establish a typology of new ventures that included survival, lifestyle, managed growth, and aggressive or high-growth (HG) ventures. Morris et al. (2018) further examined these various types of ventures through the lens of identity theory to demonstrate the importance of their unique identities to the economy.

Morris and Kuratko (2020) delved deeper into the typology of ventures with their book, What Do Entrepreneurs Create?, which examined how entrepreneurs create a wide variety of businesses showing the need for a fundamental re-thinking of entrepreneurial activity by providing a foundation for developing theories of the four different types of entrepreneurial ventures. They contend that true economic vitality depends on a mix of venture types that complement the contributions of aggressive growth ventures. Here are some of the ways that survival, lifestyle, and managed growth ventures become critical to any economy: by stabilizing local economies through local employment, they become the economic backbone in many cities and towns; serving local market segments, which may be too small or insufficiently profitable to be served by aggressive growth or large companies; producing incremental innovations that can be develop product and process innovations; enabling the poor and lower middle classes to meaningfully improve their economic lot through the launch of the smaller ventures; and contributing to the fabric of communities by actively engaging with community groups and organizations, supporting local causes. The great and prescient insight of Morris and Kuratko (2020) was that it takes more than one type of entrepreneurship to constitute an entrepreneurial economy or society. It is inclusive entrepreneurship, spanning all the heterogeneous types with their varied manifestations, that translates into an entrepreneurial economy.

More significantly, Morris and Kuratko (2020) argued that the current research and teaching in entrepreneurship failed to distinguish the different types of entrepreneurial ventures. This failure resulted in major challenges for entrepreneurial researchers as well as those attempting to foster entrepreneurship through ecosystems comprised of economic development, public policies, community organizations, and universities. Thus, they advocated for the adoption of a portfolio approach when developing entrepreneurial ecosystems that recognize the distinctiveness of survival, lifestyle, managed growth, and aggressive growth businesses. The future of the global entrepreneurial landscape depends on this recognition.

Can the post-COVID-19 environment resuscitate the smaller ventures across the economy and rejuvenate a surge in entrepreneurial startups through the existing entrepreneurial ecosystems (Kuratko et al., 2017)? More significantly, will there be an avenue for the increased democratization of entrepreneurship versus the proliferation of only unicorns at the expense of other types of entrepreneurship? Will the immediate future enhance or constrain the entrepreneurial mindset for this generation (Kuratko et al., 2021).

In the recent Delphi study of entrepreneurship researchers about the future of entrepreneurship, there appeared to be support for a proliferation of smaller ventures in what was termed, “everyday-everyone” entrepreneurship. The study showed that many researchers believed that this “everyday-everyone” entrepreneurship will be supported by a variety of technologies such as social media and crowdfunding, which will provide tools and connectivity. The researchers also believed that the increase in entrepreneurship education and training will add to this increase in entrepreneurship. “As such, democratization of technology and knowledge will empower individuals to see/create and act on opportunities, to solve problems, and to innovate. Empowered individuals may even tackle wicked problems and grand challenges….It was proposed that, by 2030 everyday-everyone entrepreneurship will attract more media and research attention than high-growth entrepreneurship….” (van Gelderen et al., 2021, p.23).

4 Entrepreneurship and democracy threatened

Unicorns are fast becoming powerful entities across the globe. As an example, Google possesses more information about people than any entity ever before. Its business model demonstrates a continuation of personal information collection at an increasing pace while providing less transparency about its activities. “Despite its mantra – “Don’t be evil” – Google’s ever-growing power calls for keeping a close eye on the company, just as it is keeping a close eye on us” (Public Citizen, 2014, p. 3). As this early warning notice came back in 2014, Google (now known under the parent name of Alphabet) has grown exponentially. Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft have all accomplished similar exponential growth.

In a point/counterpoint article, Davis (2021, p. 4) discusses how the concept of a corporate purpose needs democracy with an example from the tech world, “Social media, once seen as a harmless distraction, has grown to be a potential threat to people’s well-being, and perhaps even to democracy itself. Facebook and similar platforms are engineered to promote compulsive usage through a variety of “variable reinforcement” rewards. Studies have shown Facebook’s potentially deleterious effects on depression and anxiety, particularly among the young (e.g., Kross et al., 2013). Moreover, Facebook has served as a vehicle to enable campaigns of ethnic persecution and election hacking, all for the purpose of selling ads. As Shoshana Zuboff (2019) describes in clinical detail, social media and other tech companies have ushered in a new era of “surveillance capitalism,” which is at least as sinister as it sounds.”

