Abstract

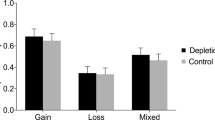

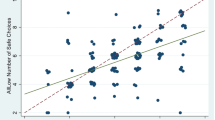

The “general risk question” (GRQ) has been established as a quick way to meaningfully elicit subjective attitudes toward risk and correlates well with real-world behaviors involving risk. However, little is known about what aspects of attitudes toward financial risk are captured by the GRQ. We examine how answers to the GRQ correlate with different preference motives and biases toward financial risk using an incentivized choice task (n = 1,730). We find that the GRQ has meaningful correlation with loss aversion and attitudes toward variation in financial losses, but much weaker to non-existent correlations with attitudes toward variation in financial gains, likelihood insensitivity, and certainty preferences. These results suggest that practical applications using the GRQ as an index for financial risk preferences may be most appropriate in settings where decisions rest on attitudes toward financial losses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Specifically, the GRQ asks respondents to rate their own willingness to take risks on a scale of 0 (not at all willing) to 10 (very willing). Our translation of Dohmen et al.’s original GRQ (from German) is displayed in Fig. 1.

Specifically, when only considering the gain domain, the model nests expected utility theory, rank dependent expected utility and the dual theory of Yaari (1987). The prospect theory functional also acts very similar to the reference-dependent preference model of Köszegi and Rabin (2007) in surprise gambles which are arguably the correct model for lottery decisions in experiments. The model does, however, not allow for eliciting preference of certain other models, such as regret theory (Bell 1982).

For the exact technical assumptions, refer to Online Appendix A.

v(0) = u(0) needs to be maintained such that a preference for certainty can exist within the framework of cumulative prospect theory.

The order of the risk preference elicitation tables was randomized. Additionally, we randomized whether the safe choices were displayed on the left or on the right and whether payments and probability were vertically increasing or decreasing.

In a slight abuse of terminology, we henceforth refer to these measures of preference motives as “preference scales.” For ease of reference, the calculations for all preference scales are also given in the captions of Fig. 2. We provide detailed proofs supporting our construction of these preference scales in Online Appendix A.

The analysis of those insurance choices and their link to preference measures is the focus of a separate research paper. That paper does not analyze the correlations with GRQ.

In compliance with local laboratory standards regarding hourly wages, university subjects were also paid a flat show-up fee of $6.00. This payment was not disclosed until the end of the experiment. No additional payments were made to mTurk subjects.

This pattern is not a product of randomizing the direction of the GRQ response scale. Both the group that answered on a 0-10 scale and the group that answered on a 10-0 scale show a bimodal pattern of responses.

Specifically, our measure of loss aversion ranges from 0 to 21, while the other preferences are on a 33-point scale (UC measures are 0 to 32, while LI and CP are -16 to 16). GRQ is on an 11-point scale (0 to 10). To address this in our analysis, we standardize GRQ and the preference scales by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation, denoting these standardized values with the subscript std. We evaluate the correlations and regression coefficients as shifts in standard deviation rather than comparing unit changes of unequal measure.

Callen et al. (2014), for example, report that 69% of their subjects switched in the same row after excluding dominance-violating choices. Our GD or LD tables show this pattern in less than 20% of the cases.

There is a substantial literature showing the gender effect on risk preferences. See Charness and Gneezy (2012) for a meta analysis.

In the experiment, the “Next” button was hidden for 20 seconds on each lottery page to encourage thoughtful consideration of the lottery choices (and to prevent subjects from clicking through as soon as the page loads). The subsample in column (1) thus includes only subjects who always took at least 5 seconds more than the minimum requirement.

References

Andersson, O., Holm, H.J., Tyran, J.-R., & Wengström, E. (2016). Risk aversion relates to cognitive ability: Preferences or noise? Journal of the European Economic Association, 14(5), 1129–1154.

Barseghyan, L., Molinari, F., O’Donoghue, T., & Teitelbaum, J.C. (2013). The nature of risk preferences: Evidence from insurance choices. American Economic Review, 103(6), 2499–2529.

Bell, D.E. (1982). Regret in decision making under uncertainty. Operations Research, 30(5), 961–981.

Callen, M., Isaqzadeh, M., Long, J.D., & Sprenger, C. (2014). Violence and risk preference: Experimental evidence from Afghanistan. American Economic Review, 104(1), 123–148.

Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2012). Strong evidence for gender differences in risk taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83(1), 50–58.

Charness, G., Gneezy, U., & Imas, A. (2013). Experimental methods: Eliciting risk preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 87, 43–51.

Csermely, T., & Rabas, A. (2016). How to reveal people’s preferences: Comparing time consistency and predictive power of multiple price list risk elicitation methods. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 53(2-3), 107–136.

Decker, S., & Schmitz, H. (2016). Health shocks and risk aversion. Journal of Health Economics, 50, 156–170.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G.G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550.

Etchart-Vincent, N., & l’Haridon, O. (2011). Monetary incentives in the loss domain and behavior toward risk: An experimental comparison of three reward schemes including real losses. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 42(1), 61–83.

Evans, W.N., & Viscusi, W.K. (1991). Estimation of state-dependent utility functions using survey data. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 73(1), 94–104.

Gigerenzer, G., & Hoffrage, U. (1995). How to improve Bayesian reasoning without instruction: Frequency formats. Psychological Review, 102(4), 684.

Gómez-Mejía, L.R., Haynes, K.T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K.J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137.

Hara, K., Adams, A., Milland, K., Savage, S., Callison-Burch, C., & Bigham, J.P. (2018). A data-driven analysis of workers’ earnings on Amazon Mechanical Turk. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery.

Harbaugh, W.T., Krause, K., & Vesterlund, L. (2010). The fourfold pattern of risk attitudes in choice and pricing tasks. The Economic Journal, 120 (545), 595–611.

Hershey, J.C., & Schoemaker, P.J. (1985). Probability versus certainty equivalence methods in utility measurement: Are they equivalent? Management Science, 31(10), 1213–1231.

Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 65–70.

Huber, C., & Huber, J. (2019). Scale matters: Risk perception, return expectations, and investment propensity under different scalings. Experimental Economics, 22(1), 76–100.

Jaspersen, J., & Peter, R. (2017). Experiential learning, competitive selection and downside risk: A new perspective on managerial risk-taking. Organization Science, 28(5), 915–930.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Koonce, L., McAnally, M.L., & Mercer, M. (2005). How do investors judge the risk of financial items? The Accounting Review, 80(1), 221–241.

Köszegi, B., & Rabin, M. (2007). Reference-dependent risk attitudes. American Economic Review, 97(4), 1047–1073.

Koudstaal, M., Sloof, R., & Van Praag, M. (2015). Risk, uncertainty, and entrepreneurship: Evidence from a lab-in-the-field experiment. Management Science, 62(10), 2897–2915.

Lönnqvist, J.-E., Verkasalo, M., Walkowitz, G., & Wichardt, P.C. (2015). Measuring individual risk attitudes in the lab: Task or ask? An empirical comparison. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 119, 254–266.

March, J.G., & Shapira, Z. (1987). Managerial perspectives on risk and risk taking. Management Science, 33(11), 1404–1418.

Rothschild, M., & Stiglitz, J.E. (1970). Increasing risk: I. a definition. Journal of Economic Theory, 2(3), 225–243.

Schmidt, U. (1998). A measurement of the certainty effect. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 42(1), 32–47.

Šidák, Z. (1967). Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 62(318), 626–633.

Tanaka, T., Camerer, C.F., & Nguyen, Q.D. (2010). Risk and time preferences: Linking experimental and household survey data from Vietnam. American Economic Review, 100(1), 557–571.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323.

Vieider, F.M. (2018). Certainty preference, random choice, and loss aversion: A comment on “Violence and Risk preference: Experimental Evidence from Afghanistan”. American Economic Review, 108(8), 2366–2382.

Vieider, F.M., Lefebvre, M., Bouchouicha, R., Chmura, T., Hakimov, R., Krawczyk, M., & Martinsson, P. (2015). Common components of risk and uncertainty attitudes across contexts and domains: Evidence from 30 countries. Journal of the European Economic Association, 13(3), 421–452.

Wang, C.X., & Webster, S. (2009). The loss-averse newsvendor problem. Omega, 37(1), 93–105.

Yaari, M.E. (1987). The dual theory of choice under risk. Econometrica, 55(1), 95–115.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation for financial support under grant number G-2016-7312. For helpful feedback and comments, we are indebted to Sebastian Ebert, Ferdinand Vieider, Philipp Wichardt, and seminar participants at Universität Hamburg, the Southern Risk and Insurance Association annual meeting, and the American Risk and Insurance Association annual meeting. All remaining errors are ours.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaspersen, J.G., Ragin, M.A. & Sydnor, J.R. Linking subjective and incentivized risk attitudes: The importance of losses. J Risk Uncertain 60, 187–206 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-020-09327-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-020-09327-4