As these focused few firms gain more power over the populace and influence with the government, the roots of democracy and entrepreneurship become threatened. In their thorough and insightful analysis, Audretsch and Moog (2021, p. 2) clearly demonstrated the link between democracy and entrepreneurship as they succinctly state, “Because democracy reflects freedom, it also is conducive to the ability of people and organizations both to engage in behavior and activities to discover and create opportunities as well as to act on and pursue those opportunities (Lazear, 2005)… Although they are not linked together in any systematic or formal manner in the entrepreneurship literature, both democracy and entrepreneurship share the same underlying force or context. Just as a vast literature has found that entrepreneurship requires a context to make free choices in both thought and action (Bradley & Klein, 2016), so too does the freedom of thought and action serve as a cornerstone for democracy (Dahl, 1998).”

More significantly, Audretsch and Moog (2021, p. 15) cautioned as to the impact that COVID-19 has had when they stated, “The Covid-19 crisis has greatly exacerbated concerns about both the demise of democracy and the decline of entrepreneurship. This is because Covid-19 adversely impacted the underlying force that links democracy to entrepreneurship–the ability of people to engage in free choice with an absence of authoritarian restrictions. The Covid-19 crisis has provided legitimacy to totalitarian politics centralizing economic decision-making…”.

More scholars are recognizing the serious negative impacts of COVID-19 as Muzio and Doh (2021, p. 5) state, “COVID-19 has suddenly and dramatically halted what seemed to be the inexorable rise of the ‘market logic’ and almost overnight displaced this with the values, discourses, and practices connected with alternative logics such as those of the ‘state’ and the ‘community’ (Thornton et al., 2012). In particular, the State has reasserted its central role across all economic and societal sectors, by imposing unprecedented levels of regulations and shutting down whole sectors (hospitality) whilst seeking to rapidly expand others through state intervention, increased funding and deregulation (medical research, healthcare, online education) (King & Carberry, 2020; Lawton et al., 2020). Furthermore, through the various subsidy and furlough schemes, the ‘frontiers of the state’, to reverse Margaret Thatcher’s famous expression, have been rolled forward to the point, that even in market oriented countries such as the UK, half of the workforce now directly depends on state employment or subsidy (Telegraph, 2020). Whilst across the media and public discourse the priorities of economic growth, solidarity and freedom of enterprise are subordinated to those of safety, collective wellbeing and community cohesion.”

If democracy becomes further eroded through heavy government regulation and control, then how exactly would smaller ventures survive in the midst of growing gazelles and unicorns? It becomes a sobering thought as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic that crippled so much of the world economy.

In the van Gelderen et al. (2021) study, some researchers claimed that the power of global mega-corporations was increasing, and therefore, individual respondents proposed that country sovereignty and individual privacy may be increasingly threatened. However, on a more positive note, the belief that this would emerge was not accepted by the majority of researchers.

5 The state of entrepreneurship post-COVID-19

The 2020/2021 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) showed evidence that due to the pandemic entrepreneurs in Europe, America, and Latin American suffered substantial negative impacts, while Asian markets were overall more positively impacted because they were needed as suppliers of essential products and technologies (Bosma et al., 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic had a horrific impact on small businesses in the USA. While small businesses either closed their doors or saw their revenues plunge dramatically, some of the biggest companies in the USA (like Amazon and Walmart) witnessed a financial boost in billions of dollars. In addition, other blitzscaled firms like Google, Facebook, and Apple continued to grow at exponential rates. Experts say that there are three major reasons why larger firms were breaking financial records while small businesses floundered during the pandemic: financial positioning, lobbying power, and tech investments (Taylor, 2021).

Entrepreneurship, along with homeownership, is one of the most prominent ways for Americans to build wealth. But, small businesses are making up less and less of the economy. During the COVID-19 pandemic minority-owned businesses were disproportionately impacted as so many small firms found it increasingly challenging to compete or even remain open. As small businesses vanish, it leaves many people of color — already with less generational wealth than white families — with one fewer option to build wealth (Rodriguez-Zaba, 2021). Yet, it has been shown that entrepreneurship can be a viable pathway out of poverty (Banerjee & Duflo, 2007; Bruton et al., 2013; Sutter et al., 2019). Across the world, poverty entrepreneurs start millions of smaller ventures each year (Slivinski, 2012). The revenue generated from these ventures allows them to escape poverty and become less dependent on public and private forms of support (Edelman, et al., 2010). In addition, establishing a new venture can contribute to enhanced self-efficacy, skill development, self-identity, pride, dignity, and ability to give back to the community (Morris & Tucker, 2020; Shantz et al., 2018). However, while all entrepreneurs must overcome the liabilities of newness and smallness as they attempt to launch and grow a new venture, those potential entrepreneurs in poverty face an even greater challenge due to a concept introduced by Morris et al. (2021), known as the “liability of poorness,” which centers on literacy gaps, a scarcity mindset, intense non-business pressures, and the lack of a safety net. Each of these components of the liability of poorness contributes to the disadvantage and fragility of the enterprises confronting the poor. Rather than dismissing smaller ventures as unimportant, they should be embraced by any society seeking to eradicate poverty.

The bright light of hope relates to the history of how entrepreneurs rose up in past economic crises to drive recovery. As stated in the latest Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report, “….individuals that are currently making the decision to start and/or to grow a business are ultimately creating jobs and incomes, adding value to society and strengthening economies. In other words, much as vaccination is the key to global health recovery, so too is entrepreneurship the key to unlocking worldwide economic recovery” (Bosma et al., 2021 p.13). Further, the growth of equity crowdfunding may become a needed solution to the preoccupation of venture capitalists with gazelles and unicorns as the key to entrepreneurship.

6 Crowdfunding: democratizing venture investments

In order for new ventures to rise up as well as previously closed small firms to survive and prosper, crowdfunding may be the best vehicle to change the landscape of entrepreneurship. In recent years, the growth of crowdfunding has been immense, and the statistics appear to validate its prevalence. For example, in 2019, there were 1,616 crowdfunding platforms in the USA, 99 in Canada, and 135 in Latin America (Technavio, 2021). Crowdfunding, according to various sources, is predicted to grow by $196 billion during 2021–2025. The global crowdfunding market was calculated to be at $17.2 billion in 2020 and is determined to reach $300 billion by 2030, garnering a compound annual growth rate of 16% between 2020 and 2025.

Blevins et al., (2017, p. 120) note that new crowdfunding processes have the potential to alter “the relationship between the risk these ventures traditionally take on and the returns they need to generate in exchange for taking on such risks.” Drover et al. (2017) and McKenny et al. (2017) have called for more scholarly research within this new realm of startup investing to reveal the extent to which it has the power to provide newer and more efficient funding avenues for entrepreneurs.

The emergence of equity crowdfunding has created tremendous potential for individual investors and new entrepreneurial startups. Equity crowdfunding has been gaining popularity because there is an equity stake in the new venture provided by the entrepreneur in exchange for the money pledged (Cholakova & Clarysse, 2015). It is interesting to note that public equity fundraising by startups had been enforced as an illegal practice in the USA since 1933. However, in 2012, the US Congress passed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act, which included a Crowdfund provision. This act allowed equity crowdfunding to be legal and encouraged (Stemler, 2013). The JOBS act legislation and Regulation Crowdfund effectively made it legal for any US startup to raise funds from any individual without the legal requirement of public offering filings. The SEC issued Regulation D in 1982, which provides a series of rules guiding private — as opposed to public — offerings. The JOBS Act, created a new kind of offering under Regulation D, codified in Rule 506(c), which is in effect known as Title II Crowdfunding. The basic regulations allow an unlimited amount of money raised; an unlimited number of accredited investors (but no unaccredited investors); exemption from state Blue Sky registration (state securities regulation); and allowance of general solicitation and advertising (Securities and Exchange Commission, 2021).

Individually, crowdfunders tend to be geographically dispersed and often invest only modest amounts of capital in comparison to venture capitalists who routinely invest millions in a single transaction. The crowdfunding model has three principal parts: the entrepreneur who proposes the idea and/or venture to be funded; individuals or groups who support the idea; and a moderating organization (the “platform”) that brings the parties together to launch the idea (Kuratko, 2020). Thus, scholars have noted that crowdfunding has the potential to democratize the new venture fundraising process by allowing the general public to get involved in early-stage funding (Stevenson et al., 2019).

7 Guiding lights for entrepreneurship in the future

Entrepreneurship stands at the crossroads. In terms of the phenomenon itself, will it continue to shift increasingly towards the exceptional and extraordinary, such as unicorns and blitzscalers, so that it eventually becomes a privilege of the few, rather than a possibility for the many? Empirical evidence continues to mount across a broad spectrum of institutional and national contexts that entrepreneurship for the crowd is diminishing, even as it concentrates among the few (Audretsch & Moog, 2021).

The academic field of and research on entrepreneurship is similarly at a pivotal juncture. Will it remain true to its roots, reflecting the breadth and diversity of the phenomenon itself, along with its bountiful multitude of manifestations? Or will it succumb to those voices and forces prioritizing the few, albeit the most visible and successful, at least measured by one dimension?

One thing is for sure. The vitality of the academic field of entrepreneurship is not at all guaranteed and will continue to thrive and prosper until to the extent that it reflects the full vibrancy and plethora of manifestations of the underlying phenomenon itself. The history of scientific and academic research is replete with precedents of the dismal decline awaiting any applied field, such as entrepreneurship, that has lost touch with the real-world phenomenon it is trying to explain and understand (Kuhn, 1962).

In fact, the academic field of entrepreneurship not only reflects the underlying phenomenon, but also can ultimately influence and shape it by the way it influences thinking in business and policy. As the great scholar, John Maynard Keynes (1936) observed, nearly a century ago, what holds in economics is no less valid for entrepreneurship, “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually slaves of some defunct economist.” There are compelling reasons to think, and even fear, the consequences of entrepreneurship for the few rather than for the many. As Audretsch and Moog (2021) point out, a paucity of entrepreneurship is linked to an alarming threat to democracy.

Perhaps the best way to ensure that the field reflects entrepreneurship for the many and not just the few is to follow the conclusion of Morris and Kuratko (2020) that, in fact, entrepreneurship is not one thing, so that the search for a sole manifestation of entrepreneurship is misguided. Rather, Morris and Kuratko (2020) suggest that such debates are pointless and they are looking for the true meaning of entrepreneurship in the wrong place. Rather, as they suggest, there are four different types or manifestations of entrepreneurship, which can be theoretically and empirically differentiated. Just as importantly, they conclude that, given the heterogeneity of social and individual goals and preferences, a portfolio of all types of entrepreneurship may best serve society. The current state of research in entrepreneurship has surprisingly little to say about the interactions and linkages among various types of entrepreneurship, particularly when viewed through a dynamic lens.

The question remains as to where the field of entrepreneurship is headed (quo vadis)? According to some researchers in the van Gelderen et al. (2021) study, “entrepreneurship will become more necessity focused, directed at frugal innovation, low-tech services, as well as social ventures addressing social and environmental challenges in a local manner. These respondents suggested that there will be many startups, but these startups will find growth more difficult given that much of “the pie” is already flowing to a few large dominant firms” (p. 24). However, to move forward towards the future, we need some “guiding lights” to show the potential ways ahead.

Will this be the case in the future or will the “everyday-everyone” entrepreneurs supported by new technologies empower individuals to create new ventures to solve problems and to innovate in all aspects of life? One guiding light may be that individual entrepreneurs will exhibit greater entrepreneurial hustle to make their ventures succeed in spite of the odds. Fisher et al. (2020) define entrepreneurial hustle as, “an entrepreneur’s urgent, unorthodox actions that are intended to be useful in addressing immediate challenges and opportunities under conditions of uncertainty” (1002). The future poses greater uncertainty than ever before, so the concept of entrepreneurial hustle will be a needed element.

The rapid expansion of crowdfunding appears to be another guiding light for the future. With the power of everyday people to invest in newly created venture concepts, there exists far greater opportunities for entrepreneurs in every industry to rise and grow. The immense expansion of equity crowdfunding has already demonstrated the potential for this relatively new funding source to help proliferate individual entrepreneurs (Shepherd, 2021).

The rising importance of “coaching” entrepreneurs in the realm of accelerators is indicative of another guiding light. Research studies have been emerging touting the importance of the coachability of entrepreneurs in raising funding and gaining legitimacy with their ventures (Kuratko et al., 2021; Marvel et al., 2020).

Another possible guiding light might be found in future “partnerships.” It could be that entrepreneurial gazelles and unicorns in the technology world will seek to work with smaller startups in “partnership” arrangements (for example, the recent partnership between GAP and Walmart to launch Gap Home, a Gap-branded home décor, bedding, and bath collection) (Kavilanz, 2021). Could this be a trend that begins to take root? In other words, the best of both worlds arise. Unicorns and decacorns continue to develop, but the landscape of smaller entrepreneurial ventures of all sizes (Morris & Kuratko, 2020) will become far more dominant throughout nations.

While there are numerous potential entrepreneurial pathways ahead, our suggested guiding lights may offer some solutions. It is our fervent belief that how this crossroads is handled will eventually determine the future of entrepreneurship. Quo vadis — where are we going? Let us hope the answer infuses the entrepreneurial mindsets of individuals for a vibrant future (Kuratko et al., 2021).

References

Arnold, C. (2019). The foundation for economies worldwide is small business. International Federation of Accountants, June 26. Retrieved on April 11, 2021. https://www.ifac.org/knowledge-gateway/contributing-global-economy/discussion/foundation-economies-worldwide-small-business-0

Audretsch, D. B., & Moog, P. (2021). Democracy and entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, in-Press. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720943307

Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2007). The economic lives of the poor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 141–167.

Basu, S., Sahaym, A., Howard, M. D., & Boeker, W. (2015). Parent inheritance, founder expertise, and venture strategy: Determinants of new venture knowledge impact. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 322–337.

Blevins, D. P., Ragozzino, R., & Reuer, J. J. (2017). How the Jobs Act is reshaping IPOs: Implications for entrepreneurial firms. Academy of Management Perspectives, 31(2), 109–123.

Bosma, N., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelley, D., Guerrero, M, & Schott, T. (2021). 2020/2021 Global report. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Babson College, Wellesley, MA.

Bradley, S. W., & Klein, P. (2016). Institutions, economic freedom, and entrepreneurship: The contribution of management scholarship. Academy of Management Perspectives, 30(3), 211–221.

Bruton, G. D., Ketchen, D. J., Jr., & Ireland, R. D. (2013). Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(6), 683–689.

Cholakova, M., & Clarysse, B. (2015). Does the possibility to make equity investments in crowdfunding projects crowd out reward-based investments? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(1), 145–172.

Dahl, R. A. (1998). On democracy. Yale University Press.

Davidsson, P. (2005). Researching entrepreneurship (Vol. 5). Springer Science & Business Media.

Davis, G. F. (2021). Corporate purpose needs democracy. Journal of Management Studies, in-Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12659

Drover, W., Busenitz, L., Matusik, S., Anglin, A., & Dushnitsky, G. (2017). A review and road map of entrepreneurial equity financing research: Venture capital, corporate venture capital, angel investment, crowdfunding, and accelerators. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1820–1853.

Edelman, L. F., Brush, C. G., Manolova, T. S., & Greene, P. G. (2010). Start-up motivations and growth intentions of minority nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(2), 174–196.

Fisher, G., Stevenson, R., Burnell, D., Neubert, E., & Kuratko, D. F. (2020). Entrepreneurial hustle: Navigating uncertainty and enrolling venture stakeholders through urgent and unorthodox action. Journal of Management Studies, 57(5), 1002–1036.

Kavilanz, P. (2021). Gap is launching a home line through Walmart. CNN Business, May 26. Accessed online at https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/26/business/gap-walmart-home/ )

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. Palgrave MacMillan.

King, B. G., & Carberry, E. J. (2020). Movements, societal crisis, and organizational theory. Journal of Management Studies, 57, 1741–1745.

Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., Shablack, H., Jonides, J., & Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One, 8, e69841.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Kuratko, D. F. (2020). Entrepreneurship: Theory, process, practice (11th ed.). Cengage.

Kuratko, D. F., Fisher, G., & Audretsch, D. B. (2021). Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset. Small Business Economics, in Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00372-6

Kuratko, D. F., Holt, H., & Neubert, E. (2020). Blitzscaling: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Business Horizons, 63(1), 109–119.

Kuratko, D.F., Neubert, E., & Marvel, M.R. (2021). Insights on the mentorship and coachability of entrepreneurs. Business Horizons, 64(2), 199–209

Kuratko, D. F., Fisher, G., Bloodgood, J., & Hornsby, J. S. (2017). The paradox of new venture legitimation within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 119–140.

Lawton, T. C., Dorobantu, S., Rajwani, T. S., & Sun, P. (2020). The implications of COVID-19 for nonmarket strategy research. Journal of Management Studies, 57, 1732–1736.

Lazear, E. P. (2005). Entrepreneurship. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(4), 649–680.

Lee, J.H. (2021). Venture capital hits record high in U.S. in 2020 despite pandemic. Reuters, January 8. Retrieved online https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venture-capital-data/venture-capital-hits-record-high-in-u-s-in-2020-despite-pandemic-idUSKBN29D0IR

Lerner, J. (1995). Venture capitalists and the oversight of private firms. Journal of Finance, 50(1), 301–318.

Marvel, M. R., Wolfe, M. T., & Kuratko, D. F. (2020). Escaping the knowledge corridor How founder human capital and founder coachability impacts product innovation in new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(6), 106060.

McKenny, A. F., Allison, T. H., Ketchen, D. J., Short, J. C., & Ireland, R. D. (2017). How should crowdfunding research evolve? A survey of the entrepreneurship theory and practice editorial board. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(2), 291–304.

Morris, M.H., Kuratko, D.F. (2020). What do entrepreneurs create? Understanding different venture types. (Edward Elgar Press).

Morris, M. H., Neumeyer, X., & Kuratko, D. F. (2015). A portfolio perspective on entrepreneurship and economic development. Small Business Economics, 45(4), 713–728.

Morris, M. H., Neumeyer, X., Jang, Y., & Kuratko, D. F. (2018). Distinguishing types of entrepreneurial ventures: An identity-based perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(3), 453–474.

Morris, M. H., & Tucker, R. (2020). Poverty and entrepreneurship in developed economies: Re-assessing the roles of policy and community action. Journal of Poverty, 1–22.

Morris, M. H., Kuratko, D. F., Audretsch, D. B., & Santos, S. (2021). Overcoming the liability of poorness: Disadvantage, fragility and the poverty entrepreneur. Small Business Economics in Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00409-w

Muzio, D. & Doh, J. (2021). COVID-19 and the future of management studies. Insights from leading scholars. Journal of Management Studies, In Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12689

Petty, J. S., & Gruber, M. (2011). In pursuit of the real deal: A longitudinal study of VC decision making. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(2), 172–188.

Public Citizen. (2014). Mission Creep-y: Google is quietly becoming one of the nation’s most powerful political forces while expanding its information-collection empire. Public Citizen Report (Public Citizen’s Congress Watch, Washington, DC), November.

Rodriguez-Zaba, D. (2021). How minority-owned businesses can thrive during (and after) Covid-19. Forbes, February 18. Retrieved at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2021/02/18/how-minority-owned-businesses-can-thrive-during-and-after-covid-19/?sh=8d67d194b459

Rosenstein, J. (1988). The board and strategy: Venture capital and high technology. Journal of Business Venturing, 3(2), 159–170.

Securities and Exchange Commission (2021). Regulation D. electronic code of federal regulations: 17 CFR 230.501 - 230.508. http://www.ecfr.gov/ Accessed 28 May 2021.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149.

Shantz, A. S., Kistruck, G., & Zietsma, C. (2018). The opportunity not taken: The occupational identity of entrepreneurs in contexts of poverty. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(4), 416–437.

Shepherd, M. (2021). Crowdfunding statistics (2021): Market size and growth. Fundera, Retrieved at: https://www.fundera.com/resources/crowdfunding-statistics

Slivinski, S. (2012). Increasing entrepreneurship is a key to lowering poverty rates. Policy Report, Goldwater Institute, 254, November 13, 2012.

Stevenson, R. M., Kuratko, D. F., & Eutsler, J. (2019). Crowdfunding and the democratization of new venture investments: Unleashing mainstreet entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 375–393.

Stemler, A. R. (2013). The JOBS Act and crowdfunding: Harnessing the power-and money-of the masses. Business Horizons, 56(3), 271–275.

Sutter, C., Bruton, G. D., & Chen, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(1), 197–214.

Taylor, K. (2021). In 2020, big businesses got bigger and small businesses died. The vicious cycle won’t stop until we take action. Business Insider, January 3. Retrieved at: https://www.businessinsider.com/in-2020-big-businesses-got-bigger-small-businesses-died-2020-12

Technavio. (2021). Crowdfunding market by type and geography - Forecast and analysis 2021–2025. February. Retrieved at: https://www.technavio.com/report/crowdfunding-market-industry-analysis

Telegraph (2020). More than half of all adults now paid by the state. Available at https://www.teleg raph.co.uk/busin ess/2020/05/04/half-adults-now-paid-state/(accessed 19 January 2020).

The World Bank. (2021). Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) finance. Retrieved at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance

Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective. Oxford University Press.

van Gelderen, M., Wiklund, J. & McMullen, J.S. (2021). Entrepreneurship in the future: A Delphi study of ETP and JBV editorial board members. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, In Press (1–37).

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Public Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuratko, D.F., Audretsch, D.B. The future of entrepreneurship: the few or the many?. Small Bus Econ 59, 269–278 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00534-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00534-0